This sample Managerial Court Culture Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Court culture as a concept follows from the modern management maxim that there is more than one way to get things done and done well in the workplace. Formulating an effective strategy for a particular workplace requires a good understanding of not only the formal structure and lines of authority but also the unwritten rules, unofficial networks, and underlying norms and behaviors that shape how work is accomplished. As a result, knowledge of an organization’s cultural web is a crucial factor when searching for ways to improve operational effectiveness.

This research paper outlines the development and current state of court managerial culture by reviewing five pertinent inquiries. All of the studies focus primarily on American felony criminal state trial courts and share a comparative The first pair provides initial impetus by popularizing the concept of local legal culture as it relates to why case resolution in some courts is timelier than in others. Timeliness is an undeniable mark of performance due to the US Constitution’s enshrinement of a “speedy trial” in the provisions of the Seventh Amendment. The third study extends the notion of culture by elaborating three distinct work orientations made up of different constellations of norms. The fourth study provides evidence that culture affects different behavior patterns among courts as well as in different attitudes on the part of prosecutors and defense attorneys. The fifth project draws on a broad range of research traditions, including organizational effectiveness in both the private and public sectors and modern methodologies. The inquiry develops a conceptual framework, applies it, and shows how results are solid grounds for changing behavior. The conceptual framework has the dual advantage of creating a typology of culture based on a set of values appropriate to the American context and simultaneously amenable to using alternative values as might exist in other legal systems. Hence, the paper concludes with suggestions for future research, including work in other countries.

Introduction

A perennial theme in contemporary criminal court administration is that better management enables higher organizational performance benefitting all participants in the legal process. Superior administration of the legal process comes about supposedly by the actions of enlightened leaders who cultivate collegial agreement on administrative goals to resolve cases expeditiously and fairly treat litigants and others, and then put objectives into place. Yet, the nature of court organizational structure introduces notable challenges to such aspirations.

Minimal hierarchy of authority exists around which to fashion purposeful management. Professional attorneys, who by virtue of public election or legislative or executive appointment, occupy the position of state constitutional officers. Judges do not select their colleagues and thereby have limited means to control the behavior of their fellow members of the bench. As a result, a call for reaching collective decisions in a court requires an appreciation of the coequal status of judges. Even a judge in a leadership position, such as the presiding or chief judge, possesses limited formal authority to set administrative policy for the court, an equal among firsts. Compare this type of setting to an executive agency led by a chief cabinet officer that appoints assistant secretaries. If the judges are willing to share, collaborate, and follow the lead of a presiding judge, supported by a court administrator, establishing court-wide ways of doing business is a viable option.

On the other hand, if individual judges seek to maintain autonomy in administrative matters, reaching agreement on standard work practices is much more difficult. As a result, voluntary commitment to collective decision making inhibits the adoption of court-wide policies and procedures – even those deemed to be best practices.

Courts are not the only institutions challenged by calls for synchronized management that seem quite natural in the bottom-line motivated private sector. They fit within a category of structures called loosely coupled systems. “In loosely coupled systems, the forces for integration—for worrying about the whole, its identity, its integrity and its future—are often weak compared to forces for specialization” (Hirschorn 1994). Coordination is difficult because the members do not think about system-wide goals, but, as in the case of courts, focus instead on their own subunit, assigned caseload, or courtroom. Recognizing the decentralized character of how decision making occurs in each court is another way of saying court culture matter.

Early Efforts

The first term to describe court culture was local legal culture. The idea of local legal culture arose in two complementary studies of delay reduction in criminal courts during the 1970s. In 1976, Nimmer (1976) observed that the “local discretionary system” is a major obstacle to criminal court reform efforts and later went on to claim that lengthy case processing times are “most directly associated with prevailing informal norms of the judicial process and with the personal motivations of participating attorneys and judges” (1978). Following this pioneering work, what caught the imagination of the field of court administration as well as law professors, judges, and social scientists was a subsequent study of both civil and criminal trial courts by Church et al. (1978): They formulated a working hypothesis that challenged the conventional wisdom that resources determined success in resolving cases expeditiously. They instead postulated

The speed of disposition of civil and criminal litigation in a court cannot be ascribed in any simple sense to the length of its backlog, any more than court size, caseload, or trial rate can explain it. Rather, both quantitative and qualitative data generated in this research strongly suggest both speed and backlog are determined in large part by established expectations, practices, and informal rules of behavior of judges and attorneys. For want of a better term, we have called this cluster of related factors the “local legal culture.”

Similar to Nimmer, Church et al. defined local legal culture as the “established expectations, practices and informal rules of behavior of judges and attorneys.” Their interpretation of the wide variation in the timeliness of different courts attributed the speed of resolution more to the views of judges and attorneys than to structural, resource, or procedural distinctions among courts. Both sets of studies consider expectations stable implying that efforts to reduce court delay encounter strong resistance unless the expectations themselves are the subject of planned change. The concept of local legal culture enjoyed acceptance of the proposition that timely court performance is primarily governed by shared beliefs, expectations, and attitudes, although the substantive nature of the determining views lacked specificity and confirming evidence. As a result, local legal culture does not distinguish different types of cultures and does not offer a basis for putting courts into different categories.

Culture As A Working Hypothesis

Local legal culture is the subject of considerable attention and conceptual enrichment in a third inquiry by Eisenstein, Fleming, and Nardulli (Eisenstein et al. 1987). These scholars studied three criminal courts in each of three states, Illinois, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. They claim norms define how the courts should operate and that differences in norms contribute greatly to the observed variety in how courts conduct business. They extend the previous research by focusing more on what constitute the norms. By calling particular sets of norms “work orientations,” they signal that norms are complex and have multiple consequences.

Work orientations “are rationalizing principles” that court leaders “use to explain why particular tasks or functions” are structured the way they are in their respective courts (Nardulli et al. 1988). These powerful forces are not the same from court to court, but they also are not unique to each court community. Indeed, the scholars see three types of distinctive work orientations in the courts they studied: (1) structural or formal, (2) efficiency, and (3) pragmatic orientations.

The first orientation emphasizes the compliance with professional norms including close adherence to rules and the rejection of expediency. The second orientation places a premium on the efficient use of resources and promotes the expeditious handling of cases, even if the achievement of smooth handling occasionally calls for deviation from rules. Finally, a pragmatic orientation is the most flexible approach because the routine is whatever the consensus is at a specific point in time. With no long-term commitment made to a particular manner of conducting business, the prevailing norm is deemed satisfactory until a problem emerges calling the existing paradigm into serious question. Then, new agreements on ways of resolving cases are necessary and appropriate and the emerging consensus guides the court until it too, ultimately proves problematic. This intriguing configuration of cultures advanced the concept of local legal culture but emerged as a working hypothesis at the conclusion of the inquiry. None of courts under study actually were placed in one of the orientation categories and no tests were conducted on the relationship between orientations and expected consequences.

Judges Nudge Attorneys To An Expeditious Culture

A fourth inquiry by B. Ostrom and Hanson (1999) provides empirical evidence pertinent to a critical aspect of managerial culture. Their study proposed that timeliness and quality are compatible. This proposition challenged the popular view that efforts to resolve cases more quickly compromise quality because delay reduction activities cut corners. This research focused on nine midsized communities: Albuquerque, Austin, Birmingham, Cincinnati, Grand Rapids, Hackensack, Oakland, Portland, and Sacramento. An initial part of the research involved dividing the courts according to their observed degrees of timeliness and placing them into one of three subgroups: very expeditious, moderately expeditious, and least expeditious. To test the study’s hypothesis, frontline attorneys completed questionnaires that tapped into their views on the workings of the state trial court where they practiced and how they assessed the opposing side.

Findings from the investigation revealed that when courts act decisively to manage the litigation, they achieve both timeliness and enable attorneys for both the state and the defendant to prepare and present their arguments effectively. Attorneys have distinctive views toward the leadership role played by a court, a court’s ability to communicate its expectations clearly, the degree to which the opposing side is well trained and prepared for trial, and the extent to which the opposing side operates in an adversarial manner. On the one hand, if attorneys see a court exercising firm leadership, a court stating its policies clearly, and the opposing side is equipped for trial, the court is among the most expeditious subgroup. Conversely, if the attorneys see a court as a hazy communicator, a source of weak leadership, and the opposing side as ill prepared, the court is of lesser expeditiousness. In all three subgroups, attorneys view the opposing side as a strong adversary, suggesting the timely resolution of cases does not require counsel to abandon the goals of protecting society (prosecutor) or to defend a criminal defendant’s constitutional rights (defense attorney). These relationships offer strong evidence that the degree to which the Seventh Amendment is consistent with reality depends on effective management actions taken by judges and administrators and embraced by legal practitioners. However, what is missing concerns the rationale prompting judges to exercise control over the legal process in some courts to a greater degree than in other courts.

Taken together, this previous body of research does converge on the central point that court culture, norms, and beliefs held by judges, attorneys, and court administrators shape how courts operate. Moreover, these investigations document that legal practitioners are aware of court policies to the extent that judges and administrators clearly articulate when, how, and why court proceedings are going to occur. These four studies provide solid justification for further inquiry into the specific norms and values associated with different culture types. A fundamental component missing from the initial research was a methodology for measuring culture and an investigation into the consequences of possible cultural variation.

Constructing Managerial Court Culture

The earlier lines of research primarily affirm what court administrators and judges know: culture plays an important role in how courts function. Some management cultures inhibit modernization, reform, and performance. Others are more conducive to the development and adoption of better ways of doing things. In essence, the notion of local legal culture emerged as a shorthand phrase to refer to a host of norms and resulting behaviors not otherwise easily explained. Unfortunately, simply naming a phenomenon is not the same as measuring it and using it to both explain and improve court performance. Without a vocabulary and set of tools to distinguish fundamental types of cultures, courts will continue to struggle in building a management culture that supports and expects to achieve high-quality case resolution.

Building on and refining previous studies, a fifth approach by Ostrom et al. (2007) provides a more comprehensive framework, along with a set of steps and tools to assess and measure a court’s current and preferred culture. Culture assessment furthers observation and measurement of the abstract concept of court culture, thereby making it an explicit part of court management and reform efforts. Because assessing court culture can yield systematic information compatible with and useful to understanding court performance and the allocation of court resources, an expository summary of this fifth link in a long line of research indicates the current state of knowledge.

- Ostrom et al. follow the lead of managerial experts who contended culture is the glue that operates at many different levels in an organization. Schein (1999) argued that to comprehend what matters in culture, one must strive to understand the espoused values (i.e., the values that shape why an organization acts in a particular way) and basic assumptions (i.e., jointly learned values, beliefs, and assumptions that become shared and taken for granted in an organization) that shape the way work gets done in the organization. For Schein, culture is the mental representation of the work environment that members of the organization carry in their heads.

Schein’s advice, applied by B. Ostrom et al. to the study of courts focused on shared mental models that judges, administrators, and staff hold and take for granted. A court’s management culture manifests itself in what is valued, the norms and expectations, the leadership style, the communication patterns, the procedures and routines, and the definition of success that makes the court unique. More simply: “The way things are done around here.”

- Ostrom et al. accepted the proposition that culture evidences itself in the “accumulated shared learning of a given group” (Schein 2004). For courts, this shared learning comes from parallel experiences in meeting the aims of the judicial branch. The live and unanswered question then became for B. Ostrom et al. as, if a court’s culture is the result of accumulated learning, how does one describe and catalogue the content of that learning?

Types of Managerial Court Culture. The conceptual framework developed by B. Ostrom et al. organized managerial culture into four distinct types of cultures, communal, networked, autonomous, and hierarchical, defined as follows:

- Communal: Judges and managers emphasize the importance of getting along and acting collectively. Communal courts emphasize group involvement that produces mutually arrived at agreements. Procedures are open to interpretation and creativity is encouraged when it seems important to “do the right thing.”

- Networked: Judges and managers emphasize inclusion and coordination to establish a collaborative work environment and effective court-wide communication. Efforts to build consensus on court policies and practices extend to involving other justice system partners, groups in the community, and ideas emerging in society. Judicial expectations concerning the timing of key procedural events are developed and implemented through policy guidelines built on the deliberate involvement and consensus of the entire bench. Court leaders speak of courts being accountable for their performance and the outcomes they achieve.

- Autonomous: Judges and managers emphasize the importance of allowing each judge wide discretion to conduct business. Many judges in this type of court are most comfortable with the traditional adversary model of dispute resolution. Under this traditional approach, the judge is a relatively passive party who essentially referees investigations carried out by attorneys. Individual judges exercise latitude on key procedures and policies. Limited discussion and agreement exist on court-wide performance criteria and goals.

- Hierarchical: Judges and managers emphasize the importance of established rules and procedures to meet clearly stated court-wide objectives. These courts seek to achieve the advantages of order and efficiency in a world of limited resources and calls for increased accountability. Effective leaders are good coordinators and organizers. Recognized routines and timely information reduce uncertainty, confusion, and conflict in how judges and court staff make decisions. Empirical Findings. B. Ostrom et al. measured the extent that courts in the real world fit into one of these four types. Moreover, they assessed both the current culture and the type of culture that judges and administrators preferred to see in place in the future. Additionally, both prosecutors and public defenders provided evaluations of the performance of the court where they practiced on a daily basis. As a result, conclusions surfaced on what, if any, consequences flowed from the judicial embrace of a particular culture. The following synopsis highlights their essential observations.

Courts with hierarchical cultures achieve objective standards of timeliness promoted by the American Bar Association (ABA) and other groups, more closely than courts with other dominant cultures do. Interestingly, all of the courts under study exhibited awareness of this connection. Every court, according to the preferences of judges and administrators, seeks to increase its hierarchical culture in the area of case management. This common desire likely arises because none of the courts currently meet the ABA-prescribed time frames. Courts are cognizant of this situation and seek to do better by moving toward a culture more conducive to expedition and timeliness.

Like culture, court performance has multiple dimensions. Moving beyond timeliness, practicing attorneys evaluate courts on how well they achieve other important goals, such as access, fairness, and managerial effectiveness. With these criteria, the picture becomes more complex. The courts with more hierarchical cultures rated less satisfactorily on access and fairness, for example, than courts with other cultures. Prosecutors and public defenders do not see only virtue in a court’s emphasis on timeliness and a move toward a more hierarchical culture to achieve that goal. Both sets of attorneys also can see greater benefits to themselves from the courtroom workgroup relations fostered by an autonomous culture’s minimal emphasis on solidarity. Vested interests in established work patterns perhaps lead attorneys to view courts with autonomous cultures as also doing better when it comes to access, fairness, and managerial effectiveness. Further complexity arises because prosecutors and public defenders disagreed over the relative merits and limitations of other cultures. The former see the greatest advantage in networked cultures because of the emphasis by the court on guidelines consistent with a prosecutor’s desire for some firmness in guilty plea policies. Public defenders have an opposite orientation and like a communal culture’s emphasis on flexibility that they view as enhancing their role in gaining the best resolution for their clients. Managing the competing interests of prosecutors and public defenders, while maintaining an effective internal work environment for judges and court staff members, highlights the management challenges facing court leaders.

Methodology. The development of this fourfold typology follows from an analysis of how expert practitioners believe core values affect and relate to carrying out work. Sixteen values culled from the literature on court administration include such distinct values as collegiality, continuity with the past, discretion, standard operating procedures, flexibility, ruleoriented, innovation, judicial consensus, and self-managing. Using a tightly structured questionnaire, 53 seasoned practitioners, including judges, administrators, prosecutors, and defense attorneys, compared and contrasted the values. This exercise asked the practitioners to indicate how closely each of the 16 values relates to each of the other 15 values. The results of paired comparisons, using the technique of multidimensional scaling, showed four clusters of four values each.

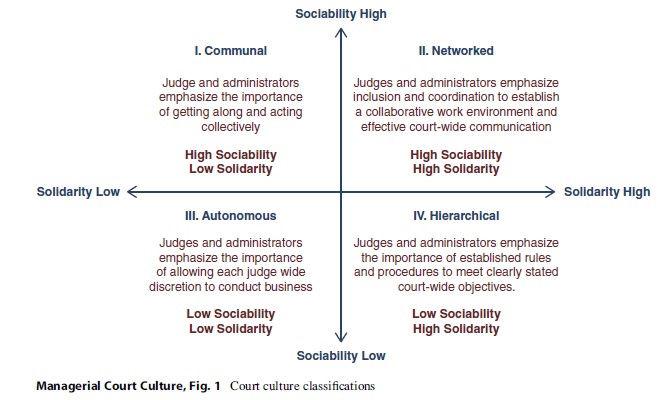

The clusters illustrate the core values of different types of cultures and fit along two dimensions called solidarity and sociability. Solidarity refers to the degree to which a court has clearly understood shared goals, mutual interests, and common tasks and sociability refers to the degree to which people work together and cooperate in a cordial fashion. Each of the four cultures is a particular combination of solidarity and sociability, as shown in Fig. 1.

Communal culture is low on solidarity and high on sociability. Its distinctive values are flexibility, egalitarianism, negotiation, and trust. A network culture seeks both sociability and solidarity. Its values include judicial consensus, innovation, visionary thinking, and human development. An autonomous culture emphasizes neither sociability nor solidarity. Its values are self-managing, continuity, independence, and personal loyalty. A hierarchical culture stresses solidarity but not sociability. Its values are rules, modern administration, standard operating procedures, and merit-based staff promotions.

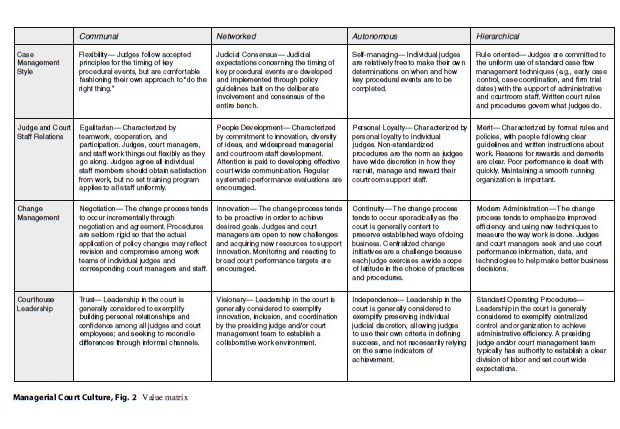

- Ostrom et al.’s proposed concept of culture is manifested in familiar and recognizable activities called “work areas,” such as the handling of cases, the responsiveness of courts to the concerns of the community, the division of labor and allocation of authority between judges and court staff members, and the manner in which court leadership is exercised. Each particular culture’s way of doing things exists in four work areas as seen in the Value Matrix (Fig. 2).

- Ostrom et al. developed a survey instrument to determine what individual judges and administrators believed about the execution of work in key areas. Because each culture was presumed to manifest itself differently, the instrument asks individuals to indicate how closely each of four ways of getting work done corresponds to what happens in their court (current culture) and what they would like to see as the work style in the future (preferred culture). An application of the framework to courts in California, Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Minnesota, Ohio, Oregon, Utah, and Washington and the Tax Court of Canada found examples of each of the four cultures, although the autonomous culture is the most frequent. This balanced distribution suggested courts are not monochromatic in their work orientations. On the other hand, regardless of the current culture, the vast majority of courts under study indicated a similar mosaic-like preference for the future. Specifically, they tend to desire hierarchical orientations to dominate in the work areas of case management and change management, networked orientations to dominate judge–staff member relations, and a communal culture to dominate the area of courthouse leadership.

Origins and Controversy. The effort to study managerial court culture has roots in initial court research and from private sector studies and selected public organizational experts on culture. Concerning private sector management and performance, B. Ostrom et al. looked to the work of business school scholar Robert Quinn and his colleagues. They had embarked on nearly two decades of sequential studies and made clear the relevance of culture as they summarize the traits of successful private sector businesses:

The major distinguishing feature in these companies, their most important competitive advantage, and the most powerful factor they all highlight, as a key ingredient in their success, is their organizational culture. The sustained success of these firms has had less to do with market forces than company values; less to do with competitive positioning than personal beliefs; less to do with resource advantages than vision. In fact, it is difficult to name even a single highly successful company…that does not have a distinctive, readily identifiable, organizational culture. (Cameron and Quinn 1999)

Growing awareness that culture matters to performance and long-term success in the world of business triggered the emergence of culture analysis as a definable area in the field of management and organizational studies largely beginning in the 1980s.

- Ostrom et al. then found support in applying Quinn’s ideas to courts in the views of public sector scholars, such as Wilson and Dilulio. Wilson (1989) had made the case for including organizational culture in the study of public sector organizations. Wilson opened the door for integrating work on private sector organizational culture into the study of the public sector with the following claim: “Organizations matter, even in government agencies” (1989). He argued culture is a core topic for public sector organizational analysis because organizations have a culture just as an individual has a personality. Organizational culture is a relevant and important facet of all bureaucracies – public and private.

However, when shifting the focus to public institutions, Wilson anticipated some difficulties in diagnosing a public organization’s culture. Specifically, public organizations do not necessarily have a single culture. In response, B. Ostrom et al. expected courts might manifest a mosaic of complementary and competing cultures. Identifying and understanding the resulting mosaic and the relationship to performance becomes vital to public sector management.

Additional insights come from DiIulio (1993) who had suggested that the measurement of organizational culture is an important part of any public administration improvement strategy. He had proposed the following agenda for doing so:

- To observe how members at every level of an organization “really behave”

- To relate systematically these observations to the formal character of the organization in order to see what (if any) connections exist

- To search systematically for the connections (if any) between organizational activities and real-world outcomes

The key research focus is to discover the relationship between “the way things are” in an organization and the ability of the organization to reach its stated ends.

Following the direction of Wilson and DiIulio’s arguments, B. Ostrom et al. found three reasons to suggest private sector studies inform the specific topic of court culture. First, the concept of court culture and the parallel private sector investigations both revolve around the idea that “the way things get done” (i.e., work orientations) defines the character of the organizations. To the extent that judges and administrators in one court have particular views on how cases should be resolved, they will organize themselves differently than individuals with dissimilar views in another court. Second, work orientations shape the degree of a court’s effectiveness. This linkage in the private sector made the search for a parallel relationship in public institutions, including courts, worthwhile. Third, business school scholars have shown private organizational culture is susceptible to measurement and the results are interpretable within a typology of cultures.

Of course, some scholars argue that knowledge about private organizations cannot be a basis for understanding public bodies. Wallace Sayre expressed this viewpoint in his well-known assertion that public and private organizations are “fundamentally alike in all unimportant respects.” More specific assumptions underlying this argument are public agencies that, in contrast to private bodies, lack a clear bottom line (e.g., profit and market performance), have a diverse set of goals and performance criteria, and are more “open” and with greater exposure to public scrutiny, and managers of public organizations have shorter time horizons. Yet, when looking at the temperaments, skills, and techniques of judges, court managers, and court employees, the differences between public sector and private sector organizations and management are minimal. This point of view is expressed in Lynn’s observation that

[t]he two sectors are constituted to serve different kinds of societal interests, and distinctive kinds of skills and values are appropriate to serving these different interests. The distinctions may be blurred or absent, however, when analyzing particular managerial responsibilities, functions, and tasks in a particular organizations. The implication of this argument is that lesson drawing and knowledge transfer across sectors is likely to be useful and should never be rejected on ideological grounds. (2003, 3)

The ability to measure culture by borrowing the tools available in the broader organizational culture literature highlights the relevance of the methodologies to the field of court administration.

Unsettled Issues

An unresolved issue concerns the scope of the managerial court culture approach. Even in the strictly American context, the question is whether a culture framework applies to different types of disputes, such as civil, family, juvenile, or probate. For B. Ostrom et al., broadening the scope of study beyond criminal cases is possible because despite the unique set of substantive laws governing other types of disputes, they all share an essential characteristic. In every court, cases move from one key procedural event to another. To execute this common process, the activities represented by the four areas of the court culture framework occur in every type of case. As a result, case management style happens in civil cases just as in criminal cases. Judge–staff relations exist in probate cases just as in criminal cases. Courthouse leadership governs juvenile cases just as in criminal cases. Furthermore, how the work is to be done in each area reflects cultural values such as independence, discretion, inclusiveness, and efficiency more than by differences in evidentiary standards, rights of the parties, and severity and type of possible sanctions imposed on a losing party among courts.

Legal criteria specify desirable goals more than how to achieve them. In fact, appellate courts are likely to be amenable to cultural examination because the key procedural events are more definable and similar across appellate courts than trial courts (Chapper and Hanson 1990). Experts and practitioners are likely to have multiple hunches and notions to explain anticipated cultural variation. What judges and court administrators think are appropriate work orientations will likely vary by case type and differ from what criminal courts demonstrated. For example, in the area of case management style, judges with a civil docket may prefer to give greater deference to the bar. In the area of judge–staff relations, probate judges may want to grant greater independence to legally trained staff. In the area of courthouse leadership, judges handling juvenile dependency cases may seek to develop strong connections with social welfare agencies. For all these reasons, B. Ostrom et al. believe that despite variation in work orientations across areas of law, the managerial court culture framework opens up a valuable vista to future court studies.

Ongoing efforts to understand and diagnose court organization culture in American trial courts highlight the relevance of the approach to legal systems outside the borders of the United States. Without claiming that the use of those tools answers all questions, court scholars in other countries should benefit by adapting what has been set in motion. Applicability of the methods likely hinges on three conditions: (1) the opportunity for collegial discussion among judges and staff members exists, (2) judges and staff members have some say over the design and implementation of court administration policies and practices, and (3) the judge with official leadership responsibilities has an interest in organizational improvement. The more vibrant the collegial discussion, the more aware judges are that their administrative decisions have independent consequences, and the greater the interest of administrative leaders, the greater the utility of investigating managerial court culture. The use of the same methods that are free and open to inspection augurs well for truly comparative research across boundaries.

Conclusion

Culture focuses attention on variables exercising a strong, independent influence on the administration of the legal process. Reforms need to bond with cultural values to stand a chance of influencing court performance. For this reason, the effort to understand cultural values as indicators of the current state of affairs and future possibilities is as deserving of attention as any other aspect of court management, such as structure, process, or resources. Implementation of new practices becomes less difficult under a supportive culture.

Bibliography:

- Cameron KS, Quinn RE (1999) Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: based upon the competing values framework. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA

- Chapper JA, Hanson RA (1990) Intermediate appellate courts: improving case processing. National Center for State Courts, Williamsburg, VA

- Church TW Jr (1982) The ‘old’ and the ‘new’ conventional wisdom. Justice Syst J 8:712

- Church TW Jr, Carlson A, Lee J-LQ, Tan T (1978) Justice delayed: the pace of litigation in urban trial courts. National Center for State Courts, Williamsburg, VA

- DiIulio JJ Jr (1993) Measuring performance when there is no bottom line. In: Performance measures for the criminal justice system. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC,pp 143–156

- Eisenstein J, Jacob H (1977) Felony justice: an organizational analysis of criminal courts. Little Brown, Boston

- Eisenstein J, Fleming R, Nardulli P (1987) The contours of justice: communities and their courts. Little and Brown, Boston

- Feeley M (1983) Court reform on trial: why simple solutions fail. Basic Books, New York

- Fleming R, Nardulli P, Eisenstein J (1992) The craft of justice. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA

- Friesen EC, Gallas EC, Gallas NM (1971) Managing the courts. Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis

- Goffee R, Jones G (1998) The character of a corporation. Harper Business, New York

- Hirschorn L (1994) Leading and planning in loosely coupled systems. CFAR, Cambridge, MA

- Lipsky M (1976) Street level bureaucracy. Russell Sage, New York

- Lynn L Jr (2003) Public Management. In: Handbook of Public Administration. Sage, London

- Nardulli PF, Eisenstein J, Fleming RB (1988) The tenor of justice: criminal courts and the guilty plea process. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL

- Nimmer R (1976) A slightly moveable object: a case study in judicial reform in the criminal justice process: the omnibus hearing. Denver Law J 48:206

- Nimmer R (1978) The nature of system change: reform impact in criminal courts. American Bar Foundation, Chicago, IL

- Ostrom BJ, Hanson RA (1999) Efficiency, timeliness, and quality. National Center for State Courts, Williamsburg, VA

- Ostrom BJ, Hanson R (2010) Understanding and diagnosing court culture. Court Rev 45:104–109

- Ostrom BJ, Hall DJ, Schauffler RY, Kauder N (2005) CourTools. National Center for State Courts, Williamsburg, VA

- Ostrom BJ, Ostrom CW, Hanson RA Jr, Kleiman M (2007) Trial courts as organizations. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA

- Quinn RE (1988) Beyond rational management. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

- Quinn RE, Rohrbaugh J (1983) A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Sci 29(March):363–377

- Schein E (1999) The corporate culture survival guide. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

- Schein E (2004) Organizational culture and leadership, 3rd edn. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

- Trial Court Performance Standards (1997) Trial court performance standards measurement system implementation manual. Bureau of Justice Assistance. U.S. Department of Justice

- Wilson JQ (1989) Bureaucracy. Basic Books, New York

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.