This sample Patient Empowerment in Health Care Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

Empowerment is a term widely applied today in many domains of our lives. As such, it has been the focus of scholarship in various academic disciplines including psychology, sociology, education, economics, and community/organizational development. In recent years, the concept of empowerment has been the subject of great interest in the health-care context, especially given the many power imbalances that exist in medicine. While physicians have traditionally held considerable power – both over the patient in the consultation room and over other health-care workers in health-care facilities – recent trends toward centralized decision making and cost containment have disrupted the traditional, physician based power structures, leading to a situation in which they too now seek power.

Given both the traditional and modern power imbalances, for a health-care system to function correctly, both clinicians and patients need to be empowered and, more importantly, need to interact in an environment of mutual respect and partnership. This implies that health-care providers maintain sufficient power to fulfill their professional obligations to multiple constituencies, including the patients and communities they serve. With this power comes responsibility, as providers must share this knowledge while maintaining patient autonomy. Likewise, patients, their advocates/support networks, and families need power to realize their preferences and health-related needs and to fulfill their responsibilities both within and transcending the traditional doctor/patient dyad.

Empowerment Principles In Health-Care Literature

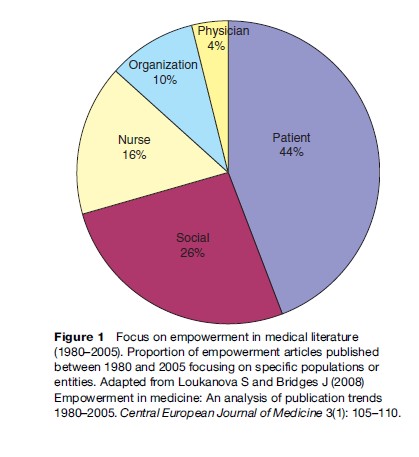

A recent review of the English language medical literature between 1980 and 2005, summarized in Figure 1, found a range of applications of empowerment principles in health care (Loukanova and Bridges, 2008). First, following more general social and political empowerment movements, 26% of all English language articles in the medical literature on empowerment have focused on issues of social empowerment, which relate to issues such as discrimination and health disparities. Second, research concerning nurse empowerment has been a major topic in health care, accounting for 16% of the literature. This body of work focuses on expanding nursing education, developing leadership and management skills, and fostering greater professional autonomy and job satisfaction. It also relates to the imbalances in professional power in the health-care workplace. Third, studies concerning the empowerment of organizations accounted for 10% of the literature. These papers have addressed issues such as improving staff performance, organizational culture, and the overall quality of the organization. Interestingly, there was very little research concerning the empowerment of physicians (only 4% of the literature). These articles focused on physicians’ need for power to fulfill and manage their professional responsibilities to achieve outcomes of improved work efficiency, patient satisfaction, and physician self-governance.

The most prominent topic in the literature on empowerment in health focused on patient empowerment, accounting for 44%, and while we touch briefly on other types of empowerment in this research paper, we focus primarily on issues related to patient empowerment. The promotion of patient empowerment is dependent upon changing both patients and the health-care system. While patient empowerment can be established by introducing more choice for patients it also requires a system that is more patient centered to facilitate such choice.

Empowerment As An Idea

At the core of the concept of empowerment is the idea of physical or legal power. The word power comes from the Latin word potere, which means ‘to be able’ or to have the ability to choose. The verb empower means ‘to give authority or power to; to authorize or give strength and confidence to.’ In terms of its general use, Webster’s dictionary defines power from a different perspective, citing the ‘ability to act or produce an effect.’ The concept of empowerment, however one defines it, seems to transcend its dictionary definition, representing a complex concept with a long and illustrious history. From an economic perspective, the roots of empowerment can be found during the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth century. The concentration of wealth in the ownership class was thrown into sharp relief by the effects of rapid industrialization and its effect on the class system. Empowerment evolved from the notion of increasing worker motivation and improving managerial leadership to the processes of giving subordinates greater resources and discretion today. Empowerment in the workplace is underpinned by Kanter’s structural theory of organizational behavior (1993), which states that the empowerment of staff is important to overall work effectiveness and job satisfaction.

In the twentieth century, empowerment became associated with the struggle of those who held the least power in society. This was especially true for minority groups, who were discriminated against on the basis of their religion, gender, or race, perhaps best illustrated by the Civil Rights movement in the United States. Since the 1970s, empowerment has also served as the basis for defending community interests and promoting the mutual participation relationship between doctors and patients in the context of the consumer movement. And today, empowerment has a broader meaning, which focuses on types of self-realization and mobilizing the self-help efforts of people, rather than simply providing them with social welfare.

Empowerment In Medicine And Health

For most in medicine the thought of power is often focused on issues of control and domination. Focusing only on these aspects of power, however, limits our understanding of empowerment as it relates to any application in society. That said, the modern interpretation of power is extremely varied, and has to be considered in light of its use in technology, physics, mathematics, statistics, religion, politics, feminism, civil rights, psychology, disability, and even medicine. Taking this into account, the power element of empowerment has the potential for extremely broad interpretations, and as such could be applied to a broad range of stakeholders in health care. Early empowerment movements in health focused on services for and attitudes toward people with disabilities and mental illness, incorporating both community action and national/state legislation aimed at preventing discrimination. In more recent years, empowerment has hit the mainstream – being the focus of national attention and debate for a broader patient population.

Zimmerman (1990, 1995) and Rappaport (1984, 1987) are two of the leading researchers in the development of empowerment theory in health care. Zimmerman (1990) conceptualized empowerment at three different levels: (1) psychological empowerment is empowerment at the individual level of analysis; (2) organizational empowerment represents improved effectiveness resulting from organizations successfully competing for resources, networking with other organizations, or expanding their influence; and (3) empowerment, at the community level, refers to individuals working together in an organized fashion to improve their lives collectively and create links among community organizations and agencies that help maintain quality of life. Zimmerman (1995) expanded on his theory by distinguishing between processes and outcomes. Empowering processes refer to how people, organizations, and communities become empowered, whereas empowered outcomes refer to the consequences of those processes. He argues that empowerment can take many different forms and is dependent on the context for which it is being defined.

Rappaport (1984) takes a more pragmatic approach, noting that empowerment is easier to define in its absence – that is, through the eyes of the unempowered. Rappaport argues that it is simpler to identify the powerless, and significantly more difficult to define empowerment positively. He argues that the empowerment concept provides a useful, general guide for developing preventive interventions in which the participants feel they have an important stake. He also argues that empowerment should be adopted as a guiding principle for community psychology (Rappaport, 1987).

Despite the challenges in defining empowerment in positive terms, it does have a tremendously positive connotation, belonging to a class of similar positive constructs that have emerged in the past 20 years (e.g., patient activation, self-efficacy, shared decision making, patient autonomy). Empowerment has been employed universally in the medical literature as a positive construct independent of the area of its application. Interest in empowerment in medicine now transcends its initial application in the psychology literature (Rappaport, 1984) to includes issues of organizational and clinical management (Loukanova et al., 2007). Empowerment has become an important concept in understanding individual-, organization-, and community-level development in health care, although a widely accepted definition of empowerment still remains elusive (Gibson, 1991).

Patient Empowerment

Medicine’s tradition of physician paternalism, in which physicians control much of the information and decision making, is currently giving way to one in which patients play a significant role in medical decision making in particular and their own health care in general. Concurrent with this trend have been continued calls for medicine to embrace patient-centered care and to better inform the patient, pay more attention to patientreported outcomes including patient preferences, and to focus more on patient satisfaction. In both academic and policy circles there has also be a great deal of interest in patient empowerment, which can be considered an umbrella term, encapsulating a vast array of processes and outcomes.

Exact definitions of patient empowerment vary, depending on the disciplinary backgrounds of scholars as well the target populations of interest. In the context of nursing practice and education, Gibson defines empowerment ‘‘as a social process of recognizing, promoting and enhancing people’s abilities to meet their own personal needs, solve their own problems and mobilize the necessary resources to feel in control of their own lives’’ (1991: 359). In their research with people with mental illness, Linhorst et al. define patient empowerment as ‘‘having decision-making power, a range of options from which to choose, and access to information’’ (2002: 472). According to Chamberlin (1997: 43), the key elements of empowerment in mental health are ‘‘access to information, ability to make choices, assertiveness and self-esteem.’’ In relation to health information, empowerment means that patients are able to take control of their own health care and to make informed decisions. In parallel literature, the term activated patient has also been used to refer to patients who actively participate in their health care through knowledge of disease and treatment options and acquisition of skills to manage their health status (Hibbard et al., 2004).

Types Of Patient Empowerment

The patient empowerment literature has focused on society in various ways, with subliteratures centered around individuals, families, or communities. Articles on individual patient empowerment focus on the relationship between the individual who receives medical attention and the health-care system, while articles on family empowerment take a broader perspective of care, involving other caregivers such as parents or spouses. Community empowerment encompasses a group of people living in the same locality, sharing a common disease, sharing ethnic or cultural characteristics, and taking action to improve their lives and to achieve greater equality of power (Figure 2).

Models Of Empowerment

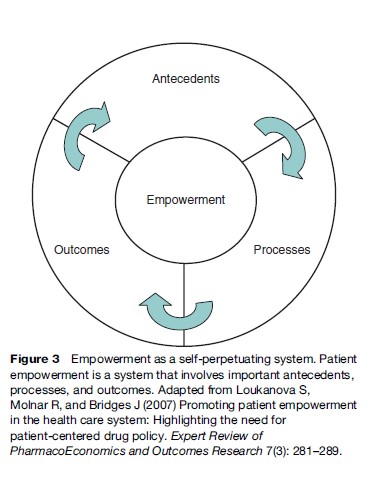

Existing conceptual models in the literature involve issues such as community empowerment (Menon, 2002), nursing empowerment (Gibson et al., 1991), or family empowerment. Population or disease-specific models have been published in the area of mental illness, brain damage (Man et al., 2003), trauma patients (Fallot et al., 2002), and diabetes (Anderson et al., 2000). In a recent review of the literature, Loukanova et al. (2007) presented a conceptual model of empowerment for application to a general patient population. Here, empowerment is understood as a continually evolving process based on antecedents, or the necessary elements that allow patients to start the empowerment process; processes that emphasize the interaction between patients and the health-care system; and outcomes for the individual patient. This model tries to identify what is common about the patient empowerment process across different patient groups. It is presented (Figure 3) as a cycle, based on the type of relationships between the elements and the concept of a continuum with which this process is characterized.

Antecedents to empowerment include knowledge, health literacy, patient initiative, and advocacy and access to services. Important processes of empowerment are information sharing, doctor-patient communication, choice, and shared decision making. Finally, patient empowerment aims not only to improve health outcomes, but to generate patient-centered care that will affect patient satisfaction, self-efficacy, and adherence.

Measuring Empowerment

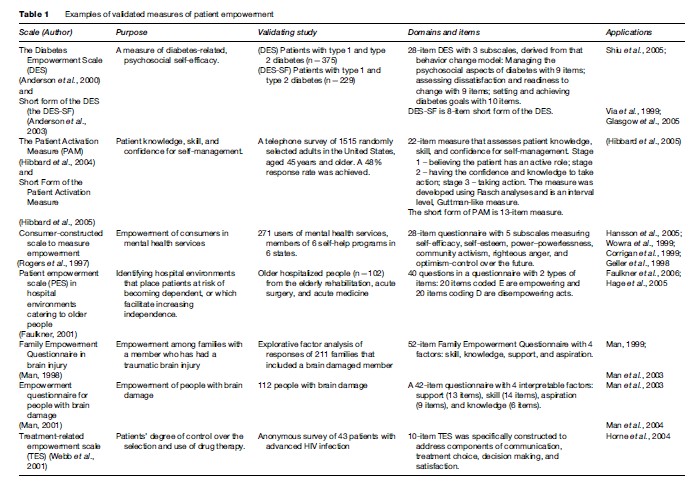

There are a number of instruments presented in the literature that attempt to measure patient empowerment, but they often focus on specific populations or diseases,

rather than the general population. Examples include the Family Empowerment Questionnaire (Man et al., 2003); the consumer-constructed scale in mental health services (Rogers et al., 1997); Diabetes Empowerment Scale (Anderson et al., 2000); Patient Activation Measurement (Hibbard et al., 2004), and the Therapeutic Alliance Scale (Kim et al., 2001) (Table 1). More research is needed to define in general the characteristics of the empowerment process that can serve as a basis for the development of a measure of patient empowerment in the general population.

A Holistic Model Of Empowerment

Parallel to this recent rise in empowerment, a number of health-care systems have sought to become more patient-oriented. In the United States, a backlash against managed care and the growing number of uninsured and underinsured individuals with limited access to health care has in part precipitated calls for a more consumer directed health-care system. In Europe, where there has been a long history of paternalism extending to medicine and where central agencies ration health care, there has also been an attempt to involve patients in medical decision making and introduce treatment options.

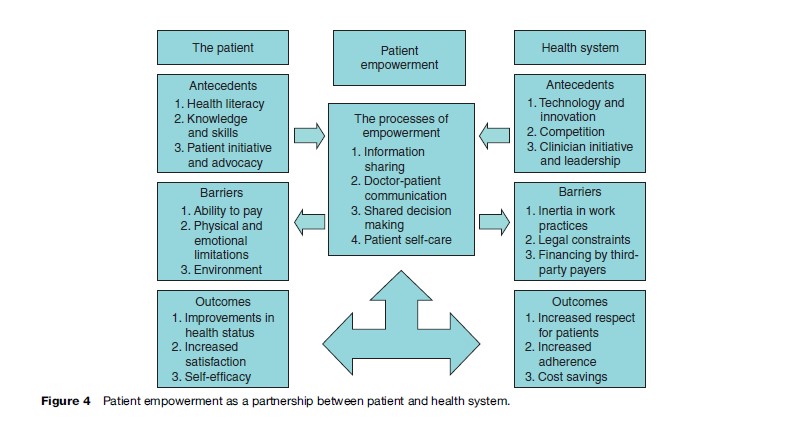

In this section, we present a holistic model of empowerment that focuses on both patient and provider (or system) aspects of empowerment. In this model, patient empowerment is understood as a joint process whereby patients and providers work in partnership to enhance patients’ involvement in their health and health care. This more complex system of empowerment brings together separate literatures on patient and provider empowerment, offering a more comprehensive account of empowerment. More importantly, the model highlights the role that the health-care system plays in patient empowerment. In this regard, patient empowerment is affected by all stakeholders of the health-care system including the state in its regulatory, financing, and purchaser role(s), and the profit and nonprofit sectors in financing, purchaser, and organizing roles. This model (Figure 4) also highlights some of the outcomes related to the fostering and promotion of empowerment for patients and providers.

Processes Of Empowerment In Health Care

With all that has been written about empowerment in health care, little attention has been paid to how empowerment influences or impacts the provision of care. Based on a review of the literature, there are four overlapping themes in the literature that can be considered key processes involved in the empowerment of the patient, namely: (1) information sharing, (2) doctor-patient communication, (3) shared decision making, and (4) patient self-care.

(1) Information Sharing

One of the principal processes of empowerment is information sharing, whether it is among patients, between the patient and physician, or with patients communicating with some external agency/advocate. Traditionally, information sharing efforts related to empowerment were based on grassroots and community programs, however, this has been affected dramatically by national public health campaigns (especially those using mass media), direct-to-consumer advertising, and by email and the Internet. While such broad-brush mechanisms prove to be a cost-effective method for information sharing, small-scale interventions and advocacy continue to play an important role in empowerment. Furthermore, mass media approaches to information sharing lack intimacy, partnership, and follow-up support that are synonymous with grassroots efforts.

For many, the easy availability of information has played an important role in transforming the doctorpatient relationship, while for others, it is a disruptive, potentially unempowering force. This bipolar view of information is best exemplified by the heated debate over direct-to-consumer advertising for pharmaceuticals (Gilbody et al., 2005), but it applies to any number of public health efforts that aim at changing patient behavior. It is certain that with better patient information comes patient responsibility, a responsibility that can be disruptive for many, leading some to classify information sharing as an antecedent to empowerment, rather than an activity of empowerment. Patient empowerment requires that patients are not just recipients of information – from only industry, providers, and government stakeholders communicating with the patient – but agents who can generate and process information. For true patient empowerment, patients need to inform the health-care system about their own situation – both in terms of their health and what they would like out of health care. For example, new technologies, such as home-based monitoring devices, aim to facilitate this empowering process Patients are able to possess real-time knowledge about their (chronic) conditions, which can then facilitate more balanced communication between them and their physicians.

Patients can also possess valuable information in other ways. Self-help groups offer a supportive mechanism for which individuals with similar needs or experiences can be both student and teacher. Also, disease-specific patient associations serve as a valuable meeting place for patients to share information. In the United States, Medicare and Medicaid programs have a specific objective of forming patients about their health-care opportunities – specifically aimed at promoting quality and price transparency.

(2) Doctor–Patient Communication

Focusing on the patient and the doctor, there has been an increasing emphasis on the transformation of the brief patient-doctor encounter into a lasting relationship with the mutual participation of both the patient and physician as the foremost goal. The active involvement of the patient is argued as a means by which problems inherent in health care (including information asymmetry between patient and physician and uncertainty) can be solved through honest and reasonable disclosure. As we move into an era of chronic illness, there is a growing need for better communication between doctor and patient. This interaction is impeded by time and resource constraints, language and cultural barriers, and by the notion (held by some patients and providers) that doctor knows best. While this latter notion has been reinforced by the professionalization of medicine over the past 100 years and the subsequent belief in informational asymmetries, it is also grounded in more ancient archetypes including tribal and religious convictions of the absolute power of the healer/redeemer (i.e., he or she who can give life also has the power to take it away).

Doctor-patient communication can serve both clinical and human needs. By necessity, such communication can be used to understand symptoms and patient histories, but more recently communication is used to understand the patient’s needs and to discuss the optimal treatment path – including introducing the patient to any self-care tasks that they must undertake. On the human side, doctor-patient communication builds rapport and trust, an environment of empathy, and leads to more satisfaction for all parties involved (although a mismatch of patient and physician communication styles might not lead to rewarding communication). Thus, doctor-patient communication is not only vital to informed choice, but it leads to both positive health and nonhealth outcomes for the patient (Pignone et al., 2005).

(3) Shared Decision Making

Given the level of complexity of decision making in modern medicine and the differences between different patients (whether they be caused by variation in disease staging, genetics, lifestyles, or preferences), a shared decision-making framework is becoming increasingly necessary in medicine and a vital step in the empowerment of patients. Here we use shared decision making as an umbrella term to cover the principle of joint, doctor-patient decision making (in the literal sense) and policies, programs, and decision aides that facilitate a thoughtful discussion of health-care options between physician and patient. Given that involvement of the patients in decision making not only has important consequences for their own care (and how he or she feels about it), but also impacts the effectiveness of public health efforts in screening, treatment, disease-control programs, and (potentially) medical costs, a number of agencies now promote active, shared decision making. Surprisingly, there are many who believe that individual patients do not want to be involved in the decision-making process – often sighting ignorance, fear, or cultural barriers. Others believe that if prompted and assisted by an external advocate, these potentially unwilling patients can quickly learn and adopt shared decision making. To encourage such patients to speak up in the medical decision-making process, a number of agencies (both in the profit and not-for-profit sector) offer information about treatment options and decision aides in a range of conditions. A leader in this area is the Ottawa Health Research Institute which has developed numerous ‘patient decision aids’ to help patients and their health practitioners make tough health-care decisions (O’Connor et al., 1999). These decision tools prepare patients to discuss their health care with physicians by informing them about the options and possible consequences, creating realistic expectations, or providing balanced examples of others’ experiences with decision making. Many patient groups now promote shared decision making, often using virtual support groups and storyboards/blogs to share patient experiences. These mechanisms foster doctor–patient communication by enlightening the patient to the various care paths and outcomes that other patients in their shoes have experienced.

(4) Patient Self-Care

One of the elements that best defines an empowered patient is patient self-care or self-management. Again, this encompasses a range of activities from patients triaging themselves to administering end-of-life pain management. It may involve preventative or behavioral change, or thorough self-management of medication for chronic diseases. Patient self-care may not necessarily place the patient in the driver’s seat, but it does make them an important and valued member of the health-care team (as opposed to a passive player who is cared for or operated on). For some, this degree of patient involvement is unusual and infeasible given the lack of knowledge about health care, however, for the vast majority of cases, the patient is the initiator of care (e.g., ‘something is wrong and I have to see the doctor’). Also, for chronic illnesses and other health-care issues that require care over long periods of time or across multiple providers, the patient often becomes the one constant in the healthcare treatment equation. Movements toward patient self-care came to the forefront in areas such as mental health and care for people with disabilities, moving patients from institutional to community care and independent living. As lengths of stay have dropped, particularly in the United States after the adoption of prospective payments, additional care is provided in the patient’s own home (assisted by home health-care services), requiring increased patient self-care. In Europe and Japan, patient self-care is also being promoted in care for the elderly to avoid the prohibitive costs of institutionalized aged care.

Patient self-care promotes personal initiative and responsibility for one’s health, and helps patients make therapeutic choices that are more relevant to their own circumstances and preferences. This said, the ultimate goal of patient care is not just to improve the quality of life, but to increase the effectiveness of care. Existing patient self-management programs are often well monitored and supported by the health-care system, which needs to provide the necessary information, skills, and techniques for patients to be competent in the provision of their self-care. Traditional programs target consumers at risk of declining health or costly medical services through the application of evidence-based care, self-care support, multidisciplinary care coordination, and community collaboration. Self-care is a key to effectiveness and efficiency in the care of chronic disease, like diabetes, asthma, and mental diseases, which can be delivered directly by health-care providers, by specialized disease management organizations, or even by patients and patients’ groups.

Patients’ Role In Empowerment

As seen in Figure 4, the processes of empowerment are affected by both the patient and health-care system. Focusing first on the patient, a number of antecedents and barriers have been identified that support/limit patients’ involvement in the empowerment process. A number of patient outcomes of empowerment have also been identified in the literature.

Patient Antecedents

From the patient’s perspective, there are several antecedents to empowerment, including health literacy, knowledge and skills, and patient initiative and advocacy. Patients must have a degree of health literacy to be active participants in health-care delivery and decision making. Health literacy affects the ability of the patient to comprehend health-care providers and to understand the diagnosis, treatment, and expected outcomes. Patients also need a basic knowledge of health and health care, and the necessary cognitive skills and time to participate when necessary. The final key to patient empowerment is patient initiative: the ability and motivation to become involved in decision making or to marshal the necessary advocacy resources to precipitate change.

Patient Barriers

There are also several barriers that patients face in the road to empowerment, including ability to pay, physical and emotional limitations, and environment. Inability to pay for, or a lack of access to, health-care services is a key destabilizing force in the empowerment process. Patients may be further limited by their mental and health status and by the social environment in which they are situated. Addressing the barriers to empowerment at the individual level can be arguably more complicated, since these barriers concern attitudes and values, which are also often related to the social environment. For example, individuals have different attitudes regarding their willingness to participate in the medical decision-making process. One possible barrier to patient empowerment is that, a priori, patients might feel burdened by the process of decision making for the treatment of their health problems and may prefer to delegate all the decisions to their physician, although such decisions might not fit their needs, preferences, and values. Environment, or what is often referred to in the health systems literature as ‘place,’ also can act as a barrier to becoming empowered. For example, patients in rural or poor, inner-city areas may not only face access barriers to health care, but also have decreased access to education and advocacy groups. Access to both information and services is complicated, and hence often neglected, for people with disabilities.

Patient Outcomes

A range of outcomes of empowerment have been noted in the literature including improvements in health status, increased satisfaction, and self-efficacy. Empowerment has been studied in a number of clinical areas leading to a solid literature linking patient empowerment to better health outcomes, such as for chronic conditions, asthma, and diabetes. Empowerment leads to patient satisfaction given that an empowered patient will have more say in their health care and (more importantly) be aware of the complexities involved in determining the optimal treatment. Some longitudinal studies have also demonstrated the impact of education or self-management training on self-efficacy, which is among the most important outcomes of empowerment. Self-care in particular is an important way in which the patient, instead of the physician, takes control over his or her health, lifestyle changes, and care-seeking behavior, understanding when medical attention is necessary.

The Health-Care System And Patient Empowerment

It is unclear if, left to their own devices, the providers who run health systems would aim to promote or restrict patient empowerment. While all health-care systems strive for the good of their constituents, it has been recognized that paternalism has dominated the practice of medicine (i.e., physicians ‘care for’ patients rather than provide clients a service). While a number of health systems have attempted to promote consumer rights and patient-centered medicine, these are potentially a reaction to external pressures from patient groups calling for patients’ rights, as well as financial pressures from increased health-care consumerism, health tourism, and competition between providers. Again antecedents and barriers that support/limit the health-care system’s role in patient empowerment have been identified in the literature, as well as potential outcomes of patient empowerment on the health-care system.

Health System Antecedents

Regardless of how paternalistic or patient-centered health-care systems may set out to be, there are a number of antecedents that promote an atmosphere of patient empowerment within the health-care system: technology and innovation, competition, and clinician initiative and leadership. Arguably, technological change has done more to empower patients in the past 30 years than any other factor. Not only do we have new treatments, and even cures, for many diseases, but through innovation patients now need to spend less time in the hospital, have better access to information (especially through the Internet), and play an increased role in their own care. Competition drives innovation, whether it is promoted by way of professional, academic, or financial motives. By attempting to reach a larger customer base, physicians, hospitals, insurers, and industry have to provide products and services that patients deem beneficial. Finally, through the leadership of clinicians (especially nurses, social workers, and a limited number of physicians), health-care systems are changing to become more patient friendly. For example, the Institute of Medicine has been a major promoter of patient-centered care in the United States, and, at the micro and mesolevels, physicians, nurses, and other health-care professionals have, and will continue to play, an important role in the empowerment of patients. While patient-centered care is not new, some of the interest in patient-centered care, especially in the United States, can be seen as a backlash to the ‘financial-centered care’ approaches of managed care or reaction against health-care rationing in countries with national health systems with finite resources.

Health System Barriers

From a social justice perspective, health care is widely considered as a special good. Health care is also a complex good in that there is a great deal of uncertainty surrounding it. Limited resources for health care and substantial variations in care quality have led to government involvement in the financing and delivery of health care to ration and redistribute health care equitably. Rationing is often based on egalitarian principles, so that most people can afford health care as a means to function in society, or as a right. However, this perspective is often manifested as a form of paternalism instead of a respect for individual patient values and preferences. The historical development behind public provision, regulation, and financing of health care has often resulted in systems that impose barriers for patient empowerment in the health-care system such as inertia in work practices (especially in government bureaucracy), legal constraints, and financing by third-party payers.

Health care in any country is delivered (and in certain cases, financed) by a nexus of autonomous and semiautonomous agencies, spanning a range a professional and even cultural barriers, and thus pervaded by inertia. This is complicated by the traditional approach to medicine predominantly based on expert opinion and clinical judgment; thus care practices established over time have strongly influenced regulations, the role of professional societies, and governing agencies. Such an entrenchment of institutions/work practices – understood here as the customary ways, working rules, and legal regulations that shape and pattern behavior – in turn provides a context that explains the political and legal constraints to empowerment. For example, health reforms in many countries have encountered resistance to changes in medicine – a type of stickiness or path dependence – resulting in incremental reforms dominating the landscape of health policy making. Reliance on third-party payers or insurers can similarly inhibit empowerment as manifested by the development and spread of managed care financing approaches that insulate patients from decisions about health-care purchases. These three types of barriers may impede patient empowerment and perpetuate the current paternalist culture in medicine.

In the name of cost efficiency, choices are made on behalf of the patient. Choices available to the patient are purposely restricted both in terms of the range of providers available and the level of health care that can be consumed. The development of health technology assessment agencies aimed at promoting cost effectiveness, efficiency, and value of health care similarly have the potential to perpetuate medical paternalism and ignore the values of the patient through technically oriented evaluations and assessments, especially if they are restricted to the financial need of payers. In recognition, there is currently a movement to make these systems of evaluation more patient-centered, by explicitly assessing patient satisfaction with care and patients’ involvement in care, eliciting patient preferences about care and desired health outcomes to support shared and informed decision making, so that a dialogue is opened up between the health-care system and patients, expanding patient choice and patient involvement.

Health System Outcomes

The benefits of patient empowerment are not limited to the patient, but can affect health-care providers and the health-care system in positive ways, especially through increased respect for patients, increased adherence, and cost savings. As mentioned earlier, the active involvement of the patient has important consequences not just at the micro level (the patient’s own health) but at the macro level as well in terms of successful public health efforts to improve health and achieve cost savings from effective programs. A major outcome of patient empowerment in the health system will relate to how patients are viewed. If patients are perceived as co-equals with health-care providers, then they will be treated in a manner that respects their unique needs, individual priorities, and personal well-being. Recognizing the individuality of every patient may lead to greater support from patients in their treatment plan – a mutually agreed to regimen. This may represent an ideal model of care given the high prevalence of poor treatment adherence, limiting ability to achieve therapeutic goals as well as the efficient use of resources. Cost savings can be generated from a decrease in the duplication and misuse of services, a reduction in hospitalization rates in favor of outpatient services, and an increase in the use of efficacious and acceptable medical regimens.

Conclusions

While many of the processes supporting patient empowerment have been occurring through patient advocacy, facilitated though professional encouragement by some key clinicians, the path to widespread patient empowerment will require significant health system reforms. These system reforms need to institutionalize empowerment concepts, approaches, and processes, as well as to correct power imbalances in the system. Such reforms will need to challenge existing power structures, especially the dominance of the physician. Further, such reforms will challenge existing systems of health-care financing, particularly the paternalistic national, social solidarity systems that emerged over the twentieth century. Healthcare reforms will also be needed to transfer a greater degree of control to patients over their own health care. These include giving insured individuals greater choice in selecting treatments, level of premium payments, and user-fees. An example worth noting in this regard is Switzerland, which is regarded as a model of consumer-driven health care (CDHC). Switzerland reformed what was essentially a mosaic of 26 unique health-care systems into one healthcare system through the Health Insurance Law, which took effect in 1996. From voluntary coverage, the reform made compulsory the purchase of health insurance coverage by households and redefined solidarity in the context of calculated premiums and premium subsidies. From risk related premiums prior to 1996, premiums are community rated while subsidies of health insurance premiums are means-tested.

Another example can be found in the Netherlands, which replaced its system of compulsory health funds and private health-care insurance with a single statutory regime anchored in individual choice and responsibility beginning in 2006. Under the new system, every resident has the choice of insurer and policy, including a replacement scheme in the form of a health savings account for conscientious objectors (i.e., people who are opposed to insurance in principle). Like Switzerland, individuals in the Netherlands are free to choose the level of out-of-pocket costs that they are willing and/or able to bear.

In the United States, there has been considerable discussion in recent years about the potential empowering effects of consumer-directed health care (CDHC) – a type of health insurance that combines high deductibles (expenditures, set at some predetermined level, that a patient or family has to pay out of pocket before the insurer will contribute to costs) and, in certain situations, a savings account option. So, the majority of patients are essentially paying out of pocket, because most annual expenditures, barring any catastrophic events, do not exceed the deductible level. With regard to the savings option, similar to a health savings account (HSA), insurance providers offer incentives not to spend the money, including rollover and the ability to ‘cash in’ the savings. A limited number of other countries have explored consumer-directed, health financing options; Singapore is a notable example, as it is the first country to institutionalize HSAs. While there has been a great deal of rhetoric concerning the potential empowering nature of CDHC and HSAs, there is a lack of strong evidence as to the mechanism by which they do contribute, if any, to patient empowerment. In the United States, CDHC is often justified on the basis of cost savings (especially to the employer) and as a mechanism to cover uninsured persons who might not be able to afford the high cost of ‘first dollar’ (high deductible) health insurance. This said, these financing mechanisms have a great deal of potential to increase patient empowerment.

As health-care systems move in the right direction of involving patients as key stakeholders, there is hope that the patient will no longer be seen as a mere recipient of care. And, as health-care systems seek to become more responsive to the needs and preferences of patients, patients will become even more educated and involved in their own health care – in terms of better communication with their physician, being more selective of their insurer or provider, and being even more vocal in the health-care policy arena. The process of patient empowerment is changing the symbiotic roles of patients and providers in the health-care system, as is the responsiveness of the health-care system so as to create a partnership with the patient.

Bibliography:

- Anderson R, Funnel M, Fitzgerald J, and Marrero D (2000) The diabetes empowerment scale. Diabetes Care 23(6): 739–743.

- Chamberlin J (1997) A working definition of empowerment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 20(4): 43–46.

- Fallot RD and Harris M (2002) The Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model (TREM): Conceptual and practical issues in a group intervention for women. Community Mental Health Journal 38: 475–485.

- Gibson CH (1991) A concept analysis of empowerment. Journal of Advanced Nursing 16: 354–361.

- Gilbody S, Wilson P, and Watt I (2005) Benefits and harms of direct to consumer advertising: A systematic review. Quality and Safety in Health Care 14(4): 246–250.

- Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, and Tusler M (2004) Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Services Research 39: 1005–1026.

- Kanter RM (1993) Men and Women of the Corporation, 2nd edn. New York: Basic Books.

- Kim SC, Boren D, and Solem SL (2001) The Kim Alliance Scale. Development and preliminary testing. Clinical Nursing Research 10(3): 314–331.

- Linhorst DM, Hamilton G, Young E, and Eckert A (2002) Opportunities and barriers to empowering people with severe mental illness through participation in treatment planning. Social Work 47(4): 425–434.

- Loukanova S, Molnar R, and Bridges J (2007) Promoting patient empowerment in the health care system: Highlighting the need for patient-centered drug policy. Expert Review of PharmacoEconomics and Outcomes Research 7(3): 281–289.

- Loukanova S and Bridges J (2008) Empowerment in medicine: An analysis of publication trends 1980–2005. Central European Journal of Medicine 3(1): 105–110.

- Man DW, Lam CS, and Bard CC (2003) Development and application of the Family Empowerment questionnaire in brain injury. Brain Injury 17(5): 437–450.

- Menon ST (2002) Toward a model of psychological health empowerment: Implications for health care in multicultural communities. Nurse Education Today 22: 28–39.

- O’Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, et al. (1999) Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: A Cochrane systematic review. British Medical Journal 319: 731–734.

- Pignone M, DeWalt DA, Sheridan S, Berkman N, and Lohr KN (2005) Interventions to improve health outcomes for patients with low literacy. A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine 20(2): 185–192.

- Rappaport J (1984) Studies in empowerment: Introduction to the issue. Prevention in Human Services 3: 1–7.

- Rappaport J (1987) Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology 15: 121–148.

- Rogers ES, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML, and Crean T (1997) A consumerconstructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services 48: 1042–1047.

- Zimmerman MA (1990) Taking aim on empowerment research: On the distinction between individual and psychological conceptions. American Journal of Community Psychology 18(1): 169–177.

- Zimmerman MA (1995) Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology 23(5): 581–599.

- Acquadro C, Berzon R, Dubois D, et al., PRO Group(2003) Incorporating the patient’s perspective into drug development and communication: An ad hoc task force report of the patient-reported outcomes (PRO) harmonization group meeting at the Food and Drug Administration, February 16, 2001. Value in Health 6(5): 522–531.

- Anderson RM and Funnel MM (2005) Patient empowerment: reflections on the challenge of fostering the adoption of a new paradigm. Patient Education and Counseling 57: 153–157.

- Arnstein SRA (1969) Ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35(4): 216–224.

- Bastian H (1998) Speaking up for ourselves. The evolution of consumer advocacy in health care. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 14(1): 3–23.

- Bridges J (2003) Stated preference methods in health care evaluation: An emerging methodological paradigm in health economics. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 2(4): 213–214.

- Bridges J and Jones C (2007) Patient based health technology assessment: A vision of what might one day be possible. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 23(1): 30–35.

- Gagnon M, Hibert R, Dube M, and Dubois MF (2006) Development and validation of an instrument measuring individual empowerment in relation to personal health care: The Health Care Empowerment Questionnaire (HCEQ). American Journal of Health Promotion 20(6): 429–435.

- Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, and Greene SM (2005) Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Medical Care 43(5): 436–444.

- Tomes N (2006) The patient as a policy factor: A historical case study of the involvement of the consumer/survivor movement in mental health. Health Affairs (Millwood) 25(1): 720–729.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.