This sample Orphans Due to AIDS Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

In 2005, the United Nations Development Programme Report stated that ‘‘the HIV/AIDS pandemic has inflicted the single greatest reversal in human development.’’ The infants, children, and adolescents who have been orphaned as a consequence of this epidemic are an important aspect of this reality. Their full development as human beings has been and is being jeopardized. A greater commitment of human, material, and financial resources is urgently needed to address the health and well-being of this population of children.

The Global HIV/AIDS Pandemic And Orphaned And Vulnerable Children

Patterns of illness, human rights abuses, and orphanhood that characterize the global HIV/AIDS pandemic are not forged by chance. Rather, poverty and economic inequities, the absence of educational opportunities, exploitative child labor, and pervasive violations of women’s and children’s rights produce the patterns of human suffering that are the subject of this research paper. A multitude of problems challenge children who are orphaned as a consequence of HIV/AIDS. While the problem of AIDS and orphans is most acutely experienced in sub-Saharan Africa, analysis of the patterns of suffering and their sources there may yield insights critical for devising effective public health strategies to alleviate both local and global suffering caused by the HIV/AIDS pandemic in other countries.

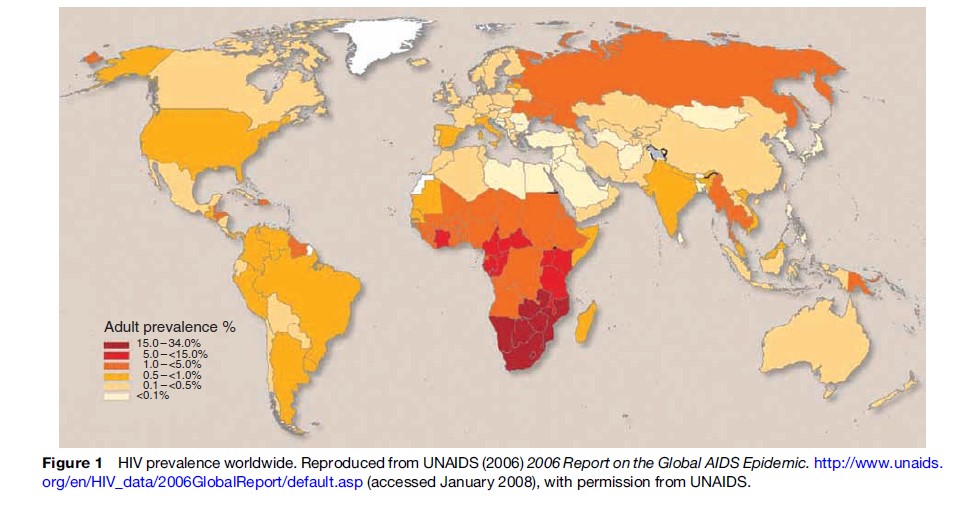

As of 2006, an estimated 39.5 million people are living with HIV, approximately 4.3 million are newly infected, and 2.9 million died in 2006 (see Figure 1). While HIV prevalence has leveled off in some countries, it is increasing at rates that far surpass initial predictions in others; thus, the overall number of people living with HIV is increasing. The pandemic has generated increased morbidity and a precipitous fall in life expectancy and birth rates, which has significant ramifications for child, community, and country development.

On average, almost one in three pregnant women receiving care at antenatal clinics in southern Africa is HIV infected. Young women aged 15–24 are two to six times more likely to be infected than men of the same age. In spite of the advances in treatment access, only 20% of people with advanced disease (1.3 million) are receiving needed antiretroviral treatment. Best estimates state that the median lifespan of HIV-infected women is 9 years. Maternal death has profound implications for infants, children, and adolescents; infants and young children in particular are at increased risk of dying.

Problems such as war, famine, and infectious disease outbreaks have produced large numbers of orphaned children. However, orphanhood is becoming a chronic condition of childhood with ramifications for adulthood because of the magnitude, morbidity, and mortality of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Nowhere is this chronic condition more apparent than in sub-Saharan Africa, home to 24 of the 25 countries with the highest HIV prevalence rates globally.

Prevalence Of Orphaned And Vulnerable Children

A commonly used definition of ‘orphan’ is a child whose parents died before the child reached the age of 15. However, there are problems with this definition. Adolescents beyond 15 years of age have needs and require adult support. A definition of child orphans that used the language of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which defines a child as anyone 18 years of age or less, would include this vulnerable population of 15 to 18-year-olds. There are cultural nuances in the use of the term ‘child orphan.’ For example, in some African countries, an orphan is a destitute child, regardless of whether he or she has a mother or father or both who have died. Finally, there is the issue of who is counted as a child orphan. Some agencies and studies only count orphans as children who have lost their mothers (i.e., maternal orphans), not their fathers (i.e., paternal orphans). However, some researchers would argue that maternal orphans become virtual double orphans (i.e., those who have lost both parents) because some fathers in this situation, while not dead, are not present and actively contributing to the care of the children.

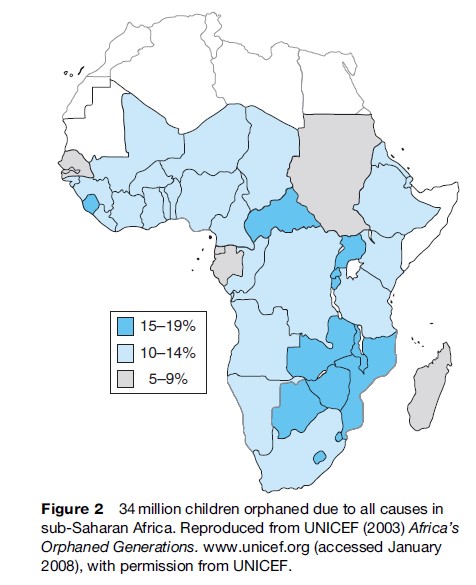

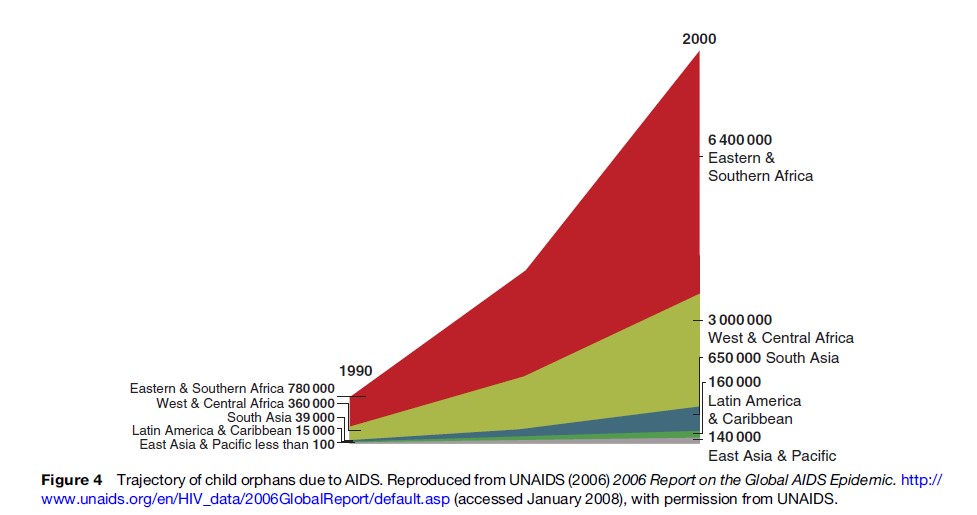

In spite of these shortcomings, the above definition is the most commonly used. Without HIV/AIDS, the number of double orphans would have declined from 1990–2010. Instead, it will triple. As of 2003, an estimated 15 million children under 18 years of age have been orphaned by HIV/AIDS worldwide, and 12 million of these live in sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 2). In comparison, there are 320 000 orphans in the United States. Overall, 9% of children in sub-Saharan Africa have lost at least one parent to AIDS; however, in Zambia and Swaziland, 25% and 35% of children, respectively, have lost at least one parent. Orphanhood due to HIV/AIDS is accounting for a greater proportion of all orphans worldwide. In 2001, 32% of all orphans in sub-Saharan Africa lost their parents to HIV; this has increased to 50%. In 11 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, 75% of parental deaths are due to AIDS. Another disconcerting phenomenon is the estimated ten-year or longer time lag between peak HIV prevalence and peak orphanhood. Thus, even when HIV rates stabilize or decline, the numbers of orphans will continue to rise for at least a decade.

In four countries outside sub-Saharan Africa, orphan prevalence is greater than 10%: Haiti, Afghanistan, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, and Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. However, unreliable or nonexistent data from these and other countries prevents accurate estimates of the number of orphans due to AIDS.

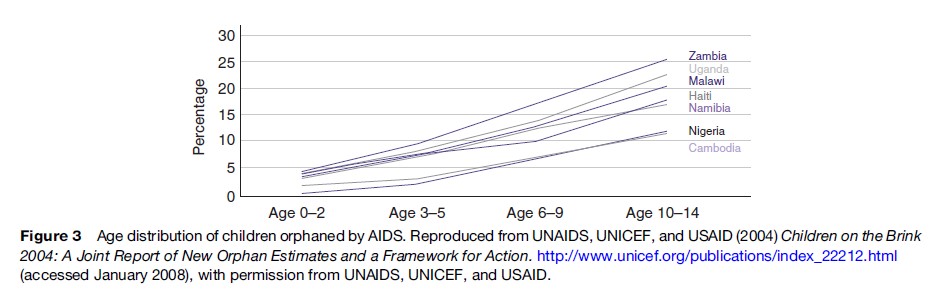

Surveys suggest that overall approximately 15% of orphans are 0–4 years old, 35% are 5–9 years old, and 50% are 10–14 years old (see Figure 3). Each one of these age groups faces unique risks to their health and well-being. Double orphans are more at risk than single orphans. And HIV-infected children who are orphaned suffer the double burden of being afflicted with the same illness that claimed the life of one or both of their parents.

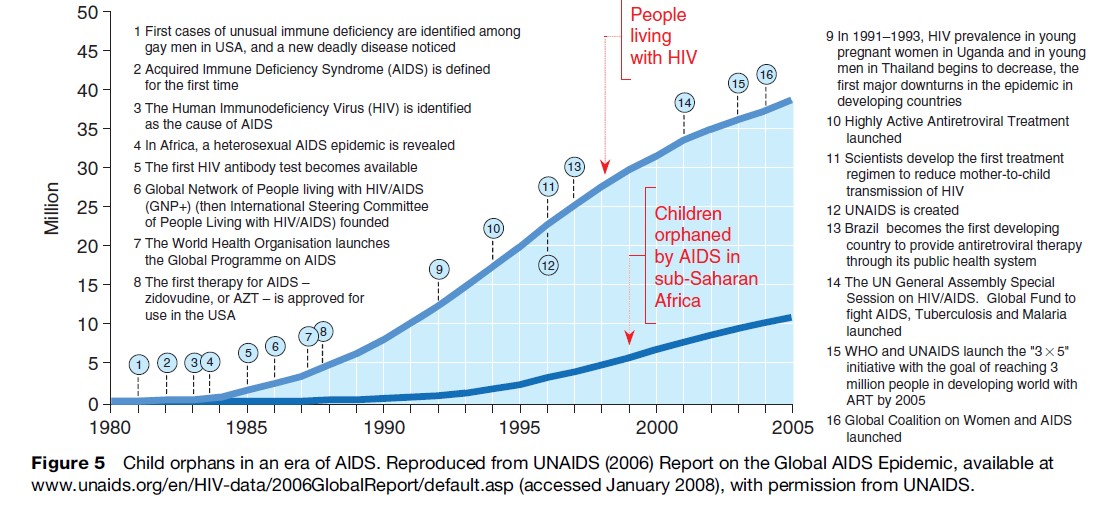

Although there are many problems with current models of measuring the scope of orphan prevalence, it is known that the relationship between HIV prevalence, orphan prevalence, and effects on family, community, and societal structures will change as the pandemic progresses. If rates of infection continue at their current pace, the prediction is that there will be 20 million orphans due to AIDS in Africa by 2010 (see Figures 4 and 5). The number of double orphans is expected to account for half of these. According to UNICEF, in light of current trends, the countries that will have the highest proportion of child orphans will be Lesotho, Swaziland, Botswana, and Zimbabwe, and greater than 80% of these children will be orphaned as a consequence of AIDS.

Vulnerabilities Of Orphaned Children

One of the first vulnerabilities that children face is whether they will be cared for, and by whom (e.g., other adults or children). A study of families in Zimbabwe found that important factors in the decision to care for orphans were social relatedness and financial capacity. Caregivers were more open to fostering children if the child was a relative (75%) rather than a friend’s child (50%) or a stranger’s child (25%). Data from UNICEF demonstrate that the majority of AIDS orphans (90%) are being cared for by extended families (e.g., grandparents, aunts, uncles). Currently in sub-Saharan Africa, 1 in 5 households with children care for at least one orphan.

Another issue is the quality of care, both material and psychological, that child orphans receive.

In addition to not being the healthiest option for children, placement in orphanages is not culturally appropriate or financially feasible in many countries (in some countries, orphanages do not exist). For example, Zimbabwe has 800 000 orphans, and less than 4000 are housed in 45 residential centers. But the reality is that many families, especially those headed by grandparents who are no longer economically active, are financially destitute. Household out-of-pocket spending is the largest single component of HIV/AIDS expenditure in Africa, greater than the amount of money contributed by governments and nongovernmental organizations.

AIDS is causing a deepening of poverty that affects all children, regardless of age. Child orphans are more likely to live in large, female-headed households with little income. In some households with at least one HIV-positive person, the income is half of similarly sized households in which HIV is not present. Some HIV-affected households spend up to four times more money on health care and use 30% of their income on funerals, while food consumption decreases as much as 40%. For infants, this poses a grave risk for malnutrition and accompanying acute morbidity and mortality. Recent studies have shown that children under 5 years of age living with an HIV-positive mother have higher mortality rates one year prior to and one year after the death of the mother, even after controlling for potential perinatal transmission. For households with orphans, there is an increased ‘dependency ratio’; in other words, fewer people are economically active in the face of a greater number of household members.

Children possess unique psychological and emotional needs. With the loss of biological parents comes a disruption in the parent–child relationship. And even though a family may take in a child, he or she may be forever viewed as an outsider and less valued than the other members of the family. Some children may have family members who help them through their bereavement. But it is also quite possible that family members are so consumed with finding food, clothing, and shelter that they do not have sufficient time to help children or adolescents who may be struggling emotionally. Adolescent orphans demonstrate heightened anxiety and higher rates of depression and anger than their non-orphaned counterparts. For some children, their bereavement is increased because they have been separated from their siblings. In addition, children face stigma and discrimination because they are assumed to be infected. Younger children in particular, who may not understand the disease process, suffer the loss of friendships, and are at risk of physical, verbal, and psychological abuse. Stigma, in many contexts, perpetuates the epidemic and results in more affected children.

Rapid disintegration of their family can leave children at a loss regarding how to function in the world. In Africa in particular, a child’s social, spiritual, and moral development and ultimate place in society are determined in large part by the family and kin. Disintegration of families results in disintegration of social capital (social relationships that facilitate community action for the mutual benefit of members) within communities.

For older children, the risk of death is much less than infants, but the risk of not receiving a formal education is quite high. In some cases, the teachers are ill or caring for ill relatives and thus are unable to teach; this affects all children, orphaned or not. Or the family caring for the orphaned child cannot afford to send that child to school. In the case of adolescents, they may be required to care for relatives and siblings or find work to support the family, and thus must forego education. Currently only 64% of children in Africa and 83% in Asia are enrolled in primary schooling. Given current trends of increasing numbers of orphans, it is likely that fewer children will attend school. For those who are able to attend school, the challenges do not abate. A study of five countries in sub-Saharan Africa found that children who had lost one or both parents were significantly less likely to be in the appropriate grade for their age. Knowing what a critical role early child development and literacy play as social determinants of health, lack of schooling will result in worsening overall health for these children and adolescents.

A child less than 18 years old heads approximately 1% of households. However, orphans living alone or in youth-headed households are becoming more common. A study in Zimbabwe found 5% of caregivers were in their teens. In some cases, they may still have contact and receive support from relatives, but in other cases, the opposite is true, and youth feel isolated, marginalized, and rejected. Adolescents are sometimes expected to assume the role of parents, but without the requisite rights given to adults. In the face of inaccessible, overburdened, underdeveloped judicial systems that do not recognize child rights, they are at risk of losing their inheritance and property. Adolescent orphans initiate sex earlier than non-orphans, thereby putting themselves at risk for pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases.

Given the dire economic situation that many families face, children are expected to start working, many times in unjust, dignity-impugning labor. An International Labor Organization (ILO) study in Tanzania found that 70% of self-employed children, 60% of child domestic workers, and 55% of child sex trade workers lost parents to AIDS. A study in Zambia revealed that the average age of children engaged in sex work was 15 years. Three-quarters of these young people had lost one or both parents to HIV/AIDS. They said they engaged in prostitution because they and their families needed money. There are no clear estimates on the number of children living on the street as a consequence of being orphaned. However, one study in Zambia demonstrated that 58% were due to loss of parents. Children become the victims of popular myths regarding HIV prevention (e.g., that an HIV-positive man can cure himself by having sexual intercourse with a young virgin) and face sexual exploitation, with its concomitant risks of pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.

A Public Health Response Informed By Human Rights Principles

As the UNAIDS Director Dr. Piot points out, the exceptional nature of AIDS requires an exceptional response and that includes responding to the rights of infants, children, and adolescents. Unfortunately, there is a lack of public discourse on how this pandemic has negatively affected the lives of millions of children.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) provides a cogent blueprint for how to establish national policies that are formulated with the best interests of the child in mind, that protect against discrimination, and that strive to promote a child’s right to survival. One critical principle in the UNCRC is the responsibility of individual governments and the international community to provide assistance to parents, guardians, and communities as needed. An analysis of reported funding for the 17 most affected countries in sub-Saharan Africa in 2003 found that $200–300 million was earmarked for orphans and vulnerable children due to the HIV/AIDS pandemic. In the case of U.S. funding, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) contributes 3% of its total budget (approximately $50 million) to orphans and vulnerable children programs in its 15 focus countries, with approximately half to four of the focus countries (Ethiopia, Mozambique, Uganda, and Zambia). While these efforts are laudable, they are not directed at the countries with the highest prevalence of child orphans due to AIDS. Given the tremendous financial burdens faced by countries most severely hit by HIV/AIDS, increased funding and coordinated support from the international community is absolutely essential. Monitoring is also critical so that obstacles preventing appropriate distribution to communities are overcome.

In spite of the pressing physical, mental, social, moral, and spiritual issues facing children as a consequence of AIDS, their overall care in this pandemic is woefully neglected. An initial attempt to begin to address these issues occurred at the 2001 United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS), when heads of state made a Declaration of Commitment to address the needs of orphans due to HIV/AIDS. However, in 2003, only 6 of 46 (13%) sub-Saharan African countries had a national policy on orphans and vulnerable children in place (another 20% were in the process of formulating a national policy); less than one-third of poverty reduction strategy papers and national HIV/AIDS plans mention the issue of children affected by AIDS; and only Cameroon had proposed any child-focused initiatives. Currently, less than 10% of children orphaned as a consequence of AIDS are receiving support services, mostly in the form of material, rather than psychological, support.

In March 2004, UNAIDS and collaborating organizations devised a blueprint for care, Framework for the Protection, Care, and Support of Orphans and Vulnerable Children Living with HIV and AIDS, which focuses on five areas: strengthening the capacity of families to protect and care for orphans and vulnerable children by prolonging the lives of parents and providing economic, psychosocial, and other support; mobilizing and supporting community-based responses to provide immediate and long-term support to vulnerable households; ensuring access for orphans and vulnerable children to essential services, including health care, education, and birth registration; ensuring that governments protect the most vulnerable children through improved policy and legislation and by channeling resources to communities; and raising awareness at all levels through advocacy and social mobilization to create a supportive environment for children affected by HIV/AIDS.

Strategies to assist children need to be directed upstream and downstream. The global AIDS pandemic is undermining the medical, economic, and social structures of many societies. Health systems in general are overburdened and underfinanced to care for patients with HIV/AIDS. Money that is directed to these patients is diverted from other lifesaving child health programs like immunizations and treatment for pneumonia and diarrheal infections. A basic tenet of the UNCRC is that children have a right to the highest attainable standard of health; governments are obligated to work to decrease infant and child mortality and to provide appropriate pre and postnatal care to women. Knowing that the proportion of child deaths due to HIV infection is rising, and that a child’s risk of death increases dramatically if the mother dies, it is incumbent upon governments to act accordingly. Women have the right to appropriate treatment to increase their longevity and quality of life. A secondary benefit is that healthy women will have healthy children.

Children have a right to a standard of living adequate for their physical, mental, spiritual, moral, and social development. Implicit here is the right to water, sanitation, housing, a safe home, and other basic needs. Once again, governments have a responsibility to provide for families if the families cannot make ends meet to fulfill this right. The extensive kinship network that is caring for orphaned children in Africa is to be applauded for its demonstration of true community involvement. They have put into practice the adage, ‘‘It takes a village to raise a child.’’ Nonetheless, these networks are fragile and at risk of collapsing under the burgeoning weight of having more children to provide for without the requisite support from adult wage earners and the government. Also, for cultural reasons and issues of stigma, these networks are not universally present. In response to this, successful community-based orphan visiting programs have been in place as early as 1996 in sub-Saharan Africa. Community members are trained in HIV/AIDS, stigma, discrimination, and child health and development needs and then make regular visits to children orphaned by AIDS, whether they are living with a family or in a local group home. For the few countries that have them, there is an urgent need to close national orphanages and divert the funds into such community-based centers and families caring for orphans.

For women and men who are infected or have active disease, in addition to provision of medications, a holistic approach that addresses the needs of the entire family is warranted, for example, increasing funding to make all households food-secure, to provide adequate shelter, and to make education affordable and accessible to all children. The penchant for ‘targeted’ interventions and narrow funding streams risks thwarting this approach. Also, giving only children food results in resentment and the unwanted effect of people wanting to declare relatedness to an HIV-infected person so that they receive assistance. Training people (e.g., psychologists, social workers, church and tribal leaders, as culturally appropriate) who can help facilitate discussion among family members about what it means to live with a chronic and ultimately fatal illness and can help families plan for future events (e.g., the loss of one or both parents) can improve the mental health of the household. Having people who are specially trained to work with children will address their unique needs based on their level of development.

The right to education contributes to a child’s holistic development. A school setting may be the place where most children receive necessary health education, including education about pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease prevention, which is vitally important in the era of AIDS. A study in Zimbabwe found that the most important resource requested was educational subsidies. Free, universally available, and accessible primary schooling needs to be present in all countries. If not, and if children and adolescents are forced to work, ultimately, community and country development will flag considerably.

The national orphan policy of Botswana is successfully based on the UNCRC. The Kgaitsadi Society in Gabarone is an example of a community organization designed to care for and educate AIDS orphans. Begun in 2002, it addresses children’s basic material needs and provides primary schooling using a flexible model of basic education. The Society also provides support for children caring for other family members and for those who are working.

The parents of many older children and adolescents have died before being able to pass on skills such as farming and animal husbandry. Therefore, job skills training and life skills training for these children are critically needed to increase their options for meaningful, non-exploitative employment and to secure their livelihoods as adults. A joint effort of the World Food Programme and the Food and Agriculture Organization is the Junior Farmer Field and Life Schools. To date, 34 schools benefiting close to 1000 young people ages 12–18 have been set up in Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia, Tanzania, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe. The schools teach traditional and modern agricultural methods, as well as HIV/AIDS awareness and prevention, gender sensitivity, sexual health, nutritional education, and business skills. The schools provide psychological and social support, which helps young people develop their self-esteem and confidence.

It is important to remember that there are other groups of vulnerable children, among them those who live with one or both HIV-infected parents (who will most likely be orphans in the near or distant future), those living in households that have taken in orphans, and those who are discriminated against because of the HIV status of their parents or themselves. Taking a child-centric, nondiscriminatory approach is required. Orphan status alone may not be the most important marker of vulnerability. Also, focusing only on orphan status may produce resentment, heighten stigma, and is unfair. A broad range of policies and programs need to be designed to assist all orphans (from all causes), children orphaned by AIDS, and other vulnerable children.

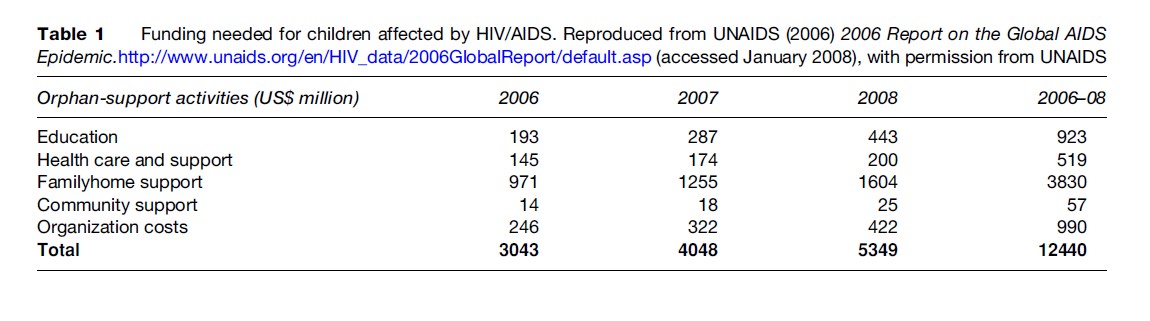

Funding can come from the international community and nongovernmental organizations (see Table 1). Also, individual governments should redirect the money they put toward debt relief into these vital services. Governments need to create and/or improve policies and legislation to protect, support, and strengthen children, families, and communities. Government-sponsored public service announcements and school-based programs can raise awareness and eliminate stigma. And social services need long-term funding commitments from governments and the international community to ensure access. Communities must be involved in the discussion, invention, and implementation of programs for their children. A focus on the futures of children growing up during this pandemic will prevent a generation of ill, malnourished, illiterate, exploited, poor youth at risk of early death. The response requires exceptional dedication, leadership, and resources.

Bibliography:

- Andrews G, Skinner D, and Zuma K (2006) Epidemiology of health and vulnerability among children orphaned and made vulnerable by HIV/ AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Care 18(3): 269–276.

- Atwine B, Cantor-Graae E, and Bajunirwe F (2005) Psychological distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Social Science and Medicine 61(3): 555–564.

- Bicego G, Rutstein S, and Johnson K (2003) Dimensions of the emerging orphan crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science and Medicine 56(6): 1235–1247.

- Bonnell R, Termin M, and Tempest F (2004) Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers: Do They Matter for Children and Young People Made Vulnerable by HIV/AIDS? New York: UNICEF/World Bank.

- Crampin AC, Floyd S, Glynn R, et al. (2003) The long-term impact of HIV and orphanhood on the mortality and physical well-being of children in rural Malawi. AIDS 17(3): 389–397.

- Dabis F and Ekpini ER (2002) HIV-1/AIDS and maternal and child health in Africa. Lancet 359: 2097–2104.

- DeWaal A and Whiteside A (2003) New variant famine: AIDS and the food crisis in southern Africa. Lancet 362: 1234–1237.

- Drew RS, Makufa C, and Foster G (1998) Strategies for providing care and support to children orphaned by AIDS. AIDS Care 10(supplement 1): S9–S15.

- Ekpini RE and Gilks C (2005) Antiretroviral regimens to prevent HIV infection in infants. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 87 (3): 483.

- Foster G (2005) Bottlenecks and dripfeeds: channeling resources to communities responding to orphans and vulnerable children in Southern Africa. London: Save the Children (UK).

- Foster G (2006) Children who live in communities affected by AIDS. Lancet 367: 700–701.

- Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, et al. (2005) HIV infection, reproductive health in teenage women orphaned and made vulnerable by AIDS in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care 17(7): 785–794.

- Grassly NC, Phil D, and Timoeus IM (2005) Methods to estimate the number of orphans as a result of AIDS and other causes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 39: 365–375.

- Howard BH, Phillips CV, Matinhure N, Goodman KJ, McCrudy SA, and Johnson CA (2006) Barriers and incentives to foster care in a time of AIDS and economic crisis: a cross-sectional survey of caregivers in rural Zimbabwe. Boston Medical Center (BMC) Public Health 6: 27.

- Matshalaga NR and Powell G (2002) Mass orphanhood in the era of HIV/ AIDS. British Medical Journal 324: 185–186.

- Miller CM, Gruskin S, Subramanian SV, Rajaraman D, and Hyemann J (2006) Orphan care in Botswana’s working households: Growing responsibilities in the absence of adequate support. AJPH. 96: 1429–1435.

- Monasch R and Boerma JT (2004) Orphanhood and childcare patterns in Sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of national surveys from 40 countries. AIDS. 18(supp 2): S55–S66.

- Onyango P and Lynch MA (2006) Implementing the right to child protection: a challenge for developing countries. Lancet 367: 693–694.

- President Bush’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief: Aid to Orphans and Vulnerable Children. Washington, DC: Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator. http://www.state.gov/s/gac/rl/fs/46726.htm. (accessed January 2007).

- Ruland CD, Finger W, Williamson N, et al. (2005) Adolescents: Orphaned Vulnerable in the Time of HIV/AIDS. Youth Issues Paper 6. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADE223.pdf. (accessed August 2006).

- Sarker M, Neckermann C, and Muller O (2005) Assessing the health status of young AIDS and other orphans in Kampala, Uganda. Tropical Medicine and International Health 10(3): 210–215.

- Thurman TR, Snider L, Boris N, et al. (2006) Psychosocial support and marginalization of youth-headed households in Rwanda. AIDS Care 18(3): 220–229.

- UNAIDS (2006) Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. http://www. unaids.org/en/HIV_data/2006GlobalReport/default.asp (accessed January 2008).

- UNAIDS, UNICEF, USAID (July 2004) Children on the Brink 2004: A Joint Report of New Orphan Estimates and a Framework for Action. http://www.unicef.org/publications/index_22212.html (accessed January 2008).

- UNICEF (2003) Africa’s Orphaned Generations. unicef.org (accessed January 2008).

- UNICEF, UNAIDS (2004) Framework for the Protection, Care, and Support of Orphans and Vulnerable Children in a World with HIV and AIDS. (accessed August 2006).

- http://www.unicef.org/uniteforchildren – UNICEF, Unite for Children Unite Against AIDS.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.