This sample Trauma and Mental Disorders Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

In recent decades, much attention has been given to the impact of psychological trauma on mental health. Trauma is distinguished from major stresses such as marital separation, financial hardship, and work problems in that it involves a fundamental threat to the life or integrity of individuals or those close to them. The category of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has tended to dominate the field since its introduction in 1980 into the American Psychiatric Association classification system’s third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. The present article provides an overview of PTSD and its causes, outcomes, and treatment. We will also examine other psychological outcomes of trauma, consider psychological responses to gross human-instigated abuses, and explore issues relevant to a public health response to mass disasters.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Diagnosing PTSD

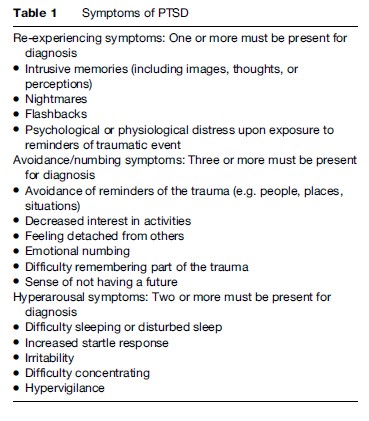

Four major criteria are applied to diagnose PTSD (DSMIV; APA, 1994). Criterion A requires exposure to an environmental event that threatens the safety or integrity of the self or someone else. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. (DSM-IV) requires that, in addition to the environmental threat, the person responds in a subjective manner with feelings of fear, horror, and/or helplessness. The B criterion involves reliving the traumatic experience in the form of flashbacks or nightmares. The memories are vivid, intrude unbidden into consciousness, and can manifest in multiple sensory modalities. In extreme situations, the survivor may dissociate, that is feel and act as if he or she is detached from the immediate environment and is actually reliving the traumatic experience in the present, albeit in a fragmented and chaotic manner. The re-experiencing phenomena are widely regarded as being the defining features of PTSD, setting the disorder apart from other anxiety and stress related conditions. In contrast, the remaining two domains of PTSD, avoidance and numbing (Criterion C), and arousal (Criterion D), have features in common with other anxiety disorders, in that they broadly represent defensive responses to extreme fear. Criterion C includes avoidance of thoughts, activities, or places that remind the survivor of the initial trauma. These situations trigger re-experiencing symptoms. Someone who was robbed at a bank not only avoids the specific site where the hold-up occurred, but through conditioning, cues are generalized to include all banks or reminders, for example, advertising on television. In addition, survivors may feel numb in their emotional responses, so that family and friends describe them as being uncharacteristically remote, unresponsive, and unfeeling. Survivors may become socially isolated, preferring their own company to normal interpersonal interactions. The final symptom domain (Criterion D) of PTSD involves psychophysiologic arousal. Symptoms include a rapid heart rate (tachycardia), palpitations, sweating, shakiness, and other somatic experiences. Survivors experience marked startle reactions, insomnia, poor concentration, and difficulties with memory. They can be irritable and are quickly moved to angry outbursts, a response pattern that causes difficulties in family and social interactions.

To make a diagnosis of PTSD, a sufficient number of symptoms from each domain must be present for at least 1 month and the disorder must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning. In its severe form, PTSD can lead to major dysfunction in areas of work, family, and social relationships (Table 1).

Triggers And Course Of PTSD

A wide range of traumas can lead to PTSD, including accidents, assault, natural disasters, exposure to warfare and other forms of conflict, as well as gross abuses such as rape, child sexual abuse, torture, and other forms of human-instigated violence. The course of PTSD is somewhat variable. Distress in the acute phase after trauma is common. Persons who have severe PTSD symptoms at this stage together with marked dissociative symptoms qualify for a diagnosis of acute stress disorder (APA, 1994). Nevertheless, in most trauma-affected populations, only a minority go on to develop chronic PTSD. The percentage varies according to the type, severity, and repetitiveness of the trauma. Women and those with a past psychiatric history or with previous exposure to trauma are more vulnerable. Populations exposed to ongoing stresses or danger, for example, people living in dangerous or unsettled refugee camps, tend to experience persistently high rates of PTSD. Nevertheless, following the accidental traumas of everyday life (injuries, motor vehicle accidents, and the like), only a minority of survivors tend to develop chronic PTSD, in the range of 10–15% (McNally et al., 2003). At a population level, the National Comorbidity Study (NCS) conducted in the United States indicated that while 60.7% of men and 51.2% of women are exposed to trauma at some time during their lives, only 8.2% of men and 20.4% of women develop PTSD (Kessler et al., 1995). Survivors of extreme human-instigated trauma such as rape, torture, and exposure to other gross human rights violations tend to have higher rates of PTSD, ranging from 20 to 40% (e.g., Basoglu et al., 1994; de Jong et al., 2001). Hence, except for the most severe forms of trauma, most survivors show high levels of resilience in the posttraumatic phase, recovering from acute feelings of distress.

Predicting those at risk of PTSD based on acute posttraumatic symptoms remains problematic. Emerging evidence indicates that a small group of survivors with very high levels of distress, particularly manifested as repetitive intrusions and heightened arousal, are at great risk of experiencing persisting PTSD (Silove, 2007). The problem remains, however, that another subgroup with intermediate levels of acute symptoms progresses to become full cases of PTSD at a later time. Hence, from a public health perspective, current methods do not allow accurate identification of the whole group at risk of future PTSD, for example, among injury survivors admitted to hospital. Nevertheless, from a service perspective, there is sufficient evidence to warrant identifying the highly symptomatic group in the early posttraumatic phase and to offer them evidence-based interventions that have been shown to prevent the later development of chronic PTSD (McNally et al., 2003).

Causes Of PTSD

Although there is ample evidence that PTSD is triggered by life-threatening events, the underlying pathogenesis of the disorder remains unclear. At a biological level, several factors have been implicated, including abnormalities in stress hormone responses mediated via the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Some brain imaging studies have shown that PTSD sufferers have a reduced hippocampal volume, which may be relevant since that brain center is pivotal in contextualizing trauma memories (e.g., Bremner et al., 1997). The amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex have also been implicated, since these centers mediate the learned fear response, mobilizing pathways that activate flight and fight reactions. The prevailing neural network theory of PTSD suggests that there is inadequate regulation of the medial prefrontal cortex of amygdala-generated fear responses, thereby allowing environmental triggers to maintain fear reactions (Rauch et al., 2006). Cognitive theories of PTSD suggest that faulty thought processes or attributions lead to persistence of the learned fear response (Ehlers and Clark, 2000). In other words, expecting catastrophic outcomes perpetuates the PTSD reaction. An evolutionary perspective (Silove, 1998) suggests that the re-experiencing of trauma memories ensures that survivors mobilize defensive responses if exposed to further environmental cues signaling the return of the danger. In some survivors, medial prefrontal mechanisms fail to exert adequate control on this amygdala-mediated normative survival response so that memory rehearsal continues unchecked.

Treatment Of PTSD

In Western countries, although many different types of therapy are offered, research has identified two specific domains of treatment (psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy) that are effective for PTSD. All interventions need to be guided by some key principles. These include sensitive engagement with patients in a therapeutic relationship that allays anxiety, promotes trust and dignity, and creates a setting of safety and security. Providing information about the disorder and its causes, and where appropriate, educating the family about the approach to treating the condition are vital. General lifestyle interventions are important, including attention to ongoing stresses, work, family life, leisure activities, and legal and compensation issues where relevant. The specific form of psychotherapy that has most scientific support is cognitive behavioral therapy. The therapy should be provided by trained professionals. In brief, the key interventions include anxiety reduction (relaxation exercises, attention to panic symptoms, for example, by using slow breathing exercises), cognitive restructuring (challenging negative thoughts that perpetuate high levels of anxiety), and exposure therapy where the survivor is guided systematically in imagination through the trauma experience over a number of sessions. Pharmacotherapy involves the use of the newer antidepressants that enhance the action of serotonin and/or norepinephrine. Typical medications include sertraline, paroxetine, and mirtazapine. In some settings, the older tricyclic antidepressants are used, but close supervision is needed because of potential toxic effects. Other medications such as mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and sedatives are used, but there is insufficient evidence to recommend these treatments as first-line interventions. All medications can cause side effects and have risks, for example in overdose. The indiscriminate, long-term use of the benzodiazepine tranquilizer class of drugs such as diazepam should be avoided because of dependency, the risk that the dose will be escalated, and withdrawal effects.

Other Psychiatric Disorders Arising From Trauma

PTSD occurs in conjunction with other psychological disorders in over 70% of cases (Kessler et al., 1995). A review of studies has shown that depression is the second most common psychological disorder in survivors of disasters followed by other forms of anxiety (Norris et al., 2002). Other disorders also are common. After the Oklahoma City bombing, 34% of survivors experienced PTSD, 22% depression, 7% panic disorder, 4% generalized anxiety disorder, 9% alcohol use disorder, and 2% drug use disorder; overall, 30% of people had a psychiatric disorder other than PTSD (North et al., 1999). The rates for most of these disorders exceed those in the general population (Brown et al., 2000), indicating that trauma is a significant contributor to the onset of these problems. Traumatic or complicated grief is another response that has only received attention more recently. There is a risk that it will be confused with PTSD since both groups experience intrusive memories. Those with grief, however, have vivid memories of the deceased or missing person, which, although distressing, do not generate a sense of threat in the survivor.

Psychological Responses To Extreme Abuse And Persecution

Survivors of severe abuse such as torture, sexual abuse, and related forms of intentional human violence manifest a range of psychological reactions that are not fully incorporated into the criteria for PTSD. In the past, these reactions were identified according to the cause, for example, the torture or concentration camp syndromes. More recently, more general terms used include complex PTSD or disorders of extreme stress not otherwise specified (referred to but not fully adopted by DSM-IV) and enduring personality change after catastrophic events (EPCACE), a category included for the first time in the International Classification of Diseases Edition 10 (ICD-10). In all these formulations, anger, mistrust, and hostility are prominent, in recognition that these reactions are closely tied to feelings of having one’s rights and dignity violated (Silove, 1996). Other features observed include guilt and shame, a tendency to somatic complaints, extreme forms of dissociation, feelings of pervasive isolation and alienation, and unrelenting hopelessness. There are similarities between these descriptions and the criteria for diagnosing borderline personality disorder, a condition linked to early childhood abuse. Further scientific evidence is needed, however, to confirm the specific features (beyond PTSD) that characterize the essential features of these more complex reactions to intentional human abuse.

The following case description illustrates complex PTSD.

An elderly Cambodian refugee who had lived in Australia for 20 years was referred to a trauma treatment service. His family described him as withdrawn, uncommunicative, lost in his own world, irritable and angry at times, and unable to enjoy any aspect of his life. These characteristics had been present for many years but he had become noticeably more depressed and hopeless in recent times. He was interviewed with an interpreter but even so remained monosyllabic through the first few sessions. He did reveal sufficient information to allow PTSD symptoms to be identified and an additional diagnosis of major depression to be made and he was prescribed antidepressants at low dose. He regarded his problem as arising from his karma and he was skeptical that any treatment could work. Over the next 2 months, he appeared to become more trusting of the therapeutic environment. He revealed that during the Pol Pot times (the Khmer Rouge autogenocide of 1975–79), he and his family were subjected to slave labor. He was beaten and tortured on several occasions because he was a member of the professional elite prior to the revolution. On one occasion, he was forced to torture his brother who was accused of being a traitor. He became enraged when he thought of the injustices he had suffered but also felt guilt-stricken and ashamed because of his actions. Psychotherapy focused on dealing with his PTSD symptoms using cognitive-behavioral methods and in addition exploring cautiously and gradually his sense of guilt and shame. He came to realize that he was in a situation of forced choices, that is, he had no control over his actions during his period of captivity. His depression and PTSD symptoms improved and he became more actively engaged in pursuing his Buddhist faith by attending the temple. Improvements overall were modest, however, and the family reported that he never returned fully to his old self preceding the trauma.

Mass Impacts Of Trauma

A large proportion of the world’s population has been exposed to trauma, particularly taking into account populations experiencing mass violence such as warfare, persecution, and displacement; societies exposed to terrorist attacks; and regions that experience natural disasters such as tsunamis, earthquakes, floods, fires, and hurricanes.

Limited resources and professional skills in low and middle-income countries make it impossible for all survivors to obtain high-quality psychological care. Individual or small group psychological debriefing, where survivors are encouraged to explore their reactions to trauma in the immediate aftermath of disasters, is neither feasible nor effective and can be damaging to those with high levels of arousal. The majority of survivors have the capacity to recover spontaneously and the speed and extent to which that occurs depends largely on the effectiveness of the emergency humanitarian response and the subsequent reconstruction process. The ADAPT model (Adaptation & Development After Persecution and Trauma) (Silove and Steel, 2006) identifies five major psychosocial domains that are threatened by disasters and that, if repaired effectively, support posttraumatic recovery at an individual and population level. These domains or pillars include safety and security; bonds and networks; systems of justice; roles and identities; and institutions and practices that support a sense of meaning and coherence, including culture, religion, and political participation. It is argued that where the aid and reconstruction process assists in rebuilding these psychosocial pillars, survivor populations have a greater capacity to mobilize their own resources to hasten recovery. Conversely, in settings of effective social recovery there should be lower rates of persisting traumatic stress reactions over time. For example, Vietnamese refugees resettled as permanent residents in conditions of security in Australia over 11 years were shown to have low prevalence rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety (Steel et al., 2002). On arrival in Australia, the Vietnamese were given secure residency status, access to education and work opportunities, and support to sponsor families to join them. They have been free to maintain their culture and to pursue their religious practices. In contrast, other displaced populations exposed to similar traumas in their home countries who continue to live under conditions of insecurity, for example, with temporary protection visas, continue to manifest high levels of PTSD and related mood disturbances (Steel et al., 2006).

It seems likely that aid programs that effectively repair the psychosocial pillars identified by the ADAPT model will achieve the optimal outcomes in terms of population recovery from traumatic stress. From a mental health perspective, this means that the focus moves away from direct psychological debriefing of individual survivors toward what is now referred to as a program of community-wide psychological first aid. The aim is to alleviate acute distress by fostering a calm, safe, and supportive environment, to connect people with family, communities, and support agencies, and to promote self-efficacy, hope, and empowerment in those affected by the trauma. This can be achieved by helping individuals and families to meet their basic needs (food and water, shelter, health care), providing accurate information and practical assistance, helping families to reassemble or stay together, ensuring that people are dealt with in a dignified and nondiscriminating way, giving survivors an active role in planning and implementing the recovery process, and targeting emotional and psychiatric support more accurately to those in special need.

The United Nations Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2007) has developed guidelines to assist humanitarian agencies in planning and implementing psychosocial aid programs in the aftermath of mass trauma. Guidelines are presented in the form of a matrix of action, providing suggested responses for each stage of a disaster. Action sheets offer a step-by-step description of key initiatives. Also listed are available resources, examples of programs from previous emergency situations, and suggestions for interorganizational coordination. Major topic areas include mental health and psychosocial assessments, orientation and training of aid workers, and protecting individuals under threat.

Whereas a population-wide approach is pivotal to an effective mental health response to disasters, a minority of survivors will need direct mental health services because their level of distress is so severe that it prevents them or their families from coping with the demands of the posttraumatic environment. Communities readily identify these persons by their behavioral disturbances (Silove et al., 2004). That heterogeneous group includes people with severe and disabling posttraumatic reactions and others with preexisting mental and neuropsychiatric disorders such as psychosis and epilepsy. If well designed and implemented, community-based emergency mental health clinics can provide critical care to these patients and their families. In developing countries, these clinics can be the forerunner of and shape future service development as the society enters the post-disaster development phase.

Conclusions

Exposure to psychological trauma is extensive around the globe. Most persons and their communities recover from the initial distress that such experiences cause, but a minority continue to suffer a range of psychological problems including PTSD. There is no one intervention that addresses all the needs of survivors and their communities. In settings of mass trauma, particularly in countries with low resources, the emphasis should be on rebuilding the social pillars that assist survivor communities to reestablish their lives and hence achieve psychological equilibrium. Early psychological debriefing for all survivors is neither necessary nor feasible in settings of large-scale disasters. Nevertheless, there will always be a minority of survivors who manifest severe and disabling traumatic stress reactions and it is vital that they and others with severe psychiatric disorders are identified and provided with best practice interventions to limit chronic disability. Evidence is accruing that cognitive-behavioral therapy adapted to culture and context is the treatment of choice for individuals with established PTSD. All interventions, whether focused on the individual or on whole populations, need to address the challenges of being a survivor struggling to overcome the impact of trauma. Practitioners need to create a context of trust, respect, and safety, encouraging survivors to play an active role in their own recovery.

Bibliography:

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Basoglu M, Paker M, Paker O, et al. (1994) Psychological effects of torture: A comparison of tortured with nontortured political activitists in Turkey. American Journal of Psychiatry 151: 76–81.

- Bremner JD, Randall P, Vermetten E, et al. (1997) Magnetic resonance imaging-based measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood physical and sexual abuse – A preliminary report. Biological Psychiatry 41: 23–32.

- Brown ES, Fulton MK, Wilkeson A, and Petty F (2000) The psychiatric sequelae of civilian trauma. Comprehensive Psychiatry 41: 19–23.

- de Jong JT, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M, et al. (2001) Lifetime events and posttraumatic stress disorder in four postconflict settings. Journal of the American Medical Association 286: 555–562.

- Ehlers A and Clark DM (2000) A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy 38: 319–345.

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) (2007) IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Geneva, Switzerland: IASC.

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Hughes M, and Nelson CB (1995) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52: 1048–1060.

- McNally RJ, Bryant RA, and Ehlers A (2003) Psychological debriefing and its alternatives: A critique of early intervention for trauma survivors. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 4: 45–79.

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, et al. (2002) 60 000 disaster victims speak: Part 1. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry 65(3): 207–239.

- North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, et al. (1999) Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. Journal of the American Medical Association 285: 755–762.

- Rauch SL, Shin LM, and Phelps EA (2006) Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and extinction: Human neuroimaging research – Past, present, and future. Biological Psychiatry 60: 376–382.

- Silove D (1996) Torture and refugee trauma: Implications for nosology and treatment of posttraumatic syndromes. Mak FL and Nadelson CC (eds.) International Review of Psychiatry, vol. 2, pp. 211–232. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association

- Silove D (1998) Is posttraumatic stress disorder an overlearned survival response? An evolutionary-learning hypothesis. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes 61: 181–190.

- Silove D (2007) Adaptation, ecosocial safety signals and the trajectory of PTSD. In: Kirwayer LJ, Lemelson R and Barad M (eds.) Understanding Trauma: Integrating Biological, Clinical and Cultural Perspectives, pp. 242–258. New York: Cambridge University Press

- Silove D and Steel Z (2006) Understanding community psychosocial needs after disasters: Implications for mental health services. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine 52: 121–125.

- Silove D, Manicavasagar V, Baker K, et al. (2004) Indices of social risk among first attenders of an emergency mental health service in postconflict East Timor: An exploratory investigation. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 38: 929–932.

- Steel Z, Silove D, Phan T, and Bauman A (2002) Long-term effect of psychological trauma on the mental health of Vietnamese refugees resettled in Australia: A population-based study. Lancet 360: 1056–1062.

- Steel Z, Silove D, Brooks R, et al. (2006) Impact of immigration detention and temporary protection on the mental health of refugees. British Journal of Psychiatry 188: 58–64.

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, and Valentine JD (2000) Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68: 748–766.

- Bryant RA and Friedman M (2001) Medication and non-medication treatments of posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 14: 119–123.

- Charney DS, Deutch AY, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, and Davis M (1993) Psychobiologic mechanisms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 50: 294–305.

- Davidson RJ and Foa EB (eds.) (1993) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Foa EB and Meadows EA (1997) Psychosocial treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: A critical review. Annual Review of Psychology 48: 449–480.

- Foa EB, Keane TM, and Friedman MJ (eds.) (2000) Effective Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. New York: Guilford Press.

- Litz BT, Gray M, and Bryant RA (2002) Early intervention for trauma: Current status and future directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 9: 112–134.

- McNally RJ (2003) Remembering Trauma. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Yehuda R (ed.) (1999) Risk Factors for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- http://www.ncptsd.va.gov/ – National Center for PTSD.

- http://www.nice.org.uk/ – NICE Treatment Guidelines for PTSD.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.