This sample Plea Bargaining Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

As criminal justice systems increase in volume, they turn to negotiated guilty pleas as a primary method to dispose of cases. The prosecution offers reduced sentencing risk to defendants in exchange for more certain and inexpensive convictions. Although such negotiated outcomes are unpopular with the general public, the full-time practitioners who operate the system think of plea bargains as a necessary practice in busy courts. Negotiated guilty pleas have become by far the most common disposition of criminal charges in the United States, and similar practices are becoming more prevalent in other countries. Plea bargains create some uncertainty about the accuracy of convictions in the system and alter the balance of power among criminal justice actors by making judges and juries less influential by comparison to prosecutors. While external legal limits on plea bargains have mostly proven ineffectual, prosecutor offices routinely place internal administrative limits on the use of plea bargains.

Introduction

Criminal defendants in the United States usually decide to plead guilty. Very often, defendants negotiate with the prosecution to receive particular benefits as a precondition to entering a guilty plea – so often, in fact, that these so-called plea bargains have become more common and more important than criminal trials. In the United States, more than 9 out of every 10 felony convictions (and more than 99 out of every 100 misdemeanor convictions) derive from guilty pleas, and the overwhelming majority of guilty pleas occur after the parties negotiate the terms of that plea. Plea negotiations have been slower to arrive in other countries, but criminal court systems around the world often deal with increased volume by allowing some form of discounted sentence in return for a negotiated settlement. Plea bargains, in some form or another, are critical to the operation of high-volume criminal justice systems around the world today.

The dominance of plea bargaining has predictable effects on the institutions of criminal justice in the United States. Most immediately, it makes criminal juries less influential. Negotiated pleas also shift power away from the trial judge toward the parties; they particularly strengthen the hand of the prosecutor. The prosecutor does not merely present legal and factual arguments to the judge on an equal footing with the defense attorney. Instead, the prosecutor hears arguments from the defense and then selects from the available charges and evidence thus substantially impacting the ultimate sentence. The judge, in effect, reviews these prosecutor decisions for possible error in exceptional cases. This shift of power in favor of prosecutors is more pronounced in “guideline sentencing” states that link the sentence more closely to the charge of conviction and to particular factual findings about the crime.

Plea bargaining also affects outcomes in the criminal courts. For one thing, system volume goes up. A system that relies heavily on negotiated pleas can process more cases than a jurisdiction that resolves more of its cases through trials. Negotiated plea bargains also probably trade the quality of convictions for a higher quantity of cases. As systems get busier, the risk of erroneous convictions increases.

External limits on the terms of negotiation between prosecution and defense are available in some systems but are still unusual and have shown only limited practical effects. Internal limits on bargaining practices imposed within the bureaucratic hierarchy of the prosecutor’s office are still the most common limits on individual sentencing discretion of a prosecuting attorney.

This research paper begins with a review of the most common topics for bargaining between the defense attorney and the prosecutor in criminal cases. It then discusses the prevalence and systemic effects of those party negotiations, both domestically and internationally. The paper closes with a review of the external and internal controls that legal systems use to structure prosecutorial discretion.

Topics For Plea Negotiations

During plea negotiations, the prosecution can offer the defendant two categories of benefits in exchange for a plea of guilty. First, under a “sentence bargain,” the prosecutor agrees to recommend to the judge a sentence below the maximum available, without amending the charges. A variation on this type of agreement involves a “fact bargain.” In this situation, the prosecution and defense agree to represent to the court that certain facts were either present or absent in a case. Under the sentencing rules of some jurisdictions, these facts trigger specific sentencing consequences.

The second major category of negotiated plea aims for a “charge bargain.” In this situation, the prosecutor agrees to reduce the most serious charge to some lesser offense or to reduce the total number of counts in the indictment or information. The effect of amending the charges is to reduce the defendant’s potential exposure to more severe sentence outcomes.

Sentence Bargains

The parties develop detailed knowledge about the strength of the evidence, the expectations of the victims, the most likely outcomes of any legal issues presented, and the normal sentences imposed in similar cases. The judge, meanwhile, does not get involved in the details of the case as early as the parties and never becomes as familiar as the parties with the specifics of the crime and the offender’s background. When the court faces a crowded docket and the parties assure the judge that a given sentence is appropriate – particularly if that recommendation falls roughly into a normal range of sentences for this crime – the judge usually accepts the recommendation (Scott and Stuntz 1992).

Sometimes the parties want a level of certainty about the sentencing outcome that is not possible based on sentencing recommendations alone. The criminal procedure rules in some jurisdictions allow the defendant to enter a plea of guilty conditioned on the judge’s acceptance of the agreed-upon sentence. In other words, the defendant may withdraw the plea of guilty if the court later rejects the specified sentence. Some scholars favor sentence bargains that give the judge something more than a “take it or leave it” option; more substantial input for the judge in the selection of the sentence leads, according to this view, to a more balanced sentencing system (Alschuler 1976; Wright and Miller 2002).

Before accepting a plea of guilty, the trial court judge must be convinced that the defendant’s plea is “knowing and voluntary” and that the prosecution holds a sufficient “factual basis” to prove each element of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt. Other facts may be relevant to the sentence, as well, even if they are not elements of the offense. For instance, in the federal system, a defendant who plays a “minimal role” or “minor role” in a group offense receives a lower sentence.

Given this opportunity to control the available sentence through the facts they plan to present, the parties naturally turn to negotiations about the proof of these non-element facts; they agree in some cases to tell the judge that the fact is present or absent from the case. The parties cannot lie to the judge and cannot compel the judge to make the factual finding that forms the basis for their agreement. But the prosecutor and defense attorney do exercise serious practical influence when they present a united front to the judge.

This subtype of sentence bargaining is sometimes known as “fact bargaining.” It is especially pertinent in jurisdictions with sentencing guidelines or other statutes that attach specific sentencing consequences to particular facts.

For instance, some state codes authorize a 5-year increase in a sentence based on the use of a weapon during commission of the crime. The prosecution and defense might negotiate an agreement to stipulate to the judge that no weapon was used during the crime.

The prosecutor sometimes goes beyond the role of advocate and plays a strong gatekeeper role for some non-element facts. In these special situations, the prosecutor does not merely request a factual finding from the judge; instead, the prosecutor herself exercises the power to increase or decrease a sentence automatically. For example, in the federal system (and in some states), the offender is eligible for a sentence discount after cooperating in the government’s investigation of further crimes only if the government certifies that the defendant provided “substantial assistance.” The government’s willingness to file such a motion is one of the important bargaining chips available to the prosecutor. Some states give the prosecutor a similar gatekeeper function over certain sentencing enhancement facts, such as the proximity of a narcotics sale to school grounds or the fact that a defendant’s prior record makes him or her a “habitual felon.” The defense attorney and prosecutor routinely bargain to determine whether the prosecutor will file the allegations that trigger such a sentencing enhancement.

Charge Bargains

Criminal codes in both the federal and state systems give prosecutors a generous menu of options in the selection of charges. Many common fact scenarios could support criminal charges under multiple sections of the criminal code, each leading to different potential sentencing outcomes.

After the initial filing of charges and the assignment of defense counsel to a case, the parties often negotiate over possible amendments to those charges. The defense attorney might request a dismissal of the most serious charge to be replaced by a less serious charge (a “vertical” charge bargain). Alternatively, the defense lawyer might ask for a dismissal of some charges in a multi-count indictment (a “horizontal” charge bargain). Both types of amendments reduce the maximum sentence that a judge could legally impose on the defendant.

Negotiations between the parties about revised charges take on even greater importance in the context of more highly structured sentencing systems. Sentencing laws that structure or reduce judicial discretion, including “mandatory minimum sentences” and “presumptive sentencing guidelines,” make the charge of conviction a more important predictor of the sentence. Once the defendant is found guilty of a particular crime, these highly structured sentencing laws give judges relatively few options for how to sentence the defendant (and perhaps no options at all). Because a structured sentencing environment makes visible the sentencing consequences of charging decisions, the parties can isolate the impact of a charge reduction and negotiate based on a more certain prediction of the outcome.

Mandatory minimum sentencing laws offer a clear-cut example of the impact of charge bargains on sentencing outcomes. These laws create “cliff effects” that dramatically affect the potential sentence, depending on whether the parties agree to the mandatory sentence versus a similar crime with no mandatory penalty attached. Mandatory penalties could lead to wholesale increases in sentence severity in a jurisdiction. Empirical studies confirm, however, that prosecutors selectively mitigate the impact of specific mandatory sentencing laws by dismissing or reducing charges in some cases (Bjerk 2005).

Presumptive sentencing guidelines tie sentencing options to the charge of conviction, much like mandatory minimum sentencing laws do. Systems that link the charge of conviction to a narrow range of sentence outcomes limit the options for the sentencing judge and empower the prosecutor, who controls both the filing of charges and the proof of the defendant’s conduct.

Empirical studies have examined what prosecutors in guideline jurisdictions actually do about charge reductions. For the least serious cases, studies found only small shifts from sentence bargains to charge bargains. Apparently, busy prosecutors in high-volume systems do not change their customary negotiation practices across the board.

Charge bargains increased more markedly, however, in more serious cases. In cases where conviction on the original charge would result in a presumed prison sentence and conviction on a lesser charge would allow probation or a shorter jail sentence, charge bargains happened more often after the arrival of sentencing guidelines in a jurisdiction. The amended rules gave the parties greater control over the sentencing outcomes in those cases, and they took advantage of that new power (Miethe 1987; Frase 2005). Research on the charging and plea bargaining practices of federal prosecutors under the federal sentencing guidelines also suggests that prosecutors frequently exercise their charge bargaining discretion to reduce sentences, particularly in drug and weapon possession cases (Bowman and Heise 2001). On the whole, the empirical evidence suggests that sentencing guideline systems make charge bargains somewhat more attractive than they are in discretionary sentencing regimes.

There are also questions about the equal distribution of charge bargain benefits. The presence of legally relevant facts is the most important determinant of the charge of conviction (i.e., the charge that ultimately forms the basis for the conviction). Some nonlegal factors, however, also have some effect on the charge of conviction. Factors such as the race of the defendant appear to have a relatively small but persistent impact on the outcomes (Steffensmeier et al. 1998).

Defense Concessions

While the prosecutor can offer reduced sentences to the defendant, the defense attorney also holds certain bargaining chips during plea negotiations. Each of the defendant’s concessions involves the removal of procedural hurdles from the prosecutor’s path.

The defendant’s power to make the government’s work easier begins with the investigation. If the defendant cooperates in an ongoing investigation, the government might be able to convict additional defendants. This form of assistance is especially important in the federal system. The discounts available for “substantial assistance” lead to some difficult anomalies in the sentences among defendants who commit their crimes as part of a group, with the largest discounts awarded to the most blameworthy (and knowledgeable) organizers of the criminal enterprise (Maxfield and Kramer 1998).

Another procedural hurdle that the defendant can remove for the prosecution is discovery and disclosure. The prosecution has a constitutional duty to disclose all material exculpatory information in its possession and a duty under state statutes or procedural rules to respond to any discovery requests for certain types of inculpatory evidence. The defendant, however, can remove most of those obligations from the prosecution by pleading guilty.

The most valuable concessions that defendants make in plea negotiations are waivers of pretrial hearings and the trial itself. These waivers might extend to all the procedural rights at trial, including the right to a jury, confrontation of adverse witnesses, counsel, and so forth. In some jurisdictions, defendants can obtain some benefits by offering to waive the jury trial in favor of a bench trial (Schulhofer 1984).

The defendant can also offer the government certainty and finality of outcomes by waiving the right to appeal or to file post-conviction collateral attacks on the conviction. Most state and federal courts have concluded that a defendant may explicitly waive the right to appeal a conviction as part of a plea agreement. One empirical study of federal cases found that nearly two-thirds of the cases settled by plea agreement included a waiver of appeal rights and three-quarters of the defendants who waived appeal also waived collateral review (King and O’Neill 2005).

Prevalence Of Plea Negotiations

The concessions that the prosecutor and the defense attorney offer each other during plea negotiations have become the norm in criminal justice: plea agreements account for the great majority of convictions in every jurisdiction in the USA. The proportion of negotiated pleas changes over time and across different systems.

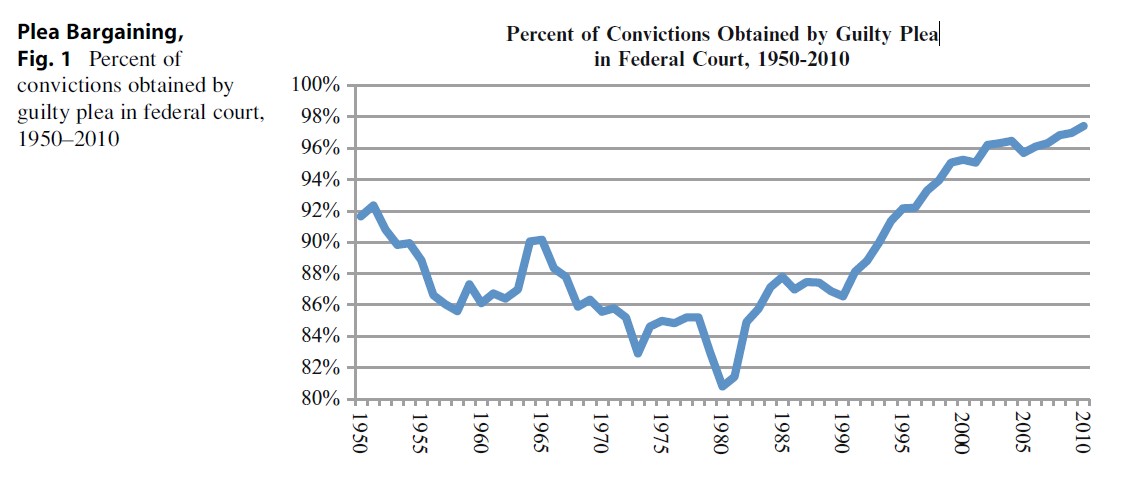

Negotiated outcomes were not at all common in the mid-nineteenth century in state systems (Fisher 2003). In the federal system, less than 8 % of convictions were obtained through guilty pleas in the early 1970s; that number rose inexorably through the decades to reach the current level, above 97 % (Wright 2005). See Fig. 1.

A high volume of cases within a court system – both the civil and criminal dockets – creates the conditions for plea bargaining to thrive (Bibas 2012). Courts that resort to plea bargaining, in turn, increase their caseloads even further. Routine practices and expectations also play a role in sustaining the institution of plea bargaining: some courts with relatively uncrowded dockets still depend almost entirely on negotiated pleas.

The United States is unusual in an international context in its heavy reliance on party negotiations to resolve criminal proceedings and the tight connection it promotes between plea negotiations and sentencing outcomes. For example, only a generation ago, Germany was known as the “land without plea bargaining” (Langbein 1979). Over time, however, many European nations have faced a higher volume of criminal cases; crowded court dockets have led to various innovations that allow the prosecutor to designate some cases for summary treatment.

In some countries, party negotiations to achieve these more streamlined criminal adjudications have become more common. Parties not only negotiate guilty pleas but also dismissals and diversion into alternative punishment or restitution programs (Jehle and Wade 2006; Luna and Wade 2010). In the past, these negotiated summary dispositions were restricted to less serious cases, but that limitation is disappearing over time (Langer 2004). Plea bargaining is somewhat more prevalent in Israel, Canada, Australia, England, and Wales than in European Continental countries.

Negotiation Effects

It is difficult to say whether plea bargains reduce the typical sentence imposed on a defendant over the long run. On the one hand, defendants who plead guilty to a crime receive a definite “discount” for waiving trial rights, when compared to defendants facing the same charges during the same time period. On the other hand, as the courts rely more heavily on plea bargains and prosecutors file more charges, the legislature tends to pass new criminal laws that increase the risk for defendants who refuse to plead guilty. That is, the new laws authorize higher sentences that defendants potentially face if they insist on a trial and lose. Over the long run, reliance on plea bargains does not correlate with reduced sentences (Pfaff 2011).

Other potential effects of plea bargains go beyond the sentences imposed, raising issues about the accuracy of system outcomes and the influence of different system actors.

Questions About Accuracy

Established constitutional doctrine declares that the courts may not punish a criminal defendant simply for exercising the constitutional right to a trial. Daily practice in every American criminal court, however, contradicts this doctrine. It is clear that defendants routinely receive more severe sentences after trial than they would receive if they were to plead guilty (Brereton and Casper 1981). Judges resolve this apparent conflict between constitutional doctrine and daily reality by declaring that they reduce sentences in guilty plea cases based on the defendant’s cooperative attitude and prospects for rehabilitation, and not based simply on the fact that the defendant waived trial rights.

The exact size of the “trial penalty” – or to put it more politely, the “guilty plea discount” – is difficult to measure. Studies of the trial penalty that attempt to control for the seriousness of the offense and other variables find a substantial gap between posttrial sentences and post-plea sentences. One study found a wide range of differences – between 13 % and 461 % – depending on the crime and the jurisdiction involved (King et al. 2005).

When defendants face such a large trial penalty, concerns start to mount that some defendants with valid defenses nevertheless plead guilty. Although there is a reasonable prospect that such defendants would be acquitted at trial, they dare not risk the large increase in the sentence that happens after a conviction at trial (Wright 2005). Behavioral economics offers some reasons to believe that defendants will undervalue the long-term impact of a felony conviction, leading defendants to accept a guilty plea too easily (Bibas 2004). On the other hand, there is evidence that some innocent defendants resist highly attractive plea offers, even when it might be rational to accept the offer in light of the risk of a wrongful conviction (Gazal-Ayal and Tor 2012).

The risk of coercing innocent defendants into pleading guilty is built into some basic structural features of American criminal justice. Criminal codes that offer more bargaining options to the prosecutor make it possible to increase the trial penalty and to pressure some defendants into waiving potentially effective defenses. The same holds true for increased sentence severity. When the law authorizes higher maximum sentences for a wide range of offenses and retains low potential sentences for lesser-included offenses, defendants face an enormous range of risk. Particularly in those states with sentencing guidelines or other limits on judicial sentencing discretion, the defendant can control some of that risk through a charge bargain. It would be an overstatement to claim that sentencing guidelines lead directly to more inaccurate convictions. They can, however, contribute to a coercive environment for defendants.

Finally, the structure of criminal justice institutions increases the risk of coercive and inaccurate guilty pleas. The public does not invest in enough judges, courtrooms, prosecutors, and public defenders to try a substantial proportion of the cases filed each year. The “working group” dynamic that develops in most courtrooms places the highest value on agreements that will move cases more quickly through the system (Nardulli et al. 1985).

Balance Of Power Among Sentencing Actors

Sentencing guidelines and other structured sentencing laws that began to proliferate in the 1970s were designed to regulate judicial discretion in sentencing. As a result, some critics of these laws expressed concern that the reforms would transfer power from judges to prosecutors. Compared to traditional indeterminate sentencing schemes, the more structured systems would concentrate sentence authority in one branch rather than allowing one institution to check and balance the other (Alschuler 1991).

The transfer of power hypothesis finds some tentative empirical support. For instance, studies of guideline systems confirm that charge bargains become more common for at least some crimes, and charge reductions determine an important component of the sentence actually served (Frase 2005). But this shift in charging practices may not result in a provable transfer of authority from judges to prosecutors since judges might find other methods to influence sentences (Engen 2008).

At the very least, fears that prosecutors would entirely usurp the judge’s sentencing authority in presumptive guideline jurisdictions appear to have been overstated. For one thing, judges in an indeterminate sentencing system do not, in reality, control the sentence that an offender actually serves. The judge announces one sentence, but parole authorities could later reduce that sentence. Since the judge in an indeterminate system never held actual power over the sentence to be served, guidelines do not take that power away from the judge. It is also true that presumptive sentencing guidelines leave important zones of discretion available to judges in the selection of sentences.

Limits On Prosecutorial Discretion

Legal institutions place some controls on the negotiation of guilty pleas. Those constraints originate both from outside the office of the prosecutor and from the internal workings of a local prosecutor’s office.

External Constraints

If the legislature defines crimes narrowly and sets penalties at modest levels, it reduces the risks of inaccurate convictions and increases the power of different sentencing actors to check each another. This approach to crime legislation, however, does not thrive in the American political climate. Voters expect prosecutors to take the lead in addressing crime, and they expect legislators to give them the legal tools to do the job. Legislators respond with broadly worded criminal laws and multiple statutes (each with a different corresponding punishment) that could apply to a single common factual scenario.

Although legislators do not seriously constrain prosecutors through the terms of the substantive criminal law, statutes in a few jurisdictions do limit the timing of plea negotiations or limit the size of the charge reduction that a prosecutor can offer to dispose of a case (at least for some high priority categories of crime). While these legislative directives can be meaningful, their current impact is small. Statutory limits on the timing of negotiations simply push plea bargains into earlier phases of the proceedings.

Judges also refuse, for the most part, to monitor and control the negotiation of guilty pleas. Granted, judges hold the power to accept or reject guilty pleas, along with the plea agreements that the parties present to them. These judicial powers, however, operate within a system of mass justice. The caseload would become overwhelming if judges balked regularly at proposals to remove a case from the trial docket, or even took the time regularly to investigate this possibility.

The law in some jurisdictions also limits the role of the judge during plea negotiations. Statutes, rules of criminal procedure, rules of judicial ethics, and judicial opinions in more than half of the states instruct the judge not to “participate” at all in the plea discussions. The judge’s only role is to evaluate the legitimacy of the guilty plea after the parties finalize their agreement. A smaller number of states discourage judges from participating in plea negotiations, but they do not ban the practice outright. The laws in these states allow the judge to comment on the acceptability of charges and sentences that the parties themselves propose or to participate in the negotiations only upon the invitation of both parties.

The rules of professional responsibility as enforced by state licensing authorities are also a potential source of limits on the plea bargaining behavior of prosecutors. For instance, a prosecutor who withholds discoverable information from the defense during plea negotiations might violate the specialized ethical obligations of prosecuting attorneys. Again, however, we get limited accountability from these regulators. State bar authorities rarely discipline prosecutors, and the penalties are usually not severe (Zacharias 2001).

Although institutions external to the prosecutor’s office do not exert much power over the discretion of line prosecutors, the chief prosecutor is directly accountable to the voters. Prosecutors in the United States are normally elected. Given the distaste among voters for the practice of plea bargaining, elections in theory should limit the prosecutor’s ability to reduce charges or to recommend lower sentences as part of a plea negotiation. In practice, however, the influence of voters over the plea bargaining policies of the prosecutor’s office is limited. The heavy advantage of incumbents in prosecutorial elections makes this a weak accountability mechanism (Wright 2009).

Internal Constraints

While legal institutions outside the prosecutor’s office do not fully meet the need for checks and balances, internal regulation has a substantial constraining effect. Forces within the prosecutor’s office can produce plea policies that remain true to declared sources of law, in keeping with current public priorities in the enforcement of that law, applied with reasonable consistency across cases (Bibas 2012; Miller and Wright 2008).

These internal regulations take several forms. First, the managers in a prosecutor’s office sometimes arrange the flow of cases to encourage line attorneys to interact dispose of cases through plea negotiations. This might involve the use of “horizontal” prosecution for some crimes, with different attorneys or units in the office making decisions as a file moves up through the system. It is also common, particularly in larger offices, to require supervisor approval for any plea agreement that dismisses a charge in priority cases, such as homicide and domestic violence.

Second, chief prosecutors can promote consistency and fidelity to public values among their line attorneys by creating written guidelines for the disposition of cases (Podgor 2012). The United States Attorney’s Manual is one such resource. The guidelines typically declare that they do not carry the force of law and are not enforceable in judicial proceedings, but they nevertheless exert some control over the behavior of prosecutors (Abrams 1971). Through the use of such guidelines, prosecutors have from time to time banned the use of plea bargains for certain classes of cases, although such guidelines require serious monitoring and enforcement to remain effective.

While there is much promise in the power of chief prosecutors to hold their line prosecutors accountable, the system also depends on professional tradition, informal office culture, peer pressure, and individual conscience to achieve just results. At the end of the day, each prosecutor must remain individually committed to the ideal of responsible prosecution.

Policy Challenges

The most significant checks on the use of plea bargains come from inside prosecutors’ offices. Prosecutors in the United States are profoundly decentralized: the state courts operate over 2000 separate prosecutors’ offices, with no effective hierarchical control over the local offices in most states. As a result, the internal controls on plea bargains are often nontransparent and inconsistent from place to place. Policy makers who hope to promote enforcement of the criminal law that is consistent with legal values and with current popular priorities must find ways to make these local internal policies and practices more visible and subject to evaluation by the public and by other legal actors. A balance of power, in a transparent environment, would lead to the most responsible use of negotiated guilty pleas.

Bibliography:

- Abrams N (1971) Internal policy: guiding the exercise of prosecutorial discretion. UCLA Law Rev 19:1–58

- Alschuler AW (1976) The trial judge’s role in plea bargaining (pt. 1). Columbia Law Rev 76:1059–1154

- Alschuler AW (1991) The failure of sentencing guidelines: a plea for less aggregation. Univ Chic Law Rev 58:901–951

- Bibas S (2004) Plea bargaining outside the shadow of trial. Harv Law Rev 117:2463–2547

- Bibas S (2012) The machinery of criminal justice. Oxford University Press, New York

- Bjerk D (2005) Making the crime fit the penalty: the role of prosecutorial discretion under mandatory minimum sentencing. J Law Econ 48:591–625

- Bowman FO, Heise M (2001) Quiet rebellion? Explaining nearly a decade of declining federal drug sentences. Iowa Law Rev 86:1043

- Brereton D, Casper J (1981) Does it pay to plead guilty? Differential sentencing and the functioning of criminal courts. Law Soc Rev 16:45–70

- Engen RL (2008) Have sentencing reforms displaced discretion over sentencing from judges to prosecutors? In: Worral JL, Nugent-Borakove ME (eds) The changing role of the American prosecutor. State University of New York Press, Albany

- Fisher G (2003) Plea bargaining’s triumph: a history of plea bargaining in America. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto

- Frase RS (2005) Sentencing guidelines in Minnesota, 1978–2003. Crime Justice: A Rev Res 32:131–219

- Gazal-Ayal O, Tor A (2012) The innocence effect. Duke Law J 62:339–401

- Jehle JM, Wade M (2006) Coping with overloaded criminal justice systems: the rise of prosecutorial power across Europe. Springer, Berlin

- King NJ, O’Neill M (2005) Appeal waivers and the future of sentencing policy. Duke Law J 55:209–261

- King NJ, Soule DA, Steen S, Weidner RR (2005) When process affects punishment: differences in sentences after guilty plea, bench trial, and jury trial in five guidelines states. Columbia Law Rev 105:959–1009

- Langbein JH (1979) Land without plea bargaining: how the Germans do it. Mich Law Rev 78:204–225

- Langer M (2004) From legal transplants to legal translations: the globalization of plea bargaining and P the Americanization thesis in criminal procedure. Harvard Int Law J 45:1–64

- Luna E, Wade M (2010) Prosecutors as judges. Washington Lee Law Rev 67:1413–1532

- Maxfield LD, Kramer JH (1998) Substantial assistance: an empirical yardstick gauging equity in current federal policy and practice. United States Sentencing Commission, Washington, DC

- Miethe TD (1987) Charging and plea bargaining practices under determinate sentencing: an investigation of the hydraulic displacement of discretion. J Crim Law Criminol 78:155–176

- Miller ML, Wright RF (2008) The black box. Iowa Law Rev 94:125–196

- Nardulli PF, Flemming RB, Eisenstein J (1985) Criminal courts and bureaucratic justice: concessions and consensus in the guilty plea process. J Crim Law Criminol 76:1103–1131

- Pfaff JF (2011) The myths and realities of correctional severity: evidence from the National Corrections Reporting Program. Am Law Econ Rev 13:491–531

- Podgor ES (2012) Prosecution guidelines in the United States. In: Luna E, Wade M (eds) The prosecutor in transnational perspective. Oxford University Press, New York

- Schulhofer SJ (1984) Is plea bargaining inevitable? Harv Law Rev 97:1037–1107

- Scott RE, Stuntz WJ (1992) Plea bargaining as contract. Yale Law J 101:1909–1968

- Steffensmeier D, Ulmer JT, Kramer JH (1998) The interaction of race, gender, and age in criminal sentencing: the punishment cost of being young, black and male. Criminology 36:763–798

- Wright RF (2005) Trial distortion and the end of innocence in federal criminal justice. Univ PA Law Rev 154:79–156

- Wright RF (2009) How prosecutor elections fail us. Ohio State J Crim Law 6:581–610

- Wright RF, Miller ML (2002) The screening/bargaining tradeoff. Stanford Law Rev 55:29–118

- Zacharias FC (2001) The professional discipline of prosecutors. North Carol Law Rev 79:725–743

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.