This sample Tobacco Harm Minimization Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

Tobacco is the second leading cause of death in the world today, currently responsible for about 5 million deaths each year. If current tobacco use trends continue, it will cause some 10 million deaths each year by 2020 and over 1 billion deaths combined in the twenty-first century.

Manufactured cigarettes are the predominant form of tobacco used worldwide and by far and away the most lethal type of tobacco use. In fact, one could argue that eliminating cigarettes would be a logical and particularly potent harm reduction intervention. In 2004, manufactured cigarettes accounted for 95% of total smoked tobacco sales, with cigars and other smoked tobacco such as roll-your-own cigarettes, pipes, bidis, and kreteks accounting for the remainder. Oral smokeless tobacco is common in Southeast Asia and regionally is popular in parts of Europe (Sweden) and the United States.

Despite the devastating health consequences caused by tobacco use, tobacco remains a valued economic commodity worldwide, making it a challenge for governments to control. In 2002, the world market for tobacco products was worth some US$354 billion. In developed countries tobacco sales are slowly losing volume due to health concerns and price rises, while developing countries are gaining volume due to demographics. In 2002 the four largest markets – China, the United States, Japan, and Russia – accounted for 52% of global tobacco consumption, with China alone accounting for almost one-third of the global market.

Between 2002 and 2004, global cigarette volume declined for the first time, driven largely by sharp reductions in cigarette sales in Western Europe and the United States, resulting from a combination of higher cigarette prices, increasing health awareness, and implementation of smoke-free laws. In the United States, litigation has also been an important factor affecting cigarette prices. For example, the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) of 1998, obliged tobacco companies to contribute billions annually in payments to states for health-care claims in return for litigation relief. Because of the decline in the cigarette market in Western Europe and the United States, the tobacco industry has begun to concentrate its efforts on emerging new markets in low and middle-income countries such as Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and the African continent. Over the next decade the factors that are likely to influence trends in tobacco consumption will be price competition resulting from the dismantling of cigarette monopolies, the growth in contraband (nonduty-paid) cigarettes, and legislation altering the marketing and use of tobacco products.

Historically, efforts to prohibit the sale of tobacco products have not worked. The first recorded prohibition against tobacco use resulted from a clash between Peruvian native and Christian religious customs which led to a 1586 Papal decree declaring it a sin for any priest to use tobacco before celebrating or administering communion. In the early 1600s King James I of England attempted to discourage the use of tobacco by taxing it, the czar of Russia exiled tobacco users to Siberia, and in China, those caught selling tobacco were executed. In July 2003, the Kingdom of Bhutan in the Himalayas banned tobacco sales, mainly for religious reasons. However, it is unlikely that many other countries will follow Bhutan’s example, since the economic benefits of tobacco are perceived to be too large to give it up. Instead, most governments have adopted a harm minimization approach to tobacco control.

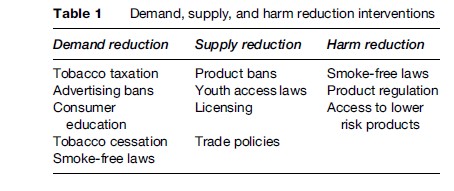

Harm minimization, in contrast to prohibition, accepts as a basic premise that tobacco use will continue to be part of society and that eradication is not practical. Harm minimization for tobacco control comprises programs and policies designed to accomplish three goals: (1) reduce the demand for tobacco; (2) reduce the supply of tobacco; and (3) reduce the harm caused by tobacco products. Demand reduction interventions have the goal of reducing consumer interest in using tobacco, while supply reduction attempts to reduce tobacco use by limiting the supply of tobacco to the population. Harm reduction assumes that people will continue to use tobacco and thus seeks to minimize the harm caused by using tobacco products by altering their potential to cause disease and disability to both users and nonusers. Table 1 gives examples of demand, supply, and harm reduction interventions.

The remaining sections of this research paper describe the rationale and evidence for the effectiveness of various demand, supply, and harm reduction interventions intended to minimize the harm caused by tobacco in society.

Demand Reduction

Demand reduction programs and policies have the goal of reducing consumer interest in using tobacco or assisting those who use tobacco to quit. One of the most straightforward ways to influence consumer demand for tobacco is through taxation.

Tobacco Taxation

The rise in the taxes and duties applied to cigarettes has been the main driver of market value growth over the past decade. The average tax per pack in Western Europe is more than four times that in Eastern Europe and Africa and the Middle East. In Western Europe, the huge tax discrepancies on a pack of 20, varying between $6.80 (USD) in Norway and $5.90 (USD) in the United Kingdom to $1.47 (USD) in Spain, suggest the future scope for tax revenue growth. Price has been a key global market driver over the years between 1998 and 2002. Since 1998 prices have nearly doubled in the United States as a result of higher taxation and price increases by the manufacturers to recoup the costs of the MSA. However, cigarette prices in the United States at $3.85 (USD) for a pack of 20 in 2003 were still well below the levels to be found in the United Kingdom, which were at $7.47 (USD).

Studies indicate that taxes on tobacco products, usually in the form of an excise tax, are passed directly onto the consumer. Economists use estimates of the price elasticity of demand to quantify the impact of a change in price on consumption. Formally, the price elasticity of demand is defined as the percentage change in consumption resulting from a 1% increase in price. While a relatively wide range of estimates has been produced for the price elasticity of demand for cigarettes, most of the estimates from the high-income countries tend to fall in the relatively narrow range from 0.25 to 0.50. Thus, a cigarette price rise by 10% translates into a reduction in cigarette smoking by between 2.5 and 5%. Several studies have documented that those with less disposable income are more sensitive to tobacco price changes. For example, some estimates imply that teen smokers are up to three times more sensitive to price than adult smokers.

While tobacco taxation is a fairly direct means of influencing consumption it can also have adverse effects that actually do harm to tobacco control efforts. For example, in parts of Africa (e.g., Malawi) and rural China, government officials have become so dependent on tobacco sales there is little incentive for them to support programs and policies that would discourage people from using tobacco. Even in high-income countries, tobacco taxation is a double-edged sword, preventing enactment of truly effective tobacco control policies for fear that tax revenues might decline. Also higher taxes on tobacco products brings with it the real threat of illegal enterprises that often crop up to take advantage of opportunities for tax evasion. Cigarettes are the world’s most widely smuggled legal consumer product (see later section titled ‘Supply Reduction’).

Tobacco taxes are not the only way to influence the price of tobacco products. For example, policies that impact price marketing of tobacco products such as rules dictating minimum package size, banning product sampling, or restricting use of coupons and price promotions (e.g., buy one, get one free) all can impact consumer demand. Differential tax policies on different forms of tobacco can also influence demand. For example, in Western Europe the impact of rising taxes on cigarettes may have caused some smokers to switch to roll-your-own cigarettes, since loose tobacco is taxed at a lower rate, making it a cheaper substitute for factory-made cigarettes.

Advertising Bans

Research has also shown that awareness of tobacco advertising and participation in tobacco promotions are associated with smoking status. For example, several studies have found that young people’s future smoking behavior is predicted by their awareness and involvement in tobacco advertising, sponsorship, and merchandising. Policy makers have responded to the public health threat posed by tobacco advertising and promotional activities by introducing regulatory policies to control the industry’s marketing. The policy options that have been proposed for the control of tobacco advertising have included limitations on the content of advertisements, restrictions on the placement of advertising, restrictions on the time that cigarette advertising can be placed on broadcast media, total advertising bans in one or more media, counter advertising, and the taxation of advertising. A recent study by the World Bank concluded that a comprehensive set of tobacco advertising bans can reduce tobacco consumption, but that a limited set of advertising bans will have little or no effect.

Consumer Education

Declining cigarette consumption in developed nations corresponds directly to increased public awareness of the dangers of tobacco use. The extent to which smokers understand the magnitude of these health risks has a strong influence on their smoking behavior. For example, in developed countries the level of news media coverage of smoking and health from 1950 to the early 1980s mirrors population trends in awareness about smoking as a cause of lung cancer and rates of smoking cessation.

At present, most smokers concede that tobacco use is a health risk; however, important gaps remain in their understanding of these risks and the level of knowledge is not uniform across the globe. Even in high-income countries with long histories of progressive tobacco control efforts, significant proportions of smokers continue to underestimate the serious risks of smoking, including heart disease, stroke, and respiratory disease, as well as the risks of secondhand smoke. Communicating the health effects of smoking remains a primary goal of tobacco control policy.

Pack Warnings

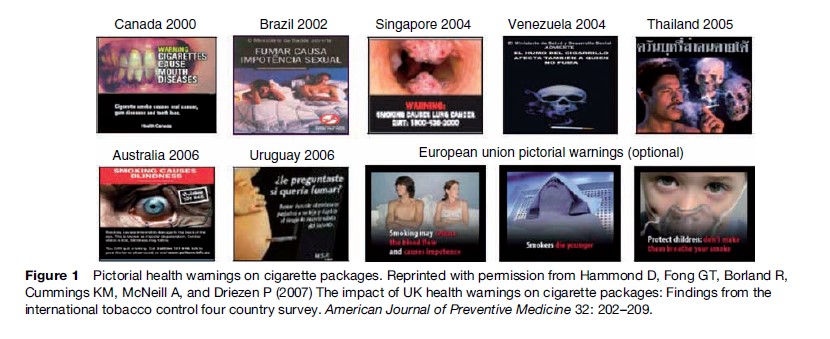

The provision of health warnings and/or product information on tobacco packages is an important means of informing consumers about the health risks of smoking as a first step toward changing behavior. Nearly all countries throughout the world require package warning labels on cigarettes, although the content and size of the warnings vary widely. Canada, Brazil, Singapore, Thailand, and Venezuela have recently introduced picture-based warnings that cover at least half of cigarette packages (Figure 1). In addition, the European Union (EU) has created an ‘optional’ list of pictorial warnings for its member states, although to date, only Belgium has committed to implementing these warnings. Research indicates that warning labels on cigarette packs are a salient means of communicating with smokers, although their effectiveness depends upon their size and comprehensiveness: obscure text-only messages are unlikely to be noticed, whereas large pictorial warnings are effective in engaging smokers and promoting message recall. A recent study comparing reports of adult smokers in Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, and the United States found that two thirds of smokers cited cigarette packages as a source of health information, with a significant association between the strength of package health warnings and the likelihood of citing packages as a source of health information. In short, larger, more comprehensive warnings were more likely to be cited as a source of health information.

Not only were health warnings self-identified as an important source of health information about smoking; they were also an effective means of communicating that health information. The results provide evidence at both the individual and country-level that health warnings on cigarette packages are strongly associated with health knowledge. Health knowledge was found to be strongly associated with intentions to quit among smokers in all four countries. This finding supports previous evidence that although awareness and acceptance of the health risks of smoking may not be a sufficient condition for quitting, it is likely a necessary one for most smokers and serves as an important source of motivation.

Countermarketing

Antitobacco mass media campaigns, when adequately funded, can be effective in reducing cigarette consumption. The first large-scale national counter advertising campaign to educate the public about the health risks of tobacco use occurred in the United States between 1967 and 1970 when the Federal Communications Commission required licensees who broadcast cigarette commercials to provide free media time for antismoking public service announcementsunder the Fairness Doctrine. Between 1967 and 1970 cigarette consumption in the United States dropped at a much faster rate than during the period immediately before or after the time when the Fairness Doctrine antismoking campaign was operational. Subsequent studies in several other countries have confirmed that adequately resourced mass-media campaigns that have the objective of educating the public about the risks of smoking lead to reductions in cigarette consumption.

Tobacco Cessation

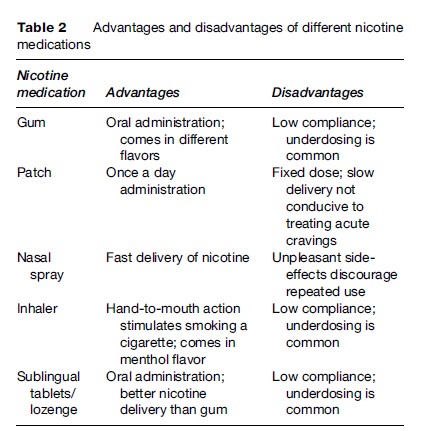

Historically, the vast majority (>90%) of former smokers have reported that they stopped smoking without receiving formal assistance or help from anyone. However, in high-income countries this statistic is changing with the introduction and widespread availability of effective drug therapies to help smokers alleviate withdrawal symptoms commonly associated with cessation. Two-milligram, prescription-only nicotine gum was first introduced in the early 1980s and was followed by prescription-only nicotine patches introduced in the early 1990s. Since then, a wide variety of nicotine medication formulations including 4-mg nicotine gum, a nasal spray inhaler, and lozenge have been marketed. Table 2 describes the advantages and disadvantages of various nicotine medication formulations.

A recent systematic review of studies evaluating commercially available forms of nicotine replacement therapy (e.g., nicotine gum, the transdermal nicotine patch, nicotine nasal spray, nicotine inhaler, and nicotine sublingual tablets/lozenges) concluded that these treatments increase quit rates approximately 1.5to 2-fold regardless of clinical setting or treatment. Over the past decade governments have altered their policies to permit over-the-counter sale of certain nicotine medication formulations such as the gum, patch, and lozenge. Studies have suggested that this policy has increased use of nicotine medications, although the overall effect on population tobacco use remains unclear. In the United States, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, studies show that over one-third of smokers who report having made a quit attempt in the past have tried some form of nicotine (patch, gum, inhaler, nasal spray) or non-nicotine therapeutic aid (bupropion).

A number of new therapeutic approaches for treating nicotine dependence have recently been introduced (e.g., varenicline) or are under development, which could dramatically alter the way nicotine dependence is treated in the future. For example, varenicline is a new non-nicotine medication recently for sale in the United States that works by directly targeting nicotine receptors and the dopamine system. Varenicline is a selective a4b2 partial agonist developed to enhance smoking cessation by moderating symptoms of nicotine withdrawal, including reduced craving and decreased smoking satisfaction and psychological reward. Early studies suggest that varenicline may not only help with smoking cessation, but also may help prevent relapse back to smoking with extended use. Clinical trials are also underway testing a vaccine to block nicotine delivery to the brain, thereby removing the main reinforcement for smoking. The conjugated vaccine works by stimulating the immune system to produce antibodies that find and attach to nicotine molecules, making them too large to pass over the blood–brain barrier preventing delivery of nicotine to the brain. Other drugs are being investigated that either block or replace the reinforcing effects of nicotine in the brain. The high cost of these medications is likely to be a limiting factor preventing their widespread dissemination to tobacco users, especially in lowand middle-income countries. However, advancements in drug development hold considerable promise to dramatically alter how nicotine dependence is perceived and addressed in the future

Supply Reduction

Supply reduction interventions seek to control tobacco use by limiting the supply of tobacco products in the population. One of the most straightforward ways to influence the supply of tobacco is simply to ban it.

Product Bans

With nearly 1 billion tobacco users worldwide, a total prohibition on tobacco sales is not practical. However, some countries have tried to limit the sale of specific types of tobacco products, such as smokeless tobacco and high-tar cigarettes, usually with the intention of removing products perceived as particularly risky from the market. Moist snuff is banned in Australia and most parts of the EU, with the exception of Sweden. There is evidence that such prohibitions do influence the types of tobacco products people use. For example, in Sweden where snuff can be legally sold, the percentage of male cigarette smokers is low compared to other parts of Europe, whereas use of snus, a type of smokeless tobacco, is common. The opposite is true in other parts of Europe and Australia where cigarette smoking is very prevalent and use of smokeless tobacco is extremely rare. In North America, where both cigarettes and snuff are legally sold, cigarettes are used far more frequently.

Policies that attempt to limit the supply of tobacco products can have adverse consequences, such as increased smuggling and/or counterfeiting. Tax hikes as well as cross-border discrepancies in prices have fueled a growing contraband/counterfeiting cigarette market. Each year approximately 400 billion cigarettes, or one-third of all legally exported cigarettes, end up illegally smuggled across international borders. Cigarette smuggling has the effect of increasing the number of smokers by providing a less-expensive supply of cigarettes, especially for the young and the poor. Cigarette smuggling also has an indirect impact on the adoption of demand-reducing policies, such as cigarette taxation, because the threat of smuggling can discourage governments from raising cigarette and other tobacco taxes, or can lead others to reduce their taxes, resulting in lower prices than would exist in the absence of smuggling. A black market in cigarettes can also undermine efforts to limit youth access to tobacco products as the presence of smuggled cigarettes can put legitimate retailers at a competitive disadvantage, leading some to be less compliant with tobacco-control laws than they would be in the absence of competition from a black market.

Counterfeiting involves illegally manufacturing and distributing tobacco products without a license. The market for counterfeit cigarettes has grown in recent years as cigarette prices have increased and the distribution system for contraband cigarettes has expanded. For example, the sale of cigarettes over the Internet has allowed the distribution of counterfeit and low-taxed cigarettes to flourish, making it difficult for governments to block the supply of these illegal products.

Licensing And Product Tracking

Governments have attempted to limit smuggling and counterfeiting of tobacco products by creating licensing systems for manufacturers, distributors, and retailers and implementing systems to track the distribution of tobacco products from manufacturers to consumers. Increasingly, countries are adopting strong antismuggling policies that include marking cigarettes to allow better tracking and identification of smuggled products, mandatory licensing of all parties involved in cigarette distribution, chain-of-custody recordkeeping to allow for tracking of cigarettes from the factory to the final country of sale, and the elimination of duty-free sales, which has in the past served as a major source of smuggled cigarettes. Regional agreements between countries, such as those governing the EU, have begun to evolve on issues like taxation and systems for tracking the distribution of tobacco products so as to reduce incentives for smuggling and counterfeiting. In the United States, credit card companies and major private shippers have recently agreed to not accept charges for cigarettes from Internet retailers, and to not deliver cigarettes to individuals, in an effort to stem the flow of low-taxed and counterfeit cigarettes.

Trade Policies And Industry Configuration

International trade agreements can also have a major impact on the price and marketing of tobacco products. Over the past decade there has been a trend toward dismantling state-owed tobacco monopolies in favor of allowing privately owned tobacco companies to compete for market share in a country. The result of this trend has been an increased demand for tobacco fueled by lower prices and increased marketing. Monopolies still account for over 40% of world tobacco sales by volume, although over two-thirds of this volume is attributable to the Chinese monopoly. In countries with state-owned tobacco, monopolies’ import taxes typically keep foreign tobacco brands out of the market. However, China’s recent admission to the World Trade Organization has resulted in China cutting tariffs on foreign brands, dramatically reducing the price differential between local and foreign brands. The Chinese government has also changed legislation that affects the distribution of foreign cigarettes in China. Previously, retailers had been required to apply for two licenses to sell cigarettes – one for domestic products and one for foreign brands. Now, retailers need only one license to sell both local and foreign brands, which will simplify foreign firms’ access to the market. Future trends in tobacco consumption, especially in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and parts of the African continent where manufacturing monopolies remain, are likely to be influenced by trade agreements that permit private multinational tobacco corporations to enter a market and compete with state-owned tobacco companies.

Industry consolidation is another trend that is likely to influence tobacco marketing and pricing. Between 1990 and the end of 2003, there were over 50 major changes of ownership of privately owned tobacco companies. Key changes of ownership include the acquisition of RJ Reynolds’ international business by Japan Tobacco, the acquisition of Rothman’s International by BAT, and the acquisition of Reemtsma by Imperial Tobacco. The result of these acquisitions has been the creation of a smaller number of companies that control a larger share of the worldwide cigarette market, the emergence of global super-brands, and cost savings obtained through consolidation of marketing and distribution channels. The worldwide cigarette market is controlled by a handful of companies of which China National Tobacco Corporation is the largest with 32% of the cigarette sales. Philip Morris controls about 16% of worldwide cigarette sales, followed by British American Tobacco with 11%, and Japan Tobacco with roughly 7% of sales. Philip Morris has recently entered into a joint venture agreement with China National Tobacco Corporation to manufacture and market the Marlboro brand in China; Philip Morris also recently acquired Indonesia’s Sampoerna tobacco company, gaining entry into that country’s kretek and cigarette market.

Some have argued that tobacco harm minimization might benefit by moving toward, rather than away from, state-owned tobacco monopolies. Such monopolies could have a public health mandate to reduce supply and demand, and perhaps phase out tobacco sales over time.

Youth Access Laws

Most governments have policies that attempt to limit minors’ access to tobacco products. The argument for limiting tobacco sales to minors is based on the idea that children and adolescents may not be mature enough to adequately appreciate the long-term consequences of their use of tobacco. Abundant evidence illustrates that many youths who begin to use tobacco do not fully comprehend the nature of addiction and, as a result, believe that they will be able to avoid the harmful consequences of smoking by stopping smoking after a few years. Laws intended to curtail tobacco sales to minors date back decades in most countries, but enforcement of these laws varies widely across regions of the world. Moreover, the real impact of these laws on deterring youth smoking is open to debate. The real public health benefit of policies to limit youth access to tobacco may not lie so much in the direct effect on youth smoking behavior, but rather on the declarative effects of reinforcing the social norm that disapproves of tobacco use.

Harm Reduction

Harm reduction assumes that people will continue to use tobacco and thus seeks to minimize harm caused by tobacco products by altering their potential to cause disease and disability. Harm reduction interventions include smoke-free policies that serve to protect nonsmokers from breathing tobacco smoke pollution and policies to regulate tobacco products including the use of incentives that encourage tobacco users to adopt less harmful alternatives to conventional tobacco products.

Smoke-Free Environments

Policies restricting indoor smoking have a dramatic and immediate impact on reducing the levels of indoor air pollution, thereby minimizing harm to nonsmokers and smokers. Also, there are plenty of studies to show that smoke-free policies reduce smoking rates.

Where smoking is permitted it is a significant source of indoor air pollution; banning smoking indoors typically reduces exposure to fine particle air pollutants by 80–90%. While mechanical ventilation and air cleaning devices can reduce exposure to tobacco smoke pollutants, these methods are costly and are not nearly as efficient as banning indoor smoking.

Fifty years ago there were virtually no laws regulating smoking in public locations such a schools, public transportation, government buildings, elevators, and restaurants. However, as scientific studies regarding the health consequences of passive smoke exposure began to emerge in the 1980s, policies limiting where people could smoke also increased. Today, nearly all countries have laws restricting smoking in at least some public places and workplaces, and over 20 countries have adopted and implemented comprehensive smoke-free laws that prohibit smoking in virtually all public venues including bars and restaurants (Table 3). Compliance with smoke-free regulations has varied across countries and localities, but where smoking rates are declining and the population has been educated about the health risks of tobacco smoke pollution, compliance with the smoke-free policies has been high. The trend toward smoke-free indoor environments is likely to continue in the future and be an important factor influencing how people perceive tobacco use, making it less acceptable, more inconvenient, and less pleasurable, thereby discouraging uptake of smoking and encouraging cessation of smoking.

Product Regulation

Nicotine in tobacco is the primary reason why most tobacco users continue to expose themselves daily to tobacco toxins. However, historical efforts by both the tobacco industry and government regulators to reduce the harm caused by tobacco products have often ignored this fact. In some cases well-meaning, but misguided public health policies, such as the adoption of standardized product testing regimes, did more harm than good. Many smokers continued to smoke rather than quit because they were under the illusion that lower, machine-measured tar levels were equivalent to a healthier smoke. Internal industry documents now reveal that the companies were well aware of compensatory smoking, and even counted on it to retain customers who they knew were addicted to nicotine and would simply alter how they smoke to maintain their daily nicotine delivery.

We now know that so-called low-tar cigarettes do not expose smokers to less tar because smokers compensate to get their daily dose of nicotine by taking more puffs, bigger puffs, and, in some cases, smoking more cigarettes per day. Studies have confirmed that low-tar cigarettes have not altered the risk of cancer or heart disease in smokers who have switched to these products. Unfortunately, this message has not gotten across to consumers. Over the past decade there has been a global trend toward lower tar levels of cigarettes.

The birth of so-called low-tar cigarettes was a direct result of the 1964 U.S. Surgeon General’s Report, which ‘officially’ linked cigarette smoking to cancer and other diseases. Within days of the report, American Tobacco Company announced Carlton brand cigarettes, with tar and nicotine levels about one-tenth the market average at the time (2.5 mg tar, vs. an average of about 25 mg). This also marked the introduction of the ventilated filter, which changed the cigarette market, as it allowed tar and nicotine yields to be cheaply lowered, but facilitated compensatory smoking such that smokers could titrate their dose of nicotine to maintain satisfaction.

Under the misguided belief that smokers were better off smoking low-tar cigarettes, government regulators introduced standardized product-testing regimes that would allow consumers to compare the machine-measured tar yields of different cigarette brands. In 1967 the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) introduced a standardized system for machine-testing smoke yields for cigarettes. Other countries adopted the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) protocol that was essentially the same as the FTC method. Even though FTC and ISO both acknowledged that their testing schemes were flawed and underestimated the actual amount of exposure consumers might get from smoking, cigarette manufacturers used the data to market new lower tar brands and establish brand line extensions. The trend toward lower tar cigarettes, often with increasingly sophisticated filters to retain flavor and improve brand competitiveness, has continued to dominate the cigarette industry to the present day. This trend is likely to continue unless governments intervene to change it.

However, just the opposite has occurred. In 2004 the European Commission implemented new maximal values for tar (10 mg), nicotine (1 mg), and carbon monoxide (10 mg) per cigarette, as measured by machines using the ISO method. A similar policy has recently been adopted in China that issued a regulation banning the sale of cigarettes above 15 mg/stick after July 2004. Regrettably, these well-intentioned policies are flawed because cigarette manufacturers are able to easily adjust to the new standards by increasing the filter ventilation of their existing brands. Unfortunately, increased filter ventilation promotes increased smoke intake by smokers because of increased puff volumes and blocking of filter vents with lips or fingers, meaning that the standard has not made smoking less risky, although some smokers may believe this to be so.

Because cigarettes are an important cause of residential fires, some governments have recently implemented standards for cigarette ignition propensity. In 2004, New York State became the first locality in the world to mandate fire safety standards for cigarettes. In 2005, Canada became the first country to adopt a fire safety standard for cigarettes. Both the New York and Canadian laws require cigarette brands licensed for sale to meet a performance standard whereby the cigarettes self-extinguish on a standardized test. Each measurement involves placing a lit cigarette horizontally atop 10 layers of filter paper. Whether the cigarette burns to the beginning of the tipping paper (the paper covering the filter) is the outcome of interest. At least 75% of cigarettes of each tested variety should self-extinguish before reaching the tipping paper. Preliminary data from New York State suggest that the law has reduced smoking materials fires; however, what remains unknown is whether design changes engineered into the cigarette to meet the fire safety standard have altered smoking behavior in ways that might potentially lead smokers to smoke differently.

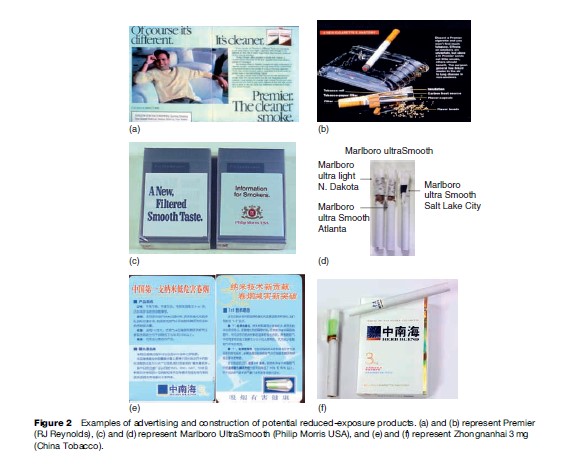

Concern over the fireproof cigarette standard raises the larger question of how product modification designed to reduce harm in one regard might inadvertently increase harm in areas that were unintended. This is exactly the concern that has been raised in recent years as cigarette manufacturers have introduced a variety of modified tobacco products with claims that they reduce exposure to selected harmful toxins found in conventional cigarettes. The first of these products to be commercially marketed was Premier, which was sold in test markets in 1988 (Figure 2(a) and 2(b)). Premier was promoted as a cleaner cigarette promising reduced secondhand smoke and exposure to other toxins found in conventional cigarettes. Premier was not really a cigarette in a conventional sense, but rather a nicotine inhaler that could satisfy the addicted smoker’s daily need for nicotine. Philip Morris has recently tested a new product called Marlboro Ultra-Smooth that boasts a high technology carbon filter (see Figure 2(c) and 2(d)). Other manufacturers have marketed similar products with claims of reduced exposure to selected smoke constituents, but questions remain about whether these products actually lower disease risk.

The marketing of reduced risk products is a sensitive area because in many countries strict laws limit making health claims so manufacturers are wary to label anything as ‘reduced harm’ for fear of litigation. However, in countries like China where the tobacco business is operated by the state, there is no such concern – China National Tobacco Corporation markets Zhongnanhai 3mg, which explicitly claims that its ‘1þ1’ nano-technology filter reduces PAHs and TSNAs in cigarette smoke (see Figure 2(e) and (f )).

Because a large component of the risk inherent in smoking comes from the thousands of combustion byproducts generated by burning paper and tobacco, simply reducing one or two selected chemicals is unlikely to alter harm. For smoked tobacco products reduced harm might be possible by requiring changes in product design that make the product less (not more) acceptable to the consumer. For example, nicotine could be eliminated, filter vents could be banned, and the use of flavorings and additives that mask the harshness of tobacco smoke could be prohibited. Each of the design alternations would make the product less acceptable to the user thereby discouraging uptake and promoting smoking cessation.

Access To Lower-Risk Products

It is ironic that the most addictive and toxic tobacco products are also the most heavily advertised and least regulated. Liberalizing government regulations so that cleaner forms of nicotine are made more acceptable and accessible to smokers compared to tobacco products has the potential to revolutionize the way the tobacco problem is perceived and dealt with in the future. The dream of a tobacco-free society is not likely to be accomplished anytime soon. Given this reality, competition to produce a less harmful alternative to smoked tobacco products would benefit the goals of public health. However, today there is really no real competition, as the cigarette cartel is dominated by a small group of companies who have little incentive to change the status quo. Competition to produce consumer-acceptable alternatives to cigarettes would be helped by educating consumers about differences in disease risk between smokeless and medicinal nicotine products and smoked tobacco. Ironically, many smokers don’t perceive much difference in health risk between smokeless tobacco products, nicotine medications, and cigarettes. Yet if all nicotine products were put on a risk continuum the actual difference between smokeless and nicotine medications would be seen as pretty minor compared to the difference in disease risk between smoked and smokeless products. Experts have estimated the risk from low nitrosamine smokeless tobacco to be approximately 90% less than that from cigarettes; the risks for medicinal nicotine are even lower compared to those from cigarettes. Government regulations such as those in the EU that prohibit the sale of smokeless tobacco while permitting the sale of smoked tobacco may be counterproductive since they contribute to confusion about the real relative risk of different smoked and smokeless tobacco products and prevent competition for the marketing of less dangerous alternatives to smoked tobacco.

Of course, the question remains as to whether smokers would be willing to abandon smoked tobacco products for a delivery system that is substantially different. However, until smokers are given enough information to allow them to choose for themselves, then the status quo will remain. Government policies could help move this process along by allowing for differential regulation of product marketing and taxation rates linked to product risk. The natural experiment in Sweden suggests that promoting smokeless tobacco can displace at least some cigarette smoking, resulting in less cancer, although it is unclear if this result in Sweden can be replicated elsewhere.

Global Tobacco Control

The global effort to reduce the burden of tobacco use has recently culminated in the creation and adoption of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which is the first global health treaty negotiated under the auspices of the World Health Organization (WHO). The FCTC is an attempt by the WHO to have all countries adopting the same rules regarding tobacco rather than having legislation varying from country to country. The treaty closed for signature on 29 June 2004; 168 countries have signed the FCTC, and 146 (as of April 2007) have become parties to the treaty. The FCTC commits countries to implement a range of tobacco harm minimization measures including increased tobacco taxes, comprehensive bans on tobacco advertising, inclusion of significantly sized health warnings on cigarette packets, protection of people from secondhand smoke, efforts to combat smuggling such as placing final destination marketing on packs, and product regulations such as the disclosure of ingredients in tobacco products and provision of treatments for tobacco addiction.

The FCTC protocols are legally binding only on countries that ratify them. Thus the onus will be on national governments to implement the FCTC and protocols. How effective the FCTC will be in slowing and eventually reversing the global tobacco epidemic will be determined by the how fully governments implement the obligations contained in the FCTC.

Bibliography:

- Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, Cummings KM, McNeill A, and Driezen P (2007) The impact of UK health warnings on cigarette packages: Findings from the international tobacco control four country survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 32: 202–209.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (1999) Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

- Cummings KM and Hyland A (2005) The effect of nicotine replacement therapy on smoking behavior. Annual Review of Public Health 26: 583–599.

- De Beyer J and Waverley-Bridgen L (2003) Tobacco Control Policy: Strategies, Successes and Setbacks. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Euromonitor International (2006) The World Market for Tobacco. http:// www.euromonitor.com (accessed September 2007).

- Ezzati M and Lopez AD (2003) Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. The Lancet 362: 847–852.

- Farrelly MC, Pechacek TF, and Chaloupka FJ (2003) The impact of tobacco control program expenditures on aggregate cigarette sales: 1981–2000. Journal of Health Economics 22: 843–849.

- IARC Working, Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic, Risks to Humans (2002) Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking vol. 83. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2002.

- Jha P and Chaloupka F (eds.) (2001) Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kluger R (1996) Ashes to Ashes: America’s Hundred-Year Cigarette War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Kozlowski LT, Strasser AA, Giovino GA, Erickson PA, and Terza JV (2001) Applying the risk/use equilibrium: Use medicinal nicotine now for harm reduction. Tobacco Control 10: 201–203.

- MacKay J and Eriksen M (2002) The Tobacco Atlas. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- National Cancer Institute (2001) Risks Associated with Smoking Cigarettes with Low Machine-Measured Yields of Tar and Nicotine. Smoking and Tobacco Control. Monograph 13. NIH Publication No. 02–5074. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, and National Institutes of Health.

- Shafey O, Dolwick S, and Guindon GE (2003) Tobacco Control Country Profiles, 2nd edn. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

- Stratton K, Shetty P, Wallace R, and Bondurant S (eds.) (2001) Clearing the Smoke: Assessing the Science Base for Tobacco Harm Reduction. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- WHO (2003) World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. http://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/ download/en (accessed September 2007).

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.