This sample Occupational Injuries and Workplace Violence Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Definition And Scope

Occupational injuries are defined by Hagberg et al. (1997) as any damage to the body by energy transfer during work with a short duration between exposure and the health event (usually less than 48 h). Occupational injuries are distinct from occupational diseases in that they are caused by acute exposure in the workplace to physical agents such as mechanical energy, electricity, chemicals, and ionizing radiation, or from the sudden lack of essential agents such as oxygen or heat. Examples of events that can lead to worker injury include motor vehicle crashes, assaults, falls, being caught in parts of machinery, being struck by tools or objects, and submersion. Resultant injuries include fractures, lacerations, abrasions, burns, amputations, poisonings, and damage to internal organs.

The definition of work relatedness varies among agencies, data sources, and countries. In addition to the common definition of ‘working for compensation,’ other situations such as working in the informal economy, children working for a family business or farm, volunteering, performing domestic duties, and commuting to and from work are inconsistently included in definitions of working. Variations in how occupational injuries are defined and recorded make global estimates and international comparisons difficult and inexact.

Yet there is no question that occupational injuries are a serious public health problem. Concha-Barrientos et al. (2005) estimate that over 300 000 workers worldwide die each year from occupational injuries. Globally, approximately 3.5 years of healthy life are lost per 100 000 workers each year due to injuries at work. Occupational risk factors account for an approximate 9% of the global burden of mortality from unintentional injuries (excluding injuries from violence).

Occupational Versus Nonoccupational Injuries

Many injury causes that are common in the workplace are also common in other environments. Transportation events, violence, falls, and being struck by objects are examples of injury causes that are common in multiple settings. Others are more common to the workplace, such as machinery, electrocutions, and explosions. Strategies for reducing and preventing injuries in multiple settings include changes to the environment (such as changes in roadway design), regulatory policy (such as specifying product safety parameters), and educational approaches. While broad injury prevention measures, such as those focused on improving roadway safety, reduce the risk of injury and death to the general public, these countermeasures may also help improve workplace safety.

Research on occupational injuries has relevance in other settings for several reasons: Common methods, risks, and prevention strategies; overlap between work and non-work tasks and environments; and the advantage of work settings as natural laboratories for testing and evaluating injury prevention strategies.

Studies that elucidate risk factors and develop and evaluate effective intervention strategies in one setting can often be applied in others. For example, motor vehicles are the leading cause of injury-related death worldwide, and the leading cause of work-related injury deaths in most, if not all countries. Interventions that were developed to prevent injuries to the general public, such as seat belts and air bags, also prevent injuries and deaths among those for whom the vehicle is the workplace. In fact, they may be even more effective in this context because their use may be more enforceable by employers. Conversely, prevention efforts developed specifically for truck drivers and other transportation workers, such as back-up sensors and collision warning systems, also provide protection to the motoring public.

In some environments, the risks of occupational and nonoccupational injuries are difficult to distinguish, such as on farms where families both live and work in a hazardous environment; in schools where students and teachers alike are exposed to the growing risk of intentional injuries; and in health-care settings where there are similar risks for workers and patients. As a relatively controlled environment, the workplace can provide an ideal setting, a living laboratory for intervention evaluation studies. Similarly, workplaces offer an opportunity for widespread implementation of prevention technologies and strategies, and for studying and improving dissemination and technology transfer strategies.

Finally, injuries in all settings and among all populations are complex events with multiple contributors that require the application, knowledge, skills, and efforts of many disciplines to understand and prevent them. These multifactoral events require collaborative expertise in multiple disciplines to effectively identify risk factors and develop and implement prevention strategies. The disciplines of epidemiology, social and behavioral sciences, occupational medicine and nursing, safety sciences, ergonomics, industrial hygiene, criminology, law enforcement, architecture, and engineering all offer important expertise to occupational injury prevention.

The Public Health Approach To Prevention

Over 50 years ago, the public health community began to view injury as a public health problem, which could be addressed much in the same way infectious diseases had been for several centuries. The public health approach to prevention is based primarily upon the science of epidemiology: The study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events in specified populations and the application of this study to control health problems. The public health approach to injury research and prevention includes the following steps:

- Identify and prioritize problems through injury surveillance;

- Quantify and prioritize risk factors through analytic injury research;

- Identify existing or develop new strategies to prevent or control occupational injuries;

- Implement the most effective injury control measures through communication/dissemination/technology transfer, and then

- Evaluate and monitor the results of intervention efforts.

The public health approach begins with the collection of data. Through surveillance, injuries are identified and patterns of existing or emerging injury problems can be tracked. Surveillance data enable the establishment of prevention priorities, identification of areas where further research is needed, monitoring of injury trends, and the tracking of progress of injury prevention efforts.

After injury problems have been identified, analytic research may be used to identify causal mechanisms and risk factors that produce or contribute to injuries. The next step is to identify existing or new strategies to mitigate risk factors to prevent injuries. In some cases, prevention measures are available but are not widely used. In other cases, prevention measures do not exist or are inadequate. Options may vary in effectiveness, cost, and feasibility. This component of the public health model may require the most multidisciplinary collaboration – between engineers, epidemiologists, social scientists, and others. Prevention measures can range from organizational and administrative controls, including procedures and training, to engineering controls and regulations. Assessing the feasibility, effectiveness, and cost effectiveness of promising prevention measures is a critical step in the process of identifying prevention options. Prevention strategies must then be communicated and transferred to those who can implement them in the workplace. Once implemented, prevention measures and programs should be evaluated to determine whether they are having the intended effect.

The public health approach to occupational injury prevention entails a multidisciplinary research approach on a continuum from data-driven problem identification to workplace implementation of prevention strategies. For some problems, the magnitude or risk is unknown and surveillance is the necessary first step. For others, the causes are known and intervention development or evaluation of existing interventions is needed. In other areas, effective interventions are known and efforts to transfer and implement are needed. The public health framework allows research activities to be structured sequentially from data-driven priorities to facilitating transfer and adoption of research findings into the workplace.

Data Sources

There are a variety of occupational injury data sources. Some governments have agencies that document occupational injuries based on reports from employers, employer surveys, or insurance programs created specifically to compensate workers with occupationally related injuries and illnesses. There is considerable variability among these available governmental data sources in terms of the types of workers encompassed, work-relatedness definitions, and severity of injuries that are included. In some governmental sources, only selected economic activities are included, leaving out major high-risk sectors such as agriculture or groups such as the self-employed. Some sources require that a worker be absent from work for a minimum period of time before the injury is recorded or reported. Motor vehicle injuries to workers who drive as part of their job, injuries while commuting, and workplace violence are differentially covered. The informal work sector is excluded from most governmental data sources and underreporting is common among specific groups and overall. It is important that users of occupational injury data understand the limitations of the surveillance system and the types of workers and injuries that are encompassed in, or excluded from, the data. It is generally recognized that governmental data sources underrepresent the true incidence of occupational injuries. The International Labour Organization compiles occupational injury statistics from numerous governments and provides information on methods used in each country. The variation in coverage is important to recognize and consider.

Additional data are available from government and research agencies that are not focused on occupational injuries, but include occupational injuries. When these data sources include a means to specifically identify injuries associated with work (for example, answers to questions such as ‘injury at work?’ or indication of payment for health care by workers’ compensation systems), these data can be used to study and report on the incidence and patterns of occupational injuries. These nonoccupational data sources are important for assessing the burden of injuries in the workplace compared to other settings, describing occupational injuries that may not be captured by official government statistics, and providing detailed data that might not otherwise be available in occupational injury data sources. Examples of nonoccupational data sources that may include data on occupational injuries are death certificates and registries, data from hospitals and other health-care settings, health surveys of the general population, data on transportation-related events, and data on violence and crime collected by law enforcement agencies.

Employers, trade and labor unions, and research organizations are other sources of data on occupational injuries. Some employers keep detailed records on occupational injuries that can be useful for monitoring occupational injuries in specific work settings and guiding work-placespecific injury prevention efforts. Trade and labor unions and research organizations use a variety of methods to estimate, characterize, and track occupational injuries, including survey methodology.

Causes And Risk Factors

Although the immediate cause of injury is exposure to energy or deprivation from essential agents, injury events arise from a complex interaction of factors associated with the vector or vehicle that is the immediate source of injury, the injured person or host, and the social and physical environment. In occupational settings, these factors include physical hazards in the workplace or setting, hazards and safety features of machinery and tools, the development and implementation of safe work practices, the organization of work, the design of workplaces, the safety culture of the employer, availability and use of personal protective equipment (PPE), demographic characteristics of workers, experience and knowledge of workers, and economic and social factors.

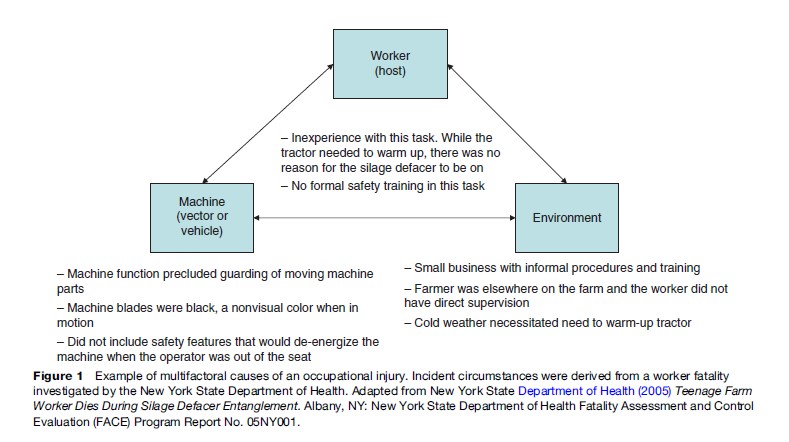

Figure 1 illustrates how occupational injury events can be caused by multiple contributory factors.

Prevention Strategies

Over the years, a number of models for occupational injury prevention have evolved. Two prominent and complementary approaches are the Haddon Matrix that uses a systematic approach to identify points of intervention, and a hierarchy of controls, with an emphasis on controls that minimize the role of human behavior.

Haddon Matrix

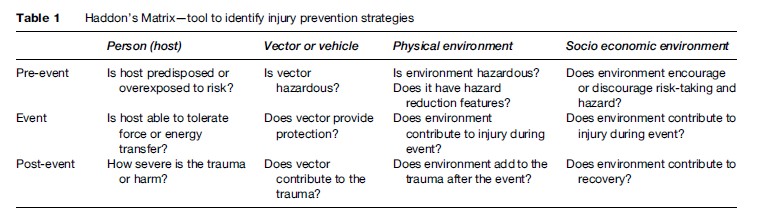

Haddon (1968) introduced the concept that injury causation was a chain of multifactoral events, each of which provides opportunities for intervention. Haddon developed a widely used matrix in the injury prevention field that facilitates an examination of different points of intervention related to the human or host, vector or vehicle, and the physical and social environment across the time sequence of an injury event: Pre-event, event, and post-event. The Haddon Matrix is depicted in Table 1. Haddon also proposed ten basic strategies for injury prevention that have a number of similarities to the hierarchy of controls approach.

Hierarchy Of Controls

The hierarchy of controls model is a prioritized set of prevention strategies, presented here in order of priority as adapted from Barnett and Brickman (1986):

- Eliminating hazards through design;

- Using safeguards that eliminate or minimize worker exposure to hazards;

- Providing warning signs or devices to identify hazards;

- Training workers in safe work practices and procedures;

- Using personal protective equipment (PPE) to prevent or minimize worker exposure to hazards or to reduce the severity of an injury if one occurs.

Three main categories of control strategies correlate with the hierarchy of controls approach: Engineering controls, administrative controls, and the use of PPE. Following the hierarchy of controls approach, they can be viewed as providing prioritized tiers of protection. Engineering controls should be viewed as the primary tier of prevention.

Because it is not always possible to develop engineering controls for all occupational injury hazards, administrative controls are necessary and should be viewed as the secondary tier of prevention. PPE should be viewed as the third tier of prevention as PPE does not remove the injury hazards, but provides a means to prevent or mitigate the injury.

Engineering Controls

Engineering controls, also known as passive controls, involve eliminating hazards through design or applying safeguards to prevent worker exposure to hazards. Effective hazard elimination and safeguarding are designed or retrofitted into equipment, work stations, and work systems to provide protection without direct worker involvement: Thus the term passive controls. An example of an engineering control for the injury scenario in Figure 1 would be incorporating automatic shut-off designs into the equipment so that when the tractor operator left his seat, the silo defacer would de-energize. This would eliminate the possibility for the machine operator to be in close proximity to the machine’s moving teeth. There would still be potential hazards for other workers who might come into proximity of the energized machine during operation and administrative controls would also be needed to address these worker hazards.

Administrative Controls

Administrative controls are management-directed work practices or procedures which, when implemented consistently, will reduce the exposure to hazards and the risk of injury. They are sometimes referred to as active controls because they require worker involvement to be effective. Employer procedures for safely operating specific types of equipment or performing specific tasks are administrative controls. It is generally recognized that employer safety procedures are most effective when formal and written and when workers receive feedback on their performance of the procedures. The use of warning signs and devices is another form of administrative control.

Administrative controls require worker involvement to be effective and must be accompanied by efforts such as training, to ensure that supervisors and workers are aware of the controls and their responsibility to follow them. In the injury scenario in Figure 1, the farmer reportedly stressed to workers that the silo defacer was not to be turned on until it was in position to be used in front of the compacted silage. This would be an administrative control to minimize hazards to both the operator and other workers. The absence of formal documented safety procedures for the machine, limitations in the training, and lapses in supervision may have contributed to the ineffectiveness of administrative controls in this case. The silo defacer had prominent signs instructing workers to stand clear of the machine, but these signs in and of themselves failed in preventing the entanglement.

Training

Training refers to methods to assist workers in acquiring knowledge (safety information on potential workplace hazards), changing attitudes (perceptions and beliefs regarding safety), and practicing safe work behaviors (procedures specified by employers and equipment manufacturers). Training programs should be based on an assessment of training needs specific for the tasks the worker will be performing. Unique characteristics of the specific workforce must be considered when developing or implementing safety training programs, for example, language, literacy, cognition, and cultural issues. The effectiveness of the training should be assessed and feedback provided to workers on their knowledge and skills.

Workplace safety training appears to be most effective when it includes active learning experiences that stress worksite application, and when it is developed and implemented in the context of a broader workplace-based injury prevention approach.

Personal Protective Equipment

PPE consists of devices worn by workers to protect them, by reducing the risk that exposure to a hazard will injure the worker, or the severity of an injury if one does occur. Although the hazard still exists, the potential for worker injury is mitigated by use of PPE. The use of PPE in many work environments and situations is essential for worker protection. However, PPE is usually viewed as the lowest tier in the hierarchy of controls. If hazardous exposures cannot be eliminated through engineering controls or the application of administrative controls, then PPE provides another opportunity for worker protection. Figure 2 depicts a worker using forms of PPE, including a hard hat to protect against falling objects. Other examples of PPE include steel-toed safety shoes to protect against surface hazards and falling objects, fall-restraint devices to protect workers from injury during a fall, and respirators to protect workers from hazardous and/or oxygendeficient atmospheres.

Combined Application Of Controls

A comprehensive approach to worker injury prevention efforts inevitably includes all tiers of the control hierarchy to achieve maximum worker protection. In most work environments, a combination of engineering controls, administrative controls, and PPE will be required to have a complete and effective injury prevention program.

Roles And Responsibilities

Occupational injury prevention is not the sole responsibility of a single person or group. Employers, workers, government agencies, standards setting bodies, and researchers each share in the responsibility for prevention.

Employers

Employers are responsible for developing a comprehensive safety program and effectively implementing that program at the workplace. An effective safety program will strive to identify hazards through job safety analysis or other methods of systems safety analysis, and eliminate or control identified hazards through the various approaches previously described. An effective safety program will include management commitment; written policies and procedures that are monitored and enforced; consultation with workers and their representatives; worker training; and proper maintenance of vehicles, equipment, and machinery. As part of a comprehensive safety program, employers should require systematic reporting and tracking of occupational injuries and assessment of this information for corrective action to prevent similar occurrences. Trade associations (i.e., organizations that provide support to and advocate for groups of like businesses) can provide occupational safety guidance and resources to their employer members.

Workers

Workers play a vital role in workplace safety. Workers share the responsibility for complying with safe work practices and policies, maintaining a safe work area, and using appropriate PPE. Workers should also participate in company-sponsored training. They should report unsafe conditions for corrective action. As the experts in their jobs, workers should be involved in systems safety analysis and development of safe solutions. In many countries there are requirements for workers and their representatives, either through safety committee or trade and labor unions, to be represented in decision making around workplace health and safety issues. Trade and labor unions have played key roles in identifying the need for and advocating worker safety protections.

Government Agencies

Many developed nations have governmental agencies with mandated responsibilities for occupational safety and health. These responsibilities typically include development and enforcement of standards and regulations that specify conditions for safe work. Government regulation of worker safety can be contentious; governments frequently try to strike a balance of providing necessary worker safety protections without unnecessarily burdening employers. Some governments have agencies with responsibilities that include collecting and reporting occupational injury data and conducting occupational injury research. These governmental agencies help ensure that work conditions are monitored and that workers are provided with safe workplaces. The United Nations (UN) has two specialized agencies that address occupational safety across countries, the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). The ILO was established in 1919 and became part of the UN in 1946. The ILO formulates international labor standards, including standards that address worker safety. The World Health Organization, established in 1948, promotes health and well-being, including research and programs addressing worker safety.

Standards Setting Bodies

In addition to government agencies mandating standards for worker safety, there are numerous other standards setting bodies whose work impacts worker safety. These standards setting bodies promulgate standards that cover a multitude of hazards and address the work environment, work practices, equipment, PPE, and worker training. For example, there are numerous specifications, codes, and guidelines that address safety concerns for machinery, equipment, tools, and other materials. These standards are frequently developed using a consensus approach that involves various stakeholders and opportunities for public input. It is important to note, however, that issues related to setting standards or procedures to promote safety are often contested, as they invariably relate to the use of scarce resources, whether this be time, energy, or inputs of other forms to promote enhanced safety in the workplace. While not regulated or enforced, voluntary standards can be effective prevention strategies as market competition and labor or societal pressures often result in widespread adoption and compliance. The International Standards Organization (ISO) is a network of nongovernmental standards bodies, with participation of standards setting bodies from 157 countries in 2007.

Researchers

Researchers make contributions to workplace safety through all steps of the public health approach. Researchers help identify the incidence, patterns, and trends in occupational injuries, including important research to identify injuries not captured in official government statistics. Research is the key agent for identifying and quantifying risk factors for occupational injury across workplaces, including rigorously demanding research to assess the role of work organization and culture. Researchers develop occupational injury prevention strategies and tools, including engineering controls, and evaluate their effectiveness.

Research To Practice

Many different entities have the ability to, and responsibility for, transferring workplace injury prevention research to practice in the workplace. It has only been recently that the scientific occupational injury prevention community has recognized that the researcher must also take responsibility for ensuring that the results of their research are transferred to or toward workplace application. Every research effort, from surveillance and basic laboratory research to field and evaluation studies, must have at least one appropriate recipient of the study results who will carry out the next step in moving the new knowledge or technology toward workplace implementation. It is imperative that researchers identify and involve the appropriate recipients from the conceptual phase of the study, both to ensure the relevance and applicability of the research, as well as to ensure the results will ultimately lead to workplace implementation and worker injury prevention. There are various types of transfer recipients, as well as methods for researchers to facilitate the transfer of research results to practice. Examples include translators of scientific information to worker friendly guidance or training materials; manufacturers to develop and market safety technologies; regulators and employers to promulgate new safety policy; consensus standards bodies to develop or modify guidelines and voluntary standards; trade and labor organizations, including trade and labor unions, to advocate for and promote new health and safety practices; and companies to implement new technologies, processes, and practices to prevent injuries among their workforce.

Workplace Violence

Definitions And Classification Of Typologies

The definition of workplace violence (WPV) varies among agencies and programs (e.g., law enforcement, public health, surveillance, and compensation and benefit programs). All definitions include physical assault including bodily injury inflicted by one person on another. Definitions may include simple assaults (a law enforcement definition) due to threat with a weapon. Some define WPV to include verbal assaults or incivility, i.e., language or actions that make someone uncomfortable in the workplace.

Definitions of verbal assault may include bullying or continued threats and harassment over a long period of time. The U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (1996) recommends a working definition as ‘‘violent acts, including physical assaults and threats of assaults, directed toward persons at work or on duty.’’

In addition to differing definition of workplace violence among agencies, the definition of jobs or work relatedness associated with workplace violence also differs among agencies (Peek-Asa et al., 2001). Differing definitions make it difficult to compare estimates of workplace violence among different surveillance and research study databases.

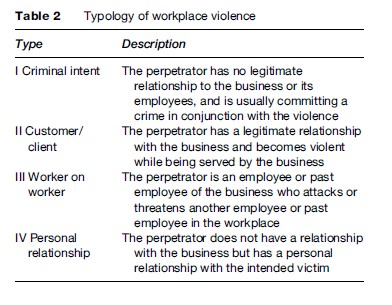

Table 2 presents a four-tiered typology for the circumstances of WPV (Peek-Asa et al., 2001). This typology is frequently used to characterize WPV events and is particularly useful for examination of WPV risk factors, and for development and evaluation of targeted WPV preventions in different industries. Type 1 is violence associated with criminal intent that is usually associated with a perpetrator committing a crime in the business establishment such as robbery, shoplifting, or loitering. Type II is violence to workers by customers, clients, patients, students, inmates, and any persons for which businesses provide services. A large proportion of type II incidents occur in the health-care industry such as in nursing homes and psychiatric facilities, where the victims are often caregivers. Other occupations that are frequently victims of type II violence are police officers, correctional staff, social service workers, and teachers. Type III violence is worker-on-worker violence, including employer-on-worker and worker-on-employer violence. In countries where employer-on-worker violence is a significant problem, a distinction in surveillance programs should be made between employer and co-worker violence. Type IV violence is violence due to personal relationships such as victims of domestic violence assaulted or threatened while at work.

Extent Of Problem – Why Workplace Violence Is A Public Health Issue

WPV is a significant public health issue due to the large number of workplace physical assaults, homicides, and lost work time. Millions of workers are injured each year during workplace assaults. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that in the United States in 2002 there were 18 104 lost work days due to work-related assaults and violent acts by persons. This is likely to be a substantial underestimate and in most settings, especially in less well-resourced countries, few if any data are reported and/or recorded. Workplace violence has been associated with stress and consequences leading to fatigue, absenteeism, and job turnover. Work-related homicide rates are highest among public safety and corrections, the retail industry, and taxicab drivers. Work-related nonfatal WPV injury rates are highest among health-care workers such as nurses in psychiatric hospitals and nursing homes, social service workers, elementary and secondary school teachers, retail workers, bus drivers, and in public safety and corrections.

In the United States, the vast majority (85%) of workplace homicides are type I violence (criminal intent), while only 3% of workplace homicides are type II violence (customer/client), 7% are type III violence (worker-on-worker), which continues to be emphasized by the media, and 5% are type IV violence (Peek-Asa et al., 2001).

Role Of Surveillance

The role of WPV surveillance is to provide data on the number and rate of workplace violence with respect to time, place, occupation, industry, and circumstances. Surveillance helps identify high-risk workers and their risk factors in order to focus resources for prevention. Surveillance also provides data to evaluate the success of prevention efforts by estimating the change in the number and rate of WPV incidents over time among high-risk occupations. Surveillance data systems have traditionally come from law enforcement crime reports, labor statistics, workers’ compensation records, hospital emergency records, and vital statistics records (coroner reports, death certificates, and other sources).

Challenges persist in surveillance of both work-related violent deaths and injuries caused by definitions of work relatedness for work-related homicides, and the absence of central reporting systems for nonfatal violent injuries (Peek-Asa et al., 2001). Traditional sources for nonfatal assaults such as workers’ compensation records, physicians’ records, or employees’ reports often fail to capture events related to violent crime that are not necessarily linked to criminal activity. Police records may fail to identify victims who are employees and therefore work relatedness is difficult to ascertain. Additionally, nonfatal events may be significantly underreported to authorities.

Risk Factors

Risk factors vary depending on the occupation and type of violence. Two examples are discussed below, retail workers who have a high type I homicide risk, and health-care and social service workers who have high type II and III nonfatal violence risk.

Late-Night Retail

The risk of robbery-related assaults is a problem in occupations requiring the handling of cash such as among retail workers. Additionally, female retail employees are at risk of sexual assault, which occurs more often in business establishments with a history of robbery and frequently involves a female clerk alone in a store at night.

Risk factors for late-night retail robbery (OSHA, 1998) include:

- Contact with the public;

- Exchange of money;

- Delivery of passengers, goods, or services;

- Working alone or in small numbers (pertains to taxicab drivers but not small grocery stores);

- Location of a store in high-crime areas or in close proximity of an expressway;

- Lack of natural surveillance due to poor environmental design (e.g., poor visibility into the store from the outside, and outside the store from inside, high shelf height providing places to hide and block visibility within the store, no mirrors, noncentralized placement of cash register, and easy access to escape routes);

- Lack of administrative or work-practice controls (e.g., no training of employees in crime prevention, no cash handling procedure to minimize amount of cash on hand, no use of a drop safe to deposit cash, an employee providing resistance, or use of weapons during a robbery;

- Lack of security equipment (e.g., no bullet-proof enclosures or closed circuit TV surveillance equipment).

Health Care And Social Service

Lanza (2006) noted that violence in health-care settings, particularly to nurses, is a problem internationally. Violence against nurses has been documented in the United States, Europe, China, Japan, India, Africa, Mexico, South America, New Zealand, and Canada. Risk factors that predispose health-care and social service workers to increased risk of assault (OSHA, 2004) include:

- The prevalence of handguns and other weapons among patients, their families, or friends;

- The increasing use of hospitals by police and the criminal justice system for criminal holds and the care of acutely disturbed, violent individuals;

- The increasing number of acute and chronic mentally ill patients being released from hospitals without follow-up care;

- The availability of drugs or money at hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies, making them likely robbery targets;

- Unrestricted movement of the public in clinics and hospitals and long waits in emergency or clinic areas that lead to client frustration over an inability to obtain needed services promptly;

- The increasing prevalence of gang members, drug or alcohol abusers, trauma patients, or distraught family members;

- Low staffing levels during times of increased activity in psychiatric hospitals such as meal times, visiting times, and when staff are transporting patients;

- Isolated work with clients during examinations or treatments;

- Solo work, often in remote locations with no backup or way to get assistance, such as communication devices or alarm systems or in high-crime settings;

- Lack of staff training in recognizing and managing escalating hostile and assaultive behavior;

- Poorly lit parking areas.

Prevention Approaches

Three types of WPV prevention strategies (legislative, administrative and behavioral, and environmental design approaches), are discussed in the following sections.

Legislative And Regulatory Approaches

Laws and regulations when enforced have worked to increase compliance to administrative, behavioral and environmental preventions and have resulted in reductions of robbery-related homicides and assaults in retail and taxicab industries. Federal, state, or provisional or local legislation when enforced can be a WPV deterrent.

Administrative And Behavioral Approaches

Runyan et al. (2000) defined administrative and behavioral interventions as ‘‘those directed at altering management practices (e.g., pre-placement screening, staffing patterns), worker practices (e.g., conflict management, restraint and control strategies), or both, for preventing workplace violence’’ (Runyan et al., 2000). Their definition excluded interventions that focus on modifying the physical work environment, which is reviewed in the next section. In their review of the literature, Runyan et al. (2000) applied the Haddon Matrix approach and categorized proposed administrative and behavioral interventions into pre-assault, during assault, and post-assault events. Although a wide variety of administrative and behavioral approaches to workplace violence prevention have been suggested and are frequently employed in the workplace, Runyan et al. (2000) concluded that few have been adequately evaluated.

Environmental Design Approaches

For over 20 years, the approach to prevent type I robbery-related assaults among retail workers in which taking money is the primary motive has been crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED). The CPTED model has been well accepted and recommended by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, made part of some state and local ordinances in the United States, and is the basis of U.S. convenience store industry guidelines.

The CPTED model recognizes that robbery risk can be reduced by modifying the business environment through application of four elements: Natural surveillance, access control, territoriality, and activity support. Natural surveillance includes increasing and balancing internal and external lighting such that visibility into the store is clear from the outside and vice versa. This creates a fish-bowl effect to give potential robbers the perception of being watched. These designs include central location of the cash register; clear view of the gas pumps, parking lot, and street from the register; clear view of the cash register from the outside premises; no signs blocking the windows; and clear view of all aisles, requiring low aisle height and corner mirrors.

Access control refers to the number of entrances, door placement, design of store to control customer movement, and access routes off the property. Ease of access and escape routes should be modified to increase natural surveillance by fencing off escape routes requiring exit from the parking lot in clear view of the register, fencing off access to trash dumpsters, etc.

Territoriality includes location of the store within the community, traffic flow surrounding the store, signs and advertisements for the store, and design issues that empower the employees over the perpetrators. Examples are not locating the establishment near access to major expressways and high-crime areas, and use of security features to protect employees, such as bullet-proof glass and pass-through windows, drop safes and cash minimums, signage advertising cash limits, and camera and closed-circuit TV systems to aid in capture of robbers. Activity support includes features that increase the presence of customers and traffic flow in order to increase natural surveillance.

Approaching Occupational Injuries And Workplace Violence From Multiple Levels

Occupational injuries and workplace violence exert too large a toll on the worldwide workforce. Improvements require concerted and consistent efforts from multiple parties and levels. Individual employers ultimately are responsible for providing safe work environments. However, employer efforts need to be complemented by efforts from organizations with overlapping interests, such as trade unions and other labor groups, manufacturer groups, standards setting bodies, government agencies, and researchers. Particularly vulnerable workers and those at differentially high risk merit attention. Some such groups can be identified globally (e.g., young and elderly workers, agriculture and construction sectors) and some vary by country or region (e.g., informal sector, unprotected workers, workers at risk of violence). There is potential and value for cooperative and collaborative efforts at the community, regional, national, and global levels.

Bibliography:

- Barnett RL and Brickman DB (1986) Safety hierarchy. Journal of Safety Research 17: 49–55.

- Concha-Barrientos M, Nelson DI, Fingerhut M, Driscol T, and Leigh J (2005) The global burden due to occupational injuries. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 48: 470–481.

- Haddon W (1968) The changing approach to the epidemiology, prevention, and amelioration of trauma: The transition to approaches etiologically rather than descriptively based. American Journal of Public Health 58: 1431–1438.

- Hagberg M, Christiani D, Courtney TK, et al. (1997) Conceptual and definitional issues in occupational injury epidemiology. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 32: 106–115.

- Lanza M (2006) Violence in Nursing. In: Kelloway EK, Barling J, and Hurrell JJ (eds.) Handbook of Workplace Violence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (1996) Violence in the Workplace: Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies. Cincinnati, OH: US Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and PreventionDHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 96–100.

- New York State Department of Health (2005) Teenage Farm Worker Dies During Silage Defacer Entanglement. Albany, NY: New York State Department of Health Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation (FACE) Program Report No. 05NY001.

- OSHA (1998) Recommendations for Workplace Violence Prevention Programs in Late-Night Retail Establishments. Washington, DC: OSHA3543.

- OSHA (2004) Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Health Care and Social Service Workers. Washington, DC: OSHA3148–01R.

- Peek-Asa C, Runyan C, and Zwerling C (2001) The role of surveillance and evaluation research in the reduction of violence against workers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 20: 141–148.

- Runyan C, Zakocs RC, and Zwerling C (2000) Administrative and behavioral interventions for workplace violence prevention. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 18: 116–127.

- Stout N (2001) The relevance of occupational injury research. Injury Prevention 7: 1–2.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.