This sample Syphilis Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Historical Background and Recent Epidemiology

Syphilis (Treponema pallidum) is one of the most intriguing human pathogens. First described as the Great Pox, its true historical origins are unclear. The emergence of syphilis in Europe coincided with the return of Columbus’s crew from the New World in 1493; Dr. Ruy Diaz de Isla (Barcelona) claimed to have treated Vicente Pinon, master of the Nina (Oriel, 1994). Its appearance in Europe has also been ascribed to the spread of the infection from the tropics, the severity of the disease being attributed to its introduction to a nonimmune population. Nevertheless, what is clear is that a major pathological entity appeared in late fifteenth-century Europe, spreading quickly throughout the Continent, and then on to India (1498) and China (1505). The spread of infection was influenced by a combination of factors including socioeconomic change, conflict, and migration. Syphilis affected the whole of society and had far-reaching consequences. The response to the infection – blame, shame, stigma, and intolerance – reflects the attitude of society to sexually transmitted diseases over the subsequent centuries, and anticipates the reaction to the emergence of HIV at the end of the twentieth century. The element of blame in the epidemic of this new virulent disease is clear in the names it was given; terms such as the ‘Italian,’ ‘Spanish,’ and ‘Polish’ disease were coined by neighboring and rival countries, as well as more generic terms such as the ‘Great Pox’ and ‘lues venereum’ (venereal disease). However, it was the word ‘syphilis,’ derived from the name of a shepherd who suffered from the condition in Girolamo Fracastoro’s poem Syphilis Sive Morbus Gallicus, or Syphilis and the French Disease (1530), that came to be used universally. The effect of syphilis on society was profound and has been documented by artists, writers, and historians over the subsequent centuries (Morton, 1990).

From the late Renaissance to the present day, knowledge of the infection has developed in line with advances in anatomy, physiology, microbiology, pharmacology, and epidemiology. The association between syphilis and cardiovascular disease was first described by Lascis (1654–1720), and neurosyphilis and congenital syphilis by Fournier (1832–1914). In the absence of diagnostic methods at that time, the noted Scottish scientist and surgeon John Hunter (1728–93) believed that syphilis and gonorrhoea were the same disease, and it was not until 1838 that Philippe Ricord’s study of 2500 human inoculations showed that syphilis and gonorrhoea in fact had separate etiologies. Ricord also categorized the natural history of syphilitic infection into primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis, the classification that is still used today. Given the huge diversity of presenting symptoms seen at the tertiary stage, there was a temptation to attribute any subsequent illness suffered by a patient to syphilis after an attack of the infection, which led Sir William Osler (1849–1919), considered the ‘Father of Modern Medicine,’ to observe that ‘he who knows syphilis knows medicine.’

As with many areas of venereology, knowledge of syphilis has been guided by advances in diagnostic techniques. In 1906, Wasserman (1866–1925) created a serological test for T. pallidum which allowed a more precise understanding of the burden of disease and the associated clinical manifestations. At the beginning of the twentieth century 20% of the European urban population had syphilis, and in the UK a Royal Commission was set up in 1916 to evaluate the threat to public health posed by syphilis and gonorrhoea. Although the UK National Health Service was not created until 1947, the Royal Commission concluded that only state intervention could effectively address the problem. A network of specialist clinics was created that offered confidential diagnosis, treatment, and management, including partner notification. Motivation for this public health measure came as much from the high morbidity associated with venereal disease experienced by the armed forces in World War I as from a concern for the nation’s sexual health and the high number of hospitalized patients suffering from the long-term consequences of syphilitic infection.

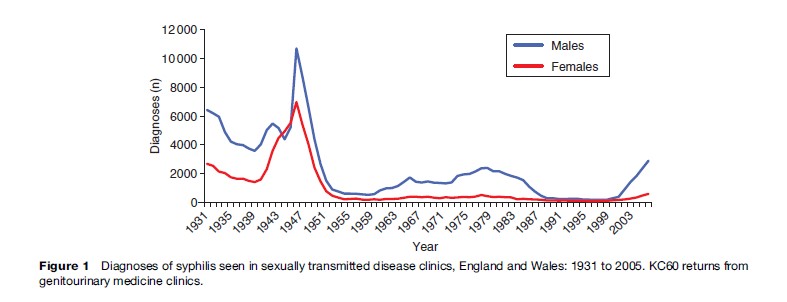

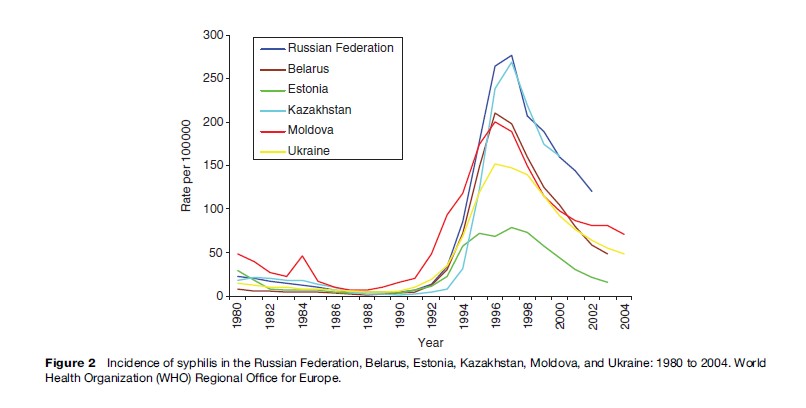

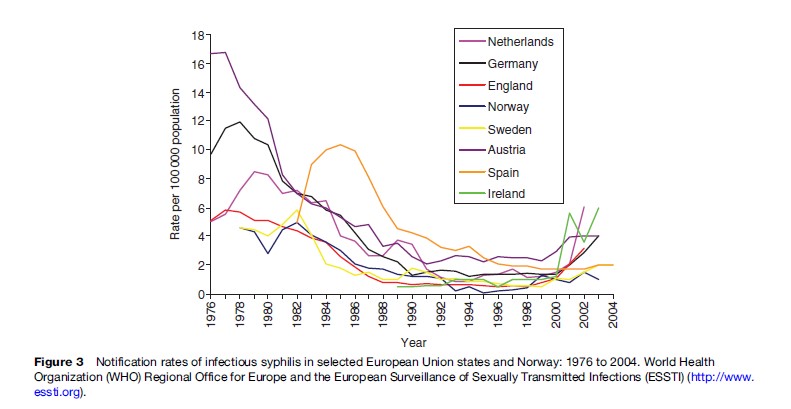

Diagnoses of syphilis fluctuated throughout the twentieth century, influenced by social change, conflict, changing sexual behavior, and developments in health care. In industrialized countries the antibiotic era effectively eliminated syphilitic complications but did not eradicate infection (Figure 1). Industrialized countries experienced a postwar syphilis epidemic which peaked in the mid- 1970s, with prevalence and incidence falling in the face of the behavioral change initiated in the late 1980s by the emerging HIV pandemic. However, since the late 1980s, Western and Eastern Europe have experienced distinctly different syphilis epidemics (Figures 2 and 3). After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, substantial rises were seen in the incidence of syphilis among men and women in the newly independent states. Incidence of infection quickly increased from around 5/100 000 in 1990 to as much as 170/100 000 in 1996, a rate 34 times higher than those seen in Western Europe. The reasons for this increase were rooted in the collapse of the state-run health-care system together with the profound social and economic changes that occurred in these countries. In Western Europe by contrast, syphilis incidence remained relatively stable through the 1990s, but since the end of the decade there has been a dramatic change in incidence. Outbreaks of infectious syphilis have been seen in major cities in Europe, North America, and Australia, which are mainly focused on men who have sex with men (MSM), with a high proportion of cases coinfected with HIV. The epidemiology of syphilis has been influenced by developments in the HIV epidemic and behavioral change in MSM. The availability of effective antiretroviral therapy in 1996 was associated with behavioral change among HIV-positive MSM and an increase in HIV prevalence. The availability of Viagra (sildenafil citrate) may also have increased sexual activity in HIV-positive MSM. There has also been an increase in traditional ‘sexual marketplaces’ such as saunas and cruising grounds, together with a rapid growth in Internet chat rooms, increasing the opportunity for rapid and easy access to new sexual partners. The effect has been to join previously isolated sexual networks, increasing the effective size of the sexual network and reducing the time taken for the epidemic to evolve (Simms et al., 2005). Alongside the syphilis epidemic among MSM, an outbreak in heterosexuals has developed that has been associated with factors including travel to high-prevalence countries, commercial sex work, and illicit drug use. In the UK, the number of cases associated with Eastern Europe has been small, and the proportion of heterosexual cases acquired abroad is similar to that seen in the mid-1990s when incidence was low.

It has been suggested that fluctuations in syphilis epidemics reflect factors such as sexual behavior and availability of clinical services and treatment, but fluctuations are also governed by interactions between the infection and the host immune system. Syphilis stimulates imperfect immunity and mathematical models have shown that the dynamics of syphilis infection have many of the features of the ‘susceptible–infected–recovered’ model of microparasitic infections (Anderson et al., 1992; Grenfell et al., 2001). Essentially, a cyclical pattern of infection emerges over time: epidemics disappear as the number of susceptible individuals falls, and the reproductive rate (R0) falls below 1; the number of individuals in the at-risk group then accumulates, R0 increases, and a new epidemic emerges (Grenfell et al., 2001). This pattern has been seen in the United States on a number of occasions over the past 50 years. The 8-to-11-year cycle seen in the repeat epidemics of primary and secondary syphilis reflects the natural dynamics of the relationship between the infection and the human population (Grassly et al., 2005).

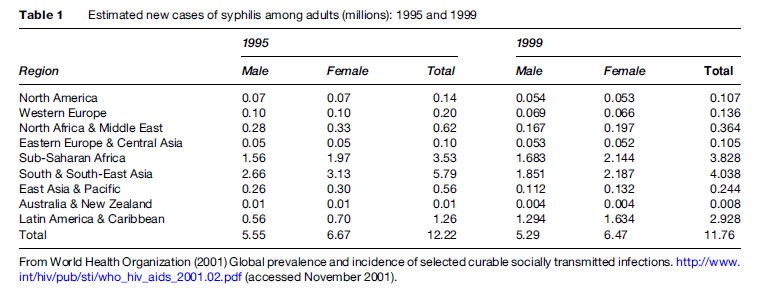

Syphilis is a global infection and the majority of cases are now to be found in the developing world reflecting lack of provision and access to health care, health-seeking behavior, and the global population distribution (Table 1) (WHO, 2006a). The highest prevalences are in sub-Saharan Africa and South and South-East Asia, the lowest in Australia and New Zealand. Although these estimates illustrate the global importance of syphilis, they are biased due to the quality and quantity of the available surveillance data as many countries do not have national surveillance systems. Many prevalence studies have been undertaken within clinical or occupational groups and the detected prevalences vary considerably among settings, locations, and countries. The seroprevalence of maternal syphilis provides an indication of the prevalence of syphilis within the population, and the WHO has estimated the seroprevalences of maternal syphilis to be: 3.9% in the Americas; 1.98% in Africa; 1.5% in Europe; 1.47% in South-East Asia; 1.11% in the Eastern Mediterranean; and 0.7% in the Western Pacific (Stoner et al., 2005).

Diagnosis

The presence of T. pallidum may be detected in lesions or infected lymph nodes in early syphilis using dark field microscopy. Direct fluorescent antibody and nucleic acid amplification tests can be used to detect the presence of T. pallidum in oral samples as well as lesions but could be contaminated with commensal treponemes. The laboratory diagnosis of secondary, latent, and tertiary syphilis is based on serological tests. It is a complex subject and has been the focus of many reviews (Lewis and Young, 2006; Singh and Romanowski, 1999). Essentially diagnosis is based on a combination of non-treponemal and treponemal tests. Non-treponemal tests, such as the rapid plasma regain or venereal disease research laboratories (VDRL) test, are used for screening, with positive results confirmed using a treponemal test, such as the T. pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA). Access to laboratory services can be very limited within the resource-poor countries where most cases of infectious syphilis are seen and many cases are diagnosed clinically and managed syndromically. Point-of-care tests are now commercially available and have been evaluated by the WHO (Peeling, 2006). These simple ‘desk-top’ tests use whole blood, involve no equipment, can be stored at room temperature, and require minimal training. Although these tests cannot distinguish between active infection and past exposure, their value lies in allowing antenatal screening to be undertaken in resource-poor settings, and improving the control of syphilis in adults.

Treatment

Therapy aims to achieve a treponemicidal level of antibiotics. The therapeutic options available depend on the stage of infection, whether there is neurological involvement, and whether the patient is pregnant or infected with HIV. First-line therapy is long-acting penicillin, such as benzathine penicillin G. A level of greater than 0.018 mg/L is treponemicidal whereas a maximal elimination effect is achieved at 0.36 mg/L (Idsoe et al., 1972). Experience from case studies, expert opinion, and the natural history of syphilis (which has a division time of 30 to 33 hours) all indicate that the course of treatment should be once a day for at least 7 days. Treponemes may persist despite effective treatment and may have a role in reactivating the infection in immunosuppressed patients.

A longer duration of therapy may be required in the treatment of late syphilis if the organism is dividing more slowly. Similarly, in early syphilis, infection may persist after apparent successful treatment, so 10 days treatment is given in early syphilis and 17 days in late syphilis or where neurological involvement is seen (BASHH, 2006).

Tetracyclines, such as doxycycline and erythromycin, have been used in the treatment of syphilis. Erythromycin does not penetrate the cerebral spinal fluid or placental barrier well, and resistance to erythromycin has been reported in T. pallidum. The use of 100 mg once or twice daily for 14 days has been shown to be effective in the treatment of infectious syphilis but failures have been reported in the treatment of latent syphilis.

Azithromycin as a single oral dose has good efficacy against other STIs including Chlamydia trachomatis and chancroid. Azithromycin therapy is more convenient to administer than intramuscular benzathine penicillin and might improve syphilis control by allowing treatment to be given in nonclinic and outreach settings. The evidence base for the use of azithromycin in the treatment of syphilis remains poor. Animal studies show good efficacy activity against T. pallidum and uncontrolled studies of longer courses of azithromycin appear to show efficacy in early disease. However, poor transplacental and cerebrospinal fluid penetration are likely to limit the usefulness of azithromycin in pregnancy and late syphilis, respectively, and, to date, only small randomized studies suggest it is efficacious in early syphilis. Macrolides (including azithromycin) remain fourth-line agents for syphilis after penicillin, tetracyclines (such as doxycycline), and cephalosporins (such as ceftriaxone).

Transmission And Clinical Presentation

Syphilis is transmitted through sexual intercourse but infection can also be transmitted vertically resulting in congenital syphilis, and occasionally by blood transfusion and nonsexual contact, such as kissing. The clinical presentation of syphilis is divided into three stages: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary syphilis is characterized by painless papules that develop at the site of inoculation between 9 and 90 days after infection. These quickly ulcerate but heal spontaneously within 6 weeks. Other symptoms, such as localized lymphadenopathy, may also occur. Secondary syphilis, a systemic disease resulting from the dissemination of treponemes through the body, can occur either at the same time as primary syphilis or within 6 months. The clinical manifestations of this stage include generalized lymphadenopathy, rash with lesions on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, fever, mouth ulcers, localized hair loss, condylomata lata (a wartlike growth), and meningitis. Symptoms of infection resolve spontaneously after a period of 3 to 12 weeks. If the patient is pregnant, the fetus can be infected in utero through transplacental passage.

In latent syphilis T. pallidum is still present in the spleen and lymph nodes and may invade the bloodstream, leading to cases of congenital syphilis and transfusionassociated infection. Latent syphilis is divided into ‘early’ (duration of less than 2 years) and ‘late’ (duration of 2 years or more). Patients with late latent syphilis are immune to reinfection. However, if left untreated, the noninfectious tertiary stage will develop in a third of those infected. The clinical presentation of tertiary syphilis can be wide-ranging and complex, involving invasion of the internal organs, gummatous, and cardiovascular and neurological involvement. Gummas, or destructive lesions, can occur on the skin and are likely to be a result of a host-delayed hypersensitivity response. Gummatous syphilis can involve the organs or their supporting structures and may result in infiltrative or destructive lesions. In turn this can lead to granulomatous lesions or ulcers, including the perforation and collapse of structures such as the palate and nasal septum. Gumma of the tongue may be prone to leucoplakia leading to malignant change. Late neurosyphilis can cause meningovascular syphilis leading to stroke syndromes, parenchymal involvement leading to general paresis, and tabes dorsalis. Cardiovascular syphilis involves the aortic arch and can lead to angina from coronary ostitis, and aortic aneurysms.

The clinical presentation of syphilis can be further complicated by the presence of additional pathologies. For example, syphilitic ulcers can develop into necrotizing fasciitis in the presence of a mixed flora of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria including Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus. This condition, also known as phagedena, has largely disappeared as a result of developments in clinical care and personal hygiene.

An intriguing feature of the natural history of syphilis is that some patients develop severe, destructive complications of the disease whereas others do not. Three major studies have sought to investigate this phenomenon within human populations. The Oslo study conducted by Boeck between 1890 and 1910, with further investigations by Bruusgaard and Gjestland (1929 and 1955), was a prospective study of the progression of untreated primary and secondary syphilis in 1978 patients (Bruusgaard, 1929; Gjestland, 1955). In 1932, a study of the natural history of syphilis was undertaken at the Tuskegee Institute, Tuskegee, Alabama (Rockwell et al., 1964).The study, which involved 412 black men with untreated latent syphilis and 204 uninfected matched controls, was concerned with the assessment of the toxicity of arsenicals and the development of late syphilis. Unfortunately, informed consent was not obtained from the patients and antibiotic therapy was withheld after it became available. On 16 May 1997 the president of the United States apologized to the survivors and their relatives. The Roahn study, conducted between 1917 and 1941 at Yale University, included around 4000 patients and was exclusively confined to observations at autopsy (Roahn, 1947). Although each study used a different methodology, their findings were remarkably similar. Between 15 and 40% of untreated cases develop tertiary syphilis and excess mortality was associated with syphilis infection. More than 60% of untreated patients did not develop late anatomical complications, and for about 20% of the untreated patients syphilis was the cause of death.

Interaction With HIV

Recent outbreaks of syphilis within industrialized countries have shown a high proportion of coinfection between syphilis and HIV, and many countries that have mature heterosexual HIV epidemics also have high rates of coinfection between HIV and syphilis. Like other ulcerative STIs, syphilis promotes the transmission of HIV and both infections can simulate and interact with each other. Studies have indicated that primary and secondary syphilis can increase HIV viral load and lead to a fall in CD4þ T-cell count in HIV-positive patients. Observations from other studies suggest that syphilis may be more severe and may progress more rapidly to neurological and gummatous syphilis in HIV-positive patients, but these findings have not been supported by larger studies. The clinical presentations of syphilis and HIV can also mimic each other. For example, syphilitic chancres can be mistaken for chronic mucocutaneous anogenital herpes in AIDS, while HIV-infected patients may have neurological abnormalities similar to neurosyphilis. HIV infection can lead to larger or more numerous chancres and progress quickly to ulcerating secondary syphilis.

Although serological tests for syphilis generally perform the same way in HIV-positive patients as they do in immunocompetent patients, unpredictable results are sometimes found; for example, a delayed positive serological test may be seen in secondary syphilis.

Congenital Syphilis – ‘The Sins Of The Father Are Visited On The Children’ (Ibsen, Ghosts)

WHO estimates that maternal syphilis is responsible for between 713 600 and 1 575 000 cases of congenital syphilis worldwide, as well as stillbirths or abortions, and low-birth-weight or premature babies (Stoner et al., 2005). Infant mortality can be in excess of 10%. The incidence of congenital syphilis is related to the prevalence of infectious syphilis within the population. Cases of congenital syphilis are costly to health-care systems in high-, middle-, and low-income countries, and, given the low cost of testing, antenatal screening (ANS) is cost-effective even at a prevalence of 0.07%. Congenital syphilis can be prevented through ANS and the treatment structures required for this intervention already exist in many countries. However, although this process is conceptually simple, it relies on the existence and maintenance of well-structured care pathways. In low-income countries case detection and management through ANS, although difficult due to operational constraints, can result in avoidable perinatal morbidity.

Three of the Millennium Development Goals adopted by the members of the United Nations are related to maternal and child health. These are reducing child mortality, improving maternal health, and combating HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases. The WHO aims to reduce maternal morbidity, fetal loss, and neonatal mortality and morbidity due to syphilis and is starting a global effort to eliminate congenital syphilis. The standard for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of syphilis is as follows.

All pregnant women should be screened for syphilis at the first antenatal visit within the first trimester and again in late pregnancy. At delivery, women who do not have test results should be tested/re-tested. Women testing positive should be treated and informed of the importance of being tested for HIV infection. Their partners should also be treated and plans should be made to treat their infants at birth. (WHO, 2006b)

By 2009, the WHO seeks to reduce congenital syphilis incidence by 90% in four countries, and eliminate congenital syphilis from Europe by 2015. Essentially the elimination strategy consists of three steps, universal access to professional antenatal care, access to care early in pregnancy, and on-site testing and treatment. However, there are a number of obstacles to the presentation and detection of infection in pregnant women, including: the detection of infection in reproductive age women, the availability and ease of access to ANS, access to accurate rapid testing facilities, the availability of appropriate treatment, screening in third trimester and at delivery, and sufficient staffing and continuity in staffing. These problems cut across health-care systems and vary among countries. For example, in Atlanta, Georgia (USA), such problems include: limited access to antenatal care, limited access to testing and treatment facilities, high levels of treatment failure, and high levels of reinfection (Warner et al., 2001). In contrast, in sub-Saharan Africa, obstacles include: high cost of treatment and testing, inadequate political backing, social/cultural resistance, and insufficient qualified staff (Gloyd et al., 2001). The high priority given to the role of antenatal care in the prevention of vertical transmission of HIV provides a focus for the prevention of congenital syphilis. Health services need to concentrate on how ANS can be undertaken more efficiently, and which other clinical settings should be used for screening. However, it should also be remembered that although the incidence of congenital syphilis can be reduced by the consolidation of existing interventions, elimination relies on parallel strategies for syphilis prevention and control within the adult population.

Although the vast majority of congenital syphilis cases are seen in developing countries, congenital syphilis also occurs in affluent nations. The evolving European syphilis epidemic has resulted in an increased incidence of infectious (primary, secondary, and early latent) syphilis in reproductive age women and congenital syphilis.

In the UK, the emergence of infectious syphilis in the late 1990s was characterized by a series of outbreaks and foci (Simms et al., 2005). Although the main feature of the epidemic is the rapid increase in cases seen among men who have sex with men, cases reported among heterosexual men and women are also increasing.

The WHO suggests that incidence of congenital syphilis, perinatal and neonatal mortality due to congenital syphilis, and stillbirth rate could be used as outcome measures with which to assess the impact of screening for congenital syphilis. However, measuring congenital syphilis incidence is difficult despite the comprehensive surveillance data sets available within developed nations such as the UK. Diagnoses are recorded in statistical returns from sexually transmitted disease clinics, but these are likely to be incomplete as cases will also be managed in pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology. A nationally coordinated study that investigated maternal and congenital infection diagnosed by pediatricians and sexual health consultants was carried out between 1994 and 1997, a time when new diagnoses among women were at a much lower level (Hurtig et al., 1998). Nine presumptive and eight possible cases were reported but none were confirmed.

In recent years about six congenital cases per annum have been reported by sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics. If it is assumed that this represents 30 to 50% of actual cases, then approximately 10 to 20 cases would be expected annually. Reports of two cases of congenital syphilis have been published. In both cases infection was acquired in the third trimester, both were connected with commercial sex work and drug users, and one had not attended antenatal care. Current UK management guidelines suggest that all pregnant women should be tested in the first trimester; for those patients in whom infection is identified, testing in the third trimester is also recommended. However, the identification and management of infection in women who are at high risk of infection and yet are marginalized in society is a challenging prospect as these women are unlikely to come into contact with health-care services until delivery.

Intervention

In 1497 residents of Edinburgh, Scotland, who were infected with syphilis were banished to the island of Inchkeith on pain of branding. Such extreme attempts at infection control were once common and indicate how syphilis has challenged established public health strategies for individual-, partnership-, and population-based interventions. The correct, consistent use of condoms should prevent the transmission of infection during sexual intercourse. The use of both male and female condoms has been shown to reduce the transmission of syphilis in men and women and is an essential part of STI control programs (Holmes et al., 2004). Other individual-based interventions, such as male circumcision and the use of microbicide preparations, do not reduce the transmission of syphilis.

Partnership-based interventions seek to interrupt transmission between sexual partners, either by reducing the risk of transmission or by preventing reinfection. In cases of syphilis, partnership-based interventions are centered around partner notification and antenatal screening (see the section, Congenital Syphilis). Partner notification seeks to interrupt the onward transmission of infection and prevent reinfection. Sufficient partners have to be treated to interrupt transmission within the population. A variety of methods is used including patient referral (patient informs partner/s), provider referral (health professional informs partner/s), and conditional referral (health-care professional informs partner/s after an agreed period) (Low et al., 2004). From a public health perspective partner notification is a difficult intervention to undertake successfully, particularly if the majority of sexual contacts are anonymous, as has been the case in the recent syphilis outbreaks within industrialized countries. And from the patient’s viewpoint, the stigma, blame, physical violence, and relationship breakdown that may accompany this intervention can make partner notification very difficult.

The Vancouver mass treatment intervention was a population-based intervention that aimed to eliminate a long-running outbreak of syphilis in Vancouver, British Columbia (Canada), in early 2000 (Reckart et al., 2003). Following several years of very low reported rates of infectious syphilis (less than 0.5 per 100 000 population), there was a marked increase in the number of reported cases from mid-1997 onward centered on a geographically localized outbreak in Vancouver’s disadvantaged downtown eastside area (Patrick et al., 2002). Rates of infection had reached 126 per 100 000 in 1999, and, of the 277 reported cases, 65% were among people who had contact with a potential source of their infection from the local area. The outbreak was spread mainly through heterosexual contact, with 42% of patients associated with the sex industry (18% of whom were sex workers and 24% clients) (Patrick et al., 2002). Only 6% of cases were in MSM. A combination of individual and partnership-based interventions including condom distribution, partner notification, and public education had failed to control the outbreak, so a targeted mass treatment initiative was implemented in January 2000. The strategy was adopted because of the geographical concentration of the population at risk and the availability of a single-dose oral treatment, 1.8 g azithromycin (Hook et al., 1999). Sex workers, their clients, and people reporting recent (unprotected) casual sexual contact, were recruited. Treatment doses and information were given to participants to pass on to other sexual and social contacts (termed ‘secondary carry’). The intervention reached 2981 (8.1%) residents aged 15 to 49 years in the downtown eastside area and 1055 of the estimated 1300 to 2600 commercial sex workers in Vancouver. There was a significant fall in the mean number of reported syphilis cases from February to July 2000 (monthly mean 6.7 compared with 10.2 pre-intervention), but by September 2000 rates had returned to pre-intervention levels, and by 2001 the rate of reporting was higher than in 1999. Two previous, smaller mass treatment interventions in North America also showed successful results after 6 months of follow-up (Hibbs and Gunn, 1991; Jaffe et al., 1979). However, such short-term decreases in syphilis incidence may not be sustainable, and may even have negative consequences on post-intervention syphilis incidence rates. The lack of a sustained effect is likely due to the failure to reach and treat high enough proportions of the marginalized and inaccessible sections of the target population (Reckart et al., 2003). Effectively, targeted mass treatment may have increased the pool of susceptible, high-risk individuals who are subsequently exposed to infectious syphilis by those who were not reached by the intervention. Treatment failure may also have reduced the impact of the intervention (CDC, 2004; Stapleton et al., 1985).

Nevertheless, the Vancouver study is an example of the use of community and peer outreach as a means of accessing marginalized, ‘hard to reach’ groups at high risk of syphilis infection. Experience from this intervention is not applicable to developing countries, particularly in subSaharan Africa, where high HIV and STI incidence rates in the core group of sex workers, coupled with lack of access to appropriate health care and STI diagnostic facilities, may in some contexts justify administration of rounds of mass treatment for STIs at regular intervals, so-called periodic presumptive treatment. Such an approach was implemented in a South African mining community, where a directly observed 1g dose of azithromycin was given every month to sex workers attending a mobile clinic. This resulted in significant declines in the prevalence of C. trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and clinically observed genital ulcer disease in sex workers. Decreased rates of symptomatic STIs were also observed in the clientgroup of miners in the intervention area (Steen et al., 2000).

Syndromic management remains the main intervention recommended by the WHO for the prevention of STIs in resource-poor settings where diagnostic facilities are not available. This individual-based intervention involves health-care workers matching clinical signs and symptoms against predefined flow charts that detail clinical presentation and associated interventions, such as partner notification and condom distribution, and appropriate medical intervention including therapy. Prospective studies have suggested that syndromic management can be effective in the control of syphilis (Pettifor et al., 2000).

The recent syphilis outbreaks in industrialized countries have challenged traditional public health approaches to syphilis control as a substantial number of cases were unable or unwilling to name their sexual contacts. Innovative approaches including targeted peer outreach among social networks combined with noninvasive sampling techniques, such as saliva testing, have been used to aid case detection and increase treatment of infected individuals. In particular, local multisector intervention initiatives that specifically target those at high risk of acquiring or transmitting syphilis have proved to be a valuable addition to national control efforts (Simms et al., 2005).

Conclusion

The WHO describes syphilis as ‘the classic example of a STI that can be successfully controlled by public health measures due to the availability of a highly sensitive diagnostic test and a highly effective and affordable treatment’ (WHO, 2006a). Although this is true, syphilis remains a worldwide public health problem in 2008, and the persistence of this preventable disease reflects a failure of syphilis control programs, as well as a lack of political will. Social and behavioral studies are vital to our understanding of syphilis epidemiology and the public health response to these epidemics. In particular, the effectiveness of intervention strategies that target those at high risk of acquiring or transmitting syphilis, including group and peer-based programs, needs to be evaluated, optimized, and extended.

Bibliography:

- Anderson RM, May RM, and Anderson B (1992) Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- BASHH (2006) Clinical Effectiveness Group. UK National Guidelines on the Management of Early Syphilis. http://www.bashh.org/ guidelines.

- Bruusgaard E (1929) Ober das schicksal der nicht specifisch behandelten leuktiker. Archives of Dermatology and Syphilis 157: 309.

- CDC (2004) Azithromycin treatment failures in syphilis infections – San Francisco, California, 2002–2003. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 53(9): 197–198.

- Gjestland T (1955) The Oslo study of untreated syphilis: An epidemiologic investigation of the natural course of syphilitic infection based on a re-study of the Boeck-Bruusgaard material. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 35(supplement): 34.

- Gloyd S, Chai S, and Mercer MA (2001) Antenatal syphilis in subSaharan Africa: Missed opportunities for mortality reduction. Health Policy and Planning 16: 29–34.

- Grassly NC, Fraser C, and Garnett GP (2005) Host immunity and synchronised epidemics of syphilis across the United States. Nature 433: 417–421.

- Grenfell BT, Bjornstad ON, and Kappery J (2001) Travelling waves and spatial hierarchies in measles epidemics. Nature 414: 716–723.

- Hibbs JR and Gunn RA (1991) Public health intervention in a cocaine- related syphilis outbreak. American Journal of Public Health 81: 1259–1262.

- Holmes KK, Levine R, and Weaver M (2004) Effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted infections. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82: 454–461.

- Hook EW 3rd, Stephens J, and Ennis DM (1999) Azithromycin compared with penicillin G benzathine for treatment of incubating syphilis. Annals of Internal Medicine 131: 434–437.

- Hurtig A-K, Nicoll A, Carne C, et al. (1998) Syphilis in pregnant women and their children in the United Kingdom: Results from national clinician reporting surveys 1994–7. British Medical Journal 317: 1617–1619.

- Idsoe O, Guthe T, and Willcox RR (1972) Penicillin in the treatment of syphilis: The experience of three decades. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 47: 1–68.

- Jaffe HW, Rice DT, Voigt R, Fowler J, and St. John RK (1979) Selective mass treatment in a venereal disease control program. American Journal of Public Health 69: 1181–1182.

- Lewis DA and Young H (2006) Syphilis. Sexually Transmitted Infections 82(4): 13–15.

- Low N, Welch J, and Radcliffe K (2004) Developing national outcome standards for the management of gonorrhoea and genital chlamydia in genitourinary medicine clinics. Sexually Transmitted Infections 80: 223–229.

- Morton RS (1990) Syphilis in art: An entertainment in four parts. Parts 1–4. Genitourinary Medicine 66: 33–40, 112–123, 208–221, 280–294.

- Oriel JD (1994) The Scars of Venus. London: Springer-Verlag. Patrick DM, Rekart ML, Jolly A, et al. (2002) Heterosexual outbreak of infectious syphilis: Epidemiological and ethnographical analysis and implications for control. Sexually Transmitted Infections 78 (supplement 1): 164–169.

- Peeling RW (2006) Testing for sexually transmitted infections: A brave new world? Sexually Transmitted Infections 82: 425–430.

- Pettifor A, Walsh J, Wilkins V, and Raghunathan P (2000) How effective is syndromic management of STDs? A review of current methods. Sexually Transmitted Infections 27: 371–385.

- Reckart ML, Patrick DM, Chakraborty B, et al. (2003) Targeted mass treatment for syphilis with oral azithromycin. Letter. The Lancet 361: 313–314.

- Roahn PD (1947) U.S. Public Health Service, Venereal Disease Division. Autopsy Studies in Syphilis 21(supplement).

- Rockwell DH, Yobs AR, and Moore MB (1964) The Tuskeegee study of untreated syphilis. The 30th year of observation. Archives of Internal Medicine 114: 792–798.

- Simms I, Fenton KA, Ashton M, et al. (2005) The re-emergence of syphilis in the UK: The new epidemic phases. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 32: 220–226.

- Singh AE and Romanowski B (1999) Syphilis: Review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clinical Microbiological Reviews 12(2): 187–209.

- Stapleton JT, Stamm LV, and Bassford PJ (1985) Potential for development of antibiotic resistance in pathogenic treponemes. Review of Infectious Diseases 7(supplement 2): S314–S317.

- Steen R, Vuylsteke B, DeCoito T, et al. (2000) Evidence of declining STD prevalence in a South African mining community following a core-group intervention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 27: 9–11.

- Stoner BP, Schmid G, Guraiib M, Adam T, and Broutet N (2005) Use of Maternal Syphilis Seroprevalence Data to Estimate the Global Morbidity of Congenital Syphilis. Bangkok: IUSTI World Congress.

- Warner L, Rochat RW, Fichtner RR, Stoll BJ, Nathan L, and Toomey KE (2001) Missed opportunities for congenital syphilis prevention in an urban south eastern hospital. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 28: 92–98.

- WHO (2006a) Global Prevalence and Incidence of Selected Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections: Overview and Estimates. http:// www.who.int/hiv/pub/sti/who_hiv_aids_2001.02.pdf (accessed November 2007).

- WHO (2006b) Standards for Maternal and Neonatal Care 1.3: Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of Syphilis. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Holmes KK (ed.) (1990) Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill Information Services.

- http://www.cdc.gov – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- http://www.hpa.org.uk – Health Protection Agency (HPA).

- http://www.nih.com – National Institutes of Health (NIH).

- http://www.who.int – World Health Organization (WHO).

- http://www.who.int/std_diagnostics – World Health Organization (WHO) Sexually Transmitted Diseases Diagnostics Initiative.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.