This sample Sentencing Guidelines In The United States Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Sentencing guidelines have been a central part of criminal law reform efforts in the United States since the late 1970s. Through sentencing guidelines, many American jurisdictions have attempted – with varying degrees of success – to improve their criminal justice systems by combating judicial disparity; increasing fairness, honesty, and transparency; and, in some cases, controlling costs. While a majority of states do not have them, the presence of guidelines in the federal system and a substantial percentage of high-profile states have provided sentencing guidelines with considerable visibility.

Sentencing is where the rubber meets the road in the criminal law. All of the niceties of a criminal trial, in the statistically unlikely event there was one, are over. The defendant is guilty. The system must now choose how to respond and which actor or actors should have what degree of discretion. Sentencing guidelines are a popular American tool for helping to inform and implement those choices. Depending on the method of counting, there are at least 53 full criminal justice systems in the United States, one in each state plus the federal government, the District of Columbia, and the military. Each system must decide, within the constraints of the United States Constitution (and its own Constitution if applicable), how to punish convicted offenders. Sentencing guidelines, as befitting a tool used by different sovereigns reflecting different political and legal cultures, vary quite a bit from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. There are, however, some common questions that many drafters of sentencing guidelines – whether the judiciary, the legislature, or a sentencing commission – face.

This research paper will explore some of the fundamental aspects of sentencing guidelines, their structure, breadth, and challenges. This research paper will not examine sentencing guidelines or their analogues outside of the United States, nor will it focus more than necessary on the sentencing commissions that often promulgate sentencing guidelines as those bodies have their own entry in this series. It will also not address capital sentencing.

This research paper will, however, explore selected attributes and challenges of sentencing guidelines through the lens of some of the key sentencing guideline jurisdictions.

Fundamental Background Of And Structures For Sentencing Guidelines

How Should Sentencing Systems Be Described?

Terminology describing sentencing systems is frequently confusing. A common language is thus essential. Sentencing systems are either determinate or indeterminate. “Indeterminate systems use discretionary parole release while determinate systems do not. Determinate and indeterminate sentencing schemes can take various forms. Either sort of system may be discretionary or nondiscretionary [as to sentencing]. Discretionary systems – be they determinate or indeterminate – may be guided or unguided” (Chanenson 2005, pp. 382–383). Sentencing guidelines are a popular way to provide guidance to sentencing judges, especially in discretionary, determinate sentencing systems. As noted below, sentencing guidelines can have varying degrees of force and may be best conceived of as occupying a continuum of enforceability. Common, although necessarily imprecise, terms for the relative power of the guidelines include “presumptive” and “advisory.”

Why Do Some Jurisdictions Choose To Have Sentencing Guidelines?

Before the 1970s, the dominant approach to sentencing in the United States reflected a rehabilitative model and placed broad discretion in judges and parole boards. Judge Marvin Frankel and others questioned and criticized this highly discretionary approach as lawless and unfair. Academic commentators highlighted a “gross disparity in sentencing, with different sentences imposed upon similar offenders who have committed similar offenses by the same judge on different days, different judges on different days, different judges on the same day, and different judges in different jurisdictions” (Singer 1978, p. 402). US Supreme Court Justice O’Connor noted that unguided sentencing discretion “inevitably resulted in severe disparities in sentences received and served by defendants committing the same offense and having similar criminal histories. Indeed, rather than reflect legally relevant criteria, these disparities too often were correlated with constitutionally suspect variables such as race” (Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. 296, 315 (2004) (O’Connor, J., dissenting)).

Starting in the 1970s, as a result of these criticisms and other, sometimes local, concerns, various American jurisdictions reformed their approach to sentencing by implementing different forms of guidance. “One way to describe sentencing reform over the past half century is that law came to sentencing” (Miller 2004, p. 121). Some jurisdictions – most notably Minnesota and the federal government – abolished discretionary parole release and implemented a determinate system with sentencing guidelines. Other jurisdictions – most notably Pennsylvania – retained an indeterminate system but added sentencing guidelines. As the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has noted, sentencing guidelines “were promulgated in order to structure the trial court’s exercise of its sentencing power and to address disparate sentencing” (Commonwealth v. Mouzon, 812 A.2d 617, 620 n.2 (Pa. 2002) (plurality)). Federal sentencing reform was the product of years of discussion, debate, and political compromise. Some scholars have asserted that the final product, the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, reflected a “subtle transformation of sentencing reform legislation: conceived by liberal reformers as an anti-imprisonment and antidiscrimination measure, but finally born as part of a more conservative law-and-order crime control measure” (Stith and Koh 1993, p. 223).

Sentencing guidelines reflect the legal and policy choices of the jurisdiction. Thus, popular attitudes and opinion can play a significant role. Sentencing guidelines can spark intense debate in part because they are transparent. This law-based transparency “forces the resolution of issues of sentencing policy – and enforces the particular resolution – and thus makes the fact of resolution clear. This society is not of one mind on what values sentencing should embody and thus the resolution of these disputed issues means the values of some will prevail while those of others will not” (Boerner 1993, p. 174).

What Kinds Of Structural Choices Do Legislatures Make When Starting This Process?

There are different ways to structure a sentencing system. Each jurisdiction must confront at least three common structural choices. First, should sentencing be determinate or indeterminate? Many commissions and guidelines – including in the Minnesota and federal systems – emerged as part of a package of legislation that abolishes discretionary parole release, which transforms the system from an indeterminate one to a determinate one. Other guidelines – like Virginia – began within an indeterminate structure, but the legislature transitioned to a determinate approach later for reasons similar to those motivating the Minnesota and federal systems. Finally, there are a couple of jurisdictions – most notably Pennsylvania – that continue to have both an indeterminate structure (meaning discretionary parole release) and well-developed sentencing guidelines.

Second, which actor in the system should promulgate the guidelines? In part because of their popularity and specialized expertise, permanent sentencing commissions have captured the lay imagination concerning guideline creation and maintenance, but they are not the only approach. It is possible for the legislature or the judiciary to create guidelines either themselves or through temporary bodies established for that purpose. Even when it creates a sentencing commission, the legislature often reserves for itself the power to formally create the guidelines or at least a veto power over the guidelines promulgated by the commission. A popular approach, exemplified by the federal and Pennsylvania systems, involves the sentencing commission issuing guidelines which take effect after a predetermined amount of time unless the legislature and executive affirmatively block them. This power-sharing arrangement is often described in a positive light as allowing the commission to act on its expertise with less political pressure than elected officials might feel while still respecting principles of democratic accountability.

Third, how much binding force should the guidelines have? Not all guidelines have the same amount of binding force. As exemplified by the original Minnesota and the federal approaches, powerful guidelines were initially a popular approach. Many felt that anything less binding would not rein in judicial discretion. Before a new interpretation of the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution emerged in the early 2000s, the federal guidelines were very binding (often called “presumptive”) and judges would frequently have difficulty successfully justifying sentences that diverged from the presumptive guideline range, a process called “departing.” In fact, the rigid nature of the federal guidelines – and the associated relative lack of judicial discretion – attracted severe and persistent criticism.

Terminology here can be challenging as labels like “presumptive” and “advisory” can mask many variations. Indeed, “there are an infinite number of stops between a purely advisory approach and a completely mandatory framework” (Reitz 2005, p. 157). However, a jurisdiction can influence how much power the guidelines (and, at times, functionally the prosecutor) have as opposed to the judge. One indication of a more voluntary guideline regime, exemplified by Virginia, is the absence of appellate review. The presence of appellate review generally reflects more binding guidelines, but the intensity of that review can vary widely. Releasing judge-specific sentencing information may also have an impact on guideline compliance as well as reflect a commitment to transparency (Bergstrom and Mistick 2003). It is interesting to note that Pennsylvania, a state in which judges run for election and stand for retention, releases judge-specific information while the federal government, in which judges are appointed for life, does not.

More binding or presumptive guidelines are arguably desirable because they have sufficient teeth to meaningfully limit judicial discretion. However, more advisory, and thus less binding, guidelines are arguably desirable because they provide sufficient judicial flexibility to promote fairness in a particular case. Just as there can be unwarranted disparity, there can also be unwarranted uniformity. Professor Doug Berman observed that “reformers believed that sentencing guidelines, by codifying standards which would direct judges’ sentencing decisions in most but not all cases, could reduce sentencing disparities and maintain sentencing flexibility, while promoting the development of principled sentencing law and policy” (Berman 2000, p. 35). Ultimately, each jurisdiction has to find its own balance between individualization and uniformity of sentences.

How Do Sentencing Commissions Create Sentencing Guidelines?

Guideline drafters have a myriad of choices to make, and the American constitutional structure affords them substantial latitude within which to work. There are at least six decisions that can be characterized as critical:

- What Philosophical Goals Should Animate the Guidelines?

The legislature and/or the sentencing commission should address what philosophical goals of sentencing should be reflected in the guidelines. The standard debates about purposes of punishment play out in this process. While the rehabilitative model had been dominant, people like criminologist and law school Dean Norval Morris successfully urged that punishments should be limited by principles of just deserts. Morris argued that desert is “an essential link between crime and punishment. Punishment in excess of what is seen by that society at that time as a deserved punishment is tyranny” (Morris 1974, p. 76). Most systems have embraced Morris’ idea of “limiting retributivism,” pursuant to which the offender’s desert defines the upper and lower limits of acceptable (not unjust) punishment and within that range other utilitarian goals can be pursued (Frase 2005, pp. 76–77).

Although most modern American sentencing systems are now largely retributive, guideline drafters often struggle with how to articulate their views and integrate competing ideas. The United States Sentencing Commission officially sidestepped the question at the macro level when it promulgated the first set of federal guidelines in 1987. It noted that, “[a] philosophical problem arose when the Commission attempted to reconcile the differing perceptions of the purposes of criminal punishment…. Adherents [to both “just deserts” and “crime control” approaches] urged the Commission to choose between them, to accord one primacy over the other…. A clear-cut Commission decision in favor of one of these approaches would diminish the chance that the guidelines would find the widespread acceptance they need for effective implementation. As a practical matter, in most sentencing decisions both philosophies may prove consistent with the same result” (U.S. Sentencing Commission 1987, Ch 1A 1.3–1.4). Nonetheless, some scholars of federal sentencing have argued that the federal guidelines reflect a “modified just desert” theory in which “the greatest weight in determining sentences is given to matching the severity of punishment to the seriousness of the present offense,” and the second most significant consideration is “the need to incapacitate for longer periods the more dangerous offenders” determined by criminal history (Hofer and Allenbaugh 2003, p. 24). This seems to be consistent with, if not a variant of, “limiting retributivism.”

Putting these pieces together is not easy. Professor Frase summed it up by noting that “early guidelines reforms attempted to narrow the focus of sentencing to strongly emphasize uniformity and ‘just deserts,’ and to promote more rational sentencing policy. The much broader range of contemporary sentencing goals demonstrates an important underlying truth, which early guidelines reforms (and some recent proposals) seem to have overlooked: sentencing policy is very complex, requiring compromise and careful balancing of numerous, often-competing goals” (Frase 2000, pp. 435–436).

- Should the Guidelines Be Descriptive or Prescriptive?

Sentencing guidelines can be designed primarily to reflect past judicial practices which can be described as a “descriptive” approach. This has the benefit of more likely acceptance by the judiciary as it will seem familiar in most cases, but it may not always produce the most desirable results. When the Virginia guidelines were promulgated, they enjoyed strong judicial support in part because they were largely descriptive. On the other hand, sentencing guidelines can be designed from the ground up to reflect what the sentencing commission believes is the best path even if it diverges from past judicial practice. This can be described as a “prescriptive” approach. Minnesota used a more prescriptive strategy in part to encourage incarceration for violent offenders and discourage it for property offenders. The prescriptive path may have the benefit of a more rational approach, but could encounter opposition from lawyers and judges who are accustomed to the old ways. As with so many things, the common responses can be plotted along a continuum with the bulk of guidelines avoiding the extremes.

- Should the Guidelines Be Based More on a “Real” or a “Charge” Offense Model?

Which crime(s) should matter when sentencing a defendant? At first blush, it may seem like an odd question to ask. Should the defendant only be sentenced on the crime(s) for which he has been convicted? Does that mean that the judge must ignore compelling evidence of other criminal acts that, for whatever reason, were not the subject of the jury’s guilty verdict or the defendant’s guilty plea? On the other hand, should the defendant be sentenced based on every bad thing that the government alleges – and supports with proof at less than the beyond a reasonable doubt level – the defendant has ever done? Does that mean that the judge must factor in the amount of cocaine allegedly involved in a second drug charge on which the jury returned a verdict of not guilty? The restrictive approach is, at the extreme, described as “charge offense” sentencing while the inclusive approach is, at the extreme, described as “real offense” sentencing.

Charge offense sentencing runs the risk of the judge being prevented from sentencing based on everything known about the offender and the offense. It is also criticized for perhaps making it even easier for prosecutors to control the system by bringing more charges against some defendants and fewer charges against others. Real offense sentencing runs the risk of the defendant being punished on the basis of weak allegations that a jury either rejected or was never even given the chance to consider. While the extremes of both approaches may strike many people as preposterous, jurisdictions do stake out positions leaning toward one side or the other. Pennsylvania, for example, is largely a charge-based system, although judges may consider information about other behavior in exercising sentencing discretion. The federal system, in contrast, enshrines a fairly aggressive real offense scheme in its guidelines. Judges must calculate the guidelines on the basis of “relevant conduct,” which encompasses acts similar to the offense of conviction. This relevant conduct must be included as long as it is proven by a preponderance of the evidence even if the government never charged those acts or the jury, employing the beyond a reasonable doubt standard, acquitted on them.

- How, If at All, Should the Guidelines Address Multiple Convictions?

Guideline systems struggle to deal with multiple convictions. Many people would agree that multiple offenses usually deserve greater punishments than a single offense of the same nature. But how much more? Should the increase be geometric? Is a “volume discount” appropriate for the multiple burglar? Some guidelines require consecutive sentences for certain types of offenses, such as violent crimes, but mandate concurrent sentences for other offenses, such as property crimes. Other jurisdictions, like Pennsylvania, do not speak to multiple convictions at all and thus afford the judge nearly unfettered discretion to impose sentences concurrently or consecutively. Then-Judge (now US Supreme Court Justice) Breyer criticized that discretionary model by observing that “[a] moment’s thought suggests, however, that this approach leaves the prosecutor and the judge free to construct almost any sentence whatsoever” (Breyer 1988, p. 26). The federal system tries to avoid those extremes by creating a “system that treats additional counts as warranting additional punishment but in progressively diminishing amounts” (Breyer 1988, p. 27). While this federal approach may be more satisfying in theory, the practical result is a fairly byzantine process with nearly algebraic calculations that itself has been the subject of significant criticism.

- How Should the Guidelines Deal with Mandatory Minimum Sentences?

Despite the existence of sentencing guidelines which are designed to take a nuanced approach, many legislatures continue to create mandatory minimum provisions. Mandatory minimum sentence laws are often criticized as being crude, inconsistently applied, and in tension with the idea of sentencing guidelines. US Supreme Court Justice Breyer, who was an influential member of the original US Sentencing Commission, noted that mandatory minimum sentences “prevent the Commission from carrying out its basic, congressionally mandated task: the development, in part through research, of a rational, coherent set of punishments…. Most seriously, they skew the entire set of criminal punishments, for Congress rarely considers more than the criminal behavior directly at issue when it writes these provisions…” (Breyer 1999, p. 184). Many sentencing commissions have to decide how to respond to such conflicting legislative directives. For example, Congress created both the federal sentencing guidelines system and a series of gun and drug mandatory sentences in close succession. In fact, the mandatory sentences were passed before the new commission could even promulgate the first set of guidelines.

There are two broad responses available to a sentencing commission. First, it could ignore the mandatory minimum sentences when crafting its guidelines. This allows the guidelines to reflect the views of the sentencing commission and simply be trumped by the mandatory minimum sentences when they apply. Doing so has the potential of creating a sentencing “cliff,” which is a point where a small change in offense behavior prompts a large change in the sentence. For example, the commission may set relatively modest weight-based guidelines for a drug offense. If the amount of the drug involved reaches the level that triggers the mandatory minimum sentence, however, the defendant’s sentence may increase precipitously. Sentencing cliffs are frequently criticized because of the perceived unfairness of the sharp increase in sentencing severity in response to the incremental increase in offending severity. Alternatively, the commission could accommodate the mandatory minimum scheme by integrating it into its guideline recommendations. This approach, largely followed in the federal system, avoids the “cliff” problem but requires the guidelines to be driven by the mandatory minimum sentences in a way that may diverge from what the sentencing commission would have otherwise done. The result may be greater severity for a wider swath of offenses and offenders. The Pennsylvania guidelines, providing another example of how broad labels can conceal variations, have largely declined to accommodate mandatory minimum sentences for its core recommendations. However, the guidelines have engaged with and attempted to provide alternatives to mandatory minimum sentences by providing such things as advisory sentence enhancements for conduct that might otherwise trigger mandatory minimums. It is interesting to note that Pennsylvania adopted a guideline system in part to “avoid mandatory minimum legislation that would severely restrict judicial discretion” (Kramer and Ulmer 2009, p. 15).

- How Should the Sentencing Recommendations Be Communicated?

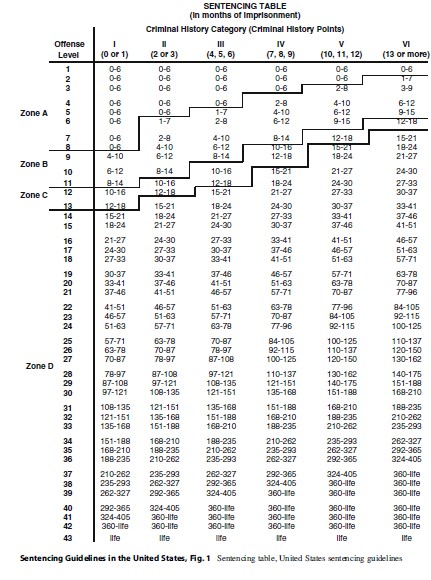

The most common way to reflect the jurisdiction’s sentencing choices and recommendations is through a simple two-axis grid, although there are other approaches such as narratives. This two-axis grid commonly reflects the defendant’s criminal history along the horizontal axis and the severity of the crime along the vertical axis. Where those two paths intersect is the box or cell containing the guidelines’ recommended sentence or sentencing range, which is often expressed in months of incarceration (see Fig. 1).

Some jurisdictions, including Minnesota and Pennsylvania, have different grids for certain crimes (like sex offenses) or different ways in which crimes are committed (like with the possession or use of a deadly weapon). These separate grids are often explained as a way to reflect the particular seriousness of the targeted behavior without skewing the recommended sentences for the majority of offenses. This approach has been praised for limiting the impact of popular pushes for severity to the target offenses/ offenders and has also been criticized for allowing that push for severity concerning those offenses/offenders to proceed more easily by bifurcating it from the bulk of cases.

The Mechanics Of The Federal Sentencing Guidelines

Sentencing guidelines require the judge and lawyers to engage in a series of calculations that yield a particular recommendation, often as represented by a box or cell on the guideline grid. Guideline calculations vary in complexity depending on the jurisdiction. The federal system is widely viewed as the most complicated and is often criticized on that basis. Despite its distinctive federal complexities, a review of the kinds of calculations a federal judge needs to make before imposing a sentencing may afford a useful window on guideline sentencing generally.

There are 43 levels of what the federal guidelines call “offense seriousness” (US Sentencing Commission). In order to determine the ultimate offense level, the judge starts with the “base offense level” for the offense of conviction. Logically, offenses the Commission deems to be more serious are assigned a higher base offense level. The judge must then consider “specific offense characteristics,” which are factors related to the offense such as the amount of money taken in a robbery or the quantity of drugs trafficked. The more the judge finds as taken or trafficked, the greater the increase in the offense level. At this point, the federal system’s modified real offense feature can sweep in conduct for which there was no conviction. Next, the judge must determine whether any “adjustments” apply. Adjustments are not offense-specific and include such matters as the defendant’s role in the offense (as a major or minor participant) and whether the defendant obstructed justice. Adjustments often increase a defendant’s offense level, but they can reduce it as well, as in the case of a minor participant. The judge then must consider whether there are multiple counts of conviction. As noted above, the federal system employs a complicated formula to give an incremental increase for multiple offenses. Next, the judge evaluates whether the defendant has “accepted responsibility” for his offense. This often correlates with a guilty plea. If the defendant has accepted responsibility, his offense level will be reduced by either two or three offense levels. The resulting number is the defendant’s offense level, which is represented on the vertical axis in the Sentencing Table (see Fig. 1). The horizontal axis reflects the defendant’s criminal history. The judge assigns criminal history points for previous convictions of various types and whether the defendant was under judicial supervision at the time of the offense. These points translate into a “Criminal History Category.” There are six Criminal History Categories. Where the offense level and the Criminal History Category intersect is the defendant’s guideline range.

The US Sentencing Commission recaps the process this way. “The final offense level is determined by taking the base offense level and then adding or subtracting from it any specific offense characteristics and adjustments that apply. The point at which the final offense level and the criminal history category intersect on the Commission’s sentencing table determines the defendant’s sentencing guideline range” (US Sentencing Commission, p. 3). An offense level of 19 and a Criminal History Category of I, which is where a first-offender would be classified, yields a guideline range of 30–37 months. If the defendant was in Criminal History Category VI, which is the highest possibility, the guideline range would be 63–78 months.

Despite having calculated the guideline range, the judge is not ready to impose a sentence. Next, the judge must evaluate whether this is an unusual case warranting a different sentence under the guidelines. “[I]f an atypical aggravating or mitigating circumstance exists, the court may ‘depart’ from the guideline range. That is, the judge may sentence the offender above or below the range” (US Sentencing Commission, p. 3). For years, the availability of departures under the federal guidelines was a topic of frequent litigation and vigorous debate. Many critics argued that the appellate courts and the federal sentencing commission took an inappropriately crabbed view of these kinds of departures and that the fairness of the sentences often suffered. Yet judges did depart at times and could do so either up or down the offense level axis or left or right along the Criminal History Category axis. Since the Supreme Court of the United States made the federal guidelines “effectively advisory” (see below), judges must also consider whether the guidelines are appropriate in this case in light of the authorizing statute which invokes the traditional purposes of punishment as well as a parsimony provision. The judge may impose a completely different sentence if the judge believes that the guideline range does not meet the dictates of the statute, although the sentence is subject to appellate review for “unreasonableness.”

The Sixth Amendment’s Shifting Sands

Until approximately 2004, several guideline systems – especially the federal system – relied on facts that judges found at sentencing by a preponderance of the evidence in order to determine the presumptive sentencing range. “The top of the presumptive range was below the traditional statutory maximum for the offense of conviction. The actual sentence imposed might be higher or lower than the presumptive range, in part because of judicially found aggravating or mitigating facts” (Chanenson 2005, p. 378). In a series of decisions (including Blakely v. Washington and United States v. Booker) interpreting the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees the right to a trial by jury, the Supreme Court of the United States functionally invalidated crucial aspects of these presumptive guideline systems. The Court held these schemes unconstitutional because judges were allowed “to impose sentences higher than the presumptive guideline range based on facts found by the judge, using the preponderance of the evidence standard, instead of by the jury, using the beyond a reasonable doubt standard” (Chanenson 2005, p. 378). The key, according to the Court, was that a judge could not impose a sentence that exceeds the statutory maximum which, for these purposes, it defined as the “maximum sentence a judge may impose solely on the basis of the facts reflected in the jury verdict or admitted by the defendant” (Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. at 303). The Court emphasized that “the relevant ‘statutory maximum’ is not the maximum sentence a judge may impose after finding additional facts, but the maximum he may impose without any additional findings” (Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. at 303).

This could have been a mortal blow to federal sentencing guidelines, which was a heavily presumptive system and relied on significant judicial fact finding. However, the Supreme Court provided an escape hatch. These presumptive systems had two primary options. First, juries could be asked to find all of the facts beyond a reasonable doubt that judges had been finding by a preponderance of the evidence. This would then authorize the judge to impose a sentence in the same guideline range as in the past. While some jurisdictions went in that direction, many did not in part because of the factual and logistical challenges of asking juries to decide such sentencing facts as a defendant’s role in the offense. This expanded role for the jury would have been particularly difficult for the federal sentencing system to adopt because it was both highly presumptive and required judges to make numerous factual determinations at sentencing, which now juries would have to make. The second option involved recasting the formerly presumptive guidelines as advisory. If the guidelines are just advisory, the judge has the ability to ignore the guidelines’ advice and the power to impose a sentence up to and including the traditional statutory maximum, which is almost always higher than what the guidelines recommend. This is the path the federal system followed. However, neither the US Sentencing Commission nor the Congress made that change. Rather, it was the Supreme Court itself that recast the federal guidelines in this way. The Court construed the federal guidelines as “effectively advisory” in order to avoid the need to strike down the system as unconstitutional (United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005)). In doing so, it also broadened many people’s conception of what it means for a system to be “advisory,” as federal judges must still consider the guidelines and the sentences they impose are still subject to appellate review, albeit under a less stringent standard of review.

Broader Questions And Emerging Practices

Intermediate Punishments And Misdemeanors

Intermediate punishments have been the subject of discussion – and practice – for many years. Norval Morris and Michael Tonry have argued:

We are both too lenient and too severe; too lenient with many on probation who should be subject to tighter controls in the community, and too severe with many in prison and jail who would present no serious threat to community safety if they were under control in the community. (Morris and Tonry 1990, p. 3)

It is thus unfortunate and somewhat surprising given the size and scope of community corrections programs that guidelines relating to intermediate punishment are not common. Some jurisdictions – like Pennsylvania and North Carolina – have addressed this issue to various degrees, but it remains an underdeveloped area (Frase 2000, pp. 439. –442; Frase 1999, pp. 77–78).

It is also interesting to note that relatively few guideline systems apply to both misdemeanors and felonies (Frase 2000, p. 429).

Guideline “Effectiveness”

The “effectiveness” of sentencing guidelines is often a topic of intense discussion and disagreement. Part of the disagreement flows from differing definitions of success and varying methodological views on examining the relevant issues. Overall, many believe that sentencing guidelines can be and have been effective along particular metrics, including disparity reduction, in certain circumstances (U.S. Sentencing Commission 2004, xiv–xvi, 135, 141; Frase 2000, p. 443). For example, Professor Michael Tonry has written that “[g]uidelines promulgated by commissions have altered sentencing patterns and practices, reduced sentencing disparities and gender and race effects, and shown that sentencing policies can be linked to correctional and other resources, thereby enhancing governmental accountability and protecting the public purse” (Tonry 1993, p. 713). To be sure, not every jurisdiction succeeds on every metric all the time, but if one accepts that an increase in transparency and a decrease in judicial disparity were key goals of sentencing guidelines, there are reasons to be encouraged.

Sentencing guidelines have also had some success in the realm of controlling costs. At a minimum, many sentencing commissions have become trusted sources of information for legislatures as they debate broad penal strategies. Some commissions, particularly Minnesota and North Carolina, have tried to respect financial restraints as they promulgate guidelines. More recently, Missouri started providing information about the financial consequences of particular sentencing decisions to judges in individual cases.

However, if one is focused more on controlling prosecutorial discretion (and the disparity that may flow from that discretion) sentencing guidelines have not been effective. As some predicted early on, there is a widely held view that prosecutorial power has increased after the introduction of sentencing guidelines. “Since guidelines limit the range of sentences available for a given offense, the power to drop or not drop charges is the power to select the sentence range available to the court (that is, what ‘box’ on the grid the case ends up in). Thus, any disparity in charging translates into disparity in sentencing” (Frase 1999, p. 77). It must be recognized that most sentencing guidelines do not speak to the prosecutorial role directly and were never intended to do so, despite the wishes of some.

Similarly, if one is focused on controlling prison populations, sentencing guidelines have not been particularly effective. The incarceration rate in the United States has risen precipitously in the last 30 years. Some jurisdictions have succeeded in curbing the growth of their prison population, but it is more than debatable whether the existence or nonexistence of guidelines is the dispositive feature. Sentencing guidelines are tools to implement broad policy in a manner that promotes systemic rationality and individual fairness. To that extent, there is reason to believe they can be – and often are – “effective.” Sentencing guidelines are not inherently severe or lenient any more than fire is inherently a force for good (warmth and cooking) or evil (arson and destruction). “The experience in Minnesota and Washington, progressive states generally regarded as having the most successful guidelines systems, teach that while those systems were effective at restraining the growth of prison populations when that was the policy of those states, they were equally effective at implementing policy judgments that more punitive sentences were appropriate” (Boerner 1993, p. 176).

Evidence-Based Practices And Risk

Selected jurisdictions have started to consider how, if at all, they should incorporate evidence-based practices, including risk assessment, in their sentencing systems. While there are some echoes from the pre-guidelines era’s interest in rehabilitation, the emphasis today is quite different. The focus now is on how reliable social science evidence can inform sentencing determinations – at the level of the guidelines and/or the individual sentencing judge – in a way that will reduce recidivism and thus improve public safety. Former Missouri Chief Justice Mike Wolff, who facilitated the inclusion of risk assessment information in Missouri’s Sentencing Assessment Reports (its version of presentence investigation reports), has argued that, “We must acknowledge that the reason for sentencing is to punish, but if we choose the wrong punishments, we make the crime problem worse, punishing ourselves as well as those who offend” (Wolff 2008, p. 1395).

Virginia is the undisputed pioneer in integrating risk assessment into sentencing guidelines. Pursuant to a 1994 legislative directive, the Virginia Criminal Sentencing Commission explored whether an empirically based risk assessment tool could help judges divert “25 % of the lowest risk, incarceration-bound, drug and property offenders for placement in alternative (non-prison) sanctions” (Kern and Farrar-Owens 2004, p. 165). At the legislature’s request, the Virginia commission later broadened the eligibility to additional low-risk offenders. If the risk instrument indicates that the qualifying offender is of sufficiently low risk, the Virginia guidelines, which are advisory and without appellate review, recommend the offender for an alternative sanction. The judge remains free to accept or reject that recommendation. A few years later, the Virginia legislature asked the commission to develop a risk assessment tool for sex offenders with the goal of identifying those with the highest risk of reoffending. In 2001, this instrument was integrated into the Virginia guidelines by increasing the upper end of the recommended range by varying amounts for higher risk offenders (Kern and Farrar-Owens 2004, p. 167). Again, the judge retains discretion and may, but need not, impose a sentence that takes advantage of the expanded sentencing range while remaining in compliance with the guidelines.

Pennsylvania is also weaving risk assessment into its sentencing guidelines. Under Pennsylvania’s guidelines, the duration and intensity the recommended non-incarcerative sentence for certain drug-involved offenders has long reflected the treating of professional’s judgment concerning treatment needs. Pursuant to a 2010 legislative directive, the Pennsylvania commission is now working to integrate an actuarial risk assessment instrument into the guidelines. While Pennsylvania may not follow the precise path blazed by Virginia, it is also trying to use risk assessment “to assist in the transparent – and thus accountable – decision-making by both the Commission at the policy level and judges… at the individual level” (Hyatt et al. 2011, p. 748).

There are many reasons to be cautious about risk assessment, and many policy makers and judges are quite wary, if not suspicious, of this approach. By definition, risk assessment deals with predictions and not certainties. No actuarial instrument will ever be 100 % accurate. Yet, policy makers and judges have long engaged in predictions of risk based on their clinical judgment – or gut instinct – which itself is not only imperfect, but research indicates is often less accurate than actuarial instruments (Gottfredson and Moriarty 2006). Sentencing remains deeply normative and predictions about recidivism will never – and should never – be the only consideration. Actuarial risk assessment is simply a tool that guideline systems can use to help inform judicial discretion.

Not only does risk assessment raise crucial questions concerning how to distribute punishment, but it also can prompt reflection on the severity of punishments. If a less severe sentence does not diminish – and may even improve – public safety in certain situations, was society’s initial punitive judgment sound? There are no immutable answers, but the questions themselves can be important.

Concluding Observations

Sentencing guidelines have helped to refashion the landscape of American criminal justice, and they are continuing to do so. Even jurisdictions that do not yet have guidelines may be attracted by their promise of a more rational, transparent, and just approach to punishment. Indeed, the American Law Institute seems likely to recommend that all American jurisdictions adopt guidelines. Sentencing guidelines, however, remain very much a work in progress. All guidelines systems have flaws and many of them are glaring, but those same flawed systems often provide a mechanism for experimentation and, one hopes, positive refinement (Frase 2000, p. 445). Professor Michael Tonry summed it up this way:

Like all calls for just the right amount of anything, not too much and not too little, a proposal for sentencing standards that are constraining enough to assure that like cases are treated alike and flexible enough to assure that different cases are treated differently is a counsel of unattainable perfection. Nonetheless, that is probably what most people would want to see in a just system of sentencing… (Tonry 1996, pp. 185–186).

Sentencing guidelines offer a real opportunity to strive for that “unattainable perfection.”

Bibliography:

- Allen F (1981) The decline of the rehabilitative ideal: penal policy and social purpose. Yale University Press, New Haven

- Bergstrom M, Mistick J (2003) The Pennsylvania experience: the public release of judge-specific sentencing data. Fed Sentencing Rep 16:57–61

- Berman D (2000) Balanced and purposeful departures: fixing a jurisprudence that undermines the federal sentencing guidelines. Notre Dame Law Rev 76:21

- Boerner D (1993) Bringing law to sentencing. Fed Sentencing Rep 6:174–177

- Breyer S (1988) The federal sentencing guidelines and the key compromises upon which they rest. Hofstra Law Rev 17:1–50

- Breyer S (1999) Federal sentencing guidelines revisited. Fed Sentencing Rep 11:180–186

- Chanenson S (2005) The next era of sentencing reform. Emory Law J 54:377–460

- Frankel M (1973) Criminal sentences: law without order. Hill and Wang, New York

- Frase R (1999) Sentencing guidelines in Minnesota, other states, and the Federal Courts: a twenty-year retrospective. Fed Sentencing Rep 12:69–82

- Frase R (2000) Is guided discretion sufficient? Overview of state sentencing guidelines. St Louis Univ Law J 44:425–446

- Frase R (2005) Punishment purposes. Stanf Law Rev 58:67–83

- Freed D (1992) Federal sentencing in the wake of the guidelines: unacceptable limits on the discretion of sentencers. Yale Law J 101:1681–1754

- Gottfredson S, Moriarty L (2006) Statistical risk assessment: old problems and new applications. Crime Delinq 52:178–200

- Hofer P, Allenbaugh M (2003) The reason behind the rules: finding and using the philosophy of the federal sentencing guidelines. Am Crim Law Rev 40:19–85

- Hyatt J, Chanenson S, Bergstrom M (2011) Reform in motion: the promise and perils of incorporating risk assessments and cost-benefit analysis into Pennsylvania sentencing. Duq Law Rev 49:707–749

- Kern R, Farrar-Owens M (2004) Sentencing guidelines with integrated offender risk assessment. Fed Sentencing Rep 16:165–169

- Kramer J, Ulmer J (2009) Sentencing guidelines: lessons from Pennsylvania. Lynne Rienner, Boulder

- Miller M (2004) Sentencing reform “reform” through sentencing information systems. In: Tonry M (ed) The future of imprisonment. Oxford University Press, New York

- Morris N (1974) The future of imprisonment. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Morris N, Tonry M (1990) Between prison and probation: intermediate punishments in a rational sentencing system. Oxford University Press, New York

- Reitz K (2005) The enforceability of sentencing guidelines. Stanf Law Rev 58:155–173

- Singer R (1978) In favor of “presumptive sentences” set by a sentencing commission. Crime Delinq 24:401–427

- Stith K, Cabranes J (1998) Fear of judging: sentencing guidelines in the federal courts. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Stith K, Koh H (1993) The politics of sentencing reform: the legislative history of the federal sentencing guidelines. Wake Forest Law Rev 28:223–290

- Tonry M (1993) The success of judge Frankel’s sentencing commission. Univ Colo Law Rev 64:713–722

- Tonry M (1996) Sentencing matters. Oxford University Press, New York

- United States Sentencing Commission (1987) U.S. sentencing guidelines manual. http://www.ussc.gov/guidelines/1987_guidelines/Manual_PDF/1987_Guidelines_Manual_Full.pdf

- United States Sentencing Commission (2004) Fifteen years of guidelines sentencing: an assessment of how well the federal criminal justice system is achievingthe goals of sentencing reform. http://www.ussc.gov/Research/ Research_Projects/Miscellaneous/15_Year_Study/15_year_study_full.pdf

- United States Sentencing Commission. An overview of the federal sentencing guidelines. http://www.ussc.gov/ About_the_Commission/Overview_of_the_USSC/ Overview_Federal_Sentencing_Guidelines.pdf

- Wolff M (2008) Evidence-based judicial discretion: promoting public safety through state sentencing reform. N Y Univ Law Rev 83:1389–1419

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.