This sample Social Epidemiology Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

Social epidemiology is the branch of epidemiology concerned with understanding how social and economic characteristics influence states of health in populations. Recently there has been a resurgence in interest among epidemiologists about the roles that social and economic factors play in determining health, leading to the recent publication of several volumes reviewing major developments in social epidemiology. This interest is by no means new: The study of socioeconomic conditions and health was a principal concern when epidemiology emerged as a formal discipline in Europe during the nineteenth century, and has remained at the forefront of thinking about population health in various quarters of the discipline since that time.

The renewed interest in social epidemiology has led to major advances in our understanding of the associations between social and economic inequalities and adverse health outcomes. There are consistent and compelling data from the United States and Europe indicating that individuals in the lowest income groups have mortality rates at least two to three times greater than those in the highest. Associations between social inequality and health have been demonstrated in prospective studies from a range of settings, and a number of distinct mechanisms have been postulated to explain the observed associations. As a result, many contemporary epidemiologists have come to recognize social inequalities, and socioeconomic position in particular, as among the most pervasive and persistent factors in determining morbidity and mortality. Though less definitive, there is also evidence to suggest that individuals with less social support suffer from greater morbidity and mortality than individuals with better developed social networks.

Along with these advances, the study of social factors and health has presented important challenges to epidemiology as a discipline. The conceptual and methodological approaches that characterize modern epidemiology are ideal for investigating causes of disease among individuals within populations. But this risk factor approach may be less well suited to research into social and economic factors – especially for understanding how factors operating at different levels of social organization influence the health of populations, or how dynamic temporal processes impact upon health across the life course. Social epidemiologists are among the leaders in addressing these conceptual and methodological challenges, suggesting that social epidemiology has an important place in the future of the discipline.

History Of Social And Economic Determinants Within Epidemiology

Although the term social epidemiology was coined only in 1950, observations of the association between the health of populations and their social and economic conditions can be traced back to the earliest examples of what we would today consider epidemiological thinking. As the discipline emerged formally in the nineteenth century, social factors were prominent in epidemiology’s view of the determinants of population health. A brief overview of the history of social epidemiology demonstrates that although social issues ebbed from the forefront of epidemiological thinking during much of the twentieth century, their current popularity among epidemiologists is actually a rebirth of sorts.

Origins Of Social Epidemiology

Early forerunners of epidemiology presented ideas that today resonate strongly with social epidemiologists, as the integrated nature of human health, lifestyle, and position within the social order lay close to the core of Western medical thinking through the late Renaissance. For example, during the late seventeenth century, Bernardino Ramazzini examined the links between particular occupations and specific health disorders. In addition to its seminal place in occupational epidemiology, his De Morbis Artificum (1700) may be considered among the earliest works on the link between occupational status, social position, and health.

Societal factors were prominently featured as determinants of health when epidemiology emerged as a formal discipline in Europe during the nineteenth century. In France, Louis Rene Villerme’s study of mortality in Paris (1826) described the patterns of poverty and mortality across the city’s wards; his finding of a continuous relationship between poverty and mortality – with poorer neighborhoods having worse health than wealthier ones across all levels of wealth – is the first evidence of the graded relationship that has since been widely documented (Kreiger, 2001). In England, William Farr analyzed the association between mortality and density of urban housing using statistical evidence; he ventured beyond basic descriptions to explore the mechanisms that may link poverty and health and how these may be intervened upon.

Social epidemiology traces a separate strand of its history to the origins of sociology in the late nineteenth century. The earliest sociologists made important contributions to thinking about how population-level characteristics could influence individual health outcomes. In Suicide (1897), Emile Durkheim investigated the social etiology of suicide with particular emphasis on the properties of societies that may operate independently of the characteristics of individuals within them (phenomena that he termed social facts), a topic that has received renewed interest among epidemiologists in recent years.

With the identification of infectious agents as the necessary causes of specific diseases beginning in the late nineteenth century, the focus of much of epidemiology began to shift away from societal factors. However, a number of landmark studies from this period demonstrated how socioeconomic conditions continued to act as critical determinants of population health. In their study of cotton mill workers in South Carolina during 1916–1918, Sydenstricker et al. (1918) developed insights into the role of family income in affecting risk of pellagra, and related this to nutrient intake rather than to the presence of an infectious agent. In their work on disease within birth cohorts, Kermack and McKendrick (1934) hypothesized the importance of early life experiences, including social class, in explaining patterns of morbidity and mortality in adulthood. The role of societal factors in mental health was a focus within sociology and related disciplines during this period, as Farris and Dunham’s ecological studies of Chicago neighborhoods (1939) demonstrated that rates of hospitalization for certain mental illnesses appeared to increase with proximity to urban centers, leading to the hypothesis that social disorganization gives rise to increased risk of schizophrenia.

Socioeconomic Factors During The Modern Risk Factor Era

From the 1950s onward, the changing health profile of industrialized nations spurred a shift in the focus of mainstream epidemiology from infectious to chronic diseases. Social and economic conditions continued to receive attention during this time. The first departments of social medicine were established in Britain after World War II, as Jeremy Morris, Richard Doll, and others had begun to investigate the unequal distribution of chronic disease across social classes. It was during this period that the British 1946 National Survey of Health and Development, its sample stratified by social class, gave rise to a birth cohort that today continues to generate important insights into the perinatal and childhood determinants of adult health.

Although epidemiology was focused largely on the developed world during this time, important findings about the impact of social and economic conditions on health emerged from the developing world. In South Africa, Sidney Kark and his colleagues documented the social and economic structures that facilitated the spread of disease through impoverished populations. His Social Pathology of Syphilis (Kark, 1949) attributed the spread of sexually transmitted infections to migration patterns created by structural economic conditions, foreshadowing the devastating spread of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in recent times. Mervyn Susser, who was mentored by Kark, went on to join anthropologist William Watson in writing Sociology in Medicine (Susser et al., 1962). This book drew examples from both the developing and developed worlds in investigating how the social, cultural, and economic features of populations combine to influence patterns in their health. Today, Kark and Susser are powerful influences on public health research in southern Africa, especially in the field of HIV/AIDS.

By the 1960s, the dramatic improvements in material conditions in the industrialized world, along with the establishment of national health-care systems across much of Europe, led many to believe that socioeconomic factors would become less critical in determining population health. As a result, epidemiologists, particularly in the United States, turned their attention to the role of specific behavioral and environmental factors in causing particular diseases; the archetypal work of this period was the identification of smoking as a cause of (or a risk factor for) lung cancer. Refinements over the last 50 years in epidemiological methods for the study of chronic diseases have propagated a focus on the role played by individuallevel risk factors – environmental exposures, behaviors, genotypes – in disease etiology. The predominance of this risk factor approach saw less and less attention given to the study of social and economic factors in much of American epidemiology. This regression reached a low point during the 1980s, with one prominent epidemiology textbook commenting that socioeconomic position is ‘‘causally related to few if any diseases but is a correlate of many causes’’ (Rothman, 1986: 90).

Although social factors were generally not in the mainstream of epidemiology in the United States, the rise of the risk factor paradigm was nonetheless accompanied by several notable developments in the study of social and economic factors. Another South African and former student of Kark’s, John Cassel, posited that the physiological and psychological stresses of modern society induced generalized vulnerability to disease. His seminal article, ‘The contribution of the social environment to host resistance’ (Cassel, 1976), did much to stimulate the modern body of work on the psychosocial mechanisms through which social and economic factors may influence health. Cassel’s work, along with that of Leo Reeder, Leonard Syme, and others, blended perspectives from the social sciences with traditional epidemiology, producing work that would become the basis of the contemporary field of social epidemiology in the United States.

Recent Advances In Social Epidemiology

After a dormant period, there has been renewed interest in the influence of social and economic factors on health among epidemiologists in the United States during the last decade. This rejuvenation was sparked largely by research from Britain, where social epidemiology had remained at the forefront of public health thinking. The work of Jeremy Morris, Geoffrey Rose, and, later, Michael Marmot was crucial in demonstrating that, despite massive improvements during the second half of the twentieth century in standards of living and population health in the developed world, the social inequalities in health that had preoccupied the earliest epidemiologists a century before were still very much present.

During this recent, rapid expansion in epidemiological research on social inequalities and health, findings for the major associations linking specific socioeconomic factors with increased morbidity and mortality have been refined, and new areas of inquiry have emerged. The conceptualization and measurement of social and economic factors has evolved considerably, and in some instances, researchers have moved beyond documenting general associations toward developing testable hypotheses regarding the pathways involved. Given these far-reaching advances, a complete review of the breadth of social epidemiology is well beyond the scope of this research paper. Instead, we focus on three overlapping forms of social inequality that are at the heart of contemporary social epidemiology: Socioeconomic position, social networks, and discrimination; we include a discussion of the mechanisms that have been put forward by epidemiologists to explain these well-established associations.

Socioeconomic Position

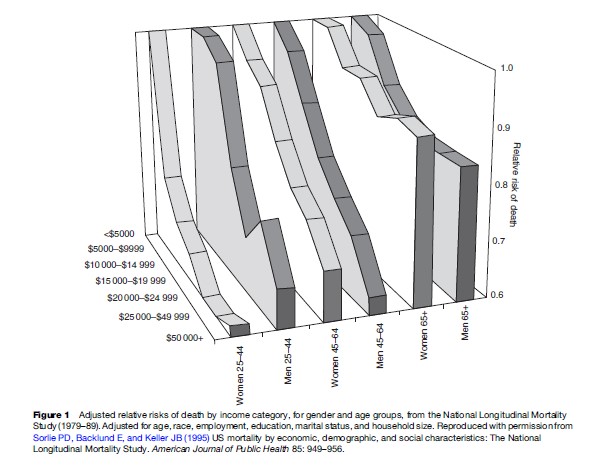

The relationship between poverty and disease has been the primary focus of most contemporary social epidemiology, with considerable attention devoted to more detailed descriptions of and preliminary explanations for an association that has been noted for centuries. The general relationship is simple: There is a large body of literature that demonstrates that individuals who are of a higher socioeconomic position are generally healthier than individuals of a lower socioeconomic position. For example, Sorlie et al.’s (1995) analysis of the National Longitudinal Mortality Study, conducted in the United States between 1979 and 1989, showed that after adjusting for the effects of age, race, and education, the risk of death among men in the lowest income category was approximately three times that of men in the highest income category (Figure 1) (the effect was slightly less among women).

Hundreds of studies have shown similar differences in morbidity and mortality according to absolute socioeconomic position across a range of different populations; by all historical accounts, this association has remained constant for at least several centuries, despite dramatic improvements in both population health and material wealth. This overwhelming consistency and persistence has led some researchers to comment that the association between socioeconomic position and health is the most reliable finding in all of epidemiology.

One important feature of the association between socioeconomic position and health is that it follows a clear monotonic curve. Rather than exhibiting a threshold effect, in which lower socioeconomic position is associated with poorer health only below a certain level of poverty, almost all of the available evidence indicates that lower socioeconomic position is associated with poorer health across all levels of socioeconomic position. This graded association has important implications for possible explanations of the link between socioeconomic position and health. While absolute material conditions may readily explain differences in health between the poorest and wealthiest members of a population, the factors that lead to the differences in health between the highest and second-highest socioeconomic strata are thought to be more complex.

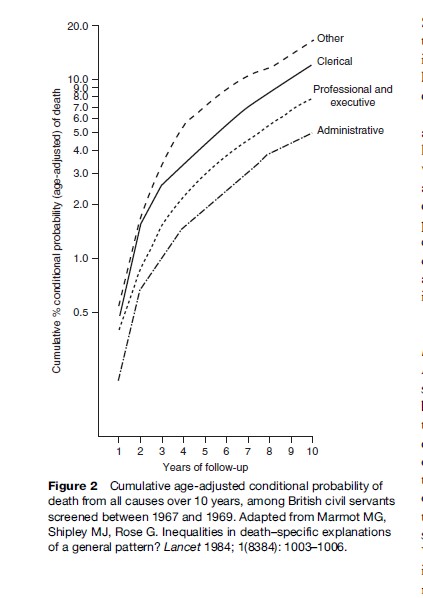

Related to socioeconomic position, the link between occupational category and health is of particular interest in social epidemiology. Growing evidence suggests that systematic health differences exist between occupational groups, even among occupations with similar material working conditions and physical exposures, with workers of higher position generally enjoying better health. Important insights into the relationship between employment and health come from the Whitehall studies of British civil servants led by Michael Marmot and others. The original Whitehall study (Marmot et al., 1984) demonstrated that the lowest grade of civil servants had approximately three times the risk of death compared to the highest grade (Figure 2).

This gradient was also apparent for cause-specific mortality and was explained only in part by traditional risk factors such as smoking, blood pressure, and plasma cholesterol. The second Whitehall study has suggested that occupational factors such as low job control are substantial predictors of the increased risk of coronary heart disease, stronger predictors, in fact, than many traditional coronary risk factors. The Whitehall studies are unique in that marked gradations in health are apparent within a relatively homogeneous population of office workers, suggesting that occupational and socioeconomic factors may impact health even within groups that are not exposed to material poverty.

Measurement Of Socioeconomic Position And Health Outcomes

A wide array of measures of socioeconomic position has been employed by sociologists and epidemiologists, and underlying this are a number of different ways to conceptualize socioeconomic stratification. Among the many different approaches that have been used, a loose distinction can be drawn between approaches based on social class and those based on socioeconomic status. The social class approach generally sees individuals as operating in different formal roles within a structured society, and these roles are reflected by well-defined class measures that tend to be categorical in nature and focus on the relation to means of economic production. To measure social class, preexisting occupational categories are commonly used, ranging from simple distinction between manual and nonmanual employment to complex class measures developed to facilitate international comparisons. Measurements based on socioeconomic status seek to incorporate several different dimensions of an individual’s position within society; the most common measures focus on individual income (representing economic status), education (representing social status), and occupation (representing work prestige) as indicators of socioeconomic position. These three domains overlap substantially, and in many instances, one measure is used as a proxy for a broader construct of socioeconomic status.

In addition to variations in the conceptualization of socioeconomic position, the measures employed by epidemiologists are often adapted to the particular contexts of a given study population, with different measures considered more or less appropriate in specific settings. One important example of this is the measurement of the assets of an individual or household, including resources owned (such as a television or refrigerator) or accessed (such as bank accounts). Households’ assets may be summarized to form an asset index that provides a robust measure of wealth that is commonly used in developing country settings and for cross-country research (for instance, in Demographic and Health Surveys). The range of constructs and measurements used may also result from researchers’ use of data collected for another purpose, limiting the ability to develop the most appropriate measurements of the construct of interest. Further, the diversity of measurements reflects the increasing complexity of the constructs themselves; as social and economic positioning in contemporary societies grows more intricate and dynamic, researchers develop new measures to adapt to this complexity. Ultimately, measures of socioeconomic position strike a balance between the data that are available, the most appropriate measures for the population under study, and investigators’ underlying conceptualization of socioeconomic position.

A diverse set of health outcomes has been associated with socioeconomic position. Mortality is the most commonly used outcome; all-cause mortality is a robust indicator of health that is unlikely to be subject to some of the biases that may threaten the validity of epidemiologic studies. In addition, the association between socioeconomic position and cause-specific mortality and morbidity has been studied in detail for almost every class of disease. In some instances, the association has been extended to measures of subclinical disease, most notably for psychiatric and cardiovascular outcomes. Socioeconomic position has also been shown to be linked to negative health outcomes during pregnancy and infancy, as well as among the elderly, and the associations have also been documented using measures of physical disability and self-reported health.

It is important to note that there are variations in the association between socioeconomic position and particular health outcomes, including a handful of situations where particular diseases may appear more common among individuals of higher socioeconomic position. But despite these variations, the vast majority of the evidence points to parallel gradients of multiple measures of socioeconomic position and a range of adverse health outcomes. The strength and consistency of the overall association across this diversity of measures provides important evidence for the veracity of the overall effect.

Income Inequality

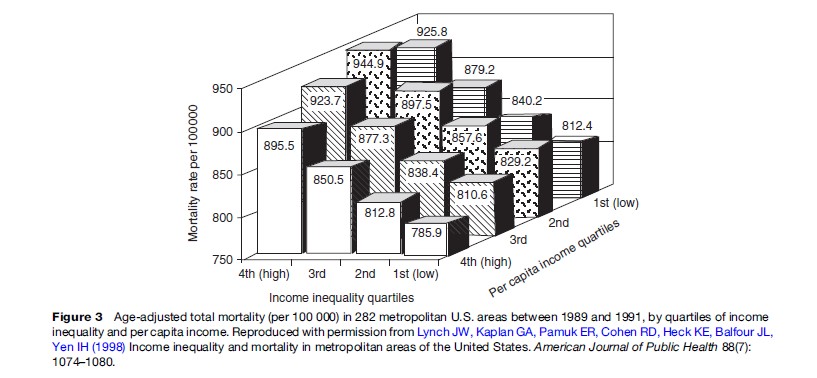

A widely debated insight from the study of socioeconomic stratification and health is the possible role of the distribution of wealth within a population as a determinant of that population’s health. Several researchers have used data from ecological studies (in which nations, counties,

Years of follow-up or other population groupings are the unit of analysis) to suggest that societies with less equitable distributions of wealth tend to be of poorer health, independent of the absolute wealth of the population, which is itself strongly linked to the health of populations. Richard Wilkinson’s studies of the correlation between income inequality within industrialized nations and mortality rates (Wilkinson, 1996) are perhaps the most widely known example of this approach. Other researchers have investigated the association of income inequality and health in different settings and using different units of population with mixed results. The most compelling support for the association between income inequality and health comes from analyses of income distribution and mortality among states and counties and cities within the Unites States (Figure 3).

As with socioeconomic status in general, a number of measures have been used to gauge income inequality. The most common include the Gini coefficient (a unitless measure of the degree of income inequality in the population) and the Robin Hood Index (the proportion of all income that must be moved from the wealthiest households to the poorest in order to achieve perfect income equality); generally, these measures of income are highly correlated and do not generate substantially different results.

Part of the association between income inequality and health outcomes is accounted for by absolute income: Levels of absolute poverty are typically greater in societies with greater imbalances in income distribution. However, several studies have suggested that the association between income inequality and health persists after adjustment for individual-level income. It is important to note that, compared to the effects of socioeconomic position on health status, the impact of income inequality appears to be relatively small. Nonetheless, the study of income inequality and health is an important avenue of inquiry within social epidemiology, including research into social capital and the psychosocial impacts of socioeconomic conditions on health.

Explanations For The General Association

One of the principal challenges encountered by epidemiologists studying social and economic inequalities over the past 20 years has been to explain the observed links between socioeconomic inequalities, and socioeconomic position in particular, and health. Which pathways may account for the general association is much debated. Here we review the possibility of spurious relationships and then discuss three of the most prominent explanations.

In the first place, the observed associations may not be causal in nature. For example, some third variable or variables may confound the associations documented between various social inequalities and health. It is unclear, however, which factors could account for these associations across the range of exposure measures, health outcomes, geographic settings, and historical periods in which they have been demonstrated. Moreover, in most studies that adjust for numerous confounding variables, these associations persist. Another possible alternative explanation is that the observed associations are driven by social selection rather than causation: Morbidity leads to reduced socioeconomic position, rather than the other way around. While this may be particularly relevant for chronic illnesses or those with sustained subclinical forms, this explanation is rendered implausible by numerous prospective studies that examine social and/or economic conditions prior to the onset of disease (or death). Although it is important to recognize the potential for alternative explanations in evaluating the results of every study, neither confounding nor reverse causation appears capable of explaining the body of evidence linking socioeconomic position and health.

One common explanation for the association is that the increased frequency of particular individual-level risk factors in settings of low socioeconomic position, most notably behaviors and environmental exposures, leads to increased risk of disease and death. High-risk behaviors – such as smoking, poor diet, reduced physical activity, and increased alcohol consumption – frequently appear more common among poorer individuals. Indeed, in many settings, the pervasiveness of these lifestyle factors may lead to them being considered normative. Similarly, in many cases poorer communities are more commonly exposed to environmental agents involved in the etiology of particular diseases. But while high-risk behaviors and environmental exposures are important determinants of health, and are often strongly correlated with socioeconomic position, it seems unlikely that individual behaviors can adequately explain the observed associations between social inequalities and health. Empirically, the associations between social inequalities and health typically persist even after accounting for an array of individuallevel behavioral risk factors, a finding that is seen most clearly in the Whitehall studies (discussed in the section titled ‘Socioeconomic position’). An explanatory approach focused solely on individual behavior neglects the impact of social contexts on individual health and does account for the role that economic conditions may play in creating the material circumstances that shape individual action.

Looking beyond such explanations, several researchers have suggested that socioeconomic inequalities give rise to increased psychosocial stress, which induces increased physiological responses, which then contribute to poorer health. This line of thinking emphasizes the relative position of individuals within socioeconomic hierarchies as distinct from their absolute wealth or poverty. The epidemiological data supporting this mechanism is drawn from the ecological studies of income inequality and individual-level studies of relative socioeconomic position (such as the Whitehall studies) discussed in the section titled ‘Socioeconomic position,’ both of which suggest that location within a socioeconomic hierarchy makes an important contribution to health status. Based on this evidence, Wilkinson (1996) and others have hypothesized that perceptions of relative inequality increase psychosocial stress, which may affect physical health via various neuroendocrinal mechanisms (sometimes referred to as allostatic load); individuals positioned lower in the hierarchy suffer greater psychosocial stress, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. This theory is supported by studies of nonhuman primates, suggesting that even when material and lifestyle factors are controlled in an experimental setting, individuals positioned lower in the hierarchy experience worse health. Although it represents an important avenue for future exploration, it is still unclear whether the etiological mechanisms related to psychosocial stress are important mediators of the effect of social inequalities.

A third set of approaches to explaining the observed association between socioeconomic inequalities and health emphasizes absolute socioeconomic position, and how this relates to the material conditions of individuals and populations. At the individual level, higher socioeconomic position (for instance, greater individual income) is important in reducing diverse risks associated with numerous adverse health outcomes. For example, increased socioeconomic position affords access to healthy diets, improved health care (including preventive health care, such as screening programs), better working conditions, and leisure time that may be used for exercise or relaxation. In addition to the individualistic effects of socioeconomic position on health, there are also contextual benefits associated with higher socioeconomic position that operate at the community or population-level, such as improved public services and reduced community crime. The mechanisms that may be included here are diverse, from psychosocial elements, such as quality of residential life, to more traditional exposures, such as environmental toxins.

In understanding how absolute socioeconomic position and related material conditions may affect health, Link and Phelan (1995) have introduced the concept of socioeconomic status as a fundamental cause of adverse health outcomes. Citing the durability of the association of socioeconomic position and health through time despite radical changes in the health of populations and the major causes of disease, this explanation suggests that socioeconomic position embodies an array of material and social resources that could be employed in a range of manners and settings to avoid risks of morbidity and mortality. Despite changing health threats and the emergence of new health technologies, individuals of greater socioeconomic status are consistently better positioned to avoid risk factors for disease – both in terms of behaviors and environmental exposures – and receive better health care once disease occurs. The fundamental cause concept cuts across disease categories and may encompass a diverse range of potential pathways, including the behavioral and psychosocial explanations discussed above.

Social Connections

The way in which social connections and support systems affect health is a major avenue of inquiry within social epidemiology. The findings here are more varied, and perhaps more subtle, than in the case of socioeconomic position (where the general association is well-established); the precise nature of the association depends heavily on the social connections measured, the societal contexts of the populations studied, and the health outcomes involved. And while many social epidemiologists have focused on the positive impacts that increased social connections may confer on health status, the associations here appear to be far more complex than that.

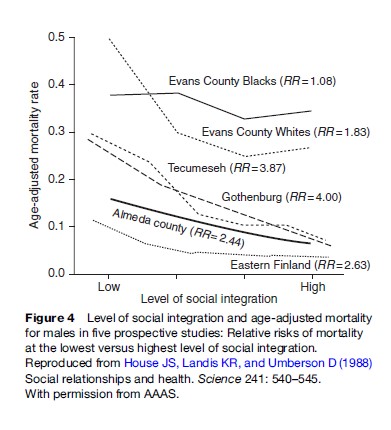

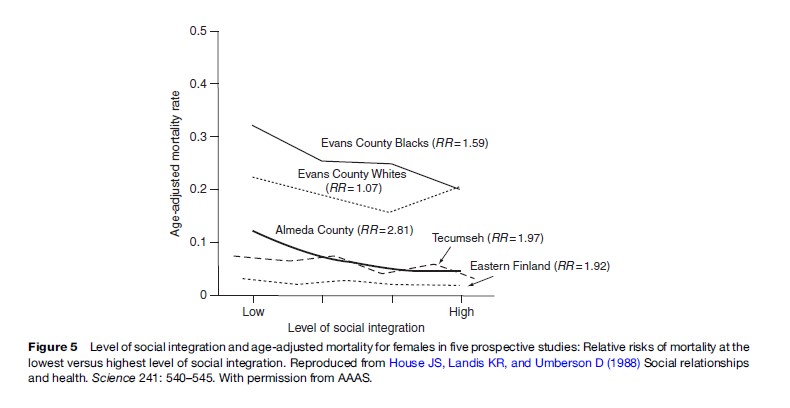

A series of prospective studies conducted in the last 25 years have provided strong evidence that better developed social networks are associated with reduced all-cause mortality. Perhaps the best known of these is the Alameda County study of Berkman and Syme (1979). Between 1965 and 1974, individuals with reduced social integration (based on marital status, community group membership, and contacts with family and friends) were two to three times more likely to die than individuals with increased social integration; this association persisted after adjustment for various self-reported high-risk health behaviors. In a second landmark survey, House (1982) used composite measures of social relationships to show that individuals with reduced social ties when interviewed in the late 1960s were about twice as likely to die over the next 12 years, compared to individuals with increased social ties. Adjustment for biological health measures at baseline, including blood pressure, cholesterol, electrocardiogram results, and lung function, did not dispel this association. Similar results have been found in a number of other prospective studies from Europe, the United States, and Japan, despite the markedly different populations, background mortality rates, and causes of death across these studies (Figures 4 and 5).

In addition, more recent studies have shown that a paucity of social connections is associated with increased mortality from a range of specific causes, most notably cardiovascular disease and stroke. To quantify social networks and connections, a wide range of measures have been employed; some approaches have proved to be more broadly applicable than others. Given the highly context specific nature of social ties, it is unlikely that any one set of measures can be employed universally across all research settings.

Although this evidence is highly suggestive of positive health benefits for social connectedness, several important questions of interpretation remain. In many instances, it is unclear whether the presence of strong social networks acts to prevent the onset of disease or to improve survival after onset. Typically the association appears to be stronger in men than in women and to vary according to urban or rural location. Moreover, exactly which aspects of social networks might confer health benefits is much debated. Psychosocial support, possibly conferring a reduction in the impact of stressful life events, has been the most widely discussed mechanism. Other potential pathways through which social networks lead to improved health status may include enhanced social influence and agency to prevent or treat illness, increased social stimulation and interaction, and/or increased access to material assistance in times of need.

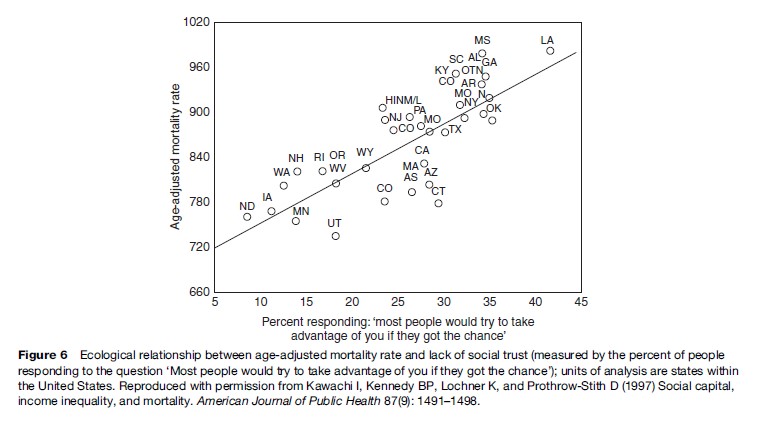

Related to the research at the individual level into the positive impacts of social networks on health is a diverse body of work on how the collective social characteristics of a population (rather than the social characteristics of individuals within the population) impact on health. These group properties are sometimes referred to as social capital: ‘‘the ability to secure benefits through membership in networks and other social structures’’ (Portes, 1998: 8). While the term social capital is deployed in varying ways (and is by no means limited to public health), in the last few years, research findings have emerged that demonstrate a connection between the degree of social integration or cohesion that characterizes communities and the health of those communities. Kawachi and colleagues (1997) demonstrated that age-adjusted mortality rates among U.S. states were strongly correlated with measures of membership in voluntary civic groups, with perceptions of reciprocity in the community, and with perceptions of trust. The inverse relationship between mortality and perceptions of social trust – measured by the percentage of individuals surveyed who agreed that ‘‘most people would try to take advantage of you if they got the chance’’ – is among the most striking findings (Figure 6).

Several studies have found that various measures related to the concept of social capital appear inversely related to income inequality, suggesting that decreased social capital may represent a pathway through which the unequal distribution of income influences health. However, it remains unclear whether group-level associations between social capital and population health are mediated by individual level social connections.

As discussed here, social epidemiologists have focused primarily on the protective effects that social networks may have on health. However, it is important to note that social networks can have significant negative impacts on health, such as when networks promote exposure to infectious agents or high-risk behaviors (or both). Much of our understanding of the way in which social networks may have detrimental effects on the health of populations comes from the mathematical modeling of the spread of disease within populations. Social epidemiology and mathematical modeling have started to converge only recently; the confluence of these approaches to social networks and health, coupling the direct measurement of networks and individuals’ positions within them along with the modeling of disease transmission within populations holds promise for the future.

Discrimination

The body of epidemiological research into the health disparities between different racial or ethnic groups has grown considerably in the past decade, providing powerful evidence that mortality rates within the United States are higher among African-Americans and other minority groups, relative to the general population. In one of the best-known analyses of race and health, McCord and Freeman (1990) showed that age-standardized death rates in Harlem (a predominantly African-American community in New York City) were more than twice that of Whites living in the United States. This finding was confirmed by the National Longitudinal Mortality Survey, which showed that mortality rates among African-Americans were appreciably higher than among Whites, despite statistical adjustment for employment, income, education, marital status, and household size; the differences are particularly pronounced among younger age groups. In addition to findings for mortality differences, similar associations have been demonstrated for a number of adverse health outcomes, including hypertension and cardiovascular disease as well as infant mortality and low birth weight. As in the case of the association between ethnicity and mortality, these disease-specific associations typically persist after adjustment for multiple indicators of socioeconomic position.

While differences in morbidity and mortality among ethnic groups are widely acknowledged, the explanations for these differences are far more contentious. Some researchers have argued that ethnic differences in health are due to genetic predispositions, but there is little evidence for this in any but a handful of conditions. Others have pointed to shortcomings in epidemiological methods, suggesting that much of the observed association between race and health may result from the mismeasurement of, and subsequent inadequate statistical adjustment for, the effect of socioeconomic status on health. While this explanation may be plausible in some instances, the ubiquity of ethnic differences in health within socioeconomic strata as well as across time and place point to an independent association.

In explaining these differences in morbidity and mortality, Sherman James (1987), Nancy Krieger (1999) and others have taken a broader view of racial differences in health and posited ethnic discrimination (i.e., racism), rather than ethnicity itself, as the principal factor responsible for the observed associations between race and health. In this light, socioeconomic differentials may be part of the pathway through which racial discrimination affects health, rather than a confounder to be adjusted for in analysis.

Systematic discrimination and historical inequalities could act in several ways. Reduced access to and quality of health care are commonly cited explanations for the association between minority status and increased morbidity and mortality, particularly in the United States. Other mechanisms may include the increased stress and psychosocial burden associated with discrimination, as well as the reduced access to material resources among most minority groups. As epidemiological research into ethnic disparities in health expands, it is clear that the general association between racial categories and adverse health outcomes can provide only indirect evidence of the effects of racial discrimination. Further refinements in the conceptualization and measurement of discrimination are required to promote our understanding of the association between ethnicity and health.

Emerging Concepts Within Social Epidemiology

The recent advances within social epidemiology have been paralleled by a more general series of commentaries on epidemiological approaches under the risk factor paradigm. These critiques have focused primarily on the perceived preoccupation of contemporary epidemiology with how individual-level factors shape health and the subsequent difficulties epidemiologists face in researching determinants of health that are not easily reduced to individual-level terms (Schwartz et al., 1999). Although these commentaries refer to epidemiology as a discipline, they are especially relevant to, and have been motivated in part by, the study of social and economic inequalities. Here we focus on two particular areas of critique and the advances which have emerged from them: Levels of social organization and the diachronic processes shaping individual and population health.

Levels Of Social Organization

Several commentaries have suggested that contemporary epidemiology is focused too much on etiologic factors that operate among individuals and too little on other, potentially relevant levels of social or biological organization. With respect to social epidemiology, this criticism challenges the focus on social and economic variables that are conceptualized and measured at the individual level (e.g., individual income or education). While important, this focus fails to account for the possibility that social inequalities operating at other levels of organization – such as the neighborhood, society, or even globally – may be of relevance in shaping health, separate from their individual-level counterparts. Different levels of social organization are often implicit within social epidemiological research, but most studies fail to specify the level(s) that are involved in conceptualizing and analyzing social inequalities. For instance, measures of average community income (e.g., income per capita) may be employed in some studies as a proxy for individual-level incomes within communities; in this case, a group-level variable is being used to capture an individual-level construct. Yet in other instances, the same measure of community income may be intended to reflect aspects of the wealth of the community – such as infrastructure development – that are distinct from (but may be related to) the individual-level measure of income. Other concepts in social epidemiology, such as social capital or income inequality, are inherently features of groups. In recognizing the different levels of social organization that are involved in their hypotheses and measurements, social epidemiologists are beginning to develop a framework for thinking about how social and economic characteristics of individuals, communities, and/ or societies may each contribute to health in unique ways; this line of thinking provides a more complex – and more fertile – conceptual approach than analyses focused exclusively at the individual level.

The ability to think across levels of social organization greatly expands epidemiologists’ potential for understanding the determinants of individual and population health. For example, the course and outcome of schizophrenia varies markedly between developed and developing countries, with the disease appearing more benign (on average) in developing country settings. If the factors impacting the outcome of schizophrenia are viewed solely as the characteristics of individuals, this fact appears counterintuitive, as modern treatments with demonstrated efficacy are much more widely available in the developed world. In explaining this difference, epidemiologists have turned to the possibility that social and economic processes may help lead to improved schizophrenia outcomes in developing-country settings.

Considering the causes of disease operating across different levels of organization raises the possibility that groups may have features, beyond the aggregated characteristics of individuals within them, that can shape health outcomes, a phenomenon frequently referred to as emergent group properties. The ability to conceptualize social and economic factors as group properties that cannot be understood solely as individual-level variables represents an important vehicle for social epidemiologists. In a seminal paper, Sampson (1997) and colleagues demonstrated that the social features of Chicago neighborhoods helped to explain levels of violent crime, independent of the characteristics of the individuals living within them. In a similar vein, a growing number of epidemiological studies are investigating how the characteristics of particular social environments influence health outcomes independent of the characteristics of individuals living in those locations. Diez Roux (2001) demonstrated that the socioeconomic environment of neighborhoods was associated with substantially increased risk of both coronary heart disease and coronary events, even after statistical adjustment for individual-level socioeconomic status, smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels. In the Alameda County study, Yen and Kaplan (1999) defined local social environments using area measures of socioeconomic status, the presence of commercial stores, and the condition of housing and the physical environment. They demonstrated that all-cause mortality and self-reported health status were associated with each of these parameters independently of individual-level risk factors. These and other studies have helped to show that communities or neighborhoods frequently encapsulate a range of structural properties that may influence health; however, researchers are only beginning to shed light on how this is so, and approaches to understand these associations between social areas and health are at the cutting edge of social epidemiology.

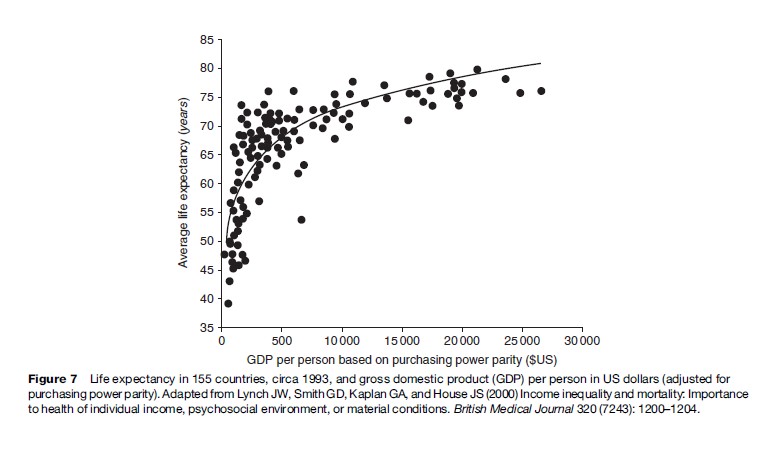

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for the determination of health and disease at different levels of social organization comes from the global view of morbidity and mortality. As presented above, the bulk of epidemiologic research into socioeconomic position and health has focused within populations, and particularly within industrialized nations. While this approach has generated important insights, social epidemiology has largely ignored the global inequities that clearly demonstrate the effects of poverty on health (Figure 7).

As these inequalities in global health gain increasing political and economic attention, the need to better understand – and begin to address – them presents a central challenge to epidemiology. For social epidemiologists, this means moving beyond the simple characterization of individual-level exposure and outcome variables, toward incorporating varying units of social organization into research to understand the social and economic properties of communities, nations, and continents that help to determine morbidity and mortality.

Diachronic Processes

In parallel with the difficulties in recognizing various levels of social organization, epidemiology as a discipline has been challenged to understand how processes operating through time – historical and individual – shape the disease experience of populations and individuals. With respect to social epidemiology, this critique challenges the dominant focus on social and economic factors, which are treated as static phenomena that are temporally proximate to disease, with researchers viewing social inequalities during adulthood as being of primary concern in understanding the causes of adult disease and death. There has been relatively little attention paid until recently to how social and economic forces at play earlier in life may shape later risk of morbidity and mortality.

In addressing this critique, epidemiologists are focusing increasingly on the potential impact of socioeconomic conditions in early-life on disease during adulthood. Cohorts in Britain and the United States have demonstrated links between social class at different stages of the life course and adult mortality, as well as with a number of markers for cardiovascular disease. In some instances, these associations persist after accounting for adult socioeconomic position, though given the clear links between childhood and adult socioeconomic position, the appropriateness of traditional statistical adjustment for adult socioeconomic circumstances remains unclear. Debate as to how these effects may operate is considerable. Several researchers have suggested that insults during critical periods in early life initiate physiological processes culminating in later morbidity. Others have hypothesized that early life experiences help to shape adult circumstances, but do not have an independent impact on health outcomes. Bridging these views, Davey Smith and others have proposed a life course approach, in which disadvantage in early life sets in motion a cascade of subsequent experiences that accumulate over time to produce disease in adulthood. To date, evidence exists to support each of these hypotheses. To discriminate between them, new conceptual and analytical approaches will be required.

Although social epidemiology is gradually rediscovering the importance of diachronic perspectives, psychiatric epidemiologists have made important advances in understanding the determinants of health operating over the life course. For instance, there is a growing body of evidence to show that developmental antecedents in early childhood are strongly associated with a range of subsequent psychiatric symptoms. By developing testable hypotheses of the mechanisms that may mediate such associations, Sheppard Kellam (1997), Jane Costello, and others have advanced our understanding of how social contexts in early life shape later behaviors. In doing so, this body of research presents a useful model for social epidemiologists to explore how social contexts throughout the life course may impact a range of health outcomes.

Conclusion

A diverse body of epidemiologic evidence leaves little doubt that economic and social inequalities are strong and consistent determinants of morbidity and mortality. Recent advances have improved our understanding of the pathways through which these parameters affect health and refined how these inequalities are conceptualized and measured. As the full implications of the notion that human beings and their health states are constituted in both biological and social terms become more widely acknowledged within epidemiology, social epidemiology is likely to become an increasingly integral aspect of the broader discipline. The perspectives that social epidemiology brings to the study of the determinants of individual and population health are likely to continue to shape both the way in which epidemiology conceptualizes the causes of disease and how epidemiologists respond in practice to public health concerns.

Bibliography:

- Berkman LF and Syme SL (1979) Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology 109: 186–204.

- Cassel J (1976) The contribution of the social environment to host resistance: The Fourth Wade Hampton Frost Lecture. American Journal of Epidemiology 104: 107–123.

- Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, et al. (2001) Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. New England Journal of Medicine 345: 99–106.

- Durkheim E (1951 [1897]) Suicide: A Study in Sociology. New York: The Free Press.

- Farris RE and Dunham HW (1939) Mental Disorders in Urban Areas. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- House JS, Landis KR, and Umberson D (1988) Social relationships and health. Science 241: 540–545.

- House JS, Robbins C, and Metzner HL (1982) The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology 116: 123–140.

- James SA, Strogatz DS, Wing SB, and Ramsey DL (1987) Socioeconomic status, John Henryism, and hypertension in blacks and whites. American Journal of Epidemiology 126: 664–673.

- Kark SL (1949) The social pathology of syphilis in Africans. South African Medical Journal 23: 77–84.

- Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Lochner K, and Prothrow-Stith D (1997) Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. American Journal of Public Health 87(9): 1491–1498.

- Kellam SG and Van Horn YV (1997) Life course development, community epidemiology, and preventive trials: a scientific structure for prevention research. American Journal of Community Psychology 25: 177–188.

- Kermack O, McKendrick AG, and McKinlay PL (1934) Death-rates in Great Britain and Sweden. Some general regularities and their significance. Lancet i: 698–703.

- Krieger N (1999) Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. International Journal of the Health Services 29: 295–352.

- Krieger N (2001) Historical roots of social epidemiology: socioeconomic gradients in health and contextual analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology 30: 899–900.

- Link BG and Phelan J (1995) Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior special issue, 80–94.

- Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Pamuk ER, et al. (1998) Income inequality and mortality in metropolitan areas of the United States. American Journal of Public Health 88(7): 1074–1080.

- Lynch JW, Smith GD, Kaplan GA, and House JS (2000) Income inequality and mortality: Importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. British Medical Journal 320(7243): 1200–1204.

- Marmot MG, Shipley MJ, and Rose G (1984) Inequalities in death–specific explanations of a general pattern? Lancet 1: 1003–1006.

- McCord C and Freeman HP (1990) Excess mortality in Harlem. New England Journal of Medicine 322: 123–127.

- Portes A (1998) Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 24: 1–24.

- Ramazzini B (1940 [original, 1700]) De morbis artificum Bernardini Ramazzini diatriba, Diseases of workers: the Latin text of 1713 revised, with translation and notes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Rothman K (1986) Modern Epidemiology, 1st edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Rothman KJ (1986) Modern Epidemiology. Boston, MA: Little Brown and Company.

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, and Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277: 918–924.

- Schwartz S, Susser E, and Susser M (1999) A future for epidemiology? Annual Review of Public Health 20: 15–33.

- Sorlie PD, Backlund E, and Keller JB (1995) US mortality by economic, demographic, and social characteristics: The National Longitudinal Mortality Study. American Journal of Public Health 85: 949–956.

- Susser M, Watson W, and Hopper K (1985) Sociology in Medicine, 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sydenstricker E, Wheeler GA, and Goldberger J (1918) Disabling sickness among the population of seven cotton-mill villages of South Carolina in relation to family income. Public Health Reports 33: 2038–2051.

- Villerme LR (1826) Rapport fait par M Villerme, et lu al’Acade mie royal de Medicine, au nom de la Commission de statistique, sur une serie de tableaux relatifs au mouvement de la population dans les douze arrondissements municipaux de la ville de Paris, pendant les cinq annees 1817, 1818, 1819, 1820 et 1821. Archives Generales de Medicine 10: 216–247.

- Wilkinson RG (1996) Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. London: Routledge.

- Yen IH and Kaplan GA (1999) Neighborhood social environment and risk of death: multilevel evidence from the Alameda County Study. American Journal of Epidemiology 149: 898–907.

- Berkman LF and Kawachi I (eds.) (2000) Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Diez Roux AV (2001) Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. American Journal of Public Health 91: 1783–1789.

- Evans RG, Barer ML, and Marmor TR (eds.) (1994) Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not? New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Krieger N (2001) A glossary for social epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 55: 693–700.

- Kuh D and Ben Shlomo Y (1997) A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Leon D and Walt G (2001) Poverty, Inequality and Health: An International Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Link BG and Phelan JC (2000) Evaluating the fundamental cause explanation for social disparities in health. In: Bird C, Conrad P and Fremont A (eds.) The Handbook of Medical Sociology, pp. 33–46. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Marmot M (1999) The Social Determinants of Health. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Myer L, Ehrlich R, and Susser ES (2004) Social epidemiology in South Africa. Epidemiology Reviews 26: 112–123.

- Rose G (1992) The Strategy of Preventative Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.