This sample Mental Disorders Associated with Aging Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Dementia

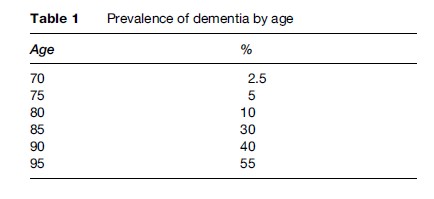

Dementia is strongly associated with increasing age. It is very rare among individuals below the age of 65 years, while the prevalence is more than 50% among individuals above age 90 (Table 1). Dementia is a syndrome characterized by a decline in memory and other intellectual functions (i.e., orientation, visuospatial abilities, executive functions, language, and thinking), often accompanied by changes in personality and emotions. The disturbance is a decline from a previous higher level and gives rise to difficulties in everyday life. Around 70 disorders have been associated with a dementia syndrome, the most common being Alzheimer disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD). A combination of these disorders (mixed dementia) may be most common. Other psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis, are very common among demented individuals.

Early criteria for dementia were based on the presence of memory dysfunction and disorientation for time and place. The modern concept of dementia emphasizes that dementia is a global decline that affects intellectual functions beyond memory. The most often used definitions of dementia in scientific studies are those released by the American Psychiatric Association; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd revised version (DSMIII-R; American Psychiatric Association, 1987), and the fourth version (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), and the classification by the World Health Organization, International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 10th version (ICD-10; World Health Organization, 1992). DSM-III-R is most commonly used in epidemiological studies since its criteria were current when several large population studies started in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Both DSM and ICD criteria regard memory disturbance as mandatory for a diagnosis, but also require the presence of other disturbances of cognitive functions. ICD-10 also requires changes in personality. These diagnostic systems have been questioned because they are based on the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), where memory disturbance occurs early. Dementia disorders with more circumscribed symptoms, focal signs or an atypical course may therefore not be classified as dementia, e.g., some vascular dementias or frontal lobe dementia. The concept vascular cognitive impairment was introduced to capture the more complex pattern seen in individuals with intellectual disturbances related to cerebrovascular diseases.

Alzheimer’s Disease

AD is characterized by an insidious onset with slowly progressive impairments in intellectual functions, typically presenting with memory problems, and changes in personality and emotions. Individuals developing AD, and to some extent VaD, show very mild symptoms regarding memory, executive functions, language, and personality decades before the disease can be diagnosed. These symptoms probably reflect incipient brain pathology. However, at this stage there is a large overlap with normal aging. This dimensional rather than categorical character makes prodromal symptoms of dementia difficult to distinguish from normal aging. The concept of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was introduced during the early 1990s to capture individuals with prodromal AD. The concept of MCI is uncertain and the prevalence figures vary widely. Besides objective measures of intellectual dysfunction, it also often requires self-reported problems with memory, which means that a large group of elderly persons with intellectual dysfunction will not be classified as MCI. MCI is often divided into three groups based on the symptom pattern, amnestic MCI (only memory impairment), multiple domains slightly impaired, and single non-memory domain impairment. It is reported that 15–20% of patients with MCI develop dementia each year. Other names for this state are age-associated memory impairment (AAMI) and cognitive impairment not dementia (CIND).

The neuropathology of AD includes extensive neuronal loss and deposition of extracellular senile plaques (SP) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in the hippocampus and the frontal and temporal cortex, while the motor cortex is spared. The b-amyloid protein is one of the main components of the SP and is also diffusely deposited in the brains of AD patients. Amyloid deposition is often regarded to be central in the pathogenesis of AD, starting a cascade that results in neuronal destruction (the amyloid cascade hypothesis). NFTs are intracytoplasmatic changes, composed of paired helical filaments (PHF), which are proteinaceous filaments twisted around each other in a helical manner. PHFs contain an abnormally hyperphosphorylated form of tau protein. However, extensive brain deposition of b-amyloid and NFTs is often found in normal aging, and in several other brain disorders. Other changes in patients with AD include synaptic loss in the hippocampus and in several cortical regions, and disturbances in the cholinergic, serotonergic, noradrenergic, dopaminergic, glutaminergic, and neuropeptic neurotransmitter systems. Current symptomatic treatment for AD with acetylcholine esterase inhibitors aims to prevent the breakdown of acetylcholine. Lesions in the cerebral microvessels, e.g., amyloid angiopathy and degeneration of the endothelium, are also found in brains of AD patients. Histopathology is often stated to be the gold standard for a diagnosis of AD. Neuropathological criteria for AD are mainly based on age-dependent limits of the amount of SP in the neocortex, although some criteria are based on the pattern of NFT changes. The typical brain changes seen in AD are also found in high proportions of normal elderly, especially among the very old. Several population-based studies report that only about half of individuals who fulfil neuropathological criteria for AD are demented during life. This would mean that all people with AD in their brains do not develop dementia.

Vascular Dementia

VaD is caused by cerebrovascular disorders. Until the 1960s, old age (senile) dementia was considered a result of chronic ischemia secondary to atherosclerosis of cerebral arteries or hardening of the arteries. In 1974, the term multi-infarct dementia was introduced, emphasizing the importance of multiple small or large infarcts, often related to stroke. Other causes of VaD include subcortical white matter lesions (WMLs) and other cerebrovascular diseases.

In epidemiological studies, where brain imaging (CT or MRI) is most often not performed, the diagnosis of VaD is most frequently on history or symptoms of stroke in connection with dementia onset. Stroke-associated dementia is related to small or large brain infarcts. Most cerebral infarcts are caused by thromboembolism from extracranial arteries and the heart. Although this often gives rise to typical focal symptoms (hemiparesis, aphasia), the infarcts are often too small individually to produce a major clinical incident, which means that the diagnosis cannot be made without brain imaging. Therefore, VaD is often underdiagnosed in traditional epidemiological studies. The typical clinical picture is sudden onset, stepwise deterioration, fluctuating course, history of stroke or transitory ischemic attacks, and focal neurological symptoms and signs. However, VaD may also have a gradual onset with a slowly progressive course and without focal signs or infarcts on brain imaging, which makes it difficult to differentiate from AD. The cognitive impairment may have a large variability depending on the site of the lesions, and memory may be relatively preserved.

The importance of subcortical white-matter lesions (WMLs) as a cause of dementia became clear after the advent of brain imaging (CT and MRI) in the 1980s. The neuropathology includes diffuse ischemic demyelination, moderate loss of axons, and incomplete infarctions in subcortical structures of both hemispheres, as well as hyalinization or fibrosis of the small penetrating arteries and arterioles in the white matter. The main hypothesis regarding its pathogenesis is that longstanding hypertension causes lipohyalinosis and narrowing of the lumen of the small perforating arteries and arterioles that nourish the deep WM. The dementia associated with WMLs is probably caused by subcortical–cortical or corticocortical disconnection. WMLs have been associated with a spectrum of clinical pictures. The dementia is supposed to have an insidious onset and a slowly progressive course, which makes it difficult to distinguish from AD. The typical clinical picture includes mild memory problems, psychomotor retardation, urinary incontinence, gait dysfunction, apathy, loss of drive, and emotional blunting. The main risk factors for WMLs are high age and vascular diseases, especially hypertension. WMLs are also common in normal aging and related to mild cognitive symptoms and gait disturbances in otherwise normal elderly.

The main diagnostic problem in dementia is to distinguish AD from VaD. Depending on the criteria used, the proportion of demented individuals diagnosed as AD or VaD may differ considerably. AD may sometimes have a course suggestive of VaD, and VaD may have a course suggestive of AD. AD may be underdiagnosed in persons with cerebral infarcts as neither clinical nor pathological evidence of cerebrovascular disease means that it caused the dementia. However, AD may also be overdiagnosed as many infarctions are clinically silent and infarcts in cases of typical AD may be dismissed as being irrelevant. The common coincidence of AD and VaD is becoming increasingly recognized and may even be the most common form of dementia. This state is often called mixed dementia, in which neither disease alone may be sufficient to cause dementia, but together they may. It was recently reported that concomitant cerebrovascular diseases increase the possibility that individuals with AD pathology will express a dementia syndrome. Pure forms of VaD are probably rare.

Frequency Of Dementia

The prevalence of dementia increases with age, from approximately 3% at age 70 to 52% at age 95 (Table 1). The figures are uncertain in the very high ages because the number of persons examined in these ages generally has been low. There is an on-going debate whether the prevalence reaches a plateau after the age of 90. Regarding types of dementia, most population studies report that 50–70% of demented individuals have AD and 20–30% VaD, and that the prevalence of AD increases steeply with increasing age, while the prevalence of VaD increases less steeply. One reason may be that silent asymptomatic infarcts become more common with increasing age. In most studies, the prevalence of AD is higher in males than in females among younger old people, and higher among women than among men in the very old. Regarding geographical distribution, the prevalence of dementia is strikingly similar in most parts of the world (although prevalence may be lower in Africa), but there are differences concerning the type of dementia. The prevalence of AD is generally higher in Western European countries and North America, and lower in Asia and Eastern Europe, while the opposite pattern is found for vascular dementia. One explanation for the variation may be that the prevalence and incidence of cerebrovascular disorders differ between countries. More recent prevalence studies from Asia suggest a more similar distribution of AD and VaD to European and North American studies. This may be due to changing diagnostic customs or changes in mortality and morbidity related to cerebrovascular disease.

Also, the incidence of dementia shows an increase with age, although there is a hypothesis that the incidence may decline after the age of 95 years. The relationship between dementia and increasing age has resulted in a debate on whether dementia is an extreme variant of normal aging or different causes of dementia become more common with increasing age.

Risk And Protective Factors

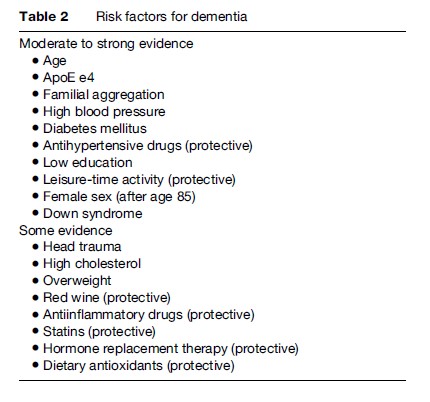

Most studies on risk and protective factors have been published with regard to AD (Table 2). Higher age is the most consistent risk factor. Other factors are family history of dementia, Down syndrome, the apoEe4 allele, head trauma, female sex after the age of 80, and vascular risk factors and disorders. Protective factors include higher educational level, use of moderate amounts of red wine, physical exercise, higher leisure time activity, intellectual activities, and larger brain reserve. In observational studies, the use of antihypertensive drugs, anti-inflammatory drugs, statins, estrogens, and dietary antioxidants are reported to decrease risk of dementia and AD. This has not yet been confirmed in placebo-controlled studies. The risk factors suggested for VaD are similar to those in stroke, including advanced age, male sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and cardiac diseases. VaD is reported to be more common in Finland, the former Soviet Union, and Asian countries than in Western Europe and the United States. Risk factors for dementia in individuals with stroke are similar to those in AD, suggesting that mixed dementia may be common in these cases.

The majority of patients with AD have no obvious family history and are classified as sporadic AD, but there are also rare genetic forms. In these families, the symptoms have an early onset (40–60 years of age). However, sporadic AD is also consistently associated with a family history of dementia. Genetic studies in families with autosomal dominant inheritance for AD, accounting for less than 1% of all AD cases, show that mutations on the genes encoding amyloid precursor protein (APP) on chromosome 21, presenilin-1 on chromosome 14, and presenilin-2 on chromosome 1 segregate with AD. These mutations may elevate the levels of b-amyloid aggregates in the brain. Individuals with Down syndrome (DS) exhibit severe AD neuropathology by age 40. The dominant chromosomal aberration in DS is a trisomy of the long arm of chromosome 21, the site of the APP gene. Alzheimer pathology in DS is probably caused by an overexpression of this gene.

One susceptibility genetic factor, the apolipoprotein E (apoE), has consistently been associated with both familial and sporadic AD. There are three allelic isoforms of the APOE genotype (e4, e3, e2). The e4 is associated with increased risk for AD and the e2 with decreased risk. The association is also confirmed in population-based studies, although it is weaker than in more selected samples and is reduced in the oldest-old. ApoE is a constituent of plasma lipoproteins and is essential in the redistribution of lipids between cells by mediating the uptake of lipoproteins by specific receptors. The apoE e4 acts as an independent and specific susceptibility gene for AD and several hypotheses exist for its pathogenic role. Presence or absence of the apoE e4 has been shown to modify the impact of other risk factors, and is also a risk factor for vascular diseases.

AD has recently been associated with vascular risk factors, such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, and generalized atherosclerosis. Vascular diseases may exacerbate the AD process, or similar mechanisms may be involved in the pathogenesis of both disorders. Those studies reporting an association between hypertension and AD have generally measured blood pressure at least 5–10 years before dementia onset, while studies with shorter follow-ups and cross-sectional studies generally report associations between dementia and low blood pressure. In line with this, it has been reported that blood pressure decreases in the years preceding AD onset and continues to decline during the course of AD. The relationship between declining blood pressure and AD may have several explanations. One possibility is that the declining blood pressure is secondary to the brain lesions seen in AD. Several of the brain regions affected early in AD are regulators of blood pressure. The decline in blood pressure may thus be a very early clinical sign of AD, perhaps even before the cognitive symptoms. Studies showing associations with AD have furthermore generally been based on standardized blood pressure measurements, while studies based on self-report generally do not find associations with AD. One reason for the latter may be that those reporting hypertension may often be on treatment, and a number of epidemiological studies suggest that use of antihypertensive agents decreases the incidence of AD.

Consequences Of Dementia

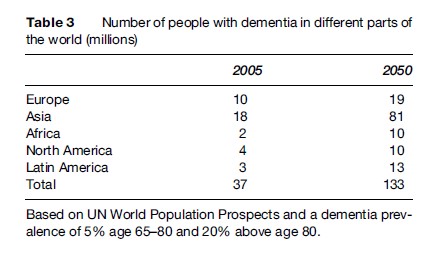

AD is a chronic disorder. During the course of the disease, the patients’ functions in daily living inevitably deteriorate. Dementia is the most important cause of dependency in older adults. The burden of care falls mainly on the family, although AD and dementia are also the most important cause of institutionalization in the elderly. Informal family care is particularly important in those parts of the world where health and welfare services and long-term care are less well developed. The caregiver strain is often immense, and related to an increased risk of depression and other mental disorders. In most countries, both in the developed and in the developing world, specialists are few, and primary health care and other services are ill prepared to meet the needs of families for long-term support and care. In 2003, the cost of dementia worldwide was estimated to be almost US $160 billion based on a worldwide prevalence of almost 30 million demented persons. Ninety-two percent of this cost was found in advanced economies, where only about 40% of the demented were found. Due to changing demographics, with a substantial increase in the number of people aged 80 and above, especially in the developing world, the number of people with dementia will increase substantially, to over 130 million, during the next 40 years. Most of this increase will be in the developing world (Table 3).

Dementia disorders are the most important predictors of mortality in old age. This is true both for AD and VaD, and VaD has a higher mortality rate than AD. Mortality is also associated with severity of dementia and with cognitive function in nondemented elderly. Although the relative risk of death in dementia is reduced in advanced age, the influence of dementia on survival at high ages is substantial because of its high prevalence. At age 85, population-attributable risk (PAR) for death in AD and VaD was 31% in men and 50% in women.

Depression

A depressive syndrome includes symptoms of depressed mood, tearfulness, diminished pleasure or interest, excessive guilt feelings, low self-esteem, and feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, pessimism, emotional flatness, poor appetite and weight loss, low energy, or increased fatigue, sleep problems, poor concentration, difficulty making decisions, intellectual problems, withdrawal, psychomotor retardation, reduced talkativeness or agitation, and suicidal ideations.

Elderly people may be predisposed to depression due to age-related structural and biochemical changes, such as underactivity of serotonergic transmission, hypersecretion of cortisol, and low levels of testosterone. This notion is supported by a worldwide report of high suicide rates in the elderly. Furthermore, several risk factors for depression such as bereavement and other psychological losses, loneliness, loss of earlier status in society, vascular and other somatic diseases, and institutionalization become more common with increasing age. With regard to vascular disease, it has been suggested that cerebrovascular diseases, such as stroke and ischemic WMLs are especially important in the etiology of depression in old age. This has led to the concept of vascular depression. However, depression is also a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke, and related to worse outcome in these disorders. The association between vascular disease and depression is therefore complicated. On the other hand, some age-related factors may decrease the prevalence of depression in old age. Life stressors might be better tolerated in old age because they are expected, and the wisdom seen in elderly people may also be protective. Old age may also have a positive dimension, with freedom of time, less stressors of work, and less competition.

Frequency Of Depression

Most cross-sectional studies report prevalence figures of around 10% for depression, which makes depression an even more common disorder than dementia after age 65. Depression is thus a common cause of disability in the elderly and reduces life satisfaction. Several cross-sectional studies suggest that the prevalence of depressive disorders decreases after age 65. Studies on representative samples that treat the group above age 65 as one entity are, however, heavily weighted towards the age strata 65–75, and the group above age 75 is therefore concealed in these types of studies. Several studies report that depression may have its highest prevalence the 10 years before retirement age (65 years) and its lowest prevalence between age 65 and 75 years, with an increase again after age 75.

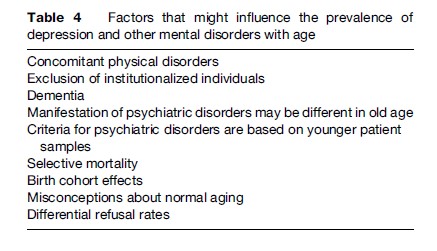

Several methodological and confounding factors may act either to increase or decrease the prevalence of depression with age (Table 4). First, there is an overlap in symptoms of physical disorders and normal aging and depression (e.g., loss of appetite, tiredness, sleep disturbances), which may lead to overdiagnosis of depression. On the other hand, if depressive symptoms are thought to be due to physical disorders or normal aging by the elderly themselves and by their relatives and physicians, the rate of depression may be underestimated. Second, several population studies exclude individuals in institutions, where the prevalence of depressive disorders is high. This has its strongest influence on the prevalence among the oldest old where institutionalization rate is high. Third, most criteria for depression, for example, DSM-IVexcludes organic causes of depression such as dementia. As described above, the prevalence of dementia increases dramatically with age. This means that with increasing age, a large proportion of the total population will be removed from the population at risk for depression, giving lower total prevalence of depression in higher ages. Furthermore, even if the demented are not excluded, persons with dementia may underreport these symptoms due to memory problems. Fourth, depression may have other manifestations in the elderly, i.e., other symptom patterns than those in current criteria. This might underestimate the prevalence of depression in the oldest age groups. Instead, depressive symptoms are reported to be more common than the clinical diagnosis, and, in general, the prevalence of depressive symptoms increases with age. However, the symptoms of depression are most often similar in the old and the young. Fifth, the mortality rate is increased in individuals with depression, also in old age. Thus, even if the risk for depression increases with age, the increased mortality may lead to a decreasing prevalence. Sixth, during the twentieth century, a higher prevalence of depression has been reported in later-born generations. Therefore, even if the prevalence is unaffected by age, the cohort effect may give a lower prevalence in the elderly. Seventh, individuals with depression may be more reluctant to participate in studies. If this differential refusal rate is more accentuated in the elderly, it might lead to a lower prevalence of depression in the elderly.

Risk Factors For Depression

Female sex is the most consistent risk factor for depression. The female preponderance is most accentuated in middle life, and the sex difference is supposed to diminish with increasing age. However, depression is generally reported to be more common in women also among the elderly. There are few studies on other risk factors for depression in old age and most are based on retrospective information from cross-sectional data. It is therefore difficult to differentiate between risk factors and consequences of depression. Declining physical health, institutionalization and several medical drugs have been associated with depression. Several physical disorders are related to depression in the elderly including cardiovascular diseases, hypothyroidism, cancer, vitamin deficiencies, Cushing syndrome, anemia, infections, and lung diseases. Other reported risk factors include previous psychiatric history, family history of depression, bereavement, other life events, personality factors (e.g., locus of control, neuroticism), social factors (social deprivation, loneliness, social support deficits), low education, smoking, and impairments in activities of daily living.

Even if the frequency of depression increases with age, this does not necessarily mean that age as such is a risk factor, as several other proposed risk factors, such as physical disorders, social deprivation, and bereavement, also increase with age. When these other factors are controlled for, age as such may not be an independent risk factor for depression.

Structural brain changes in depression of old age have been reported by several investigators. These changes include ventricular enlargement and changes in the caudate nuclei and the putamen. Ischemic white matter lesions and infarcts have also been associated with depression in the elderly. Most studies are, however, hospital based and may be influenced by selection biases.

Depression And Dementia

High rates of depression have been reported in patients with dementia, with a prevalence of 10–20%. Depressive disorders are generally more common in mild or early dementia. Depression in dementia may be a psychological reaction to the disease, or result from biochemical or structural brain changes. However, a lack of association between dementia and depression has been noted in community studies. Depression may worsen the dementia syndrome and is important to recognize as it is potentially treatable. It has also been suggested that previous depression may be a risk factor for dementia. Furthermore, several studies report that individuals with manifest depression show cognitive decline. This decline is generally of mild degree and not overt dementia.

Consequences Of Depression

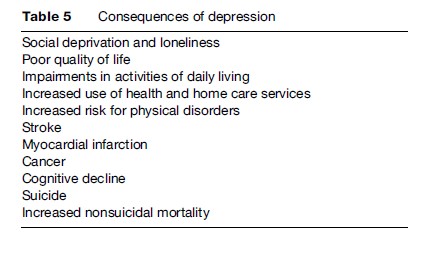

Among the consequences of depression are social deprivation, loneliness, poor quality of life, increased use of health and home-care services, increased risk for physical disorders (e.g., stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer), cognitive decline, impairments in activities of daily living, suicide, and an increased nonsuicidal mortality (Table 5). Studies on attempted and completed suicides in old age have reported a stronger association with depression, with less alcoholism and fewer personality disorders, than in younger age groups. Furthermore, suicidal attempts in the elderly are often characterized by a greater degree of lethal intent. The depressed elderly have a several-fold increased risk of dying. The causal relationship between depression and the increased risk of dying is not clear.

Untreated depression has consistently been reported to have a poor outcome in the elderly, although it is not clear whether the depressed elderly have worse outcome than younger depressives. Several studies have addressed the question of whether it is possible to identify those with a poor outcome. The findings so far are contradictory.

Despite the high prescription of psychotropic drugs in the elderly, only a minority of those with depression receive specific treatment for their disorder. Most epidemiological studies report that only around 15–20% of individuals diagnosed with depression receive antidepressant therapy. Instead, a high prescription of benzodiazepines in depression has been reported by several investigators. Many elderly may use sedatives for sleep disturbances and anxiolytics for the anxiety accompanying depression, where antidepressants should have been the proper therapy. During recent years, new antidepressants, which are better tolerated by the elderly, have been introduced. At the same time, the prescription of antidepressants has increased in the community. It remains to be elucidated whether these changes have led to a higher treatment rate of depression in the elderly.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), agoraphobia, panic anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), social phobias, and simple phobias. Studies concerned especially with the epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the elderly are few. The approximate prevalence figures are for social phobia 1%, simple phobia 4%, OCD 0.1–0.8%, panic disorder 0.1%, and generalized anxiety disorder 4%, while the prevalence of agoraphobia varies widely between studies (1.5–8%). For overall anxiety disorder, figures vary widely depending on criteria used, from 3 to 15%. The prevalence of anxiety disorders is reported to decline with age, also after age 65, with the exception of generalized anxiety disorder, which seem to remain stable with age or even increase (if nonhierarchical diagnoses are made; see below in this section). However, these disorders may occur as primary disorders for the first time in old age. The lower rate of anxiety disorders in the elderly is contradicted by the high consumption of anxiolytic drugs in the elderly. This suggests that anxiety may be an important and underrated problem in this age group. As discussed in relation to depression, the apparent decrease in frequency of anxiety disorders with age may be influenced by birth cohort effects, anxiety-related mortality, cognitive impairment, the exclusion of institutionalized individuals, criteria based on younger and middle-aged persons, anxiety symptoms believed to be caused by physical disorders, and differential refusal to participate in the studies. Another factor may be that the elderly have a different clinical presentation, with less somatic and autonomic symptoms, fewer symptoms, and less avoidance. The requirement that there should be a constriction of normal activities, interference with social or role functioning, and that the individual himself should find the symptoms excessive or unreasonable might also differ by age. Furthermore, anxiety may present differently in the elderly, for example as agitation, irritability, talkativeness, and tension. In most studies, the prevalence of anxiety disorders is higher in women than in men, also among the elderly, but the differences seem to diminish with increasing age.

One important aspect when evaluating frequency of anxiety disorders is whether a hierarchical approach to diagnosis has been made (as in DSM-III and IV and ICD-10 criteria). In such a hierarchy, most anxiety disorders cannot be diagnosed in the presence of concurrent depressive illness. However, anxiety disorders and depression often occur together, also among the elderly, with a reported comorbidity of 75–90%. This has an immense influence on the frequency of anxiety disorders in the population. If comorbidity between depression and anxiety is higher in the elderly, this might explain some of the decrease in frequency of anxiety disorders with age. In fact, the frequency of GAD decreases with age when hierarchical diagnosis is made and increases without a hierarchical system. Another possibility is that individuals with anxiety disorders have an increased risk to develop a depressive disorder, thus shifting their diagnosis from anxiety to depression with increasing age. However, there also seems to be a shift in the opposite direction with increasing age. In the discussion about new criteria, it has been suggested that depression and generalized anxiety should be lumped together as one category. Finally, thresholds for making diagnostic cases seem to be especially important in relation to frequency of anxiety disorders.

Among the consequences of anxiety disorders are an increased mortality rate, increased risk for ischemic heart disease and stroke, and an increased suicide risk. Anxiety disorders seem to be especially common in mild dementia.

Psychosis

The term paraphrenia was previously used to describe psychotic syndromes in the elderly, Currently used terms are late-onset schizophrenia or late-life psychosis, encompassing delusions and visual and auditory hallucinations arising in late life. Compared to early-onset psychosis, late onset cases have better preserved personality, less affective blunting, less formal thought disorder, more insight and less excess of focal structural brain abnormalities and cognitive dysfunction compared to age-matched controls. The prevalence of psychotic symptoms is high among the demented elderly, ranging from 45 to 50%, while psychotic symptoms and disorders such as schizophrenia are supposed to be rare in the nondemented elderly. Population studies in nondemented elderly are generally based only on self-report and give prevalence figures for psychotic symptoms from 2 to 3% in populations above the age of 65 years. According to currently used criteria, psychotic disorders are even less common, with reported prevalence ranging from 0 to 5%. There are several methodological factors that might explain the low prevalence of psychotic symptoms and syndromes in elderly populations. First, there might be underreporting because the elderly are reluctant to report psychotic symptoms. Recent studies have reported that up to 10% of nondemented elderly above age 85 have psychotic symptoms if information from other sources than self-report (especially close informants) is used in the assessments. Second, individuals with psychotic symptoms are likely to refuse participation in population studies more often than other elderly. Thirdly, as for other psychiatric disorders, diagnostic criteria are developed in young or middle-aged patient samples.

Factors related to late-life psychosis include female sex, previous schizoid and paranoid personality traits, being divorced, living alone, lower education, poor social network and isolation, low social functioning, sensory impairments, especially deafness, and more dependence on community care. Psychosis and psychotic symptoms in elderly populations have been associated with a variety of psychiatric and somatic disorders, such as depression, hypothyroidism, cancer, cerebral tumors, epilepsy, and cerebrovascular disease. Furthermore, many drugs, such as anticholinergics, antiparkinsons, psychostimulants, steroids, and beta-blockers can produce psychotic symptoms in the elderly. Other causes are alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal. Studies on the relationship between psychotic symptoms and structural brain changes in the elderly report disparate results. Some studies report a higher ventricle-to-brain ratio, larger third ventricle volume, and volume reductions of the left temporal lobe or superior temporal gyrus. Also, ischemic white matter lesions have been reported in late-onset schizophrenia. Basal ganglia calcifications have also been reported in elderly individuals with psychotic symptoms.

Among the consequences of psychotic symptoms are impairment and disability in daily life, dependence on community care, and cognitive dysfunction. Individuals with late-onset schizophrenia perform significantly worse than age-matched controls on a variety of cognitive tests, although the difference is not as accentuated as for younger age groups. Psychotic symptoms, like most other psychiatric conditions in the elderly, are related to an increased mortality independent of physical disorders. Psychotic symptoms may also be a prodrome of dementia. In Lewy body dementia, early visual hallucinations are even part of the criteria. However, psychotic symptoms frequently accompany dementia disorders and are regarded to be more common late in the course of the disease. The cumulative incidence of hallucinations and delusions for patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease is reported to be more than 50% at 4 years.

Alcohol And Drug Abuse

Few epidemiological studies have examined frequency and risk factors for alcohol problems in old age. There is a general decline in alcohol consumption with increasing age, and alcohol problems or abuse are generally believed to be less common among the elderly than in younger populations. One reason may be that alcohol abuse is related to premature mortality. Another reason may be that instruments and diagnostic criteria are developed from younger age groups, and may not be valid at older ages. Birth cohort effects may also influence the results. In epidemiological studies, self-report probably underestimates alcohol problems, due to neglect or early memory problems.

The prevalence of alcohol problems is generally higher in men than in women. Physical and psychiatric disorders, especially dementia and depression, are more common among elderly alcoholics than among other elderly. Increasing age also makes individuals more sensitive to the effect of alcohol to the body. It has been discussed whether late-life alcohol abuse presents differently than alcohol abuse in younger ages, for example, by cognitive dysfunction, falls, self-neglect, incontinence, and malnutrition. Late-onset alcohol abuse may start in connection with bereavement, but may also be an early manifestation of a dementia disorder. Elderly early-onset alcohol abusers are a group who survived into old age, despite the increased mortality in alcohol abusers. Alcohol abuse in the elderly often co-exists with abuse of psychotropic drugs, leading to interactions. There are indications that elderly alcohol abusers who abstain from alcohol may improve in activities of daily living, suggesting a benefit of abstinence.

Multiple medications, drug interactions, and age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes in the elderly affect drug response and increase the risk for adverse effects, such as delirium and falls. The elderly have a high rate of psychotropic drug use, with figures ranging from 45 to 50% among octogenarians, with lower figures among younger elderly. The highest rates apply to anxiolytic sedatives, mainly benzodiazepines. Women generally have higher rates than men. The extent to which the high use of benzodiazepines reflects drug abuse needs to be elucidated.

Bibliography:

- American Psychiatric Association (1987) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Third Edition Revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- World Health Organization (1992) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Blazer DG and Hybels CF (2005) Origins of depression in later life. Psychological Medicine 35: 1–12.

- Blennow K, de Leon MJ, and Zetterberg H (2006) Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 368: 387–403.

- Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, et al. (1997) Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta-Analysis Consortium. Journal of the American Medical Association 278: 1349–1356.

- Johnson I (2000) Alcohol problems in old age: A review of recent epidemiological research. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 15: 575–581.

- Jorm AF (2000) Does old age reduce the risk of anxiety and depression? A review of epidemiological studies across the adult life span. Psychological Medicine 30: 11–22.

- Krasucki C, Howard R, and Mann A (1989) The relationship between anxiety disorders and age. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13: 79–99.

- Ostling S (2005) Psychotic symptoms in the elderly. Current Psychosis and Therapeutics Reports 3: 9–14.

- Palsson S and Skoog I (1997) The epidemiology of affective disorders in the elderly: A review. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 12 (supplement 2): S3–S13.

- Riedel-Heller SG, Busse A, and Angermeyer MC (2006) The state of mental health in old-age across the ‘old’ European Union – A systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 113: 388–401.

- Skoog I (2006) Vascular Dementia. In: Pathy MSJ, Sinclair AJ and Morley JE (eds.) Principles and Practice of Geriatric Medicine, 4th edn., pp. 1103–1110Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

- Skoog I and Blennow K (2001) Alzheimer’s disease. In: Hofman A and Mayeux R (eds.) Investigating Neurological Disease. Epidemiology for Clinical Neurology, pp. 154–173. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

- Skoog I and Gustafson D (2003) Vascular disorders and Alzheimer’s disease. In: Bowler JV and Hachinski V (eds.) Vascular Cognitive Impairment. Preventable Dementia, pp. 260–271. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

- Wimo A, Jonsson L, and Winblad B (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and direct costs of dementia in 2003. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 21: 175–181.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.