This sample Population Growth Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Dynamics Of Population Growth

In the last half-century, population growth has proceeded at a rate unprecedented in the history of the planet. The human population took hundreds of thousands of years to grow to 2.5 billion people in 1950. Then, within the time span of just 50 years, the world’s population more than doubled to exceed six billion people. Most of this growth has occurred in developing countries where advances in public health have contributed to lower mortality at all ages. Until recently, death rates fell faster than birthrates, resulting in rapid population growth.

While growth rates have fallen from their all-time high, human numbers are still increasing. The world population is growing by about 1.2% a year, down from a peak of roughly 2% in the late 1960s. However, even at this lower growth rate, the world’s population still experiences a net increase of about 76 million people each year; many more than the 50 million or so added annually in the 1950s when the term population explosion first gained currency.

Population Projections

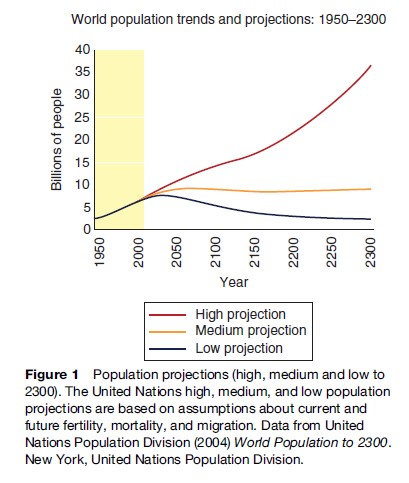

World population could reach anywhere between 7.7 billion and 10.6 billion by the mid-21st century, based on the 2004 United Nations (UN) projections, depending mostly on future birthrates (UN, 2007). A population projection is a conditional forecast based on assumptions about current and future fertility, mortality, and migration. Figure 1 shows the UN’s high, medium, and low projections for2300. The variances between these three projections stem from differences in projected fertility; that is, the average number of children a woman has in the study population. In the high projection, global fertility averages around 2.6 children per woman. In the medium, it averages about 2.1 children per woman. The lowest fertility projection assumes an average of about 1.6 children per woman. Most users of these projections tend to cite the medium projection as the most likely. It is important, however, to be aware of the low and high projections as a kind of outer bounds of demographic possibility.

Recent UN projections are lower than most previous projections for the same period, reflecting earlier-than expected declines in family size in some countries. Yet even under the UN’s slow-growth scenario, the population would continue to grow for at least four more decades, to about 7.8 billion people, before declining gradually. Under the UN’s high-growth scenario, the world population would exceed 35 billion late in the 23rd century and continue growing rapidly. The long-term medium projection suggests that the population would peak just above 9.1 billion around 2075, then drift downward to around 8.5 billion before growing again late in the 23rd century.

However, there is no certainty in projecting future population trends. All population projections are based on fairly rigid assumptions and therefore cannot provide completely reliable guides to the world’s demographic future.

The Demographic Transition

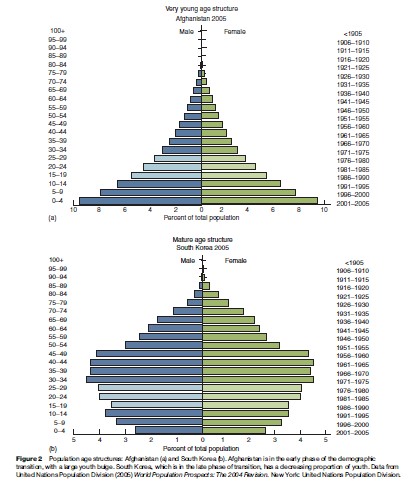

The transformation of a population that is characterized by high birth and death rates to one in which people tend to live longer lives and raise smaller families is called the demographic transition. This transition typically shifts population age structure from one dominated by children and young adults up to age 29 to one dominated by middle-aged and older adults age 40 and above. About one-third of the world’s countries, including most of Europe, Russia, Japan, and the United States, have effectively completed this transition. These 65 or so countries contain half of the world’s population.

In Figure 2(a) and 2(b), two population pyramids geometrically display age structures: The proportion of people per age group, relative to the population as a whole. Afghanistan is an example of a country in the early phase of the demographic transition. Such countries typically have age structures composed predominantly of young adults and children (commonly called a youth bulge). As countries advance into the late phase of transition, as shown by the population age structure of South Korea, the proportion of children begins to decrease, but a youth bulge persists for a decade or two, moving upward into the older age cohorts.

Fertility Rates

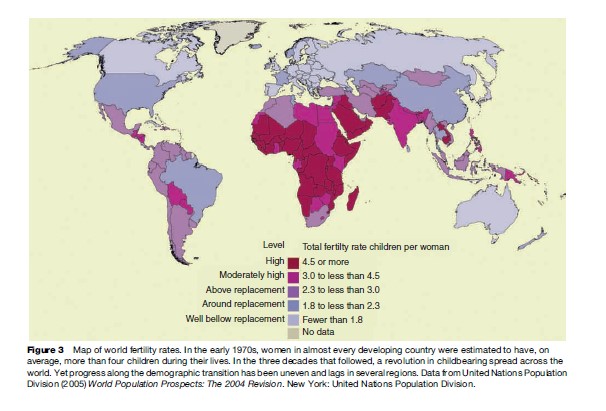

Improvements in the education of girls and the overall status of women, together with increased access to contraceptive methods, have played important roles in advancing the demographic transition and reducing the global average fertility rate from 4.9 children in the first half of the 1960s. Nevertheless, the world’s average fertility rate is currently 2.7 children, considerably higher than the level of fertility that would ultimately stabilize the growth of most populations (UN, 2005). This level, called replacement fertility, represents the number of children a couple needs to have in order to replace themselves in the population. The values for replacement fertility are surprisingly diverse and vary by country, reflecting mostly differential rates of survival of children to their own reproductive ages. Replacement fertility rates range today from a low of 2.04 for Re´union Island to a high of 3.35 in Swaziland (Engelman and Reahy, 2006).

In nearly all developing countries, the average number of childbirths per woman has decreased in recent decades. While a number of factors have contributed to this revolution in childbearing, improved access to modern contraceptive methods has played a key role, in most of sub-Saharan Africa, in many countries of the Middle East, and in parts of South Asia. Growing at rates of 2.5–3.5% annually, these countries could double in size in 20 to 30 years. Almost all industrialized countries now have an average family size of fewer than two children and are growing relatively slowly, or even declining in population. In some eastern and southern European countries, women have an average of 1.2 or 1.3 children. These nations comprise less than 5% of the world’s population, however, and thus have little influence on overall global trends (Figure 3).

Population Aging

Due to low fertility rates in some developed countries, concerns are emerging about population aging and the possibility of population decline. Population aging is defined as a rising average age within a population and is an inevitable result of longer life expectancies and lower birthrates. In many societies, population aging is a positive social and environmental development, but its potential persistence to extreme average ages is worrisome to governments concerned with the funding of social security programs and general economic growth. However, like population growth itself, population aging cannot continue indefinitely and will eventually end, even in stabilized populations.

Population decline is occurring in some industrialized countries. European population growth, which fueled immigration to the Americas for three centuries, has ended and begun to reverse course, despite significant streams of migration from developing countries. If low fertility rates persist, the populations of Germany, Italy, Russia, and Spain could shrink by 5–10% by 2025-an average reduction of 0.5% per year. In East Asia, the populations of Japan, China, and South Korea are likely to peak and begin a gradual decline in size before the middle of the 21st century. However, major declines outside Europe and East Asia are unlikely for decades.

Factors That Influence Population Growth

Contraceptive Prevalence

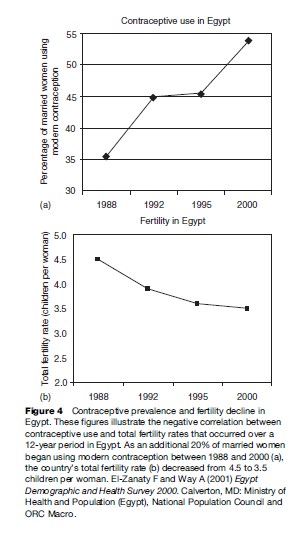

Demographers attribute much of the recent decline in global fertility to improved access to and use of family planning information and methods. More than half of all married women in developing countries now use family planning, compared to 10% in the 1960s. Across the developing world, use of modern methods of contraception ranges from less than 8% of married women in Western and Central Africa to 65% in South America. The highest contraceptive prevalence rate in the world is in Northern Europe, where 75% of married women are currently using a modern method of family planning (Figure 4) (UN, 2004).

Despite these gains in availability, contraceptive services are still difficult to obtain, unaffordable, or of poor quality in many countries. Approximately 201 million married women worldwide who would prefer to delay or avoid having another child are not using modern methods of contraception (Alan Guttmaches Institute and UNFPA, 2003). Unmet need is highest in sub-Saharan Africa, where 46% of women at risk of unintended pregnancy are not using any contraceptive, presumably reflecting lack of access or other barriers. Meanwhile, in developing countries, the number of women in their childbearing years is increasing by about 22 million women a year. For fertility rates to continue their global decline, family planning services will have to expand rapidly to keep up with both population growth and rising demand.

Mortality From HIV/AIDS And Other Infectious Diseases

Like no other disease, AIDS debilitates and kills people in their most productive years. Ninety percent of HIV-associated fatalities occur among people of working age, who leave behind large numbers of orphans – currently 11 million in sub-Saharan Africa alone – with few means of supporting themselves. A projected 10–18% of the working-age population will be lost in the next 5 years in nine central and southern African countries, primarily due to AIDS-related illnesses (Cincotta et al., 2003).

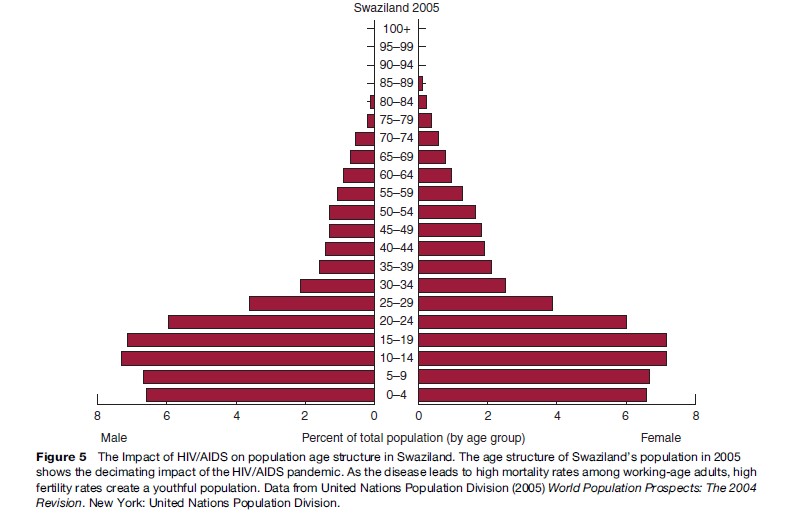

High rates of AIDS mortality lead to a bottle-shaped population age structure, with very high proportions of young people and many fewer older adults. As birth rates remain high while people of reproductive age die from AIDS-related causes, the share of young dependants to each working-age adult rises dramatically. Without significant advances in HIV prevention or in access to life-saving drugs in poor countries, AIDS-related mortality rates could increase significantly. UN population projections suggest that some countries will experience lower population growth rates from AIDS, but high fertility rates mean that population size in these countries is likely to still increase significantly (Figure 5).

Population growth also threatens global health through increased vulnerability to other infectious diseases. A growing population size living in and moving to and from densely populated areas creates expanded opportunities for disease to spread and intensify. At the country and community levels, governments often lack the resources to improve sanitation and public health services at the same rate that populations are increasing. At the household level, evidence from demographic surveys suggests that children born after several siblings tend to receive fewer immunizations and less medical attention than children born earlier or in smaller families (Rutstein, 2005). The cumulative effect of all these influences is a greater risk of disease with higher birthrates and rapid population growth.

Gender Equity

When women are able to determine the size of their families, fertility rates are generally lower than in settings where women’s status is poor. In particular, there is a strong correlation between female school enrollment rates and fertility trends. In most countries, girls who are educated, especially those who attend secondary school, are more likely to delay marriage and childbearing. Women with some secondary education commonly have between two and four fewer children than those who have never been to school (Conly, 1998).

Early childbearing often limits educational and employment opportunities for women. When women have an education, their children tend to be healthier; in India, a baby born to a woman who has attended primary school is twice as likely to survive as one born to a mother with no education. By delaying marriage and childbearing, educating girls also helps lengthen the span between generations and slow the momentum driving future population growth.

Migration

The movement of people from one country to another – emigration in the case of those who leave their native country and immigration to describe the increase in a country’s foreign-born population – continues to increase in both scale and frequency. International migration has doubled in the past 25 years, with about 200 million people – 3% of the world’s population – today living in a country different from the one in which they were born. Approximately 60% of international migrants have chosen to live in developed countries, but migration within developing countries remains significant. Asia has three times as many international migrants as any other region of the developing world.

Although there are many reasons for increases in migration, the dramatic population growth of the past few decades has been a primary impetus. This has led, with a 15to 20-year time lag, to the rapid growth of the world’s labor force, especially among the young adults who make up the age group most likely to migrate. Tens of millions of people are added to the labor force each year, and the search for decent jobs is the leading reason people migrate. In addition deteriorating environmental conditions related to population growth – water and food shortages, for example, or human-induced climate change – can also spur large movements of population across international borders. Lower rates of population growth can help ease the pressures to migrate and improve the underlying conditions that force many people to seek a better life elsewhere.

Government Policies

Throughout history, government regulations on fertility – either by promoting or restricting childbirth – have directly affected population dynamics. Authoritarian regimes have pursued pro-natalist policies to increase the size of a population for militaristic, nationalist, and/or economic reasons. A few countries, including the world’s most populous – China and India – have placed direct and indirect regulations on their citizens’ fertility as a means of reducing population growth.

All state regulation of fertility, whether pro-natalist or intended to slow population growth, has been strongly criticized by human rights advocates. The importance of individual freedom of choice concerning fertility and reproductive health was outlined and agreed upon by 19 countries in 1994 at the International Conference on Population and Development.

Worldwide, more than one-fifth of all pregnancies are terminated annually. The prevalence of abortion is one indication of the high level of unintended pregnancy worldwide. Political disagreements over the highly contentious issue of abortion have in recent years hampered the funding of population and reproductive health programs in both the United States and in many developing countries.

As in the case of abortion, government policy related to international migration cannot really be called population policy, since in no cases is it expressly designed to remedy perceived deficiencies in national population trends. Nonetheless, government policies on migration and the process itself do influence the pace and distribution of population change, and it remains possible that some countries with especially low fertility may design future migration policies specifically to slow either the aging or the decline of their populations, or both.

Impacts Of Population Growth

Health

High fertility rates can have an adverse effect on the health of women and children, especially in developing countries that lack a health infrastructure. Every year, an estimated 529 000 women die in pregnancy or childbirth (WHO, 2004), and for every woman who dies as many as 30 others suffer chronic illness or disability (Ashford 2002). Moreover, every year more than 46 million women resort to an induced abortion; 18 million do so in unsafe circumstances. Each year, approximately 68 000 women die from unsafe abortions and tens of thousands more suffer serious complications leading to chronic infection, pain and infertility (WHO, 2005).

Pregnancy-related deaths overall account for one quarter to one-half of deaths to women of childbearing age. For both physiological and social reasons, pregnancy is the leading cause of death for young women aged 15–19 worldwide, with complications of childbirth and unsafe abortion being the major factors (WHO, 2004). Furthermore, each year 3.3 million babies are stillborn, more than 4 million die within 28 days of birth, and another 6.6 million children die before age 5 (UN, 2005).

The timing of births has an impact on child health. When a pregnant woman has not had time to fully recover from a previous birth, the new baby is often born underweight or premature, develops too slowly, and has an increased risk of dying in infancy or contracting infectious diseases during childhood (Rustein, 2005). Research shows that children born less than 2 years after the previous birth are about 2.5 times as likely to die before age 5 than children who are born 3–5 years apart (Setty-Venugopal and Upadhyay, 2002).

Chronic hunger, which affects an estimated 852 million undernourished people worldwide, is another critical health issue that is directly linked to population growth. The number of chronically hungry people in developing countries increased by nearly 4 million per year in the latter part of the 1990s. Globally, the number of food emergencies each year has doubled over the past two decades, totaling more than 30 per year. Africa has the highest number and proportion of countries facing food emergencies. The average number of food emergencies in Africa has almost tripled since the 1980s, and one-third of the population of sub-Saharan Africa is undernourished. A 1996 study by the Food and Agriculture Organization estimated that Africa’s food supply would need to quadruple by 2050 just to meet people’s basic caloric needs under even the lowest, and most optimistic, population growth projections (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2004).

Poverty

Improving reproductive health care, including family planning, can have economic benefits. The expanded provision of family planning services was responsible for as much as a 43% reduction in fertility between 1965 and 1990 in developing countries; falling fertility rates, in turn, have been associated with an average 8% decrease in the incidence of poverty in low-income countries. Countries with poverty rates above 10% have fertility rates that are double those in richer countries (Leete and Schoch, 2003).

Lowering fertility rates through access to family planning information and contraceptive supplies has both macro and microeconomic benefits. Just as national governments are able to spend more per capita on social welfare when population growth slows, parents can invest more in health and education costs for each child if they have fewer children. Couples who have smaller families are often able to have women work outside the home and to save more of their income, thus increasing the national labor supply, investment, and growth.

Economists credit declining fertility over the past four decades as one contributor to sustained economic growth among the East Asian Tiger countries, which include South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Hong Kong. Research indicates that shifts to smaller family size and slower rates of population growth in the region helped create an educated workforce, expand the pool of household and government savings, raise wages, and dramatically increase investments in manufacturing technology (Williamson and Higgins, 1997; Williamson, 2001). A shift to smaller families produced three important demographic changes:

Slower growth in the number of school-age children, a lower ratio of dependants to working-age adults (dependency ratio), and a reduced rate of labor force growth. As fertility declined, household and government investments per child increased sharply, as did household savings, while governments reduced public expenditures. Domestic savings rose to displace foreign funds as the leading source of private sector investment and countries that had been major foreign aid recipients emerged to become a significant part of industrialized countries’ export market. Although this model of fertility decline and economic growth has not yet been replicated in other regions of the world, the East Asian experience demonstrates how important a smaller average family size can be to economic development.

Natural Resources

Greater numbers of people and higher per capita resource consumption worldwide are multiplying humanity’s impacts on the environment and natural resources. While population is hardly the only force applying pressure to the environment, the challenges of sustainability and conservation become harder to address as the number of people continues to increase. Currently, more than 1.3 billion people live in areas that conservationists consider the richest in nonhuman species and the most threatened by human activities. While these areas comprise about 12% of the planet’s land surface, they hold nearly 20% of its human population. The population in these biodiversity hotspots is growing at a collective rate of 1.8% annually, compared to the world population’s annual growth rate of 1.3% (Engelman, 2004). Human pressure on renewable freshwater, cropland, forests, fisheries, and the atmosphere is unprecedented and continually increasing.

Changes in ecosystems (natural systems of living things interacting with the nonliving environment) can greatly impact human prosperity, security, and public health. Food supply, fresh water, clean air, and a stable climate all depend upon healthy ecosystems. Human-induced or human-accelerated disturbances to ecosystems can increase the risk of acquiring infectious diseases, either directly or through the impact made to biodiversity. For example, air and water pollution are linked to increases in asthma and other respiratory problems, as well as cancer and heart disease. The emergence of Lyme disease in the United States is thought to be associated with habitat loss and diminished biodiversity. Many experts believe that climate change is also contributing to a rise of infectious disease worldwide, as warmer temperatures bring pathogens to new geographical areas (Epstein et al., 2003).

Currently, more than 745 million people face water stress or scarcity (Engelman, 2004). Much of the fresh water now used in water-scarce regions originates from aquifers that are not being refreshed by the natural water cycle. In most of the countries where water shortage is severe and worsening, high rates of population growth exacerbate the declining availability of renewable fresh water. Cultivated land is at similar levels of critical scarcity in many countries. Despite the Green Revolution and other technological advances, agriculture experts continue to debate how long crop yields will keep up with population growth. The food that feeds future generations will be grown mostly on today’s cropland, which must remain fertile to keep food production secure. Easing world hunger would be even more difficult if population growth resembles demographers’ higher projections.

Likewise, future declines in the per capita availability of forests, especially in developing countries, are likely to pose major challenges for both conservation and for the provision of food, fuel, and shelter necessary for human well-being. Based on the United Nations’ medium population projection and current deforestation trends, by 2025 the number of people living in forest-scarce countries could swell to 3.2 billion in 54 countries (Engelman, 2004). Most of the world’s original forests have been lost to the expansion of human activities.

In 2002, per capita emissions of CO2 continued a 3year upward climb that appeared unaffected by the global economic jolt from the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States. In the 1999–2002 period, population growth and increasing per capita fossil-fuel consumption joined forces on an equal basis to boost global CO2 emissions rapidly. With about 4.7% of the world’s population, the United States accounted for almost 23% of all emissions from fossil-fuel combustion and cement manufacture, by far the largest CO2 contributor among nations. (China, with more than four times the U.S. population, is number two.) Emissions remained grossly inequitable, with one-fifth of the world’s population accounting for 62% of all emissions in 2002, while another — and much poorer — fifth accounted for 2%. Population growth and the corresponding increase in global CO2 emissions are of crucial importance to scientists and policy makers concerned with the potential effects of global climate change.

Conflict And Security

During the last three decades of the twentieth century, the demographic transition was correlated with continuous declines in the vulnerability of countries to civil conflicts, including ethnic wars, insurgencies, and terrorism. Progress through the demographic transition gives countries a more mature and less volatile age structure, slower workforce growth, and a more slowly growing school-age population. It reduces urban growth and gives countries additional time to expand infrastructure, meet the demand for public services, and conserve dwindling natural resources. Countries in the early and middle phases of demographic transition have cumulatively been significantly more vulnerable to civil conflict than late-transition countries.

The likelihood of civil conflict steadily decreased for high-risk countries as they experienced overall declines in birth and death rates. From the 1970s to the 1990s, a decline in a country’s annual birth rate of ten births per 1000 people corresponded to a decrease of approximately 10% in the likelihood of an outbreak of civil conflict.

The demographic factors most closely associated with the likelihood of a new outbreak of civil conflict during the 1990s were a high proportion of young adults ages 15–29 years and a rapid rate of urban population growth. When coupled with a large youth bulge, countries with a very low availability of cropland and/or renewable fresh water, plus a rapid rate of urban population growth, had a roughly 40% probability of experiencing an outbreak of civil conflict in the 1990s. Migration and differential rates of population growth among ethnic groups competing for political and economic power have also played important roles in political destabilization.

Over the past 40 years, the demographic transition has been progressing impressively in nearly all of the world’s regions. Most of the world’s countries are moving toward a distinctive range of population structures that make civil conflict less likely. Yet this progress through the demographic transition is not universal. Continuing declines in birth rates and increases in life expectancy in the poorest and worst-governed countries will be required.

Conclusion

In summary, the world is demographically complex, diverse, and divided in ways that have no precedent in human history. No one can say with confidence how problematic this diversity is or how humanity’s demographic future will unfold. However, it is certain that given the linkages between world population growth and disease and mortality, environmental resources, gender equity, and civil conflict, demography will play a major role in the future of global public health.

Bibliography:

- The Alan Guttmacher Institute (1999) Induced Abortion Worldwide. New York: The Alan Guttmacher Institute.

- The Alan Guttmacher Institute and UNFPA (2003) Adding it up: The Benefits of Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health Care. New York: AGI and UNFPA.

- Ashford L (2002) Hidden Suffering: Disabilities from Pregnancy and Childbirth in Less Developed Countries. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

- Conly S (1998) Educating Girls: Gender Gaps and Gains. Washington, DC: Population Action International.

- El-Zanaty F and Way A (2001) Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 2000. Calverton, MD: Ministry of Health and Population (Egypt), National Population Council and ORC Macro.

- Engelman R (with Anastasion D) (2004) Methodology. People in the Balance: Update 2004. http://www.populationaction.org/ resources/publications/peopleinthebalance/downloads/ AcknowlAndMethodo.pdf.

- Engelman R and Leahy E (2006) How Many Children Does It Take to Replace Their Parents? Variation in Replacement Fertility as an Indicator of Child Survival and Gender Status. Paper presented at the Population Association of America annual conference Los Angeles, 30 March–1 April.

- Epstein PR, Chivian E, and Frith K (2003) Emerging diseases threaten conservation. Environmental Health Perspectives. 111(10): A506–A507.

- Food Agriculture Organization (2004) The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2004. Rome: FAO.

- Global Commission on International Migration (2005) Migration in an Interconnected World: New Directions for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: GCIM.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (2005) AIDS Epidemic Update: December 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- Leete R and Schoch M (2003) Population and poverty: Satisfying unmet need as the route to sustainable development. Population and Poverty: Achieving Equity, Equality and Sustainability 8: 9–38.

- Rutstein S (2005) Effects of preceding birth intervals on neonatal, infant and under-five years mortality and nutritional status in developing countries: Evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 89 (supplement 1): s7–s24.

- Setty-Venugopal V and Upadhyay UD (2002) Three to Five Saves Lives. Population Reports. L13: 2. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University. UNFPA.

- State of World Population (2004) Reproductive Health and Family Planning. http://www.infpa.org/swp/2004/english/ch6/page3.html (accessed February 2006).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (2005) State of the World’s Children 2005. New York: UNICEF.

- United Nations Population Division (2004) World Population to 2300. New York, United Nations Population Division.

- United Nations Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2004) World Contraceptive Use 2003. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division (2005) Word Population Prospects: The 2004 Revision. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations Population Division (2005) World Population Prospects: The 2004 Revision. New York: United Nations Population Division.

- United Nations Population Division (2007) World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision. New York: United Nations Population Division.

- Williamson JG and Higgins M (1997) The accumulation and demography connection in East Asia. Proceedings of the Conference on Population and the East Asian Miracle. Honolulu, Hawaii: East-West Center.

- Williamson JG (2001) Demographic change, growth, and inequality. In: Birdsall N, Kelley AC, and Sinding SW (eds.) Population Matters: Demographic Change, Economic Growth, and Poverty in the Developing World, pp. 107–136. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

- World Health Organization (2004) Maternal Mortality in 2000: Estimates Developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- World Health Organization (2005) The World Health Report 2005: Make Every Mother and Child Count. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Ashford L (1995) New Perspectives on Population: Lessons from Cairo. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

- Birdsall N, Kelley A, and Sinding S (eds.) (2001) Population Matters: Demographic Change, Economic Growth, and Poverty in the Developing World. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bongaarts J (1994) Population policy options in the developing world. Science 263: 771–776.

- Chivian E (ed.) (2002) Biodiversity: Its Importance to Human Health: Interim Executive Summary. Cambridge, MA: Center for Health and the Global Environment Harvard Medical School.

- Cincotta R, Wisnewski J, and Engelman R (2000) Human population in the biodiversity hotspots. Nature 404: 990–992.

- Coale A and Hoover E (1958) Population Growth and Economic Development in Low-Income Countries. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Cohen JE (1995) How Many People Can the Earth Support? New York: Norton.

- Engelman R and LeRoy P (1993) Sustaining Water: Population and the Future of Renewable Water Supplies. Washington, DC: Population Action International.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (1996) Food Requirements and Population Growth. World Summit Background Document No. 4. Rome: FAO.

- Livi-Bacci M (1992) Concise History of World Population. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Lutz W, O’Neill B, and Scherbov S (2003) Europe’s population at a turning point. Science 299: 1991–1992.

- Mason A (ed.) (2002) Population Change and Economic Development in East Asia: Challenges Met, Opportunities Seized. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- National Research Council (1986) Population Growth and Economic Development: Policy Questions. Washington, DC: National Academy of Science Press.

- Robey B, Rutstein S, and Morris L (1993) The fertility decline in developing countries. Scientific American 269: 60–67.

- Smil V (1991) Population growth and nitrogen: An exploration of a critical existential link. Population and Development Review 17: 569–601.

- United Nations (1994) Programme of Action Adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development. New York: United Nations.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.