This sample Social Cognition Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

People frequently evaluate others and themselves. They judge others when they choose friends, hire babysitters, write employment references, serve as jurors, and select potential mates. Social cognition is the study of how people come to know themselves, other people, and their social world. Social cognition researchers use systematic research to study how people make decisions and evaluations about themselves and others. Researchers study how people attend to, interpret, and recall information about their social world. They determine how the perceiver’s motives, culture, mood, recent thoughts, and attitudes affect judgments and behaviors. They determine how much thought people put in when making judgments and whether conscious thought is necessary for judgments and behaviors.

This chapter briefly explains key social cognition concepts and identifies critical issues, all which are italicized. Pay attention to effects (frequently observed behaviors) and theories (explanations of those behaviors). Researchers identify a reliable human behavior and label it, in order to communicate with other scientists. They then develop explanations (theories) for the findings and test the validity of their explanations.

This chapter first reviews five basic human needs and motivations, to help the reader better understand the research. It then discusses the key issues that interested early social cognition researchers until now. The issues are written as topic headings, with each section briefly discussing classic research, current research, and societal applications. Social cognition researchers studied how people explained other people’s behaviors and formed impressions of others. They studied how cognitive humans are, influences on social judgments, and how humans perceive themselves—all which can be better understood if one considers five basic human needs. Readers wanting a more detailed summary of the area should see Susan Fiske and Shelley Taylor’s (1991) Social Cognition and Gordon Moskowitz’s Social Cognition (2005) textbooks.

Theories

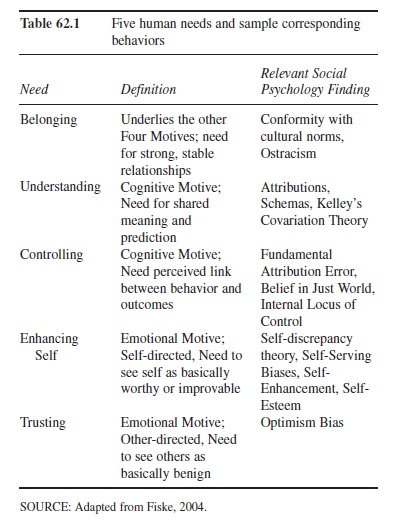

BUC(K)ET Theory: Five Basic Human Needs

Susan Fiske proposed five human needs that motivate behavior: belonging, understanding, controlling, enhancing self, and trusting others. The exact number of needs is still a work in progress. Fiske argued that the five needs assist in making people fit better into groups, thus increasing their chances for survival—a critical goal for humans and animals. Social psychology research supports the idea that people manipulate their perceptions, environment, judgments, and behavior in attempts to fulfill these needs and facilitate survival. The needs and examples of corresponding behaviors are presented in Table 62.1. Fiske argued that the need to belong underlies all the other needs. Humans are social beings who crave connections with others. This need is so strong that people look to others for information and follow the crowd even when they know the crowd is wrong. Social exclusion or ostracism (discussed later) is devastating. Fiske noted that for people to successfully build supportive relationships, they need to understand and control their environment (two cognitive needs) and have self-confidence and trust others (two emotional needs; see Table 62.1). Fiske proposed that all people possess these needs, though the expression of these needs can vary across cultures. Cultures can be described as individualistic (promoting personal independence and achievements) such as the United States, or as collectivistic (promoting group harmony and achievements and personal sacrifice) such as the Latin American and Asian countries. The need to belong to meaningful groups is predicted to be stronger and show itself more readily in collectivistic cultures.

Table 62.1 Five human needs and sample corresponding

Table 62.1 Five human needs and sample corresponding

Attributions: Explaining Others’ Behaviors

An attribution is a cause for a given behavior. Kurt Lewin, grandfather of social psychology, posited field theory—the idea that behaviors can only be understood within the entire field of stimuli. Behaviors are caused by a person’s internal goals, motives, or wishes (internal forces) and the situation (external forces). As a specific motive (hunger) becomes salient, the view of the situation changes and behaviors change. When Sheila is hungry, she notices the local restaurants and does eating-related behaviors.

Restaurant signs are more meaningful to her than laundromat and street signs, once her hunger motive is active. When she is looking for a study partner, she attends to and assesses the intelligence of her peers. Current goals (or needs) affect people’s experiences in the situation.

Fritz Heider argued that people make attributions (causes) for other people’s behaviors. These attributions can be internal (due to dispositions such as personality traits or attitudes) or external (due to forces in the situation). For example, failing an exam (a behavior) can be due to low intelligence (internal attribution) or jackhammering down the hall (an external attribution). In his seminal book, Interpersonal Relations, Heider posed that people have an epistemic need: they need to identify causes of behaviors and to make predictions about other people’s behaviors. Heider argued people are naive scientists who look for causes of behaviors, especially with unexpected or negative events, which disrupt life. People ask “why?” often. (“Why did my roommate yell at me?” “Why did my professor belly dance in class?”) Heider said explaining behaviors makes a predictable, controllable world, which provides comfort. Heider’s ideas were formally tested and supported by later researchers.

Extending Heider’s work, Hal Kelley proposed that behaviors and events can have multiple sufficient causes (any one of them can cause the event). Kelley argued that attributions can be augmented (enhanced) or discounted (minimized). Augmenting takes place when situational factors hinder a behavior, the behavior is done anyway, and perceivers make a stronger personality (internal) attribution. For example, achieving all As in college (behavior) can be explained by saying the student is smart (internal attribution). However, if this student is a single mother of three children and works 40 hours a week (situational factors hindering academic success), perceivers would consider her brilliant (stronger internal attribution). Discounting of an attribution occurs when perceivers learn of other viable causes for the behavior and dismiss the first explanation. Driving a car into a tree (behavior) can be attributed to poor driving skills (internal attribution), but less so if you learn that it was nighttime, there was a thick fog, and the road had an oil slick on it (all situational factors that likely caused the wreck). In sum, the probability of a specific cause is strengthened with augmenting and minimized with discounting.

Two important theories grew from Heider’s work: Jones’s (1990) Theory of Correspondent Inferences and Kelley’s (1972) ANOVA Model. Jones explained forming impressions when observing one behavior. Kelley explained forming impressions when observing several behaviors. Jones and Davis argued in their Theory of Correspondent Inferences that people have a need to find a sufficient reason (not all possible reasons) why the behavior occurred. Their theory identified the conditions in which a personality trait explained the behavior. Their theory is called one of correspondent inferences because they identify the situations in which perceivers believe behavior corresponds (relates) to personality traits. They argued that perceivers examine the consequences (effects) of the behavior to decide whether the behavior was due to one’s trait. Perceivers make trait judgments when the actor knew of the consequences beforehand, had the intention to bring on the consequences, and had capability to bring on the consequences. A 3-year-old who erratically plays with the lights during a theater show is held less accountable than a 30-year-old doing the same behavior. Trait inferences are also more likely when the actor chose to do the behavior, the behavior is rare, the behaviors fulfill the actor’s need, and positive consequences are few. For example, if the only benefit Sara experiences by attending College X is pleasing her parents, people assume that she values her parents’ evaluations of her.

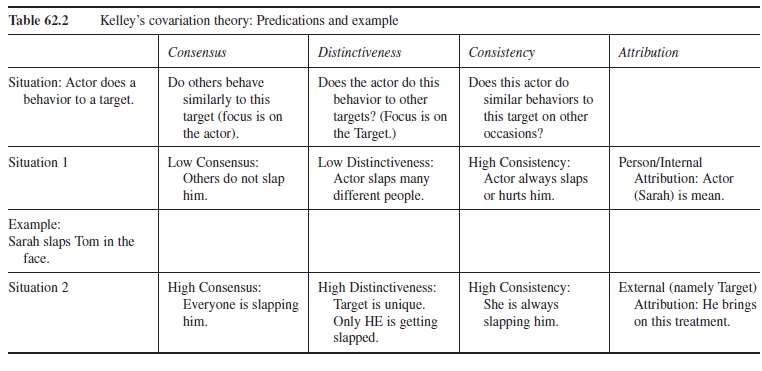

Kelley also proposed that people use the covariation principle to identify causes. The covariation principle states that, for something to be a cause of an effect, the cause must be present when the effect is present and absent when the effect is absent. Kelley argued people are naive scientists, looking for cause-effect relationships. Ron notices that his red sweater gives him hives, yet hives are absent when he does not wear the red sweater.

Kelley’s ANOVA Model explains how people form impressions of others from several behaviors. He argued that people systematically use consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency information to determine the cause of some behavior. For example, to explain why Sarah (the actor) slapped Tom’s (the target’s) face, people need to answer three questions. Consensus: Are other people treating the target this way? Distinctiveness: Has the actor acted this way to other targets? Consistency: Has the actor behaved similarly to this target on other occasions? Notice consensus asks about actors and distinctiveness asks about other targets. The answers are informative: When the answers are “yes” to all three questions, people make a target attribution (Tom brought on the treatment). People make a personal (actor, internal) attribution when consensus is low (Sarah is the only one smacking), distinctiveness is low (actor smacks many different people), and when consistency is high (she is always smacking him). Table 62.2 illustrates Kelley’s theory and its predictions for two situations.

Research shows that people do, in fact, ask these questions when instructed to make these kinds of attributions. Leslie McArthur (1972) presented people with different types of consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness information and found support for the model’s predictions. She also found a tendency for people to use themselves as a standard (“Would I do this behavior?”) instead of using consensus information.

Thus far, Lewin, Heider, Kelley, and Jones argued that perceivers make rational judgments: They search for and use relevant information before making judgments. Research shows perceivers are not this industrious. They search for other information, can possess bad information, and are poor at analyzing diagnostic information when it is presented. When given an information matrix that showed the results when some cause was present and absent, most people without statistical training failed to accurately determine whether a cause-effect relationship was present. See Moskowitz (2005) for more discussion.

People often do not have all the relevant information, so they use mental shortcuts (described as schemas and heuristics). When seeing a behavior, people make the fundamental attribution error, also known as the correspondence bias (Jones, 1990). Both terms describe the finding that people underestimate the power of the situation and readily attribute behaviors to personality traits. If you get in a car wreck, others see you as a poor driver. If you miss a payment, others see you as lazy and irresponsible. This bias occurred even when perceivers knew the actor was forced to do a behavior (e.g., write an essay in favor of Cuban Fidel Castro). Forcing a person to do a behavior is a situational cause for the behavior. The actor’s true attitude toward Castro should still be a mystery. Not so, according to research. Perceivers assumed the author held pro-Castro attitudes, even when perceivers knew the author was forced to write the essay.

Table 62.2 Kelley’s covariation theory: Predications and example

Table 62.2 Kelley’s covariation theory: Predications and example

Lee Ross offered four explanations for the fundamental attribution error: First, perceptually, people blame whatever they are looking at. Observers focus on the actor and his or her behavior and blame his or her personality. Actors are looking at the situation and more readily make situational attributions for their own behaviors. Interestingly, culture directs people’s attention. People from western-individualistic cultures focus on actors, whereas people from eastern-collectivistic cultures focus holistically, attending to the entire field and relations among objects. Second, motivationally, people want to hold others accountable for their actions. Doing so makes the world fair and predictable. Third, culturally, the western-individualistic cultures emphasize taking personal responsibility for one’s actions and that people are ultimately responsible for their actions. In contrast, eastern-collectivistic cultures more readily acknowledge the power of the situation. Supporting this reasoning, research shows that Westerners readily make the fundamental attribution error, whereas Easterners make situational explanations (Morris & Kaiping, 1994). Fourth, the English language promotes trait attributions. It’s easier to say “She’s a helpful person” than to say “she was in a helpful-promoting situation.”

The fundamental attribution error is an immediate judgment, for Westerners. Daniel Gilbert and colleagues have shown that when cognitively busy doing other tasks, Americans automatically (without conscious effort) make trait attributions for behaviors. A fidgety woman is anxious by nature. Moreover, Americans make spontaneous trait inferences, without awareness that such inferences have been formed and without the intention of forming impressions. Correcting one’s judgment by considering situational forces requires controlled (effortful) processing. Automatic versus controlled processing is discussed in detail.

Researchers applied attributions to achievement and clinical settings. Perceivers’ implicit theories (beliefs about causes) of intelligence affect their motivation. Carol Dweck identified people who believe intellectual ability is a stable, fixed trait (entity theorists) and those who believe intellectual ability is malleable and changeable (incremental theorists). Encouraging people to think of ability as changeable was associated with greater persistence when faced with failure. Failure was interpreted as “I need to work harder” to incrementalists, but as “I’m stupid” to entity theorists. Others showed that African American students who viewed intelligence as changeable earned higher grade-point averages than African American students who viewed intelligence as fixed (Aronson, Fried, & Good, 2002). In clinical settings, Martin Seligman has shown that attributional style (how one explains events) affects achievement motivation, health, and depression. Pessimists are people who make internal, stable (unchangeable), and global (affecting all aspects of life) attributions for negative outcomes. For example, if a dinner date appears bored, pessimists conclude they themselves must be uninteresting bores, whereas optimists conclude the dinner companion is temporarily distracted and eager to get to the movie (external, unstable, and specific attributions for negative outcomes). Seligman found that, compared to pessimists, optimists have better achievement, less depression, and better health later in life (Duckworth, Steen, & Seligman, 2005).

Attributions about our own successes and failures affect our behaviors. If Kim enjoys a behavior (e.g., playing tennis or a musical instrument), she has intrinsic motivation (an inside reason) for doing the behavior. When given an additional external reason (money) for doing the behavior, she assumes money enticed her to do the behavior (extrinsic motivation). The overjustification effect occurs when people feel they are being bribed (externally forced) to do a behavior, they no longer enjoy it, and they no longer engage in the behavior. Research shows that children who were paid to play with enjoyable markers no longer enjoyed them or played with them, compared to nonpaid children.

Forming Impressions of Others

Some personality traits go together. Once people infer a person has one trait, they often infer that he or she has many other traits. People have implicit personality theories or beliefs about personalities. Overweight people are assumed to be jolly (like Santa Claus) and need comfort, whereas thin people are assumed to be anxious and hyperactive. Solomon Asch found that certain traits are central traits because they relate to other traits and influence subsequent impressions. Has someone described your professor as “warm” or “cold” prior to your meeting him or her? Central traits affect the context for later traits. For example, Asch found that a “very warm person who was industrious, critical, practical, and determined” was seen more positively than a “very cold person who was industrious, critical, practical, and determined,” though the latter four traits were identical.

Many of us possess positive and negative traits. Researchers asked, “How do people combine information to make an overall impression?” Initial studies posed an additive model (people add the traits). Others posed an averaging model. Norman Anderson’s weighted average model (where important traits get more weight) best describes how people form impressions.

Research shows that people’s evaluations are immediate and can be accurate. John Bargh noted that when pictures of objects and faces flashed for just 200 milliseconds (one fifth of a second), people instantly evaluated them as good or bad, before any rational thought. Sometimes first immediate impressions are correct. Researchers videotaped graduate-student teachers, showed thin slices of teaching behaviors to naïve observers, and compared their ratings of the teachers’ confidence, activeness, and warmth to the students’ ratings at the semester’s end. Observers who saw only a two-second clip showed very similar ratings to those of students who experienced the professor all semester (Ambady & Rosenthal, 1993).

First impressions are powerful and difficult to change. Perceivers show the halo effect (seeing one positive trait and inferring a person has other positive traits). Beautiful people are believed to be sociable, smart, fun, and successful. When trying to learn about another person, negative information is weighed more heavily (negativity effect). People expect others to be kind and respectful, illustrating the trusting motive discussed in Table 62.1. Consequently, negative (immoral) behaviors are more diagnostic of personality than are moral behaviors. Immoral actors behave morally and immorally, whereas moral actors only behave morally.

How Cognitive Are We? Schemas, Heuristics, and Automatic Processing

Though the social world is overwhelmed with information, people often lack relevant information (e.g., distinctiveness information) to make informed decisions. Social cognition researchers proposed that people use schemas (mental frameworks that help people organize and use social information) to make social judgments. There are schemas for situations (called scripts), groups of people (called stereotypes), personality types (person schemas), occupations, and the roles people play (role schemas). Schemas contain expectancies, prior knowledge, and beliefs about a topic.

Schemas benefit people. They free attention, organize information, and improve memory. They guide attention (what information gets notice), affect encoding (provide a context for the information), aid retrieval of information, and affect judgments. Schemas have powerful effects. “I’m having a friend for dinner” has very different meanings if the phrase comes from a party host or a cannibal (such as in the movie, Silence of the Lambs). People attend to information consistent with the schema and often ignore information inconsistent with the schema, unless the information is so extreme we cannot help but notice it. Information that captures attention is more likely to be stored in memory. Information that violates expectations (e.g., a belly-dancing professor) is tagged. People attempt to explain it, increasing its chances of being stored. We also unconsciously and automatically apply stereotypes. Though schemas reduce high cognitive load (times when people are expending much mental effort), using schemas can produce errors. People can wrongly use schemas to fill in missing information (e.g., assume every librarian is an introvert). Schemas are also very resistant to change. People show a strong perseverance effect (or belief perseverance): schemas remain unchanged even in the face of contradictory information. When meeting an example that disconfirms a schema (e.g., a belly-dancing professor), people make a special category (or subtype) for the example. Schemas (beliefs) can become reality in a three-step process, known as the self-fulfilling prophecy. First, Person 1 has a belief about Person 2. Second, Person 1 behaves in a manner consistent with the belief. Third, Person 2 behaves consistently with the belief (showing behavioral confirmation of the belief). In a classic study, Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson tested the intelligence of elementary school children in several classes. They randomly selected some students (chose names by chance) and (falsely) told their teachers these students scored very high and would “bloom” academically later in the year. Teachers did not blatantly tell the children which group they were in. Rather, the teachers’ expectancies and behaviors affected the children’s performance. Teachers gave more attention, more challenging tasks, more constructive feedback, and more opportunities to respond to the “chosen” children (Rosenthal, 1994). Children described as “bloomers” showed significantly larger gains on intelligence tests at the end of the year than did children in the control group. People need not be aware of the expectancy. When expectancies were primed (brought to mind) out of Person 1’s awareness, expectancies affected Person 1’s behavior and produced behavioral confirmation in Person 2. In sum, people use schemas with familiar situations and to reduce mental effort, but their use can produce inaccurate perceptions and judgments.

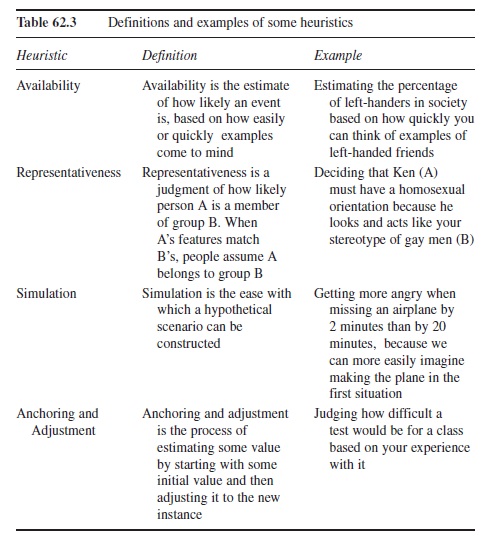

People also reduce cognitive demands by using heuristics (simple rules for making decisions). Heuristics (e.g., looking in the phone book for a phone number) can be accurate most of the time, but the correct answer is not guaranteed when using a heuristic. There are four important heuristics. First, availability heuristic occurs when people judge the likelihood of an event by how easily the event comes to mind (is available in memory). People assume traveling by plane is less safe than by car, given the vivid pictures of airplane crashes in the news, though traveling by plane is safer than by car. Flashy ways of dying (e.g., electrocution, homicides) actually cause fewer deaths than do more mundane causes (e.g., asthma, diabetes), though people assume the reverse. Pairing vivid information increases memory for such information and creates a false impression that they co-occur, called the illusory correlation (seeing a false relationship). This occurs when analyzing large amounts of information. Researchers asked people to learn about majority group and minority group members and their positive and negative behaviors. Both actor groups did an equal proportion of negative behaviors, but perceivers wrongly assumed minority members did more negative behaviors. Seeing a negative behavior from a minority group member (two unusual events) was especially memorable and produced the illusory correlation that they frequently co-occur.

Table 62.3 Definitions and examples of some heuristics

Table 62.3 Definitions and examples of some heuristics

Second, the representative heuristic occurs when people ignore statistical base rates and claim a given example fits a category when its features match the category (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Suppose you went to a party with 100 people, of which 30 were librarians and 70 were engineers. You meet Kim, who is quiet and likes to read books. Do you think Kim is a librarian or an engineer? Statistically speaking, Kim is more likely to be an engineer, though most people are swayed by her features and classify her as a librarian.

Third, the simulation heuristic is a type of availability heuristic, where if people can easily picture (simulate) an event happening, people more readily assume it could have happened. People are angrier when missing a bus by 2 minutes than by 20 minutes because they can picture making the bus if only one or two events had not happened. Counterfactual thinking is the thought process when people imagine alternative courses of actions and outcomes (“What if I had attended a different college, asked him or her out, not purchased that expensive item?” etc.). Simulation and counterfactual thinking affects emotions, causal attributions, impressions, and expectations.

Finally, the anchoring and adjustment heuristic is the tendency for people to “anchor” (or begin with a specific value) and slowly move from there. People can make inaccurate judgments when their anchor is too high or too low and they have not adjusted enough (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Buying cars (or other expensive items) can involve sales people showing customers extremely high prices, in hopes of raising the buyers’ expectations (anchors). Frequently, people use their own personal experiences and standards as an anchor to judge other people’s behaviors, even if they know their experiences are unique (Gilovich, Medvec, & Savitsky, 2000). Both anchoring and adjustment and belief perseverance show that people are reluctant to revise their initial beliefs.

Early researchers described human thinkers as cognitive misers, saying people were cognitively limited: They use mental shortcuts whenever they can. Susan Fiske and Shelley Taylor now describe perceivers as motivated tacticians, fully engaged thinkers with multiple processing strategies available who choose strategies based on goals, motives, and needs. These four heuristics are defined and described in Table 62.3.

Humans engage in rationale, effortful thought when invested in the issue (when the issue affects them personally). If a college proposes arguments explaining why seniors must pass a comprehensive exam to graduate, college students will more carefully consider the merits of the arguments than will noncollege students. Personality traits also predict effortful thinking. People with a high need (desire) for cognition, such as college professors, enjoy analyzing, discussing, and solving complex problems (Cacioppo, Petty, Feinstein, & Jarvis, 1996). People with a low need for cognition do not enjoy and avoid complex thinking. Also, people with an extremely high personal need for structure do not like situations that are uncertain. They overly rely on shortcuts such as prior expectations, stereotypes, and trait attributions when judging others.

Scientists have also studied the extent to which a given behavioral process reflects automatic or controlled processing. Automatic processing is involuntary, unintentional, outside of conscious awareness, and relatively effortless, whereas controlled processing requires conscious and intentional attention, elaboration, and expending effort to process social information. Well-developed schemas and behaviors are often automatically used. People undergo controlled processing when learning a new skill, processing complex information, or processing information in which they have ambivalent attitudes. Recent research shows that the brain structure amygdala is activated with automatic responding (making good/bad judgments), whereas the prefrontal cortex is involved in controlled processing. Several dual-process models propose that humans have both a cognitive system, which is rational, deliberative, and conscious, and an experiential system, which is affective, automatic, and unconscious.

Influences on Social Judgments

Values, beliefs, culture, and experiences affect interpretations and judgments (Ross & Ward, 1996). Naïve realism is naively believing that our own perceptions of the world are accurate reflections of the objective facts. People believe their interpretations of the world are objective, yet they are unaware of this bias. Naïve realism causes several important effects. First, the false consensus effect is the false assumption that most other people share our attitudes, views, and opinions. Lee Ross and colleagues asked undergraduates to wear an embarrassing sign, “REPENT.” Those agreeing to wear the sign said 64 percent of other students would do the same. Those refusing to wear the sign said 77 percent of other students would also refuse. Clearly, the majority of people asked cannot both wear it and also refuse. Second, highly opinionated groups react negatively when reading a story that contains both sides of the issue. Pro-Israeli and pro-Arab perceivers saw a news story that equally represented both opinions when covering a 1982 civilian massacre. Both groups saw the media as biased against their side, called the hostile media effect (Vallone, Ross, & Lepper, 1985). Third, two opinionated groups who read the same controversial article (on capital punishment) with mixed conclusions accepted attitude-consistent information and refuted opposing information (showing belief perseverance). They also developed more polarized (extreme) attitudes, rather than coming together (Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979). Fourth, perceivers overestimate the divide or gap that separates them and their opposition (called the perceptual divide). They wrongly assumed their opposition had more extreme attitudes than their opponents actually did. These inaccurate perceptions facilitate inter-group hostility. See Moskowitz (2005) and Ross and Ward (1996) for more discussion on the perils of naïve realism.

Moods (mild emotions) can also affect processing, judgments, and memory. People who are aroused or in a good mood tend to simplify the situation, compared to when in neutral or negative moods. Experienced interviewers evaluate interviewees more favorably when in a positive mood. Moods affect encoding. People notice and remember information that is consistent with their current mood (called mood-congruence effects). In addition, mood-dependent memory is showing better memory when recalling information in a mood that matched the mood at learning. One’s mood serves as a retrieval cue for information. Both mood at the time of learning and the information are stored in memory.

Perceiving Ourselves

William James (1842-1910), founder of American psychology, was the first to discuss two pieces of the self-concept. He argued that people have beliefs about who they are (the self-concept) and self-awareness (they think about themselves and how they relate to the world). Much social cognition research focuses on self-processes. How do people develop self-concepts? How does living in a collectivistic (or individualistic) culture affect one’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior? What goals are people striving for? How do people develop self-esteem (self-worth)? How do people make judgments and decisions about themselves? How do they manage their presentation to others? Scientists have initial answers to these questions.

Social psychologists identified at least three ways in which adults develop their self-concepts. First, people compare their abilities and opinions with others’. Leon Festinger’s Social Comparison Theory proposes that people have a need/motive to understand how their abilities and opinions “measure up” to those of others. Comparisons with similar others are most informative. Second, people internalize reflected appraisals (others’ opinions) into the self-concept. Others’ self-fulfilling prophecies can become reality when people have weakly held self-beliefs, but not when people have firmly established self-beliefs. William Swann showed that once self-beliefs are held with confidence, people show a self-verification motive. They create situations, in attempts to hear feedback that confirms their self-views (Swann, Rentfrow, & Guinn, 2003). Third, people act like observers who watch their behaviors and infer attitudes, according to Daryl Bem’s self-perception theory. The behaviors and roles people play create their identities. For example, after finishing eating, Joshua claims, “I guess I really was hungry. I ate all the spaghetti.” Reflecting on his behavior, Brad says, “I’m a student, basketball player, pianist, worker, and counselor to friends.” People’s descriptions of their self-concepts change when the context changes. If you ask Jody to describe herself when she’s in a different country, her American status becomes salient, and “American” is likely to be her first response.

Why do human adults have such complex self-concepts? Roy Baumeister (1998) argues that the self-concept serves three functions. These functions are consistent with the motives in Table 62.1. The self has an organizational function: The self-concept is a complex schema that helps us interpret and recall information about ourselves to the social world. Culture affects the content of one’s self-concept and the emphasis placed on personal achievements (Markus, Kitayama, & Heiman, 1996). Westerners (individualists) define themselves separately from others and describe themselves by their personality traits, hobbies, and achievements. They have an independent view of the self. In contrast, Asian, Latino, and other non-western cultures have an interdependent view of the self. They define themselves by the connections they have with their familial, religious, or other social groups (e.g., member of the Inman family, mother, Christian, part of the Hope College community).

The self also has an emotional function, helping people to determine their emotional responses and enhance the self (see Fiske’s third motive in Table 62.1). Failures with one’s self-concept are related to specific emotions. According to E. Tory Higgins’s self-discrepancy theory, people have self-guides (ideal and ought-standards for themselves) that motivate behavior. Higgins found people strive to achieve success and experience depression if they fail to meet their ideal standards. They also avoid failure and experience anxiety with when they fail to meet their ought-standards. Regulating one’s behavior (self-control) takes mental effort, and humans have a limited capacity for self-regulation. People are poor at controlling their behaviors after controlling an earlier behavior. When ostracized (socially excluded), the belongingness need was undermined, self-regulation processes started, and people were less helpful and more hostile to others (Blackhart, Baumeister, & Twenge, 2006).

Human adults strive to create and maintain high self-esteem. Nondepressed adults show several self-serving biases (viewing oneself in a positive light). These biases bolster self-esteem. Research on Abe Tesser’s (1988) self-evaluation maintenance model showed another person’s stellar performance can threaten the perceiver’s self-esteem in domains the perceiver cares about. Tesser found that when people cared about winning, they minimally helped others succeed. When they did help, they helped strangers more than friends. Continually seeing a close friend excel in a cherished domain is painful. People tried to create downward social comparisons (comparisons in which a person excels compared to others). Downward comparisons boost self-esteem. In situations that are less valued, people helped friends more than strangers, emphasized that friendship, and basked in their friend’s glory (boosting personal esteem by affiliating with successful others). Sports fans wear their team’s shirts after victories but not after failures. Affiliating with successful others makes people feel good about themselves.

Consider these other ways to boost self-esteem. Many people have a belief in a just world (a belief that good things happen to good people and bad events were caused by poor human decisions). A strong belief in a just world is related to blaming rape victims, hurricane victims, and AIDS victims, by believing the victims directly and/or indirectly brought the harm on themselves. This belief system creates a sense of security: People believe they can prevent bad outcomes by avoiding those behaviors, which creates a predictable and controllable world. Understanding and control needs are fulfilled. Similarly, many studies supporting terror management theory showed that when the self is threatened (thinking about one’s death), people reduce their anxiety by enhancing their comforting beliefs or derogating threatening ones (Solomon, Greenberg, & Pyszczynski, 2004). People also show the optimism bias, claiming that compared to others, they personally are more likely to experience good outcomes and less likely to experience bad outcomes. Overconfidence is seen in eyewitness testimony; people are often confident about their accurate and inaccurate judgments. People overconfidently predict they will finish more work in a given amount of time than they actual do. Such optimistic perceptions serve to motivate behaviors and give confidence in challenging and threatening situations. Confidence helps you continue studying, but it can lead to dangerous situations. Hopefully, it won’t lead you to try to outrun an oncoming semitruck on a snowy night!

The third function of the self-concept is to regulate behaviors. People strategically create situations to show their likability and competence (two assets for joining a group and increasing one’s survival; Fiske, 2004). Humans strive for Self-efficacy, a sense that one is competent and effective. Some people regulate their behavior more than others. Self-monitoring is a personality variable that identifies who will regulate their behavior more (Snyder, 1980). The behavior of high self-monitors is driven by the situation. High self-monitors typically respond that they are good at playing charades, persuading others, and entertaining people at parties. In contrast, low self-monitors’ behaviors are guided by their internal attitudes and values. They have difficulty persuading others on issues they don’t endorse, playing charades, and changing their behavior across situations. Self-handicapping is also a tactic used more readily in some situations and by certain people to make themselves look good. Self-handicapping is making excuses for failure before the behavior occurs, so a failure is readily attributed to the excuse, not the actor’s lack of intelligence. Procrastination and drinking alcohol prior to a deadline are two common self-handicapping strategies. Self-monitoring and self-handicapping are two behavioral tools that people use to create their desired impression.

Finally, conscious and unconscious thoughts affect behavior. Implicit theories (beliefs) about behaviors affect perceptions of control and behaviors. People have a desire for a controllable world (need 3 in Table 62.1), such that they perceive they have control in situations that lack control (e.g., games of chance). Magical thinking fulfills the need for a predictable and controllable world. People’s beliefs about the locus (source) of control affect their motivation. People with an internal locus of control believe that they actively make events happen in their world. People with an external locus of control believe that outcomes occur randomly, independent of behavioral efforts. People with an internal locus of control more readily attempt challenging tasks after failures (Dweck, 1996).

People also act in ways that are consistent with their unconscious thoughts. Humans show ideomotor action or movement upon the mere thought of it (termed by William James). Unconsciously exposing people to the stereotype of the elderly (e.g., Florida, wrinkle, wise, old) led to slower walking speeds than when not exposed to the stereotype (Bargh & Barndollar, 1996). Thinking about a smart person (professor) led people to perform better on an intelligence test. Thinking about stupidity led to poor performance (Dijksterhuis & van Knippenberg, 1998). Trying to suppress a thought causes the rebound effect (people think of the forbidden thought more than when not suppressing it). Daniel Wegner explained this ironic process of mental control: Thought suppression requires mental effort. Finding the taboo topic is an easy, automatic process for human brains. Not thinking about the thought requires effort. Behavior follows thoughts too. People told not to move a pendulum along the X-axis moved it more along the X-axis than along the Y-axis (Wegner, Ansfield, & Pilloff, 1998). Behavior follows thoughts, even when thoughts are unconscious.

Methods

Social cognition researchers conduct experiments where they manipulate the causal variable (e.g., schema) and examine behavior (e.g., memory). Stimuli can be presented on a computer, by questionnaire, or by participating in a contrived interaction. When studying unconscious influences, researchers present stimuli on computer screens for fractions of a second (e.g., 250 milliseconds). They might create multiple tasks to manipulate cognitive load to examine automatic versus controlled processing. Researchers also use questionnaires to assess relationships between unmanipulated variables (e.g., the participant’s personality trait) and behaviors. Researchers sometimes borrow and extend theory and methods from cognitive psychology (e.g., schema theory).

Applications

Social cognition research has been used to enhance achievement motivation (Dweck, 1996) and minimize the harmful performance effects due to negative stereotyping (Aronson et al., 2002). These researchers have educated the public and clinicians about suppressed thoughts and thought intrusions (Wegner et al., 1998), the limits of self-control (Baumeister, 1998), and the benefits of making mastery-oriented attributions (Duckworth et al., 2005). Social cognition theories have been instrumental in developing treatments for victims with post-traumatic stress disorder (Dan Wegner’s work) and cognitive-behavioral-based major depression (Seligman’s work).

Comparison

Some of these thought processes apply across cultures. Recall that the type of culture (individualistic or collectivistic) strongly affects the self-concept, goals, the basis of self-esteem, perceptual biases, and explanations for behaviors. Compared to collectivists, individualists define themselves separately from others, pursue their self-defined goals, develop self-esteem from personal achievements, show several self-serving biases, and readily make trait attributions. Collectivists define themselves by their relationships, pursue goals defined by others, develop self-esteem by the group’s achievements, can show a group-serving bias, and see situational explanations for behaviors. Current research continues to investigate the extent to which western-based psychological theories apply across cultures. Thus far, some theories describe universal human processes (e.g., attributions—looking for causes of behavior); however, cultures differ in their focus (content). Individualists emphasize trait attributions; collectivists emphasize situational attributions (Morris & Kaiping, 1994), but both go through the process of automatically making a judgment and then correcting that judgment if given sufficient time. Fiske’s (2004) argument that all humans possess the five BUCKET motives, though the motives’ expression varies cross-culturally, has received initial support.

Summary

Social cognition researchers study how thoughts affect emotions and behaviors. They inform society of these processes and offer solutions to societal problems. Researchers have made impressive contributions, given the infancy of the field. Much of the experimentation began in the early 1980s, after the cognitive revolution. We have seen the powers and perils of social thinking. As social animals, humans strive to make sense of their world, share those perceptions with others, and create relationships with others. Thinking can be minimal, biased, or elaborate, depending upon the situational demands and one’s motivations at the moment. Much of human judgment occurs unconsciously or automatically. Bargh (1997) assures us that this is not due to stupidity or laziness, but because such activities are so important that they have come to operate unconsciously. People need not monitor their every breath, nor do they need to monitor their every thought (see Moskowitz, 2005). Much mental thought is best done automatically, so attention can be directed to more complex tasks.

References:

- Ambady, N., & Rosenthal, R. (1993). Half a minute: Predicting teacher evaluations from thin slices of nonverbal behavior and physical attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 431—441.

- Aronson, J., Fried, C., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(2), 113-125.

- Bargh, J. A. (1997). The automaticity of everyday life. In R. S. Wyer, Jr. (Ed.), Advances in social cognition (Vol. 10, pp. 1-62). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Bargh, J. A., & Barndollar, K. (1996). Automaticity in action: The unconscious as repository chronic goals and motives. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to action (pp. 457—i81). New York: Guilford Press.

- Baumeister, R. F. (1998). The self. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 680-740). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Blackhart, G., Baumeister, R., & Twenge, J. (2006). Rejection’s impact on self-defeating, prosocial, antisocial, and self-regulatory behaviors. In K. Vohs & E. Finkel (Eds.), Self and relationships: Connecting intrapersonal and interpersonal processes (pp. 237-253). New York: Guilford Press.

- Cacioppo, J., Petty, R., Feinstein, J., & Jarvis, B. (1996). Dispositional differences in cognitive motivation: The life and times of individuals low versus high in need for cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 197-253.

- Dijksterhuis, A., & van Knippenberg, A. (1998). The relation between person perception and behavior, or how to win a game of Trivial Pursuit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 865-877.

- Duckworth, A., Steen, T., & Seligman, M. (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 629-651.

- Dweck, C. S. (1996). Implicit theories as organizers of goals and behavior. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to action (pp. 69-90). New York: Guilford Press.

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117-140.

- Fiske, S. T. (2004). Social beings: A core motives approach to social psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Gilovich, T., Medvec, V. H., & Savitsky, K. (2000). The spotlight effect in social judgment: An egocentric bias in estimates of the salience of one’s own actions and appearance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 211-222.

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52, 1280-1300.

- Jones, E. E. (1990). Interpersonal perception. New York: W. H. Freeman.

- Kelley, H. H. (1972). Attribution in social interaction. In E. E. Jones, D. Kanouse, H. Kelley, R. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B.Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 1-26). Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press.

- Kunda, Z. (1999). Social cognition: Making sense of people. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 2098-2109.

- Markus, H. R., Kitayama, S., & Heiman, R. J. (1996). Culture and “basic” psychological principles. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 857-913). New York: Guilford Press.

- McArthur, L. A. (1972). The how and what of why: Some determinants and consequences of causal attribution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 22, 171-193.

- Morris, M., & Kaiping, P. (1994). Culture and cause: American and Chinese attributions for social and physical events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 949-971.

- Moskowitz, G. B. (2005). Social cognition: Understanding self and others. New York: Guilford Press.

- Rosenthal, R. (1994). Interpersonal expectancy effects: A 30-year perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 3, 176-179.

- Ross, L., & Ward, A. (1996). Naive realism in everyday life: Implications for social conflict and misunderstanding. In E. Reed, E. Turiel, & T. Brown (Eds.), Values and knowledge (pp. 103-135). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Snyder, M. (1980). The many me’s of the self-monitor. Psychology Today, 13, 33-34, 36, 39-40.

- Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (2004). The cultural animal: Twenty years of terror management theory and research. In J. Greenberg, S. Koole, & T. Pyszczynski (Eds.), Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 13-34). New York: Guilford Press

- Swann, W., Rentfrow, P., & Guinn, J. (2003). Self-verification: The search for coherence. In M. Leary & J. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 367-383). New York: Guilford Press.

- Taylor, S., Peplau, L., & Sears, D. (2000). Social psychology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Tesser, A. (1988). Toward a self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 21, pp. 181-227). Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185, 1124-1131.

- Vallone, R. P., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1985). The hostile media phenomenon: Biased perception and perceptions of media bias in coverage of the Beirut massacre. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 577-585.

- Wegner, D. M., Ansfield, M., & Pilloff, D. (1998). The putt and the pendulum: Ironic effects of the mental control of action. Psychological Science, 9(3), 196-199.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.