This sample Maternal Health Services Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Primarily, maternal health services aim to prevent morbidity and mortality in both the mother and the child and to promote health and well-being of pregnant women and their unborn babies. They should also provide a range of services and information allowing women to make informed choices regarding their health care in pregnancy and childbirth. Strictly speaking, maternal health services cover the period from conception to 42 days after the end of the pregnancy but ideally also provide prepregnancy counseling and advice. This research paper attempts to describe a global picture of maternal health services relevant to a public health practitioner. Although some issues, such as equity and access to health care, are universal, others, such as female genital cutting and rising cesarean section rates, are specific to certain cultures.

Epidemiology

As the primary purpose of maternal health services is to prevent maternal mortality and morbidity, it is useful to clarify the meaning of these terms at the beginning.

What Is A Maternal Death?

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (WHO, 1992) gives the definition of maternal death as:

The death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the site of the pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.

Measures Of Maternal Mortality

There are three common measures of maternal mortality – maternal mortality ratio, maternal mortality rate, and lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy-related causes. Each of these measures relates to a specific group of women and takes into account different variables.

- The maternal mortality ratio is the number of maternal deaths per 100 000 live births calculated in a year. It represents the risk associated with each pregnancy, that is, the obstetric risk.

- The maternal mortality rate is the number of maternal deaths per year per 100 000 females in the reproductive age group (15–49 years). This takes into account not only the obstetric risk but also the frequency with which women are exposed to that risk.

- The lifetime risk of maternal death is a measure of women’s risk of becoming pregnant as well as the risk of dying while pregnant. It is calculated by dividing the number of maternal deaths in the reproductive period by the number of women entering the reproductive period.

As is obvious from these definitions, all measures of maternal mortality require that the number of maternal deaths be counted. The best way to do this is through the vital registration system. Unfortunately, especially in countries in which maternal mortality is high, the vital registration system is incomplete. Even where the registration system is almost complete, there may be 10–40% of underreporting. In some countries, such as the UK and South Africa, committees carry out confidential enquiries into all maternal deaths, and every maternal death has to be reported to the committee by law. However, in developing countries, most births occur at home and it is possible for a woman to die of maternal causes without ever having come in contact with the health or related services, so her death remains unreported. The sisterhood method is a survey-based method whereby women are asked about any sisters who may have died in pregnancy, childbirth, or postnatal period. This method has been widely used in countries without complete vital registration to calculate the maternal mortality rate (MMR) over a set period.

Levels, Trends, Causes, And Risk Factors Of Maternal Mortality And Severe Morbidity

The WHO (2004) reported that the 2004 annual maternal mortality worldwide was 529 000, 99% of which occurred in developing countries. The lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy-related causes for a woman living in resourcepoor countries is 1 in 48, in sharp contrast to developed nations, where the risk is only 1 in 1800.

Before the start of the twentieth century, the overall maternal mortality rates worldwide were similar. By about 1900, maternal mortality in Europe and North America had started a gradual decline, mainly as a result of improvements in sanitation and living conditions, although it showed quite a lot of variation between countries even within the developed world. In 1900 the maternal mortality rates were the lowest in Sweden and northern Europe (approximately 200 deaths/100 000 live births). The MMR in England and Wales at that time was twice that of Sweden but half that of the United States, which had an MMR of about 700. In the 1930s, a sharp decline occurred in maternal mortality in most developed countries, bringing rates down to the very low level of fewer than 100 deaths/100 000 live births all over Europe and in the United States. A number of interventions have been implicated in causing this decline – not least of which were the introduction of antibiotics and ergometrine, skilled attendance at delivery, and access to emergency obstetric care. These interventions resulted practically in the elimination of maternal deaths due to sepsis and hemorrhage, such that there was a shift in the burden of cause-specific mortality.

The picture in the developing countries, however, is still very different. Very little historical data are available and even recent studies conducted in these countries rarely collect information on the causes of death in a standard format or use a standard classification system as in the ICD coding. Efforts to collect country-specific data on maternal mortality were only attempted in the 1990s, and even then these efforts were largely based on modeling.

Maternal deaths may be classified as:

- Direct, that is, maternal death occurs as a result of a complication of pregnancy, labor, or puerperium.

- Indirect, that is, death occurs as a consequence of preexisting disease or diseases that developed during pregnancy but not directly as a result of the pregnancy itself.

Direct Causes Of Maternal Death

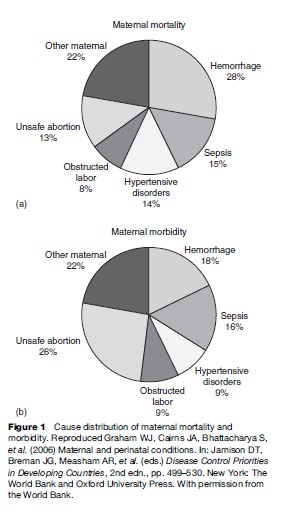

In developing countries, almost 80% of all maternal deaths occur as a result of a direct obstetric complication. Figure 1 shows maternal mortality from different obstetric causes. Where maternal mortality is high, the causes of death are similar, although the absolute levels and the proportion of death due to specific causes vary from region to region. The five main direct causes of death are relatively unvarying.

Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage or bleeding may occur antepartum, intrapartum, or postpartum and is one of the leading causes of death, especially if it occurs in the postpartum period. It is estimated that death may occur within two hours if a massive uterine bleeding, usually due to failure of the uterus to contract, is not managed immediately. The risk factors for intrapartum or postpartum hemorrhage include history of bleeding in a previous pregnancy, previous cesarean section, multiple pregnancies or polyhydramnios, placenta previa, and prolonged labor. Anemia increases the risk of dying from a hemorrhage by reducing a woman’s hematological reserve.

Genital Tract Sepsis

Puerperal sepsis is said to occur when two or more of the following conditions are present in a woman following delivery: fever, pelvic pain, abnormal or foul-smelling vaginal discharge, or delay in the reduction of the size of the uterus. Historical data indicate that in most cases puerperal sepsis is related to infection contracted during labor, and the risk of infection increases with the number of vaginal examinations. Other factors that play a role in causing intrapartum or postpartum sepsis are prolonged labor with early rupture of membranes and unhygienic birthing conditions. Sexually transmitted diseases, especially HIV infection, are associated with a higher incidence of sepsis and increased case fatality rates.

Hypertensive Disorders Of Pregnancy

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy include pre-eclampsia and eclampsia and are defined as raised blood pressure and proteinuria with or without edema; in eclampsia convulsions also occur. Although hypertensive disorders may account for fewer deaths than hemorrhage or sepsis, the absolute risk of maternal deaths from the condition is elevated in areas with high maternal mortality rates. This is because the overall incidence of hypertension is high and a high case fatality rate is associated with it. Several risk factors have been identified for hypertensive disorders, including multiple pregnancy and primiparity.

Obstructed Labor

Obstructed labor usually results from cephalo-pelvic disproportion or malpresentation. When delivery care is poor or delayed, obstructed labor frequently results in maternal or perinatal mortality or morbidity. Short stature and malnutrition in childhood predispose girls to obstructed labor later in life. A 1995 meta-analysis by WHO suggested a 60% greater likelihood of obstructed labor among women in the lowest quartile of height, compared with the highest quartile. Maternal death occurs mostly from a ruptured uterus or from massive hemorrhage and/or sepsis. Perinatal death occurs almost invariably as a consequence of obstructed labor unless cesarean section delivery is undertaken. One of the other serious maternal conditions that may occur as a result of obstructed labor is an obstetric fistula. A fistula causes fecal or urinary incontinence and can make life for a woman suffering from it seem worse than death due to social ostracism.

Unsafe Abortion

Unsafe abortion accounts for a significant proportion of maternal deaths. The risk of death varies significantly between world regions, however, from 1 death per 1900 induced abortions in Europe to 1 in 150 in Africa. Unsafe abortions lead to death through incomplete abortion, sepsis, hemorrhage, genital and abdominal trauma, perforated uterus, or poisoning from abortifacient medicines. Unwanted pregnancies, absence of legal contraception, and pregnancy termination services predispose women to unsafe abortions by unskilled attendants.

Indirect Causes Of Maternal Death

The two most important indirect causes of maternal death in the developing world are anemia and infection.

Anemia

Anemia is probably the most prevalent indirect cause of maternal mortality and severe morbidity in resourcepoor countries. Anemia occurs physiologically in pregnancy due to hemodilution, and when this is superimposed on the chronic condition caused by nutritional deficiency and infection, it can give rise to severe anemia of pregnancy, with hemoglobin of less than 7 g/dl. As a result, heart failure may occur during pregnancy or labor. Anemia also increases the risk of death from intrapartum or postpartum bleeding or sepsis. There is clear evidence to suggest that women with severe anemia run a risk of dying in pregnancy and childbirth which is 3 to 5 times greater than that of women without anemia.

Infection

The cell-mediated immune response is dampened in pregnancy and thereby makes the pregnant woman more susceptible to infections such as tuberculosis and malaria. Moreover, the severity of the infections is also increased in pregnancy and results in a corresponding increase in risk of dying from the condition. Other important infections in pregnancy include viral hepatitis and AIDS.

Sociodemographic Determinants Of Maternal Health

The sociology of pregnancy and giving birth is culture specific but influences maternal health to no less a degree than the medical conditions. Some of the sociodemographic factors are obvious, such as age at first pregnancy or contraceptive behavior, whereas others such as lifestyle and cultural factors exert a covert influence.

- Age: Extremes of age pose risks for the health of the mother, not only in physical terms, but also in terms of psychosocial well-being. This effect is more prominent in primigravid women. Although ages 15 to 49 years are generally accepted as within childbearing age, teenage pregnancy is a problem in both developed and developing societies. In recent times, assisted reproductive technology and lifestyle choices have meant that more women are postponing pregnancy either voluntarily or involuntarily to an older age. This is not without health and social implications for the mother as well as the baby.

- Birth spacing: A technical consultation meeting organized by WHO recommends a minimum interval of 24 months after a live birth and at least 6 months after a miscarriage or termination before the next pregnancy in order to minimize maternal and perinatal risks. This recommendation should, however, be assessed in light of maternal age, parity, previous obstetric history, and family aspirations.

- Substance misuse in pregnancy: Smoking while pregnant has detrimental effects on the baby. Smoking in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy can result in miscarriage or preterm delivery and accounts for up to 25% of low-birth-weight infants. Smoking has also been implicated as a cause of cot or crib death. With regard to alcohol, most of the evidence comes from the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 6.7 births per 10 000 live births result in fetal alcohol syndrome. At the less extreme end, moderate to high alcohol consumption can cause miscarriage, preterm birth, and growth restriction of the baby.

- Nutrition in pregnancy: Both under and overnutrition of the mother affect the baby adversely. Severe proteincalorie malnutrition and micronutrient deficiency can result in preterm delivery and a growth-restricted baby, whereas overnutrition and maternal obesity are associated with preeclampsia, diabetes, increased operative deliveries, and stillbirth.

Organization Of Maternal Health Care

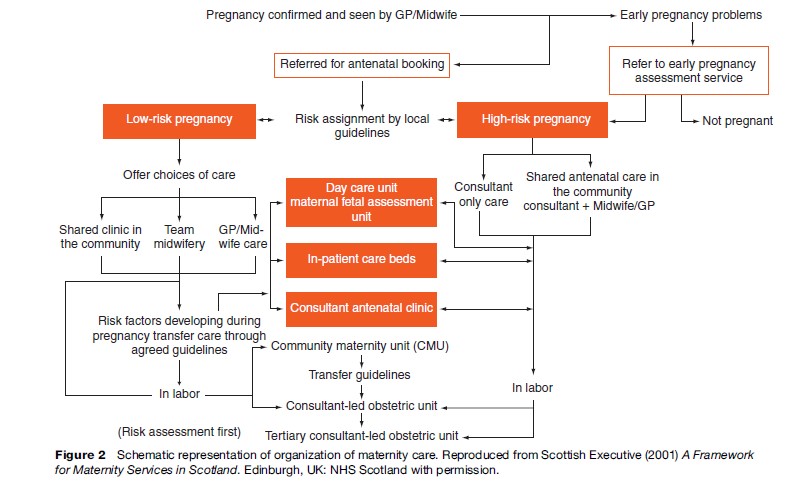

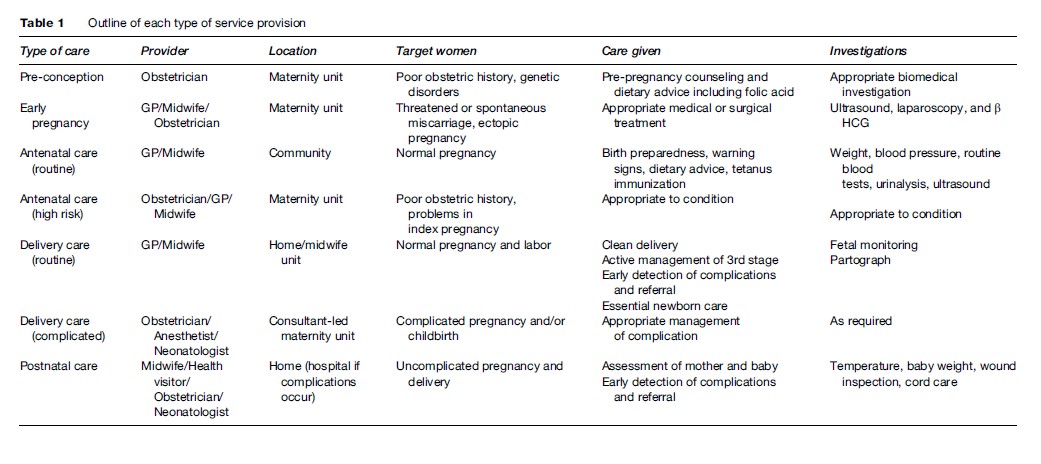

Figure 2 shows a schematic representation of how maternal health care should be organized. Structurally the care is organized into separate but interrelated groups according to the time of pregnancy (Table 1).

Prepregnancy And Early Pregnancy Services

Good health before and during early pregnancy benefits the mother, the baby, and the wider family. Every woman should have access to prepregnancy counseling and advice regarding smoking cessation, alcohol consumption, and dietary advice, including folic acid consumption to prevent neural tube defects in the baby. Moreover, women with poor obstetric history, medical problems, and family history of relevant serious illness benefit from early pregnancy services. Early pregnancy service also deals with any untoward symptoms such as bleeding and abdominal pain and arranges appropriate investigations and treatment. The provider of this service varies according to the severity of the situation. Routine prepregnancy and early pregnancy services can be delivered at the community level by a midwife or a general practitioner (GP); high-risk or symptomatic cases need to be managed at specialist centers with appropriate management facilities.

Antenatal Care

Maternity services should provide a woman a family centered, locally accessible, midwife-managed, comprehensive and effective model of care during pregnancy with clear evidence of cooperation between primary, secondary, and tertiary services. This is the basis of provision of antenatal care (ANC). Antenatal clinics were started between 1915 and 1920 in the United States, Australia, and Scotland to screen healthy pregnant women for signs of disease. In recent times, the emphasis has shifted from provision of antenatal care to provision of obstetric care at delivery in order to prevent maternal morbidity and mortality. This is because of the paradigm shift from the at-risk approach to treating every pregnancy as possible high-risk. However, ANC is still considered to be of benefit, especially to the baby, for early detection of pregnancy complications and for preparing women for delivery. A recent multicenter trial (Villar et al., 2001) conducted by WHO highlighted that routine antenatal care can be delivered by no more than four visits to the clinic. Based on a systematic review of different models, WHO recommend the following content for routine antenatal care:

- History taking of previous obstetric events, complaints in index pregnancy, and any relevant previous medical history;

- Clinical examination, height and weight, blood pressure;

- Obstetric examination for gestational age estimation, fetal heart, determination of presentation and position;

- Gynecological examination;

- Urine test (multiple dipstick);

- Laboratory investigations: hemoglobin, blood group and Rh status, syphilis and any other symptomatic sexually transmitted infection;

- Advice on emergencies, birth preparedness, delivery, and lactation;

- Education about clean delivery and recognizing warning signs;

- Iron and folic acid supplementation;

- Tetanus toxoid immunization.

Although this content forms the basic package for routine antenatal care, several other interventions are often delivered from the antenatal clinics that are relevant to the consumer population. Voluntary HIV testing and counseling, screening and treatment of syphilis, and antenatal screening for congenital abnormalities are some interventions commonly delivered during the antenatal period.

In addition to routine antenatal care, maternal health services also manage any complications occurring in the antenatal period; often at a higher referral level. This constitutes evidence-based management of antepartum hemorrhage, pregnancy-induced hypertension, preterm labor, growth-retarded baby, and any other pregnancy-related complication.

It has to be remembered, however, that antenatal care is effective in improving the health of the mother and the baby and in preventing perinatal deaths, but it has a limited role in preventing maternal mortality.

Delivery Care

As with antenatal care, delivery care is provided at two levels. At the community level, routine delivery care is given to all women having uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries; referral to a higher-care center is sought at the first sign of any complication. The challenges of delivery care in developing countries center around the safety of childbirth, whereas in countries where safety is accepted as the norm, the issues are more around choice and giving every woman the right to choose how and where they give birth.

Basic delivery care consists of the following:

- Clean birthing technique;

- Active management of the third stage of labor;

- Early cord clamping;

- Controlled cord traction;

- Oxytocics on the birth of the anterior shoulder;

- Essential newborn care.

In addition to this, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) also recommend that the following elements be available at the primary level of care:

- Parenteral antibiotics;

- Parenteral oxytocic drugs;

- Parenteral sedatives/anti-convulsants (e.g. magnesium sulphate) for pre-eclampsia/eclampsia;

- Facilities for vacuum or forceps delivery;

- Facilities for manual removal of placenta;

- Facilities for removal of retained products of conception.

These elements form what is termed ‘basic essential obstetric care.’ Over and above these, the services constitute ‘comprehensive essential obstetric care,’ usually delivered at a district hospital level, if facilities are available for:

- Cesarean section;

- Blood transfusion.

At the tertiary level, consultant-led maternity units providing a full range of services to women with high-risk pregnancies should have available:

- Obstetric/midwifery specialist services;

- Anesthetic services and access to adult intensive care;

- Neonatal resuscitation facilities and access to neonatal intensive care;

- Round-the-clock radiology and imaging;

- Round-the-clock laboratory facilities;

- Blood transfusion.

It is also recommended that maternity services have a holistic approach providing a fully integrated childbirth service tailored to the individual needs of women, preferably with continuity of care.

Postnatal Care

The postnatal period is perhaps one of the most crucial times in a woman’s life. It is the 6 to 8 week period following the end of a pregnancy. This period is important because:

- Approximately 60% of the complications occur during this period;

- Postnatal depression can occur at this time;

- It is the crucial time for establishing breastfeeding;

- It is the appropriate time to give contraceptive advice.

The purpose of postnatal services is to facilitate the transition of women and their families into parenthood. Although for most women and their babies this period will be uncomplicated, maternity services need to ensure that any complication is prevented or detected early and managed appropriately.

The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2006) in the UK has developed guidelines for the core care of women and their babies during this period based on the best available evidence:

An individualized women-centered care plan should be developed in the antenatal period and reviewed regularly during the postnatal period.

- Women should be given adequate information to promote their own health and that of their babies.

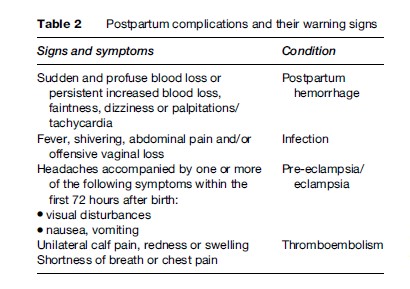

- Women should be educated about the warning signs for potentially life-threatening conditions (see Table 2) and call for help if any of them occurs.

- Breastfeeding should be actively promoted.

- Women’s emotional well-being should be assessed to detect any early signs of depression.

- Advice and information relating to the health of the baby should be offered.

In addition, if any complications given in Table 2 occur, health services should manage the condition appropriately.

Utilization Of Care

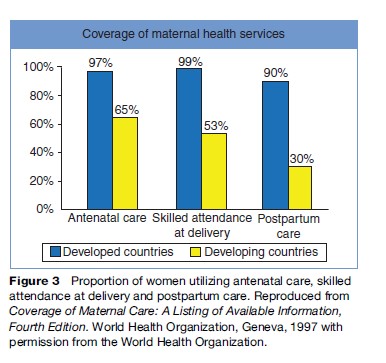

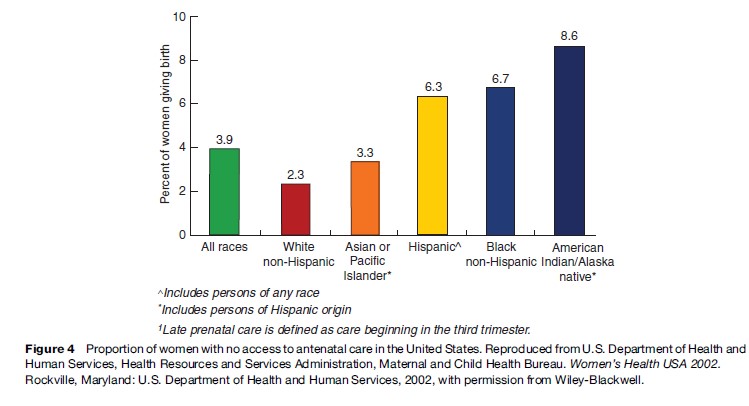

Inequalities exist in the uptake of any health care, but particularly in maternity services. Differentials exist not only when regions of the world are compared (Figure 3) but also within each country or region between the rich and the poor or among different ethnic groups (Figure 4).

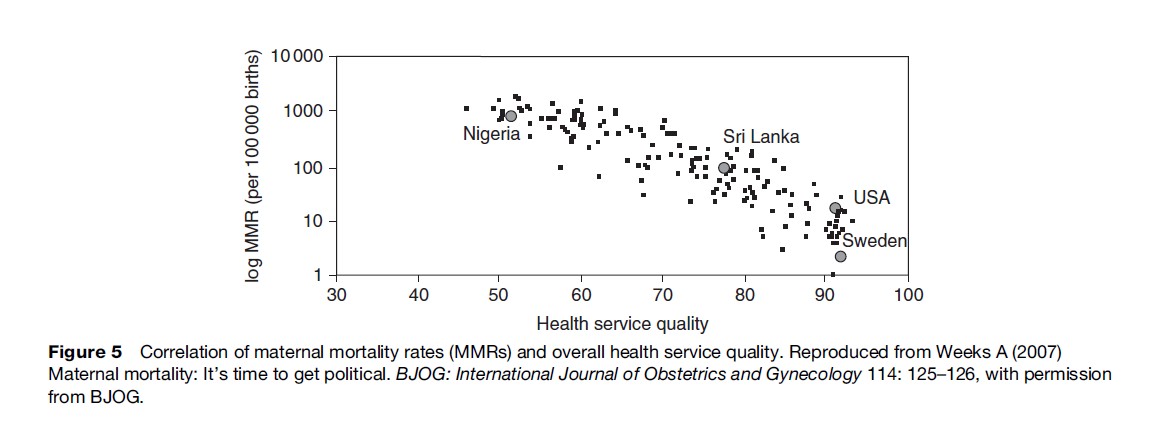

Poverty has long been implicated as a determinant of health and health-care utilization. Its relationship with maternal health is, however, rather more complex. For example, Nigeria is ranked 47th in the world in terms of its gross domestic product (GDP) but has a maternal mortality ratio of 800 per 100 000 live births. This is in sharp contrast to Sri Lanka, which is ranked 78th but has a maternal mortality ratio of 92 per 100 000 live births. On the other hand, Graham et al. (2004), exploring the relationship between maternal mortality and poverty quintiles developed by the World Bank, found a close correlation in seven different countries. It has been postulated that with maternal health care, gender-related factors and women’s empowerment play an important role. Another factor that correlates well with maternal mortality is the quality of maternal health services, as Figure 5 shows.

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Save the Mothers initiative in Uganda and the UNFPA project in India found that improving the quality of maternity care also improved uptake of the care.

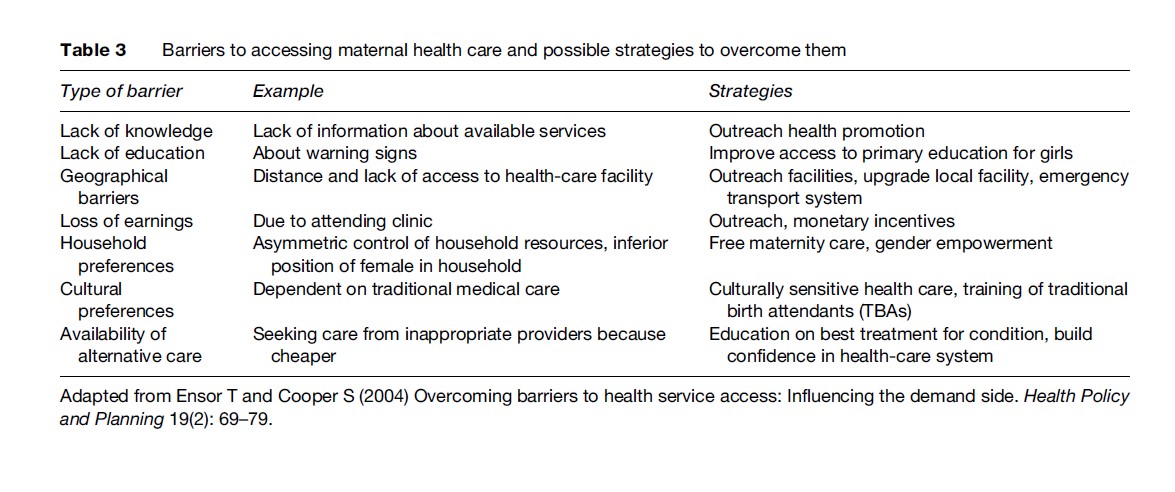

Table 3 highlights some of the barriers encountered in accessing maternal health care and some examples of interventions to overcome them.

The Cost And Financing Of Maternal Health Services

There is much in the way of published literature regarding the cost of maternity care, but inconsistencies in costing methods and definitions of maternal health make cross country comparisons difficult. Indeed, global methods for modeling cost-effectiveness (Mother Baby Package; WHO-CHOICE; Disease Control Priority Project – DCPP) have limited value at country level, where priority setting and policy decisions are made. Nevertheless, they offer a standardization of costing methods. Overall, the findings from several studies suggest that maternal health care is cheaper if delivered at the primary care level and therefore upgrading a primary health center to deliver basic emergency obstetric care is a cost-effective option. Although obstetric surgery and blood transfusion can only be offered at the level of secondary care, a great many of the life-saving interventions can be carried out at primary level (Maine, 1999). Implicit in this tiered approach is the presence of an effective referral and transport system.

The estimated costs of the components of a maternal health-care system are as follows (Borghi, 2001):

Antenatal care: US$2.21 (Uganda) to US$42.41 (Argentina) per visit

Normal vaginal delivery: US$2.71 (Uganda) to US$140.41 (Argentina)

Routine postnatal care: approximately same as antenatal care

From a review of the published literature, some other generalizable findings emerge: (1) Personnel, drugs, and medical supplies are the main contributors to total cost, and directing resources toward these recurrent costs benefits women in the long run; (2) the cost of a cesarean section is three times that of a vaginal delivery; therefore use of cesarean section, when not clinically indicated, is neither cost effective nor beneficial to the mother or baby.

Borghi (2001) reports that in developing countries, 4–12% of domestic health expenditure is devoted to maternal health care. Apart from the National Health Service in the UK, where the entire maternity care is financed by internal revenue and government subsidies, all other countries need to find alternative sources of funding. These may be:

- Direct government financing;

- Donor financing;

- Private user charges;

- Third-party payments (e.g., health insurance, community financing or mutuelle schemes).

Most health systems are financed by a mixture of these sources.

Quality Assurance

Although we now know that quality assurance of health services is imperative and should ideally be built in with the services, the measures of quality and standards are variable and culture specific. Although in sub-Saharan Africa, quality assurance of maternity services means having a regular supply of drugs and well-trained health care providers, in the developed countries, this means not only providing clinically effective care but also giving women the choice of how, where, and when to give birth. As Weeks (2007) points out, in order to improve MMR and meet the Millennium Development Goals, governments need to promote high-quality maternity services, especially in rural areas. This implies a decentralization of health-care systems, regularity of staff training and consumables supply, and national and local audits to periodically evaluate the service. These audits may be either critical incident audits, such as the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths, or criterion-based clinical audits with appropriate clinical standards. In addition, dialogue with consumers and key stakeholders is equally important in order to assess their requirements.

Issues And Challenges

HIV/AIDs

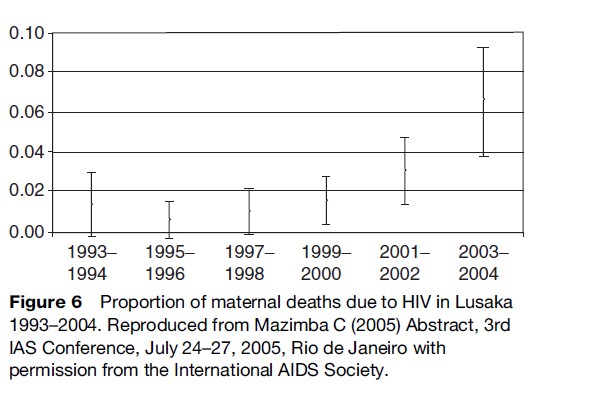

One disease that has changed the epidemiology of chronic diseases and put a major burden on health services is HIV infection. Because this is a sexually transmitted disease and is likely to affect men and women of the reproductive age group, its impact on maternal health cannot be overestimated. In some countries, such as South Africa, it has become the principal cause of maternal mortality. Moreover, because of the stigma attached to it, maternal deaths from AIDS tend not to be reported, thus posing a major problem in measuring the outcome. The challenges of diagnosing and treating HIV/AIDs are beyond the scope of this research paper, but any article on maternal mortality or maternity services would be incomplete without touching upon the effect of HIV on maternal health, as is illustrated by Figure 6.

Overmedicalization Of Birth

Because many pregnancies will pass uneventfully and end happily with a healthy mother and a healthy baby, the concept of ‘first do no harm’ is particularly applicable to maternity care. There are many examples of maternal morbidity and even mortality that can occur as a result of overenthusiastic but misinformed medical care: The inappropriate use of oxytocics, the overzealous curettage of the postabortion uterus, and cesarean section without clinical indication, to name but a few. As an added complexity, there is the issue of malpractice suits, especially when health care is self-financed, which has given rise to overmedicalization of the natural process of birth. Issues of choice regarding the place and time of delivery, ‘designer babies’ (an often pejorative popular scientific and bioethics term that specifies a child whose hereditary makeup, or genotype, would be selected via various reproductive and genetic technologies) and cesarean section on maternal request have all been in the news recently in developed countries but are issues probably far removed from the reality for the mother struggling across the mountains of Afghanistan to reach a healthcare facility.

Pain Relief In Labor

As motherhood became as safe as was possible to make it in the developed world, the issue of making childbirth a satisfying experience for the mother became the next target. Since labor pain is often referred to as the worst aspect of childbirth, the provision of obstetric analgesic services has now become the norm in most large hospitals in the developed countries. This service is able to offer laboring women a choice of pain relief in terms of premixed nitrous oxide and oxygen gas, parenteral opioids, and epidural analgesia with minimal effects on the baby.

Implications For Health Policy

It has long been acknowledged that the health of mothers is of paramount importance not just to the family but also to the health of the nation. Despite this, maternal mortality continues to be a major health concern, especially in the developing world. Yet less than a century ago, maternal mortality in countries such as the United States and UK was as high, if not higher, than some of the developing countries today (Loudon, 1997). Several factors, such as new drugs and technologies and improved living standards, played a part in bringing about this transformation, but the greatest difference was made by the political will to effect changes in the health system and society. In the UK, the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths was set up in 1928 by the Ministry of Health and functions to this day as an example of quality assurance in women’s health care.

Efforts were made to translate the experiences of the UK, United States, and Sweden into a global effort. In 1930, the League of Nations’ health section noted the high maternal mortality in some countries and expressed a will to transfer some of the medical progress made in developed countries to their colonies.

In 1978, the International Conference on Primary Health Care was held in Alma Ata, where it became obvious that simply transferring medical care models from developed to developing countries would not work. Around this time the emphasis shifted to family planning methods, and national policies relating to curbing the population inflation were supported by global organizations such as the UN.

By 1987, improvements in data collection informed an awareness of the extent of the problem of maternal mortality, and the concept of Safe Motherhood as an international political agenda was born. The first international Safe Motherhood conference was held in Nairobi in 1987. Two years later, the World Summit for Children took place in New York. Although this summit emphasized the importance of monitoring and reducing maternal mortality, it was only in the context of child survival.

In the mid-1990s, three international meetings – the International Conference on Population and Development (Cairo, 1994), the Fourth World Conference for Women (Beijing, 1995), and the Social Summit (Copenhagen, 1995) – all viewed Safe Motherhood in the larger context of reproductive health. The growing interest in maternal health toward the end of the twentieth century culminated in an interagency technical consultation in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in October 1997. This consultation brought together Safe Motherhood specialists and policy makers from all over the world to decide on a way forward for the Safe Motherhood movement. Since then, there have been several meetings held and many nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have come forward with a commitment to Safe Motherhood, not the least of which are the WHO, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), and UNFPA (AbouZahr, 2003):

In the words of Professor Fathalla, expresident of FIGO:

Maternal deaths in developing countries are often the ultimate tragic outcome of the cumulative denial of women’s human rights. Women are not dying because of untreatable diseases. They are dying because societies have yet to make the decision that their lives are worth saving.

Maternity is a social function and not a disease. When women are risking death to give life, they are entitled to have their own right to life and health protected. Societal attitudes of looking at women as means and not ends have resulted in the denial of women’s rights to essential maternity services. A signal of hope is that safe motherhood is now on the world agenda as one of eight Millennium Development Goals. The global community of obstetricians has a major responsibility to help make motherhood safer for all women. (Fathalla, 2006)

Bibliography:

- AbouZahr C (2003) Safe motherhood: A brief history of the global movement 1947–2002. British Medical Bulletin 67: 13–25.

- Borghi J (2001) What is the cost of maternal health care and how can it be financed? De Brouwere V and Van Lerberghe W (eds.) Safe Motherhood Strategies: A Review of the Evidence, Health Services Organisation and Policy, vol. 17, pp. 245–292. Antwerp, Belgium: ITG Press.

- Ensor T and Cooper S (2004) Overcoming barriers to health service access: Influencing the demand side. Health Policy and Planning 19(2): 69–79.

- Fathalla MF (2006) Human rights aspects of safe motherhood. Best Practice & Research in Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 20(3): 409–419.

- Graham WJ, Fitzmaurice AE, Bell JS, and Cairns JA (2004) The familial technique for linking maternal death and poverty. Lancet 363(9402): 23–27.

- Loudon I (1997) Midwives and the quality of maternal care. In: Marland H and Rafferty AM (eds.) Midwives, Society and Childbirth: Debates and Controversies in the Modern Period, pp. 180–200. London and New York: Routledge.

- Maine D (1999) The safe motherhood initiative: why has it stalled? American Journal of Public Health 89(4): 480–482.

- National Institute for Health Clinical Excellence (2006) Postnatal Care: Routine Postnatal Care of Women and Their Babies. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG037. (Updated July 2006; accessed December 2007.)

- Scottish Executive (2001) A framework for maternity services in Scotland. Edinburgh, UK: NHS Scotland.

- Villar J, Ba’aqueel H, Piaggio G, et al. (2001) WHO antenatal care randomized trial for the evaluation of a new model of routine antenatal care. Lancet 357: 1551–1564.

- Weeks A (2007) Maternal mortality: It’s time to get political. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. International Journal of Obstectrics and Gynecology 114: 125–126.

- WHO (1992) International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th rev. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- WHO (2004) Maternal Mortality in 2000: Estimates Developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Reproductive Health and Research.

- Adam T, Lim SS, Mehta S, et al. (2005) Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for maternal and neonatal health in developing countries. British Medical Journal 331: 1107.

- Duong DV, Lee AH, and Binns CW (2005) Measuring preferences for delivery services in rural Vietnam. Birth 32(3): 194–202.

- Graham WJ, Cairns JA, Bhattacharya S, et al. (2006) Maternal and perinatal conditions. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG Measham AR, et al. (eds.) Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries, 2nd edn., pp. 499–530. New York: The World Bank and Oxford University Press.

- Hotchkiss DR, Krasovec K, El-Idrissi MD, Eckert E, and Karim AM (2005) The role of user charges and structural attributes of quality on the use of maternal health services in Morocco. International Journal of Health Planning Management 20(2): 113–135.

- Hundley V, Rennie A, Fitzmaurice A, Graham W, van Teijlingen E, and Penney GA (2000) National survey of women’s views of their maternity care in Scotland. Midwifery 16(4): 303–313; erratum 2001, Midwifery 17(2): 161.

- Ikeako LC, Onah HE, and Iloabachie GC (2006) Influence of formal maternal education on the use of maternity services in Enugu, Nigeria. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 26(1): 30–34.

- Jamison DT, Shahid-Salles SA, Jamison J, Lawn JE, and Zupan J (2006) Incorporating deaths near the time of birth into estimates of the global burden of disease. In: Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. (eds.) Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. New York, USA: The World Bank and Oxford University Press.

- MacKeith N, Chinganya OJ, Ahmed Y, and Murray SF (2003) Zambian women’s experiences of urban maternity care: Results from a community survey in Lusaka. African Journal of Reproductive Health 7(1): 92–102.

- McCaw-Binns A (2005) Safe motherhood in Jamaica: From slavery to self-determination. Paediatrics and Perinatal Epidemiology 19(4): 254–261; discussion, 261–262.

- McKay S (1993) Models of midwifery care: Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands. Journal of Nurse Midwifery 38(2): 114–120.

- Peterson WE and Mannion C (2005) Multidisciplinary collaborative primary maternity care project. A national initiative to address the availability and quality of maternity services. Canadian Nurse 101(9): 25–28.

- Poliner RAG (1994) An Analysis of the Costs and Effects of Three Levels of Maternity Services in West Philadelphia. Thesis, University of Pennsylvania. http://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/ AA19427599.

- Rozette C, Houghton Clemmey R, and Sullivan K (2000) A profile of teenage pregnancy: Young women’s perceptions of the maternity services. Practising Midwife 3(10): 23–25.

- Short S and Zhang F (2004) Use of maternal health services in rural China. Population Studies (Camb) 58(1): 3–19.

- Tucker J, Hundley V, Kiger A, et al. (2005) Sustainable maternity services in remote and rural Scotland? A qualitative survey of staff views on required skills, competencies and training. Quality and Safety in Health Care 14(1): 34–40.

- Turnbull DA, Wilkinson C, Gerard K, et al. (2004) Clinical, psychosocial, and economic effects of antenatal day care for three medical complications of pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial of 395 women (see Comment). Lancet 363(9415): 1104–1109.

- Young D, Shields N, Holmes A, Turnbull D, and Twaddle S (1997) Aspects of antenatal care. A new style of midwife-managed antenatal care: Costs and satisfaction. British Journal of Midwifery 5(9): 540–545.

- Zelmer J and Leeb K (2004) Challenges for providing maternity services: The impact of changing birthing practices. Health Quarterly 7(3): 21–23.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.