This sample Health Systems of Western Europe Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Background And Context

Europe is a region of approximately 50 independent states, of which 27, largely in the west and center, are now members of the European Union. The concept of ‘western Europe’ refers loosely to those countries situated to the west of the line that demarcated Soviet and NATO spheres of influence from the end of World War II until 1990. Western Europe includes the countries of Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland) to the north; Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal to the south: the UK and Ireland to the northwest, and France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and the Benelux countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg) in the continental center. This region has a combined population of almost 400 million.

By the end of the 20th century, and in most cases long before, almost all of these people were guaranteed access to health care paid for by a publicly mandated scheme. After pensions, health care is in most of these countries the largest component of public budgets. It is a major source of employment, scientific and industrial innovation, and economic growth. Not least for these reasons, but also because health has such existential significance, health is the stuff of much public debate and political attention (Freeman, 2000).

That European states are also health-care states is the effect of industrialization and of more or less continuous economic prosperity. The health systems of western Europe are the product of democratic politics, liberal and pluralist, in which parties and pressure groups make key contributions to the formulation of public policy. Their development is driven by managed capitalist economies of some kind. They are, at the same time, the realization of a science based medicine, supported by vigorous and influential pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries.

Health Systems In Western Europe

At the center of the system is the health-care system, founded on scientific biomedicine and consisting of the activity of one or more accredited physicians in relation to disease located in an individual patient body.

This system exists in an uncertain relationship with other complementary or alternative forms of healing, incorporating some and competing with others. These other forms include naturopathy, homeopathy, and chiropractic and are provided in different ways in different countries. They are not usually part of standard welfare entitlements, but are delivered by independent practitioners operating in the marketplace.

Meanwhile, above and beyond (and arguably behind) systems of health care are those of public health, meaning those measures designed to protect the health of the public, which include workplace safety, food standards, health education, and immunization programs, among a range of other services and regulations.

Health-Care Systems

Health systems, as we describe them here, are the formal arrangements by which health care is provided and paid for in European countries. By the beginning of the 21st century, these invariably are highly differentiated, complex systems of interlocking institutions and organizations (Marmor et al., in press). Because they are themselves so extensive and sophisticated, such systems require extensive and sophisticated forms of regulation to maintain them. Respective arrangements for health-care provision, finance and regulation are considered in more detail below. We begin, however, by noting common patterns into which such arrangements fall.

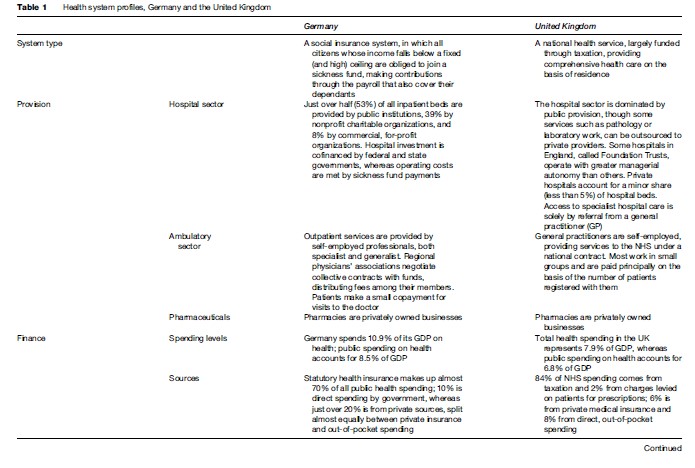

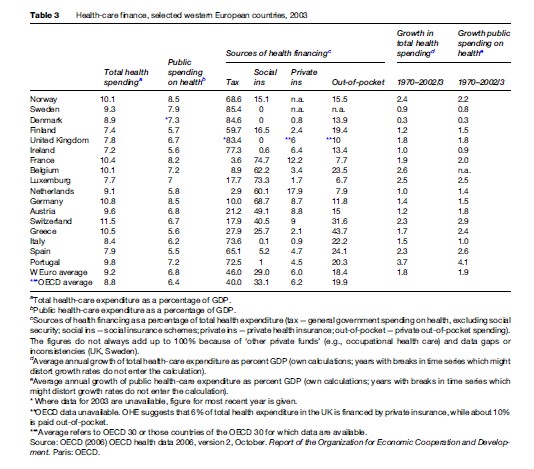

Two kinds of health-care system predominate in western Europe: social insurance systems and national health services (NHS); for a comparison, see Table 1. Social insurance schemes are financed by contributions paid by their members into what for most of them are compulsory schemes organized according to district, occupation, or workplace. Funds and groups of funds contract with providers, usually groups of hospitals and doctors’ associations, to provide care to their members (insurance benefits usually also include sick pay). Hospitals may be owned and run by regional or local governments, by nonprofit foundations, or as profit-making enterprises. Doctors are either employed by hospitals or work independently in local practice. This kind of system is often described as self-governing to the extent that its management depends on the outcome of negotiations between financing and provider agencies, while the role of government is to set framework conditions and directions.

National health services, by contrast, are financed for the most part by government from tax revenues. Most hospitals are state-owned and -run, and most doctors are either public sector employees or independent contractors to public sector organizations. Patient entitlement to health care is on the basis of citizenship or residence. As in social insurance systems, there is a limited role for private insurers and for commercial providers. The system as a whole is clearly a government responsibility, though it may often be delegated to regional levels.

National health services tend to predominate in northern and southern Europe (in the UK, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland; in Italy and Greece; and in Spain and Portugal), social insurance systems in the center and west (in France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxemburg, Austria, and Switzerland). Since 1990, most countries of central and eastern Europe have replaced integrated, state-led health services with social insurance schemes.

As these country profiles illustrate, brief descriptions and classifications of health systems are inevitably crude. All classifications are dependent on particular judgments about particular characteristics, and such simple statements as these entail judgments that are more than usually arbitrary. No health system is the product of anything like ‘intelligent design’; health systems are not ‘systematic’ a priori, though systemic features emerge as the effect of repeated interventions and adjustments over time. A health system is not a machine but a piece of software, always subject to bugs and fixes and then more occasionally to revisions of its source code and operating systems.

Health-Care Provision

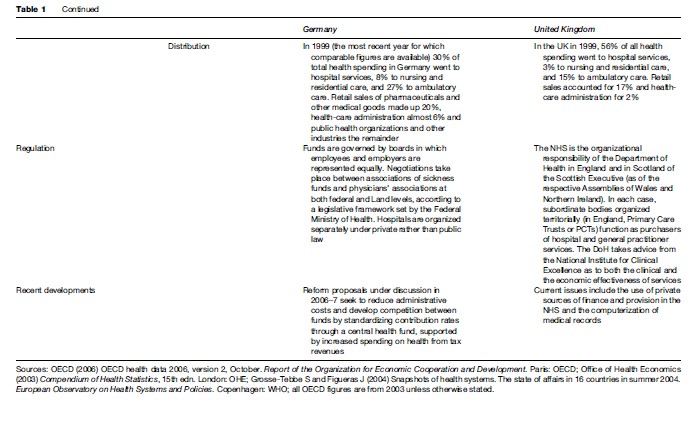

To describe health-care provision means describing the social roles and identities, both individual and collective, of patients and doctors and the organizational setting in which encounters between them take place (see Table 2).

Hospitals

At the center of the system of medical care and provision is the hospital. Hospitals may be owned by the state, whether local, regional, or national. Many are run as charitable, nonprofit organizations, and some are commercial organizations run for profit. The organizational structure of the hospital is an uneasy combination of different lines of authority, one professional and scientific, one administrative and managerial. Managerial capacity is more developed in some countries than others.

Germany and Austria have more than eight hospital beds per 1000 population, twice as many as Denmark, Norway, Spain, and the UK (OECD, 2006). National sources indicate that, in most countries, most beds are in publicly owned institutions: 65% in France, up to 80% in Italy, 85% in Norway, and more than 90% in the UK, though only 14% in the Netherlands. In most countries, too, this figure has declined since 1970. Private hospitals, both nonprofit and for-profit, tend to be smaller than publicly owned ones. In most countries, the private hospital sector is dominated by nonprofit hospitals, in terms of both the number of facilities and the number of beds.

In the course of the 1980s and 1990s, hospital capacity (measured in numbers of beds) decreased across OECD countries. Hospital activity, however, intensified, as new treatments made possible higher rates of admission for shorter periods of time. The average length of a hospital stay in western Europe is now about a week.

Primary Care

The corollary of shorter hospital stays is that, across systems, greater emphasis is being placed on primary care (though what is understood by this term differs markedly across countries too). Again, new drugs and surgical techniques, often linked to new managerial incentives, have made it possible to unbundle a proportion of what were formerly hospital procedures into ambulatory and home care. The role of the general practitioner (GP) in the UK’s NHS and the sharp distinction made there between generalist local practice and specialist hospital treatment make it the system most strongly oriented to primary care (Macinko et al., 2003). In general, coordination functions of primary care, such as gatekeeping and referral, are more strongly developed in national health services than social insurance systems, and have increased with recent reforms. In insurance-based systems, in which GPs and specialists tend to be in direct competition in local practice, the gap between the rhetoric and the reality of primary care is much more marked (Rico et al., 2003).

Meanwhile, it is arguable that many of the original activities of the general practitioner are shifting to other agencies and professionals as well as to self-help groups and patients themselves. These activities include continuing, family-oriented care from birth to death, counseling, health-related information and advice, and support and guidance in navigating the medical system as a whole.

Health Employment

Health care remains labor and technology-intensive. The density of health employment in western Europe (the number of persons employed or self-employed in health services per thousand population) ranges from 20 or lower in Italy, Spain, and Portugal to 33 in France and the UK and to 46 in Germany. Across countries, this figure has risen substantially since 1970, and in some countries more than doubled. Reflecting the distribution of health labor, most countries have three to four times as many nurses as doctors.

The number of practicing physicians is highest in Italy and Greece at 4.1 and 4.7 per thousand population respectively and lowest in the United Kingdom (2.2). In most western European countries, this figure varies between 3 and 3.5 per thousand. More doctors tend to be specialists than general practitioners (only Belgium has more GPs than specialists), not least because of the higher earnings that specialists attract. In most countries, specialists work either in hospitals or in independent local practice (in the UK, almost all specialists work in hospitals). Across countries, almost all general practitioners work in local practice.

In 2002–3, Belgium had 30 scanners per million population, Italy 24, Germany 15, France 8, and the UK 7. Such differences may reflect different styles of medical practice, but also testify to the greater capacity of governments in some systems to counteract professional demand for new equipment and the costs it incurs.

Patients

As we observed at the outset of this survey, almost all of the inhabitants of western European countries are entitled to health care, goods, and services under public programs. A principal, if limited, exception is Germany, where membership in a statutory health insurance scheme is mandatory up to a certain earnings ceiling; the self-employed, civil servants (for whom the state covers half of their treatment costs), and high-earning employees are deemed capable of making arrangements of their own, either in public or private schemes. Until 2006 in the Netherlands, similarly, three-quarters of the population held mandatory sickness insurance; since then, all residents have been required to hold basic coverage with the insurer of their choice, public or private.

Although patients across Europe are guaranteed access to health care, this guarantee is met in different ways. In national health services, entitlement to health care is a function of citizenship or residence; in social insurance systems, it is a right earned by financial contribution to a fund. It is notable that almost everywhere patient entitlement is to consult a doctor: it is not to treatment as such, which remains at the doctor’s discretion. This discretion is limited at the margins by attempts in some countries to restrict the availability of new treatments according to evidence of their efficacy (see the section titled ‘Regulation’ below).

At the same time, in some countries and as with other areas of welfare and public service provision, such as transport and housing, a revised conception of the citizen as consumer is beginning to take hold, implying that the conception of provision according to need is changing to one more responsive to demand. What this means, however, and what difference it makes in practice are uncertain. In the UK, for example, patients’ rights to choose (and change) the doctor with whom they are registered are now specified more clearly, but evidence of how many do so and for what reason is patchy. It does seem that doctors are more likely to consult patients about which secondary services they would prefer being referred to. In other countries, attempts to give local practitioners a gatekeeping function would restrict what is currently a much greater freedom of choice. Since 1997, in Germany, members of the statutory health insurance scheme have been given new freedom to choose between funds. At the same time, even though a greater proportion of the high-earning, low-risk population has been newly entitled to exit the statutory scheme for private insurers, the rate of coverage of the statutory scheme has remained broadly constant.

The available data suggest that, in most parts of western Europe, users are either ‘fairly’ or ‘very’ satisfied with their health systems. The clear exception is southern Europe, where the proportion satisfied is everywhere less than half. Most popular seem to be those systems with higher levels of funding and ready access to specialists. Meanwhile, different systems afford citizens, patients, and the insured different opportunities to participate in decision making about the conditions under which their health care is provided and paid for. Across systems, perhaps the key locus of decision making is the consulting room, where the authority of the doctor remains preeminent. In social insurance systems, meanwhile, fund members elect their governing boards, though in practice participation in such elections is low and fund decisions are effectively made by professional managers. In different countries, different levels of organization, including district and regional health authorities and national regulatory bodies, are advised by patient representatives in various ways. More radically, perhaps, in most countries patients who can afford to do so may exit public arrangements for health-care financing and provision to seek private sector alternatives. Some few patients, similarly, cross national boundaries in pursuit of quicker, cheaper, or better quality health care.

Finance

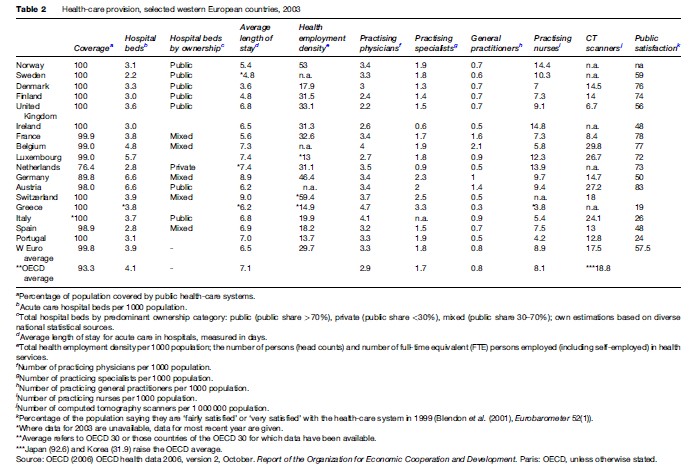

In 2003, western European countries spent between 7 and 11% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on health care (see Table 3). Switzerland spent the most, followed by Germany, Greece, France, Belgium, and Norway, all spending more than 10%; for the most part, these countries have the larger social insurance systems. The exceptions are Norway, with its exceptional resources of its oil wealth, and Greece, to which we return later. The UK, Spain, Luxemburg, Finland, and Ireland, all with large national health services, spent significantly less, between 7 and 8% of GDP.

Health financing in western Europe is broadly derived from general taxation, social insurance, private insurance, and out-of-pocket payments in different proportions. In Denmark, Sweden, and the UK it comes overwhelmingly (more than 80%) from taxation. Italy, Spain, and Portugal, the other countries with a NHS, also raise between two-thirds and three-quarters (65 to 75%) of their health spending from taxation. France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxemburg finance health care mostly (between three-fifths and three-quarters, 60 to 75%) through social insurance, as we would expect from our classifications.

It is of more than passing significance that health systems are classified first according to their principal finance mechanisms, from which much else seems to follow. However, differences among them are not always or necessarily as great as they seem. The way in which social insurance contributions are levied, for example, makes them much like a form of payroll taxation – contribution rates are mostly uniform, except in Germany, where individual funds set rates to cover the costs of their respective memberships. In contrast, tax-based systems might be thought of as simply a different way of insuring against risk. Meanwhile, most systems depend on a combination of payment mechanisms: even the most public forms of national health service allow for the private insurance of certain individuals in certain circumstances. Almost all individuals, too, make direct, out-of-pocket payments for ad hoc goods and services, as well as, in some systems, to partially finance their basic care.

On average, less than 10% of health financing in western European countries comes from private health insurance. In some countries, such as Norway and Sweden, because the entire population is fully covered for almost all health care, the number of people with private health insurance is negligible. In many other countries, private health insurance serves a variety of functions (Colombo and Tapay, 2004). For some people, such as those not required to join the statutory scheme in Germany, it is their primary source of coverage. In France, most people have some form of complementary private insurance for that portion of medical bills not covered by public schemes. In the UK, the 10% of the population with private health insurance effectively has duplicate coverage, because private insurance does not exempt or exclude them either from contributing (through general taxation) or being entitled to NHS services. It may provide access to different providers or levels of service or to some additional services not provided by the NHS.

Out-of-pocket spending – meaning direct spending by private households, either as whole or partial payment for services or medicines – makes up the larger part of nonpublic spending on health, between 10 and 25% all health spending across countries. It tends to be higher in southern Europe and is remarkably high in Greece, where it comprises 45% of all health finance. Greece is otherwise interesting for its even distribution of revenue raised from taxation (27.9%) and social insurance (25.7%), reflecting the coexistence of its NHS with compulsory social insurance and private health insurance systems.

On average, health spending (as a proportion of GDP) has grown just less than 2% per annum across countries since 1970, though this figure masks differences in rates of change over time and between countries. In general, growth in health spending reflects growth in national wealth, which explains why it has increased faster in southern Europe than elsewhere. Relatively restricted growth in the national health services of northern Europe (except in Norway, above) reflects the greater capacity of governments to control health spending there (by controlling the allocation of tax revenue to health care). This begs interesting comparative questions about how and why health systems are regulated or governed.

Regulation

The health-care state in Europe has three ‘faces’: it is at once a welfare state, an industrial capitalist state, and a liberal democratic state (Moran, 1995). This is to say that European governments are now, in effect, politically obliged to ensure access to health care for all their citizens. However, they also hold responsibility for the management of their economies, which means variously providing a healthy workforce, supporting biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries as well as the service economy of health care, and doing all of this without committing resources to such an extent or in such a way that other parts of the economy are undermined. Meanwhile, the decisions they face and make are subject to often intense pressure and scrutiny in the media as well as by political parties and pressure groups representing the often competing interests of industry, doctors and other health service workers, and, of course, citizens and patients. As each of these sets of demands has increased – as health care has become more complex, sophisticated, and expensive; as national economies have been exposed to global pressures; and as public expectations of quality, transparency, and accountability have increased – so has the need to reconcile them been intensified. Together, and in different ways in different countries, these pressures have prompted what has sometimes been called an ‘epidemic’ of healthcare reform in European countries, which has taken place over the last two decades.

The regulation of health care in Europe is a story of the slow establishment of public authority and then the increasing use of market-like, corporate, and managerial instruments to supplement it. Accompanying these changes have been both extensive and intensive debate of the limits of public responsibility and authority, the scope of the market, and the appropriateness and effectiveness of self-regulation on the part of doctors, hospitals, and insurance funds (Rothgang et al., 2005). It has also meant reconsidering the levels at which regulatory authority should be held, whether central, regional, local, or even supranational.

Different kinds of health system typically face different kinds of problem. In social insurance systems, the existence of multiple payers and multiple providers, linked with the free access of patients to specialist services, makes cost control difficult. At the same time, the standard assumption that insurance contributions are made from earnings makes for structural difficulty when rates of unemployment are high. In an equal and opposite way, tax-based national health services are much better able to control costs and to match spending with revenue, but face problems in ensuring ready access to high-quality specialist care. Sector-specific problems such as these have forced increased attention to the way in which different systems are organized and managed.

The classic form of the NHS is an integrated administrative system of finance and provision, organized hierarchically from the center. Likewise, social insurance systems turn primarily on lateral, network relationships among payers and providers. Interestingly, to correct their respective weaknesses, both types of system have sought to introduce market-like competitive elements to relationships among different actors and agencies. In the English NHS, for example, this has meant separating the formerly integrated functions of purchasing and provision, as well as raising additional investment funding from private sources. In the German social insurance system, in which purchasing and provision were already separated, contracts between funds and institutional providers have been made more flexible, and fund members have been given a greater degree of choice as to which fund they join. Similarly, in some countries, privatization trends seem to have accelerated recently. In Norway, the private share of hospital provision has increased significantly; in the Netherlands, for-profit providers now have access to a sector that used to be reserved for nonprofits. In the UK, the small private sector is now dominated by for-profit providers, whereas in Germany, the private, for profit hospital sector is expected to grow substantially.

All of this seems to mean that mixed forms of provision and finance make for mixed modes and instruments of regulation. Markets, hierarchies, and networks may be found in almost all systems in different forms, each complemented by the others. Fundamentally, nevertheless, the manipulation of these relationships and the instruments by which they are governed entails an increased assumption of public authority. Sometimes this has been by means of large-scale legislative reform, but as often as not it has come as a result of a creeping extension of the power of regulatory agencies (Hacker, 2004). The health systems of western Europe remain highly bounded by the legal, administrative and political authority of the state.

However, little changes in health systems without affecting doctors, directly or indirectly. Governments’ attempts to steer systems in new directions have invariably entailed new regulation of the medical professions. This increased regulation has meant combining more political accountability at the national level with closer and more detailed management and accounting of the medical labor process (Dubois et al., 2006). One of the most significant levers that government has over the professions is through state control of higher education, and another is the often nationwide contract for services to be delivered both through national health services and social insurance schemes. In addition, in several countries, state-sponsored bodies for quality assurance and standard setting, as well as clinical guidelines and performance indicators, have been established. A pertinent side effect of such developments is that other professions, notably nursing, have become less subordinate to medicine and more directly accountable to government.

Nevertheless, because their monopoly of medical knowledge affords doctors something like a veto position in health reform, government is invariably forced to negotiate regulatory change with professional providers, such that new regulation may often serve to reinforce the basis of professional power (Kuhlmann and Burau, in press). What counts as evidence-based medicine, for example, is decided by doctors themselves. And though scientific knowledge is effectively international, medical power remains embedded in national institutional frameworks.

Meanwhile, the regulatory authority of the state has been, at least in part, stretched and redistributed vertically. For the responsibilities assumed by national governments in the process of universalizing access to health care in Europe in the mid to late twentieth century are shared to some extent with regional administrations and, albeit haltingly, with the Commission of the European Union (EU).

Even the most centralized states, such as England and France, are divided into regions and districts for administrative purposes. In the UK, political authority and policy competence in some areas were devolved to Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales, albeit unevenly, in 1999. Similarly, in Spain, different regions hold different degrees of responsibility for health care. Legislative clarification of federal responsibilities in Italy has made regional governments almost wholly responsible for health administration, whereas county council mergers in Sweden have increased their capacity to carry out similar tasks. The subnational government of health care makes for possible tension between regional autonomy and a concern, most strongly expressed in national health services, for universalism and equity at the national level. In Germany, one side effect of the unification of East and West in 1990, which increased the number of regional states from 11 to 16, was to increase the relative authority of the center.

At the supranational level, the EC has no direct responsibility for the provision and finance of health care as such and nor has it sought any. Its Directorate General for Health and Consumer Protection remains a relatively weak member of Europe’s international health policy community, though it has taken more direct interest in aspects of public health, such as by establishing a European Centre for Disease Protection and Control and by increasing restrictions on tobacco advertising. Nevertheless, legislative provisions meant to guarantee the free movement of labor, capital, goods, and services in the single market have inevitably affected one of the largest areas of European economic activity, the health sector (Greer, 2006). Beginning in 1998, for example, a series of European Court of Justice decisions have effectively guaranteed the right of citizens of one European member state to use health services provided in another, whereas labor legislation such as the Working Time Directive, has begun to change the way trainee doctors’ work is organized in some countries. By the same token, insurance and some hospital providers are increasingly operating across national borders. However, use of the EU’s ‘open method of coordination,’ a way of setting and achieving common standards across countries by means of benchmarking, information exchange, and peer review, is less developed in health than in other areas of European public policy. ‘Regulation by comparison’ has resulted, if at all, from the benchmarking and target-setting activity of other international agencies such as WHO.

Regulation And Convergence

For much of the 20th century, that period in which most European countries introduced, expanded, and more or less completed the public guarantee of access to health care, what was notable was the range and variety of ways and means by which they did so. By the end of the period, however, the structural similarities noted at the outset of this survey seemed to be increasing markedly (Mechanic and Rochefort, 1996): the countries of western Europe had reached comparable levels of economic development, with similar demographic structures, family patterns, and cultural formations. Differences among their political systems had narrowed markedly too: all are now forms of parliamentary democracy. At the same time, their policy choices have become subject to the common constraints set by EU membership and the pressures of an increasingly global economy. It is arguable, too, that health policymakers are commonly inspired by the increasing availability of information they have about each other. What has this meant for the health systems of western Europe? Have they, should they, might they become all more or less the same?

As we address these questions, we should be clear about what they mean. Convergence can refer to a diminution of dispersion, to ‘catch-up’ processes, or to common movement toward a single model. The first two of these require quantitative data and are used for assessing levels of finance and service provision. The regulation dimension is more qualitative and relies on conceptual definition and judgment, which may be much of the reason why it is so much debated.

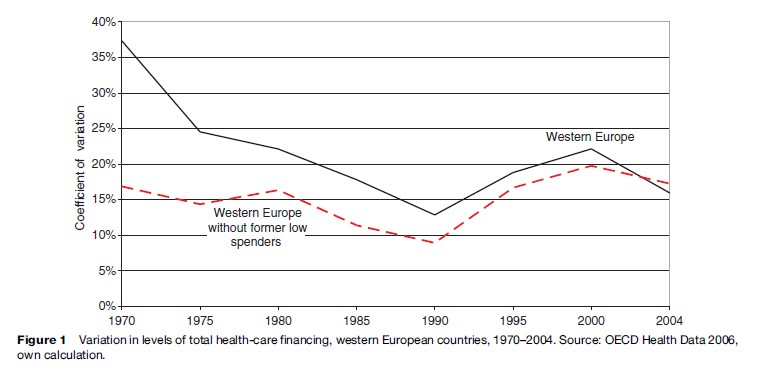

With respect to levels of service provision across countries, measured either by numbers of hospital beds and/or by rates of health employment, findings point to continuing and perhaps even increasing divergence among Western European countries (Wendt et al., 2005). Meanwhile, the EU proclaims economic convergence as a major policy goal and has successfully implemented instruments to promote it. Because national wealth is a major determinant of health-care expenditure, economic convergence tends to foster catch-up processes in healthcare spending. Figure 1 shows how the coefficient of variation of total health spending has declined since 1970.

However, looking at the data excluding those countries that started the period with health spending of less than 4% GDP (Portugal, Spain, Belgium, and Luxembourg) shows that there is much more limited convergence among the other countries. It is the catch-up process of these former low spenders that drives convergence in total health-care financing. Patterns of spending, meanwhile, tend to converge only in times of prosperity as in the early 1970s. As we have noted, because NHS systems are predicated on more powerful mechanisms of controlling costs, public spending on health tends to diverge as soon as different countries experience financial strain.

Evidence of convergence in health-care provision and finance, then, seems mixed. In respect of regulation, studies using large country samples generally seem to highlight common trends, whereas in-depth case studies provide rather more differentiated findings. In social insurance systems, based on the self-administration of networks of corporate actors, elements of both hierarchy and competition have been introduced and increased. In national health services, predicated on public authority, market and network mechanisms now complement the regulatory structure. What seems to be a blurring of regimes (Goodin and Rein, 2001), however, is not the same as convergence on a single model. Many systems are now characterized more readily as mixed types, but the nature of the mix differs among countries. As analysts seek to describe and explain these different mixes, policymakers continue to look for the right one.

Bibliography:

- Blendon RJ, Kim M, and Benson JM (2001) ‘The public versus the World Health Organization on health system performance. Health Affairs 20(3): 10–20.

- Colombo F and Tapay N (2004) Private health insurance in OECD countries. The benefits and costs for individuals and health systems. OECD Health Working Papers 15. Paris, France: OECD.

- Dubois C-A, Dixon A, and McKee M (2006) Reshaping the regulation of the workforce in European health care systems. In: Dubois C-A, McKee M and Nolte E (eds.) Human Resources for Health in Europe. London: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Freeman R (2000) The Politics of Health in Europe. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Goodin RE and Rein M (2001) Regimes on pillars: Alternative welfare state logics and dynamics. Public Administration 79(3/4): 769–801.

- Greer S (2008) Choosing paths in European Union health policy: A political analysis of a critical juncture. Journal of European Social Policy 18(3).

- Grosse-Tebbe S and Figueras J (2004) Snapshots of health systems. The state of affairs in 16 countries in summer 2004. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO.

- Hacker JS (2004) Dismantling the health care state? Political institutions, public policies and the comparative politics of health reform. British Journal of Political Science 34(4): 693–724.

- Kuhlmann E and Burau V (in press) The ‘‘healthcare state’’ in transition: National and international contexts of changing professional governance. Special Issue: Professional Work in Europe: Concepts, Theories and Methodologies. European Societies.

- Macinko J, Starfield B, and Shi L (2003) The contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970–1998. Health Services Research 38(3): 831–865.

- Marmor TR, Freeman R, and Okma K (eds.) (2008, forthcoming) Learning from Comparison in Health Policy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Mechanic D and Rochefort D (1996) Comparative medical systems. Annual Review of Sociology 22: 239–270.

- Moran M (1995) Three faces of the health care state. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 20(3): 767–781.

- OECD (2006) OECD health data 2006, version 2, October. Report of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Paris, France: OECD.

- Office of Health Economics (2003) Compendium of Health Statistics, 15th edn. London: OHE.

- Rico A, Saltman RB, and Boerma WGW (2003) Organizational restructuring in European health systems: the role of primary care. Social Policy and Administration 37(6): 592–608.

- Rothgang H, Cacace M, Grimmeisen S, and Wendt C (2005) The changing role of the state in healthcare systems. European Review 13(1): 187–212.

- Wendt C, Grimmeisen S, and Rothgang H (2005) Convergence or divergence of OECD health care systems. In: Marx I (ed.) International Cooperation in Social Security. How to Cope with Globalisation? Antwerp, Belgium: Intersentia.

- Blank RH and Burau V (2007) Comparative Health Policy, 2nd edn. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dixon A and Mossialos E (2001) Funding Health Care in Europe: Recent Experiences. In: Harrison T and Appleby J (eds.) Health Care UK. London: Kings Fund.

- Johnson T, Larkin G and Saks M (eds.) (1995) Health Professions and the State in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Maarse H (ed.) (2004) Privatisation in European Health Care: A Comparative Analysis in Eight Countries. Maarssen, the Netherlands: Elsevier.

- Marmor TR, Freeman R, and Okma K (2005) Comparative perspectives and policy learning in the world of health care. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis 7(4): 331–348.

- Moran M (1999) Governing the Health Care State. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Moran M and Wood B (1993) States, Regulation and the Medical Profession. London: Open University Press.

- Mossialos E and Le Grand J (1999) Health Care and Cost Containment in the European Union. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

- Oliver AJ, Mossialos E, and Maynard A (2005) Special Issue: Analysing the Impact of Health System Changes in the EU Member States. Health Economics 14: S1–S263.

- Randall E (2000) The European Union and Health Policy. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

- WHO (2000) World Health Report 2000. Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- WHO (2005) National Policy on Traditional Medicine and Regulation of Herbal Medicines. Report of a WHO Global Survey. Geneva, Switerzland: WHO.

- http://www.oecd.org – Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- http://www.euro.who.int – WHO European Observatory on Health Systems.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.