This sample Role of the Private Sector in Health Care Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Private clinics and hospitals and privately employed individuals provide a significant volume of health services in almost every country in the world. The extent of provision and the areas of involvement vary across countries; however, variations in the size of the private health sector cannot be systematically linked to the equity, quality, coverage, or other measures of health system performance, nor to the achievement of health policy goals. Despite this, private engagement in health provision remains a highly emotive topic. The reason for this derives in part from a widespread misunderstanding of private healthcare delivery and the role it plays in health systems. This research paper will clarify the key definitions related to private service provision and summarize current knowledge on the role that the private sector plays in both high and low-income countries. It will also present some of the most important issues that arise in discussions of private provision from public health and policy perspectives.

A source of confusion for students of public health is the often-complex overlap between financing and delivery of health services. The common perception is that public payment for health services necessarily implies public provision of health services. This is not the case, and misunderstanding of this basic point leads to highly erroneous conclusions about the health delivery systems of both low-income and high-income countries. This research paper focuses on private service delivery.

Private service providers are heterogeneous, encompassing world-class hospitals, unqualified drug sellers, and the whole range of providers in between. The role of the private sector varies by level of care, playing a limited role in in-patient care in most countries, and carrying more importance in the distribution and sale of pharmaceuticals, outpatient care, and informal care in low-income countries.

Background

Historically, health-care services were private in all countries until the rise of centralized governments in Europe and Asia in the eighteenth century. Governments’ first interventions in health arose primarily to organize epidemic prevention and public health services, including mandatory hospitalization for tuberculosis, plague, leprosy, and other infectious diseases. With the rise of immunization options in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, publicly supported health care expanded to prevention in many countries. Throughout this period, care and treatment of noninfectious diseases remained largely private, either for-profit or provided through religious charities. Government financing of care and treatment developed in parallel to the growth in government-supported education, and by the second half of the twentieth century, government sponsored medical care had come to be seen as a central pillar of national social services.

Even where government financing of care is the strongest, in Western Europe and other high-income countries, service provision still often remains in the hands of private hospitals, clinics, and clinicians. Historical development and the institutional structure of the state appear more important in setting the public–private mix of care provision than national values. The social insurance systems of continental Europe, for example, based on the corporatist model of government, have established systems with extensive private provision, while ensuring equity of access through their funding arrangements (Saltman et al., 2004).

The Private Sector Today

It is necessary to look at three elements of service delivery to understand private provision of health-care services and how it is distinct from public provision: (1) the activity of providing services; (2) the facility in which provision takes place; and (3) the employment arrangements for individuals providing services.

Each of these may be private or public, and without distinguishing among them, it is difficult and sometimes meaningless to refer to service provision as public or private.

The organization of the activity or operation of providing health care can be public or private, with the distinction determined by the control of decisions about the activity, and control of funds generated by the activity. When clinics or hospitals are publicly owned, key managerial decisions (e.g., about hiring practices or services to be offered) are determined by government rules. Leftover funds generated by their operation belong to the treasury or public purse. When clinics or hospitals are privately owned, the organization itself determines the key decisions about its operation. The organization (or its owners) has a legal claim to leftover revenue.

This makes the possession of the rights to leftover income and the responsibility for debts the clearest factors for determining to which category the organization belongs.

Much of primary health care, for example, is delivered by physicians who run their practice as a small business. They control the key decisions about how to run the practice. They are responsible for any debts, and are entitled to any profits.

The facility or premises within which services are being provided may be public or private. Public clinics are almost always located in publicly owned buildings. Private clinics and hospitals often do not own but rather rent their premises. Sometimes private clinics are located in publicly owned buildings. This does not make the business, or operation, any less ‘private,’ since they still decide how to run their practice, and leftover revenue remains with the organization or its owners.

The employment arrangements for health professionals can be either public or private. Most staff working within private health-care organizations are in private employment contracts. Most staff working in public facilities are on public employment contracts. These categories are not airtight, however. In a number of African countries, health ministries provide publicly employed health workers as a form of support to mission (nonprofit) hospitals. Public hospitals in high-income countries often have staff working under private employment contracts for the provision of specialized services. Hence, even once the public or private nature of a health-care organization has been determined, an examination of the employment arrangements within the organization may reveal a more complex picture. Public and private employment arrangements have different implications for incentives and hence the behavior of individuals working in health-care organizations.

Nonprofit Versus For-Profit

Another important distinction among private health-care activities is their organizational form, including their profit orientation. This distinction is important because it influences the behavior of the organizations and, in particular, may influence the degree to which behavior is likely to be more social versus opportunistic. There is also some evidence that they differ systematically with respect to efficiency and productivity, with for-profits exhibiting higher levels in some studies.

Many private health-care activities are organized as nonprofit entities. They can be distinguished from other service providers by the ‘nondistribution constraint’ – that is, even though they may generate a ‘surplus’ of revenue over expenditures, they cannot distribute this surplus to individuals in the form of profits. They can spend it in other ways, including higher wages or ‘perks’ to their employees and managers, training/education, research, community service, and subsidizing less profitable services. Nonprofit organizations are also distinct from forprofits in that they often pursue objectives other than the financial bottom line. It is important to keep in mind that only a small portion of nonprofit organizations are socially oriented. Many membership organizations (e.g., cooperatives of milk producers) or lobbying organizations (e.g., the National Rifle Association) are organized as nonprofits, but are pursuing the interests of their members and/or contributors rather than society at large.

For-profit organizations can be organized as either small businesses or investor-owned (Deber, 2002). The majority of private health-care providers are organized as small businesses (sometime referred to as ‘proprietary’). Most private clinics and diagnostic labs, for example, are organized this way. While these organizations are run as a business, and the proprietor certainly takes home any profits generated, they do not have to generate a return on any investment by external shareholders. This difference is perceived to reduce the focus on the financial bottom line, allowing professional values and ethics to exert a greater influence. Hence, typically, policy makers are less concerned with quality skimping and patient ‘cream skimming’ in the case of small health-care businesses.

Hospitals require very large amounts of capital investment, and therefore private hospitals are usually investor-owned. External investors are understood to prioritize return on investment – in either the form of distributed profits or appreciation of the value of the hospital. The focus on the hospital as a business often leads to concern by policy makers and regulators that profit maximization may reduce health-care quality or that unprofitable patients will be discouraged or turned away.

Private Health-Care Provision In High-Income Countries

In both high and low-income countries, there is extensive private provision of health-care services. However, private providers play different roles and operate differently in the two groups of countries (Saltman et al., 2006). This section will characterize private provision in high-income countries. The next section will discuss low-income countries.

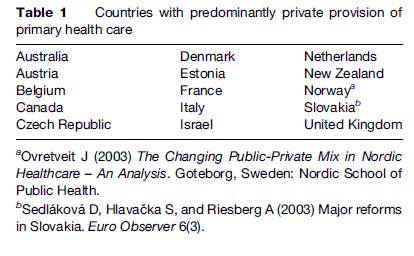

Primary health care is extensively delivered by physicians organized as small businesses in high-income countries, with the exception of Sweden, Norway, and Finland (see Table 1). In most of these countries, private providers play a coordinated role in the national health system, reflected in the public (or social) funding of the services. Funding is usually linked to the delivery of a specific package of services – both curative and preventive (e.g., immunizations, well-baby checkups). Hence, in the countries with predominantly private primary care systems, part of the package of core public health services is delivered by private providers. However, in a few cases, public funding is limited to public providers. As a result, patients who utilize private services must pay themselves (e.g., Spain, Portugal).

In high-income countries, a large portion of hospital service is provided by nonprofit organizations, many of which emerged from religious charities. Virtually the entire hospital sectors of Canada and the Netherlands are organized as a statutory class of nonprofit hospitals. The majority of hospitals in Belgium (99 of a total of 157) are nonprofit, as are 30% of hospitals in France. In Germany, 37% of hospital beds are nonprofit. The nonprofit hospital sector is important in Australia and the United States as well. For-profit (investor-owned) hospitals are less common, playing a substantial role in delivery in only Australia, the United States, Germany, and France.

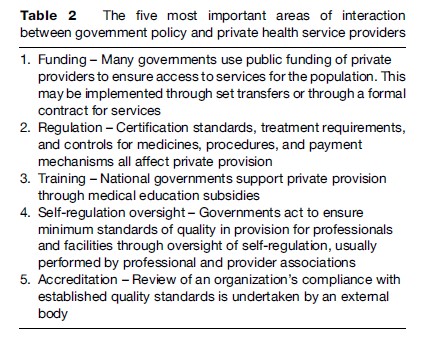

This private provision takes place within a framework of extensive public or social funding, as well as extensive regulation and self-regulation, including accreditation (see Table 2). The result is that private provision is well-integrated into the system and performs relatively well in ensuring equitable access and reasonable levels of quality. This is not the case in low-income countries.

Private Health-Care Provision In Low-Income Countries

Although there is broad agreement that the private sector plays an important role in the delivery of health services in low-income countries, there remains much debate on how to measure this role, and as a result, there is limited consolidated evidence. The role of private expenditure for health care changes relatively systematically, becoming less important as national income increases (Musgrove et al., 2002). The same cannot be concluded for private service provision, which appears to be unrelated to the level of private financing.

Low-income countries are characterized by ineffective regulation, small and often fragmented national service delivery programs, and the near total lack of public financing transfers to private for-profit providers. As a result, the role of private health providers varies greatly, reflecting a combination of historical and political priorities and the spontaneous demand of the population.

Consolidated information on providers is limited, and national data on private provision must be questioned, both because they do not include the informal or ‘‘less than fully qualified’’ providers (Berman, 1998) and because biases in reporting ignore the impact of dual employment, which can miss the private clinics of providers with concurrent public employment and also show providers as active in government facilities even if never present (Ensor and Witter, 2000; Hongoro and Kumaranayake, 2000).

As a result of the poor supply of data in low-income countries, utilization measures and payment data (from household surveys) are often used as a proxy. Demographic and health surveys provide an indication of the high importance of private providers as a source of health care across all income strata in low-income countries (Boone and Zhan, 2007), and national health accounts data offer some insight into the high importance of out-of-pocket expenditure for health care in the same countries. Neither data set alone is sufficient to describe the size, role, or distribution of private providers.

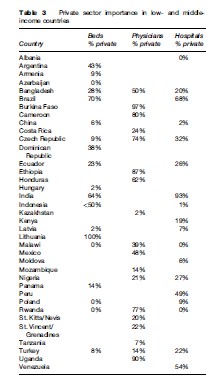

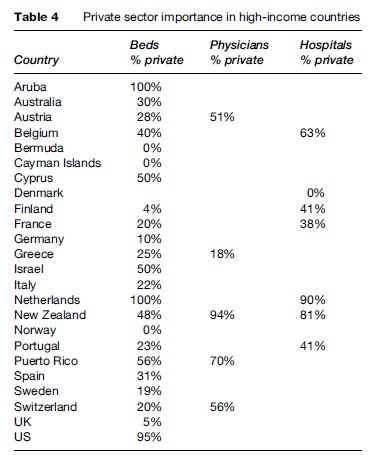

In an attempt to fill this void, Hanson and Berman (1998) measured clinic numbers and hospital beds in both public and private sectors across a number of countries. Using both published and unpublished surveys and government reports, we have recreated this assessment for 61 countries (see Tables 3 and 4). For countries with multiple data points, we examined changes over time. The trend differs by region, but in the rapidly growing economies of South and East Asia we note that for-profit providers and private hospitals are an increasingly important component of the health systems. This is supported by changes in health financing, illustrating that private out-of-pocket financing of health care in these same economies, notably China, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and the Philippines, is both large and increasing.

Tertiary Care

In sub-Saharan Africa, many national health programs were developed out of hospital and clinic networks created by European missionaries during the colonial period. As a result of this legacy, mission facilities are integrated into national health systems in a number of countries, receiving core funding from health ministry budgets as well as subsidized and free medicines, and incorporated into laboratory, referral, and vertical programs. In some South Asian countries, particularly Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Afghanistan, nongovernmental organizations (a special class of nonprofit organization, usually with a humanitarian or philanthropic focus) have taken on an important role with government support, extending the reach of national programs, again with core funding support through longstanding contracts.

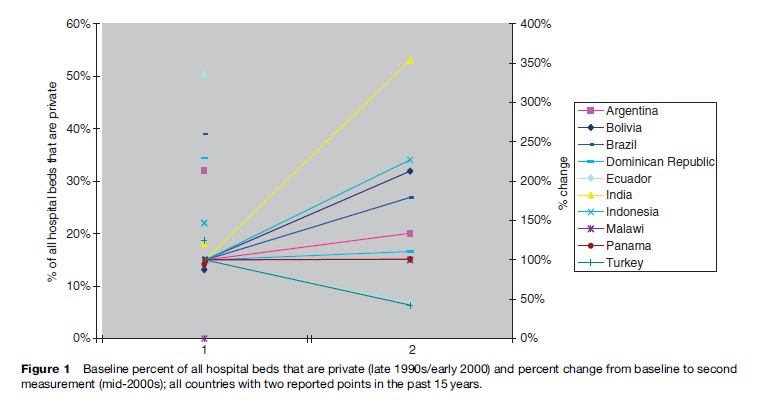

More common are stand-alone for-profit hospitals, observed in almost all low-income countries and serving foreigners, wealthy nationals, and, increasingly, ‘‘medical tourists’’ (Marcelo, 2003). Private hospital numbers are growing in many countries (Figure 1); in Indonesia, for example, they grew from 25% of all facilities in 1997 to more than half of all hospitals today (Thabrany, 2004). World Health Survey (WHS) data consistently shows evidence that in all low-income countries, the private sector is more important in outpatient than in-patient care (WHS, 2002).

Primary Care

Private clinics, pharmacies, consulting rooms, and home care make up the bulk of private practices in developing countries, and the majority of patient interactions with the private sector occur here (WHS, 2002). In China, for example, 70% of all ambulatory care clinics are private (Liu et al., 2006). There are conflicting arguments for when and why this is the case, but broad agreement that the reasons stem from a combination of accessibility, responsiveness, perceived quality, and opportunity cost (Castro-Leal et al., 2000).

Where data are available, they indicate that the private sector is often heavily involved in delivering priority preventative and curative treatments (e.g., public health priorities). In rich countries, this is by design and is linked to policies (e.g., payments, subsidies, regulations); in poor countries, it is often by default, based on demand and social concern, and sometimes is linked to nonprofit delivery. In most poor countries, immunizations are done by public providers, though some countries (e.g., India) give vaccines to private providers to promote coverage (Peters et al., 2002).

Nonprofits

In a number of African countries, religious missions formed the backbone of services during colonial times, and retain a significant role in current care provision. In these countries, mission facilities are de facto government providers, with regular subsidies for salaries and medicines, and full integration into the national reporting and referral systems. Aside from these special cases, however, nonprofits play a small role in overall health systems, for example, representing less than 2% of services in India and less than that in China.

Conclusions

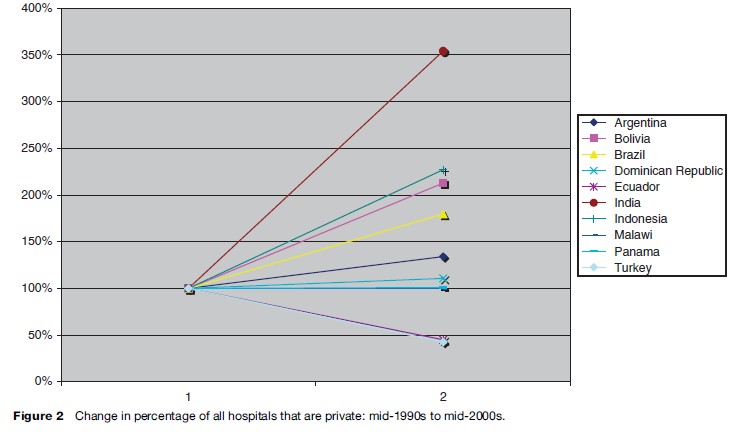

The private sector plays a significant role in the delivery of health care in countries across all income levels (see (Figure 2). This role is higher for ambulatory care than for inpatient care, but beyond that, there are not clear patterns for variation in private sector size by national income, nor by national political leaning. There is some limited indication that the private sector is growing in importance in many places, and attention is increasingly, and appropriately, being paid to understanding how governments can work effectively with private individuals and institutions in order to promote public health goals.

In most instances, collaboration must be based upon an improved understanding of the private sector as a multifaceted grouping of actors, an acknowledgment of the motivation and capacity embodied by the sector, and the value of private care provision, as evidenced by health-seeking behavior of individuals from all wealth strata. Partnerships between private and public sectors have been developed in many countries, both rich and poor, to the benefit of both individual users and the public in general.

Contentious debates about private care provision take place relatively often in the context of development assistance for low-income countries, and to a lesser degree in discussions of health system changes in the United Kingdom and the United States. In most high-income countries, however, private versus public provision is not an explosive issue, both sectors having been incorporated into stable delivery systems with a range of national, insurance, and private financing sources. Where disputes over the role of the private sector develop, debate is often driven by larger political issues of system change (e.g., transition economies, health system decentralization) or reactions of local governments to escalating costs. The general lack of basic data on the efficiency, quality, and equity of private delivery arrangements limits the rigor of such debates, and hampers the development of appropriate policy and program planning. Further data collection and studies are needed to inform and support strategies that engage the private sector in the achievement of public health goals.

Bibliography:

- Berman P (1998) Rethinking healthcare systems: Private healthcare provision in India. World Development 26(8): 1463–1479.

- Boone P and Zhan Z (2006) Lowering Child Mortality in Poor Countries: The Power of Knowledgeable Parents. Center for Economic Performance Discussion Paper No. 751. London: London School of Economics and Political Science. http://cep.lse.ac.uk/ pubs/download/dp0751.pdf (accessed October 2007).

- Castro-Leal F, Dayton J, Emery L, and Mehra K (2000) Public spending on health care in Africa: Do the poor benefit? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78(1): 66–74.

- Deber RB (2002) Delivering Healthcare Services: Public, Not-for-Profit or Private? Discussion Paper No 17. n.p.: Commission on the Future of Healthcare in Canada. http://www.teamgrant.ca/M-THAC%20Greatest%20Hits/Bonus%20Tracks/Delivering%20Health%20Care%20Services.pdf (accessed October 2007).

- Deber R, Topp A, and Zakas D (2004) Private Delivery and Public Goals: Mechanisms for Ensuring that Hospitals Meet Public Objectives. Background Paper. n.p.: World Bank.

- Ensor T and Witter S (2000) Health economics in low income countries: adapting to the reality of the unofficial economy. Health Policy 57: 1–13.

- Hanson K and Berman P (1998) Private health care provision in developing countries: A preliminary analysis of levels and composition. Health Policy and Planning 13(3): 195–211.

- Hongoro C and Kumaranayake L (2000) Do they work? Regulating for-profit providers in Zimbabwe. Health Policy and Planning 15(4): 368–377.

- Liu Y, Berman P, Yip W, et al. (2006) Health care in China: The role of non-government providers. Health Policy 77: 212–220.

- Maarse H (2006) The privatization of health care in Europe: An eight-country analysis. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law 31(5): 981–1014.

- Marcelo R (2003) India fosters growing ‘medical tourism’ sector. The Financial Times July 2.

- Musgrove P, Zeramdini R, and Carrin G (2002) Basic patterns in national health expenditure. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 80: 134–142.

- vretveit J (2003) The Changing Public-Private Mix in Nordic Healthcare – An Analysis. Goteborg, Sweden: Nordic School of Public Health.

- Peters DH, Yazbeck AS, Sharma R, Ramana GNV, Pritchett L, and Wagstaff A (2002) Better Health Systems for India’s Poor: Findings, Analysis, and Options. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Saltman R, Busse R, and Figueras J (2004) Social Health Insurance Systems in Western Europe. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Saltman R, Rico A, and Boerma W (2006) Primary Care in the Driver’s Seat. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Thabrany H (2004) Social health insurance in Indonesia: Current status and the plan for national health insurance. In: Sein T (ed.) Regional Overview of Social Health Insurance in South-East Asia, annex 3, pp. 101–162. New Delhi, India, Regional Office for South-East Asia, World Health Organization. http://www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/ Social_Health_Insurance_HSD-274.pdf (accessed October 2007).

- World Health Survey (WHS) (2002) World Health Survey, World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: WHS.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.