This sample Health Systems of Sub-Saharan Africa Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

The primary purpose of health systems is to improve health. Health systems comprise people, institutions, and all activities whose primary purpose is to promote, maintain, or restore health in the population. The World Health Organization (WHO) World Health Report 2000 emphasizes that health systems concerned with bettering health must address issues of goodness and equity, in addition to individual physical and mental well-being. Goodness relates to how well the system responds to people’s expectations (responsiveness), and equity refers to fairness of the systems. Health systems have to provide financial protection against the cost of ill health. A good health system is measured according to its attainment and performance. Attainment measures what health systems achieve with respect to: good health, responsiveness, and fair financial contribution. Performance compares attainments with what health systems should be able to accomplish, that is, attaining the best achievable results with the resources available.

Health systems cannot be held responsible for socioeconomic differences in the population that influence health disparities. However, they can be accountable for excess deaths and illness resulting from diseases that are preventable and/or curable. Governments carry the ultimate responsibility for the performance of national health systems. Governmental stewardship (protecting the public interest) drives the responsibility for the health of the population and thus the quality and efficiency of the health systems.

An analysis of health system performance in sub-Saharan Africa necessarily involves evaluating efficiency and quality of the provision of care. The roles of providers and healthcare managers are an important component of performance. Dually important is the ability of consumers to access the health system, and their overall engagement with the system. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa seldom evaluate health systems performance, hence their inability to detect inequalities and other problems. Without performance evaluation, populations who experience economic, social, and political marginalization will continue to be unattended.

Composition Of Health Systems In Sub-Saharan Africa

The wide diversity of health-care arrangements in the region involves both biomedical and traditional health systems.

Biomedical System

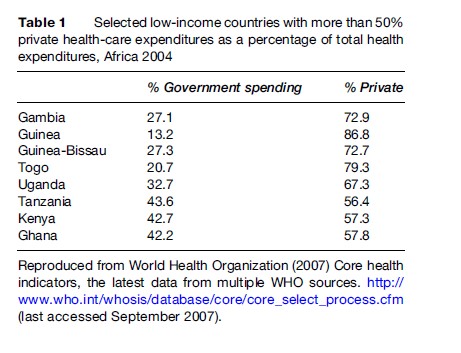

In sub-Saharan Africa health systems operate within a complex and changing environment. There are many institutions involved in health care beyond the ministries of health (MOH). These are made up of national and international institutions, each with their own responsibilities. In addition to governmental contribution, private for-profit and not-for-profit or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) including faith-based organizations are also involved in the provision and financing of health-care services. In many low-resource countries of sub-Saharan Africa, where the public sector has failed to meet the demand for health care of the populations, NGOs and the private sector have stepped in to provide essential services. Table 1 shows examples of low-income countries in the region by level of health-care expenditures as a percentage of total health. Additionally, changes in financing and markets in these countries have affected private sector development. Despite investments in health systems, many countries are falling short of their performance potential, augmenting burden of disease experienced by poor and vulnerable populations. Health ministries have largely focused on managing the public sector. However, given the current growing private sector contribution, there is a need for governments to use the resources of the private and NGO sectors to actualize optimal health system performance. The breakdown between public, private, and NGO health-care sectors varies throughout sub-Saharan Africa. In some countries, two-thirds of health-care services are provided by the public sector, and one-third is a combination of private and NGO sectors (e.g., in Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Madagascar). In other countries, private and NGO contribution in service delivery surpass that of the public sector (e.g., in Tanzania, Malawi, Uganda, and others). Of all countries in the region, South Africa has seen the largest increase of private health-care sector provision (excluding contributions from NGOs). In the republic of Tanzania, for example, half of all private hospitals and 3% of health centers are privately operated (Castro-Leal et al., 2000).

The gap left from the private and public health coverage is often filled by the voluntary sector. These NGOs carry out the roles of social service providers in an effort to provide support to poor and vulnerable populations. NGOs are managed separately from the public sector, although they may receive government funding. Similar to other health professions, NGOs are primarily motivated by humanitarian concern. There are several types of NGOs operating within the health sector of sub-Saharan Africa: religious organizations, international and local NGOs, professional associations, and many others registered as not-for-profit organizations. They remain major providers of services in areas that lack access to public health services. Benefiting from their separation from government bureaucracy, NGOs have a greater ability to innovate and react quickly to changing needs.

In a 1994 policy paper, Gilson et al. identified four primary health-care sector functions of NGOs:

- Service provision: NGOs provide health-care services similar to those provided by government or private companies. NGOs typically serve a different population that may be underserved in these other sectors. In Zimbabwe and Tanzania, 80–90% of church hospitals are in rural areas without other providers (Gilson et al., 1994). This high percentage of charitable organizations providing services in rural areas is very common even today in many other countries in the region. NGOs also work in urban slums and with other marginalized populations.

- Social welfare activities: NGOs recognize the link between social status and health, and work to provide essential services to underserved groups. In this group we can include NGOs that are involved in caring for the disabled, children, or youth, such as the international social welfare organizations Save the Children Fund and CARE.

- Support activities: NGOs may support government health-care activities such as supplying low-cost drugs, training the health-care workforce, and other activities that lead to better functioning of the health-care system. In general, African church organizations train their own health-care workers with variable degrees of government oversight. In Tanzania, for example, the government sets the standards and certifies the qualifications of health-care workers graduating from church schools. In Uganda the drugs for the NGO sector are centrally purchased by the Joint Medical Stores, operated by the Catholic and Protestant boards.

- Research and advocacy: NGOs have the ability to influence overall policy regarding health systems. They make a significant contribution to policy changes by effectively lobbying for the provision of free antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Health-care programs run by NGOs can become models for larger public sector services. If the small scale of NGOs limits their replication potential on the national level, they may still garner community support to influence health-care structure. Many NGOs have a research arm in addition to a service arm, which they use to examine health interventions.

Perception of quality of services provided by NGOs tends to be higher than that of the state. A study in Tanzania found that 45% of participants preferred to use an NGO facility because of availability of drugs and services (Mujinja et al., 1993). However, another Tanzanian study found negative quality indicators in NGO health worker performance (Gilson, 1992). However, the case of

Tanzania seems not to be the norm in sub-Saharan Africa. Better perceived quality in the NGO sector may itself lead to higher utilization, thereby increasing efficiency of service provision. Conversely, if services are viewed as being of low quality, utilization and efficiency may be below that of government services.

In sub-Saharan Africa the NGO health-care sector has been plagued by management issues, resulting in inefficiencies. NGOs have the ability to integrate closely into a community and address specific needs. This asset may also hinder the NGOs’ abilities to translate their work onto a national level and secure funds to larger resource areas. Relations between NGOs and national health-care systems are not always symbiotic or communicative. Umbrella organizations seek to improve coordination between these groups, and facilitate dialogue that involves community members as well. In Ghana, NGOs register their facility and medical staff with appropriate governmental agencies. Health information systems are coordinated and data are collected by the umbrella organization, Christian Association of Ghana (CHAG). Other countries in the region have similar structures. The Malawi church organizations’ members of the Christian Association of Malawi provide health-care benefit from purchasing drugs from the Government Central Medical Store at subsidized prices.

Traditional Healing System

The biomedical system seems to predominate in sub-Saharan Africa. However, the region has significant cultural healing traditions that cannot be overlooked. Traditional healing systems refer to health practices that incorporate plants, roots, animal and mineral-based therapies, spiritual therapies, and rituals, used individually or in combination to diagnose, prevent, and treat diseases. According to the WHO, in Africa up to 80% of the population uses traditional medicine for primary health care (WHO, 2003). In many instances both the biomedical and the traditional healing systems are used for management of the same episode of disease. Evidence from Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, and Zambia shows that 60% of children with high fever resulting from malaria use as a first line of treatment some form of traditional medicines at home before using conventional treatment (WHO, 2003). Scientific evidence related to the efficacy of the traditional healing systems is for the most part deficient. Results of the use of traditional healing systems can vary from no effect to negative or even a dangerous effect.

Research is needed to ascertain the efficacy of most practices and medicinal plants widely used to treat the leading diseases that cause death and disability. One such disease is HIV/AIDS. It is estimated that in South Africa 75% of people living with HIV/AIDS use traditional medicines (WHO, 2003). A study by Babb et al. (2004) showed that in a workplace clinic in South Africa in which an antiretroviral (ART) program had been recently launched, the majority of the clients were also using traditional medicine. These traditional medicines were given primarily by traditional healers and herbalists, and about 21% of the users obtained products from their own yards and fields. The potential for drug interaction in this case is unknown, but users were for the most part satisfied with the results, and had no side effects to report.

Access To Health-Care Systems

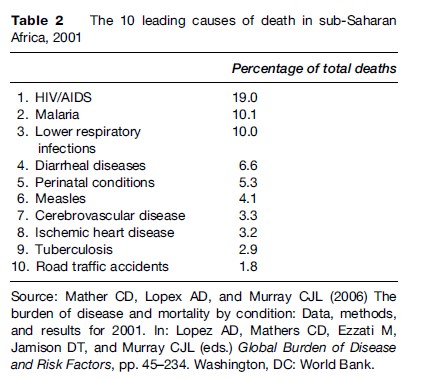

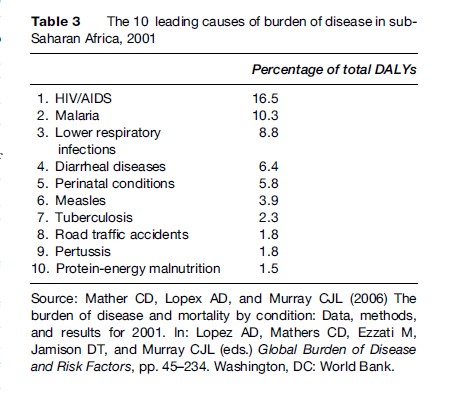

Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, health care operated on a three-tiered system, moving from basic primary care facilities to district and secondary health facilities, and finally to tertiary specialty hospitals. Resources are generally concentrated at the tertiary level, where treatments are most costly. Allocation of resources to the tertiary level results in inequities, as the poor are less likely to seek hospital care. As Castro-Leal et al. (2000) noted, about one-quarter of budgets are dedicated to primary care services. Some of the most burdensome diseases in these countries – acute respiratory illness, diarrhea, and malaria – are all cared for in these chronically under- funded primary care sectors (Table 2). While some of these diseases are largely preventable and treatable, they are often not adequately addressed by the health system, resulting in high associated morbidity and mortality (Table 3). In Madagascar, research estimated that 90% of illness could be prevented by strengthening the primary care sector.

As a result of inadequate primary care services, the poor are more inclined to self-treat than the rich, even in the case of serious illness. A study in Chad (Leonard, 2005) found that treatment of malaria outside of the health-care system is widespread, resulting in increased incidence and prolonged morbidity from the disease. Additionally, the cost to the government for visits to a clinic is normally less costly than visits to a hospital or referral center. Government’s response has been to subsidize curative services to the poor. However, Castro-Leal found that the poorest quintile’s care was subsidized less than the richest quintile. Reallocating subsidies and spending to primary care to reach the poor is a step in the right direction. However, research supports that budget adjustments must be met with changes in utilization by poor households (Castro-Leal et al., 2000).

There are a myriad of factors that contribute to the underuse of health services. Income has a significant effect on the demand for health care. As governments implement cost recovery schemes by increasing user fees, the poor use services less. To meet the demand of the poor in the public sector, wealthier patrons should be served in the private sector. Issues of market instability often prevent this more equitable shift from occurring. Castro-Leal and colleagues (2000) found evidence in Madagascar and Ghana that there are differences in the quality of care delivered at different facilities, based on budget allocations. This disadvantage is transferred to the poor that visit the lower-funded facilities. Rural isolation leads to reduced health-care access for vulnerable populations throughout Africa. Castro-Leal et al. (2000) also found that in South Africa the poorest 20% of the population must travel an average of over 2 hours to reach medical attention, while the richest 20% travel an average of 34 minutes. A study in Ghana found that halving the distance to public health facilities increased utilization by 96% (Lavy and Germain, 1994). Gertler and van der Gaag (1990) found that the poor in Cote d’Ivoire were more sensitive to changes in the distance traveled to a health facility than the rich. Socially marginalized groups within the poor are further disadvantaged when it comes to health care. If a household has limited resources to treat sick members, a hierarchy of needs may result in women and children forgoing treatment. Together, this evidence suggests the need for appropriately located services that reduce travel time and target specific vulnerable populations. Continuity of services within the health-care sector can be emphasized through training of providers at the hospital level to work in the primary care sector. For the long term, strategies should target increasing private sector services, so that governmental subsidies can be directed at the poor populations who need primary care services.

Epidemiological information and cost–benefit analysis help countries emphasize essential services aimed at the diseases that account for the large and avoidable health burdens. This approach has led many countries, including South Africa, to focus on primary care services, as well as HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and childhood illness care.

In the past decade, South Africa has developed a comprehensive primary health-care information system, based on an essential data set used to monitor the performance of the health system (Shaw, 2005). The large scale of health programs within the country (pertaining to HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, women’s health, and immunization) necessitates collection of large amounts of data. However, managers’ primary concerns are with the functioning of programs rather than with the collection of information. Gathering and reporting data for different projects is often duplicative, as managers must juggle multiple collection instruments. Local managers are often disconnected from the vision for usage of data collected on the facility of community level. These uncoordinated collection tools resulted in poor quality of data. In a 2005 article, Vincent Shaw describes how South Africa therefore moved to implement an essential data set as a main component of the District Health Information System (DHIS). DHIS began reviewing data collected on a facility level in 1994, when the new South African government began emphasizing primary health care and required an increasingly decentralized management structure and greater access to health information. Health workers evaluated local services and compiled a comprehensive list of 75 indicators and data elements that would accurately monitor necessary services. These essential indicators provided management with an integrated system to monitor all programs, and review information needs over time. South Africa applied to concept of a hierarchy of information needs to allow each level within the health services to develop their own data set within a larger system-wide framework. This framework has been highly effective for disseminating useful information on the local and national level.

The Primary Health Care (PHC) system in Nigeria (Chukwuani et al., 2006) was instituted in 1978 as a component of the country’s national development plan. Health status indicators are poor in Nigeria: the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) human development index for 2006 ranks it as 159th out of 177 countries. Poor health conditions combined with an inefficient health delivery system result in failed efforts for disease abatement. The health-care system has continuously struggled against economic crisis, creating dependence on international donor support. These donors tend to focus on a vertical model of disease control, as opposed to emphasizing broader prevention and program sustainability efforts. Despite recent recognition of the need for improvement and support of the PHC system, many countries lack the funds, vision, or infrastructure to move forward. Acknowledging the connection between health and economic development, the Nigerian government launched a comprehensive reform program of the PHC. Primary health services were decentralized to local government areas until 1991, structured around one comprehensive health center serving as referral center for four PHCs, each in turn serving as a referral center for five PHC clinics. In 1991 this structure was changed to include a health post in each village, a health clinic for groups of villages, and a comprehensive health center or hospital for each local government area. The PHC in Nigeria includes components of health education, agriculture and nutrition, sanitation, safe water supply, childhood immunization, control of locally endemic disease, essential drug provision, injury treatment, and mental and oral health.

Traditionally, health sector reform performance is measured through the health status of the population, satisfaction of users, and the degree to which citizens are protected from financial risks or ill health. Nigeria lacks a coherent health information system, so data on overall population health are scarce. Chukwuani et al. (2006) evaluated the reformed PHC sector through analysis of citizen satisfaction and access in southeastern Nigeria, finding a lack of operational efficiency. Facilities were found to be poorly maintained and did not have enough skilled health workers. Many health centers operate without a budget or management. Stewardship was found to be lacking, as few facility stakeholders knew of health policies or recordkeeping procedures. Surveys of community members analyzed service-seeking behavior. Private and general hospitals were most frequently patronized, while the PHC sector was least frequently visited. Nigeria has little regulation of private health-care providers, even though many of them provide PHC services. There appears to be a common perception of reduced quality of services from local or primary health-care centers. Quality is often linked to outcomes of care and therefore biased against primary or preventative health services. Policy research by Lewis et al. (2004) found that short wait times and drug access in private facilities are valued highly in comparison to community health settings. However, many Nigerian households cannot afford private care, creating an inequity of services. Malaria was recorded as the most important reason for a hospital visit. Lack of access to drugs, transportation, and ability to pay for health services pose significant barriers to citizens seeking health-care services. Quality of facilities is determined by the availability of skilled workers and managers. Nigeria falls short in this important determinant, as adequately trained personnel are lacking in rural areas. In resource-poor settings, organization of the PHC levels should be in accordance with the services that they have the capacity to provide. Health systems should, to the best of their ability, use their information systems as an effective tool to evaluate health equity and design appropriate interventions.

Governments have responded to the inadequacy of primary care services by decentralizing their health systems. This has involved modification of structure and at times differential resource allocation.

Financing Health-Care Systems

According to the WHO (2000), approaches used for the financing of health services can have an impact on how fairly the burden of prepayment is distributed. Spreading the risk and subsidizing the poor should be one of the goals. One approach is pooling, whereby collected revenues are transferred to purchasing organizations. The other approach is direct government subsidy. These two approaches are practiced to some extent in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The main purpose of pooling is to share the financial risk of health-care interventions. (For more information on the equity and efficiency of pooling in health-care financing, see Smith and Witter, 2004).

Research in sub-Saharan Africa has demonstrated the failure of health systems to support the needs of the significant, impoverished populations of the region (Castro-Leal et al., 2000). Some of this failure is due to inadequate governmental spending to develop appropriate healthcare systems and inefficient and ill-directed use of funds. The Castro-Leal et al. study analyzing the poor’s benefit from the health-care systems in Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Madagascar, South Africa, and Tanzania found that public spending designed to benefit the poor often benefits the better off. Poor households access services differently than wealthier households based on availability, cost, and perceived quality. Poorer households are less likely to report illness than wealthier households, perhaps due to lack of education of acceptance of the burden of illness. Perception of illness may differ according to spiritual beliefs and cultural norms as well. Wealthier groups tend to rely on public care, despite more ability to pay for services in the private sector.

Evidence from South Africa defies this trend, with richer groups seeking private care. Private care is also an important resource for poor populations in Ghana, South Africa, and Tanzania. A review of the primary care private sector in South Africa found that while costs and satisfaction were similar to that of the public sector, public health impact was substantially reduced (Palmer et al., 2003). The poorest populations were left without coverage. This research suggests encouraging governments to provide funding and oversight to private organizations in their outreach to the poorest populations.

Poor funding, management, and infrastructure are the most significant contributors to the inefficiency of the PHC systems in sub-Saharan Africa. The budgeting system is limited by lack of information on the most pressing needs and associated costs. The survey by Chukwuani et al. (2006) in Nigeria found that only 4.2% of the population could make significant contributions financing their health care. This creates significant challenges for resource mobilization to move the health system toward sustainability and away from donor dependency. This study also noted that communities were willing to pay more for better quality services, and were not opposed to paying user fees or health insurance fees. Sub-Saharan African primary health-care systems could be strengthened through the implementation of standard operating procedures, cost determination studies, incentives for health-care workers, and working to improve community perception.

Lack of accessible health care in rural or resource-poor settings leads to the nonlicensed sale of medications by drug vendors. In Chad, this has led to a phenomenon of self-medication for serious conditions such as malaria. Inability to pay for a physician consultation drives people to self-diagnose and seek alternative sources of treatment. Research in Chad demonstrated that self-medication is effective only in reducing symptoms and is rarely curative (Leonard, 2005). Thus people live in states of chronic disease, reducing ability to work and carry out daily life tasks. Rural drug vendors provide the only source of treatment in many regions and are a necessary and relied-upon part of the health system. Many countries, such as Ethiopia and Nigeria, have chosen to educate and train these vendors in the sale of drugs.

The application of user fees for health care has been the subject of considerable debate among researchers and policy makers. Some argue that user fees will encourage use as people place additional value on health care and see quality improve through increased funding (Ellis, 1987; World Bank, 2004). Others argue that user fees will further obstruct health care from poor households in sub-Saharan Africa, resulting in decreased utilization (Creese, 1997; Nyonator and Kutzin, 1999; Gilson and McIntyre, 2005). Research from Ghana demonstrated a significant drop in use of health services following an increase in user fees. In Kenya, numbers of male visitors to sexual health clinics dropped by 40% after the introduction of user fees for public health services. User fees are cost-sharing initiatives, designed to boost revenue to the health-care system. These fees can be instituted through governmental directives, or through a community-driven process. A study in Uganda that specifically evaluated community-initiated, cost-sharing schemes found that utilization increased in remote areas (Kipp et al., 2001). These programs directed user fees to the suppliers of services in an effort to give incentives to underpaid health workers. This research paper points to the relative effectiveness of community-based ‘bottomup’ rather than government-regulated ‘top-down’ cost recovery schemes. It also demonstrates the importance of local people being empowered to decide how the financing of schemes should operate and what staff incentive payments should be.

Kenya implemented user fees in 1991 following a steady rise in the demand for health care. After government implementation across the health-care sector, attendance dropped by 50% (Mwabu et al., 1995). The government then suspended the user fees because it saw no improvement in quality or increase in revenue from the implementation. Attendance rose by 41%, and people moved back to government hospitals from the private sector. Pervasive budget constraints drove Kenya to reexamine user fees once again, although in this case the government chose to implement the fees in a phased manner. The public acceptance of user fees was much greater after this phased system, in which households had time to adapt to the higher fees. Inequalities in service allocation still existed in the phased system, demonstrating that the poor must be exempted from user fees for health care.

Out-of-pocket expenditures for health can be considered the most regressive way to pay for health care. In sub-Saharan Africa this is a common practice, even among the poorest segments of the population. One way to assess whether health systems are fairly financed is to look at the share of out-of-pocket expenses in total spending. Revenue collection therefore has an impact on the equity of health systems.

Conclusion

Strengthening health systems should be a priority in sub-Saharan Africa. Failing to do so will continue to result in very large numbers of preventable deaths and disabilities in the region. The poor are without doubt the most affected by the poor performance of health systems by experiencing the refusal of those systems to provide basic health-care services.

Bibliography:

- Babb DA, Pemba L, Seatlanyane P, et al. (2004) Use of traditional medicine in the era of antiretroviral therapy: Experience from South Africa. International Conference on AIDS 2004. July 11–16, 15: Abstract No. B10640.

- Castro-Leal F, Dayton J, Demery L, et al. (2000) Public spending on health care in Africa: Do the poor benefit? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78: 66–78.

- Chukwuani CM, Olugboji A, Akuto EE, et al. (2006) A baseline survey of the primary healthcare system in south eastern Nigeria. Health Policy 77(2): 182–201.

- Creese A (1997) User fees. British Medical Journal 315: 202–203.

- Ellis RP (1987) The revenue generating potential of user fees in Kenyan government health facilities. Social Science and Medicine 25(9): 995–1002.

- Gertler P and van der Gaag J (1990) The Willingness to Pay for Medical Care: Evidence from Two Developing Countries. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Gilson L (1992) Value for Money?: The Efficiency of Primary Health Care Facilities in Tanzania. PhD Thesis: University of London.

- Gilson L and McIntyre D (2005) Removing user fees for primary care in Africa: The need for careful action. British Medical Journal 331: 762–765.

- Gilson L, Sen PD, Mohammed S, and Mujinja P (1994) The potential of health sector non-governmental organizations: Policy options. Health Policy and Planning 9(1): 14–24.

- Kipp W, Kamugisha J, Jacobs P, et al. (2001) User fees, health staff incentives, and service utilization in Kabarole district, Uganda. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 79(11): 1032–1037.

- Lavy V and Germain J-M (1994) Quality and cost in health care choice in developing countries. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Leonard L (2005) Where there is no state: Household strategies for management of illness in Chad. Social Science and Medicine 61: 229–243.

- Lewis M, Eskeland G, and Traa-Valerozo X (2004) Primary health care in practice: Is it effective? Health Policy 70(3): 303–325.

- Mujinja P, Urassa D, and Mnyika K (1993) The Tanzanian public/private mix in national health care. Paper prepared for January 2003 workshop on the public/private mix. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- Mwabu G, Mwanzia J, and Liambila W (1995) User charges in government health facilities in Kenya: Effect on attendance and revenue. Health Policy and Planning 10(2): 164–170.

- Nyonator F and Kutzin J (1999) Health for some? The effect of user fees in the Volta region of Ghana. Health Policy and Planning 14(4): 329–341.

- Palmer N, Mills A, Wadee H, et al. (2003) A new face for private providers in developing countries: What implications for public health? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81(4): 292–297.

- Shaw V (2005) Health information system reform in South Africa: Developing an essential data set. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83(8): 632–636.

- Smith P and Witter N (2004) Risk pooling in health care financing: Implications for health system performance. Health Nutrition and Population discussion paper. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Bank (2004) World Development Report 2004: Making services work for poor people. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2000) World Health Report 2000. Health systems: Improving performance. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2003) Traditional Medicine. Fact sheet No. 134. Revised May 2003. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs134/en/print.html (last accessed September 2007).

- AbouZahr C and Boerma T (2005) Health information systems: The foundations of public health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83(8): 561–640.

- Bateman C (2006) Rural health care delivery set to collapse. South African Medical Journal 96(12): 1219–1221, 1224–1226.

- Berman P (1997) National health accounts in developing countries: Appropriate methods and recent applications. Health Economics 6(1): 11–30.

- De Allegri M, Kouyate´ B, Becher H, et al. (2006) Understanding enrolment in community health insurance in sub-Saharan Africa: A population-based case-control study in rural Burkina Faso. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 84(11): 884–889.

- Evans DB, Adam T, Edejer TT-T, Lim SS, Cassels A, and Evans TG (2005) Choosing interventions that are cost effective: Time to reassess strategies for improving health in developing countries. British Medical Journal 331: 1133–1136.

- Evans DB, Edejer TT-T, Adam T, and Lim SS (2005) Choosing interventions that are cost effective: Methods to assess the costs and health effects of interventions for improving health in developing countries. British Medical Journal 331: 1137–1140.

- Evans DB, Lim SS, Adam T, and Edejer T (2005) Choosing interventions that are cost effective: Evaluation of current strategies and future priorities for improving health in developing countries. British Medical Journal 331: 1457–1461.

- Homsy J, King R, Tenywa J, Kyeyune P, Opio A, and Balaba D (2004) Defining minimum standards of practice for incorporating African traditional medicine into HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and support: A regional initiative in eastern and southern Africa. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 10(5): 905–910.

- Howard LM (1991) Public and private donor financing for health in developing countries. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America 5(2): 221–234.

- Jamison DT and Sandbu ME (2001) WHO ranking of health system performance. Science 293 (5535): 1595–1596.

- Kamadjeu RM, Tapang EM, and Moluh RN (2005) Designing and implementing an electronic health record system in primary care practice in sub-Saharan Africa: A case study from Cameroon. Informatics in Primary Care 13(3): 179–186.

- Kofi-Tsekpo M (2004) Institutionalization of African traditional medicine in health care systems in Africa. African Journal of Health Sciences 11(1–2): i–ii.

- Morel CM, Lauer JA, and Evans DB (2005) Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies to combat malaria in developing countries. British Medical Journal 331(7528): 1299.

- Mutemwa RI (2006) HMIS and decision-making in Zambia: Re-thinking information solutions for district health management in decentralized health systems. Health Policy and Planning 21(1): 40–52.

- Mwabu G (1990) Financing health services in Africa: An assessment of alternative approaches. Policy Research Working Paper, Series 457. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Nolan B and Turbat V (1995) Cost Recovery in Public Health Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Nolen LB, Braveman P, Dachs NW, et al. (2005) Strengthening health information systems to address health equity challenges. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83(8): 561–640.

- Rommelmann V, Setel PW, Hemed Y, et al. (2005) Costs and results of information systems. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83(8): 561–640.

- Schneider H, Blaauw D, Gilson L, Chabikuli N, and Goudge J (2006) Health systems and access to antiretroviral drugs for HIV in Southern Africa: Service delivery and human resources challenges. Reproductive Health Matters 14(27): 12–23.

- Soeters R, Habineza C, and Peerenboom PB (2006) Performance-based financing and changing the district health system: Experience from Rwanda. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 84(11): 884–889.

- Van Damme W and Kegels G (2006) Health system strengthening and scaling up antiretroviral therapy: The need for context-specific delivery models: Comment on Schneider et al. Reproductive Health Matters 14(27): 24–26.

- Waters HR, Morlock LL, and Hatt L (2004) Quality-based purchasing in health care. International Journal of Health Planning and Management 19(4): 365–381.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.