This sample Business Disorganization Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

The idea that artists’ work can usefully inform business practice has gained support in recent years. Managers have long described some business activities as “more art than science.” By this, however, they have usually meant that they do not understand the activity and cannot do it reliably themselves. In this view, artistic methods and art-like activities are personal and intuitive—even magical—not yet sufficiently analyzed, routinized, or rationalized to be trustworthy. Authors such as Adler (2006), however, note that an increasing number of companies are abandoning the notion that art practice within business signifies a problem; they have embraced artistic processes in approaches to strategic and day-today management, leadership, and teamwork. Management researchers, too, have drawn practical lessons from artistic methods in design (Bolland & Collopy, 2004), music (Hackman, 2002; R. Zander & B. Zander, 1998), theatre (Austin & Devin, 2003), and other areas. Scholars have also proposed art principles and art-based philosophies as organizing bases for business firms (Guillet de Monthoux, 2004) and as conceptual lenses through which we can more completely understand organizations (Strati, 1999).

One possible reason for the emergence of art practice as a candidate model for business practice is the growing economic importance of “knowledge work” in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. We used to think in units of “horse power.” A horse leaning into its collar, tugging a weight, is an excellent metaphor for our traditional idea of work: force exercised upon solid objects. In knowledge work, however, we do not move weight. We collect information, organize data into knowledge, and make value-creating transformations that occur in the realm of ideas; according to Drucker (1959), knowledge work is “based on the mind rather than on the hand” (p. 120). A lot of this mind work is now done on computers and involves changes of electronic state rather than of physical position, size, or shape. Rapid growth has underscored the economic importance of entirely new knowledge work job categories such as digital effects artist, drug researcher, graphic designer, software engineer, or product stylist. Such work often involves innovation, an effort to generate outcomes that are valuable because of their novelty. Although artists may employ different (not “business-like”) criteria to decide what constitutes a valuable outcome, most are, in one way or another, striving for outcome novelty (“originality”) that they and others consider valuable. The ways they create these valuable novelties may, we now understand, suggest ways to improve business practice.

The men and women who do innovative work differ in important ways from those who do routine industrial work. Often they are highly skilled individualists, people who act more like artists than like assembly-line workers.

Most value work for its own sake, not just for the wages. These distinctions have far-reaching consequences for the men and women who lead and manage this kind of work. Many of these consequences issue from the fact that these workers usually know more about what they are doing than their managers can. Even more difficult, when artistlike knowledge workers get together in teams, the novelty they produce tends to proliferate exponentially; they dash into unpredictable areas. The synergy of their combination can thrust managers into a state of watchful—even fearful—anxiety.

An impediment to artful collaboration, more potent than a fear of ambiguity and uncertainty, is this: How do you assign individual credit and blame to the work of a group? We take our usual metaphor, our category for thinking about working together, from athletics. We designate teams. Teams, however, can be a poor metaphor for collaborative work. Teams work together, but they do not collaborate in the way that artists do. A team often has clearly marked tasks, roles, and areas of expertise. Athletic teams think of winning or losing. Business teams tend that way, too. An artful work group, in contrast, relies on interdependency among the members and honors the unique contribution of each as essential material for the group’s final outcome. We do not have a business term for this kind of work group. In music and theatre, it is called an ensemble. When an ensemble replaces one member, the entire ensemble becomes a new group, and everyone must reconceive the way they work with each other.

The strategic importance of innovative work increases daily, especially for firms in developed economies, as noninnovative, routine work moves to places where it can be done at lowest cost. Countries such as China and India, with nearly infinite supplies of cheap labor, can create industrial companies and brands that will be difficult for Western firms to outcompete on cost. A company in Australia, Europe, Japan, or the United States that says to its customers, “Buy my product/service; it’s just as good as theirs, but it’s cheaper,” may already be seriously threatened. Strategy experts (e.g., Porter, 1980) tell us that the viable alternate strategy urges customers, “Buy my product/service; it costs more than theirs, but it’s better.” To convince customers to pay a higher price, however, products and services must have aesthetic appeal as well as equal or superior functionality. In fact, because aesthetic appeal is more difficult to comprehend and replicate than functionality, an art-based strategy might be the most effective one a firm could adopt to compete with products and services from “offshore.”

This shift in the nature of work and business value creation has created needs we did not have back in the day when art and industry were safely separate. We need new categories for thinking about work and its outcomes. The ones we are likely to have, drawn from experience of manufacturing as the model for making physical things, do not help us think clearly about making digital things, idea things, and services. We need also to know more about the nature of value creation when it arises not from processes that become ever more efficient in producing consistent outcomes, but from processes that consistently produce valuable inconsistency, or valuable novelty. This kind of value creation rubs us the wrong way if we acquired our business reflexes through industrial experience (and business schools), but for artists it is second nature.

Before we describe the principles, processes, and practices that art suggests for business, we must first take up a basic misconception about how artists do their work. The phrase disorganization in the title of this research-paper suggests this misconception. Although the idea has no published defenders that we know of, many (perhaps most) business people often seem to believe that making art and making business value have nothing in common—that business requires qualities of order, constraint, discipline, and rigor that artists know nothing about. This could not be further from the truth. Art, indeed creativity of all kinds, means making new things, but that emphatically does not mean that artists can do whatever they want to. Many accept deadlines as unforgiving as any in business (e.g., a theatre’s opening night: the tickets are sold, and the curtain will go up on the appointed evening at the appointed hour). Our research (Austin & Devin, 2003) suggests that art making involves processes as rigorous as any in business.

Randomness, Disorder, And Chaos In Artful Process

Donald Campbell (1960) proposed an influential model of creative process based on Darwinian evolution. It can help us understand why artful process often seems disorderly—even chaotic—when viewed by people not trained or experienced in art. Figure 48.1 illustrates his simple, two-stage model. In the first stage, a maker (individual, group, or organization) creates novelty by generating variation. The Campbell model specifies a particular form of variation, “blind” or random variation; as we shall see, it will be useful to relax the assumption of randomness to consider other kinds of variation. In the second stage, the maker “selectively retains” some of the varied outcomes and discards the rest. To make value judgments, the maker uses criteria that he or she may never explicitly define. Makers may use better or worse criteria, or have different levels of ability to see value in the various outcomes. Although the Campbell model does not specify a third phase, different makers might also be differently skilled in exploiting the outcomes they retain.

Figure 48.1 The Campbell Model of Creative Process

Figure 48.1 The Campbell Model of Creative Process

If we take seriously Campbell’s model of creativity, we must assume some degree of disorder at the beginning of an innovation process. Such randomness could be inside the mental processes of a creative individual, as some have proposed (e.g., Simonton, 1999). Group processes, however, often explicitly depend on disorderly accident. The history of great inventions and discoveries abounds with examples of accidents that an inventor or discoverer recognized as a vital piece of some creative puzzle. (See Gratzer, 2002 for many examples.) In our own research, we have found examples of artists who intentionally cause “accidental” outcomes. One renowned potter, for example, made a habit of hitting his beautifully formed urns with a stick as they dried to achieve shapes that he could not plan or predict.

Variation generated by human agents, however, is not usually purely random. People are not effective randomization devices. If we consider nonrandom variation, we can imagine people having different tendencies toward varied outcomes and different abilities to produce outcomes that are, somehow, interesting. As long ago as 1950, Guilford observed that some people tend toward divergent mental “production” (they imagine many possible solutions to a problem), while others tend toward convergent production (they focus on deducing a single solution). Artists, by training and practice, tend toward divergent thinking. They see imagination as a tool, not a distraction.

Selective retention involves convergent thinking, of course, at which artists may also be particularly practiced and skilled. Louis Pasteur (1854/1954) famously referred to the “prepared mind” as a capacity to recognize value that no one else can see in chance outcomes, Cohen and Levinthal (1990) expanded this notion and applied it to groups and organization, using the expression absorptive capacity to label skill in recognizing value. They identified the primary kind of preparation for this capacity: the amount of knowledge that people within a firm have accumulated about knowledge of the area of innovation that is available outside the firm. As we shall see, artists have something further to teach business managers and scholars about the kinds of preparation that enhance the capacity to recognize value.

The possible presence of randomness within a creative process does not mean that the process is disorderly or chaotic. Artists often work by a rigorous process of creating variations and then deciding what to discard and what to keep. In some art forms, this is called “rehearsal.” In others, it may be some form of practicing, sketching, or collecting of ideas that either directly applies directly to the current project or “might come in handy” some day. Such preparation requires a high order of discipline and skill.

Any particular business, however, may suffer disorganization. Chaos may take over a process for any number of reasons. Here, too, the artful mind has an advantage: accustomed to creating form, to seeing form develop and emerge as a normal part of the making process, an artful observer is not uncomfortable in the presence of ambiguity or even chaos. Chaos looks like potentially interesting variation. Ambiguity looks like a desirable license to make choices about what to select. Tasked with understanding and reconceiving a disorganized process or organization, the artful maker can begin at the true beginning, unhampered by the baggage of preconceptions brought along with industrial categories.

Artistic Methods As Models For Business Practice

Artistic methods offer surprisingly productive ways to think about business organization. At first, of course, like anything new, artful organization appears formless and, perhaps, even threatening or dangerous. When audiences first heard Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, they did not know what to make of its startling originality, its break from the past.

At first critical response was guarded. On February 13, 1805, readers of Leipzig’s Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung read this report: “The reviewer belongs to Herr van Beethoven’s sincerest admirers, but in this composition he must confess that he finds too much that is glaring and bizarre, which hinders greatly one’s grasp of the whole, and a sense of unity is almost completely lost.” Opinion about the Third Symphony shifted rapidly. By 1807 nearly all reactions to the piece were favorable, or at least respectful, and critics were starting to make sense of its more radical elements and accepting it as one of the summit achievements in all of music. (Philharmonic Society of Orange County, 2007)

When Pierre Monteux conducted the world premier of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, the Paris audience erupted in outrage and threw vegetables at him and the orchestra. The piece is now a standard of the orchestral classical repertoire and does not sound revolutionary to our ears. We have already absorbed enough of the world of Stravinsky to turn what was ugly to sophisticated ears in 1913 into something that seems normal (though certainly not ordinary!) to the most innocent ears today. Some ways of organizing work along artistic rather than industrial lines will have a similar effect on workers and managers alike. Those committed to the way “we’ve always done it” may panic; those with new categories for how to work will start hearing the tune.

Categories derived from artful organization, from an artful frame of mind, are good for looking at (and seeing) new forms. The artful mind seeks form in the organization of internal principles that derive from the current moment or task, not in externally derived, preplanned, or mechanically applied instructions or specifications. This artful skill of seeing patterns form is very like long experience in other realms. For example, the experienced fisherman looks at the dawn sky, smells the air, feels a breeze from the South, and knows he had better be back in port by noon. Sure enough, by noon the wind has backed into the North and has whipped the bay to a lathery froth. How did he know? Because he has seen many early mornings on his bay. Features of the water, air, and sky that have no meaning to the less experienced speak volumes to him. An artist sees a new form in a similar way and understands things that do not show up on an apparently calm surface.

New forms are notoriously hard to recognize, even when they are right in front of us. When we add to that fact our natural distrust, even fear, of innovation, it is clear that change, even necessary progress, can be hard to accomplish. The familiar has at least the virtue of familiarity. We know where we stand. Who knows what might happen if we do something different?

A composer friend told us a story about his first composition class at the Eastman School of Music. Without saying anything, the instructor put on a record, and just played the piece. To the class, it sounded like white noise. It lasted maybe three minutes. The instructor stopped the record player and began the class. The next day, the instructor did the same thing: the class began with three minutes of white noise. By the third repetition, the guy who turned out to be the class genius started tapping his pencil to the “noise.” By end of the next iteration, most of the class pencils were tapping to a piece for pianos and percussion by Bela Bartok. These young composers learned to look past the new sounds and perceive the new form. Needless to say, this is a very nuanced example of the idea of a prepared mind.

The Artistic Sensibility: Principles, Process, And Practice

Research in this area allows us to point out some specific artful principles, process characteristics, and practices that offer potential benefits to business firms.

Artists as Makers

Artists make stuff. They all have that in common. Painters, poets, sculptors, and composers all will sooner or later tell you, “I like to make things.” Therefore, if we want to look at business processes with an artful sensibility, it is helpful to conceive of business as a kind of making. Confronting an example of apparent disorganization, then, the artful manager might ask, “What is being made here? What is it made of? Who is doing the making?”

Seeking answers to these questions (instead of, “What is the problem to solve here?”) will lead to an examination of relationships among the different parts of the thing being made. “What are the parts to this thing? How do they fit together?” If these relationships feature interdependence, this situation could appear disorganized when approached with an industrial sensibility but could present differently and coherently to an artful sensibility.

Business As Making

It is hard to know what we see when we look at a complicated system because it will not hold still for analysis. We need a way to stop events in imagination, a calculus. One such calculus, useful when we conceive any process as making, distinguishes it into four principle elements:

A MAKER, who performs operations on

MATERIALS, changing them toward an emerging

FORM that they would not naturally achieve for a

PURPOSE that also emerges from the process and differs according to your point of view.

Let us look at a brief description of each of these.

Maker

A business system or a team project has many makers. First maker is the individual—you, for example. If you think of yourself as making an idea to bring to the meeting, you can consider the materials you use to do that. This will put you in position to make trackable changes in your thinking.

Second maker is each of the other team members, considered individually. Each functions as you do, making ideas from his or her own materials, offering those ideas as material for the third maker, and using others’ ideas as material for the next idea.

Third maker is the group (team, ensemble, system) itself, conceived as a whole greater than the sum of its parts. To achieve maximum flexibility, a group may take time during its process to remark on, or be aware of, its ways of working. This ensures that the group can make deliberate changes in method, in materials, or in the potential of an emerging form.

Materials

What “stuff” gets changed on its way to a form? If you are a sculptor, it might be stone. If you are a financial officer, it might be facts, figures, and your thoughts about them. These materials might be data from the past, projections for the future, instructions for intermediate processes, or even the dream you had. Anything is good material, as long as a maker takes the trouble to know what it is and what he or she can do with it.

Form

People often use this word to refer to a thing’s visual appearance. That is not enough. Form, in this conception, is the organizational principle of the made thing, its internal coherence as well as its appearance and functionality. This kind of making process begins in imagination with an idea for a form (either a thing or a function), and then the actual thing (product, service, idea) emerges from the actions of producing it. In many cases, the work of making and the form that it makes are the same. A service, for instance, exists only as it is actually being made. In that case, the process of making is the thing made.

Theatre art is a good example here. A play (not a script) exists as you watch and listen; when it is over, there is no play left, except in your memory. This convergence of process and product is less obvious in business situations except when team members treat work as worth doing for its own sake. Then the dominant form, the thing made, becomes the event of making it; the residue left by this process may be a saleable product. That is, the team approaches the condition of an artist, working for the sake of the work and trusting that impeccable methods will yield valuable outcomes. One artist, who the Artful Making research team interviewed, told us that he left scratches and imperfections on his engraved plate; they were part of “the history of the event.” We saw the object as a static print on paper; he had a more interesting view. When he told us about it, we could take the more interesting view and our pleasure in the print (its value for us) increased accordingly.

In a productive collaboration, unpredictable form emerges from the work. More often than not, however, a person looking back at the making process will see that what emerged was inevitable.

Purpose

Why make this thing? Any object or service provides various answers to that question. In art, the thing itself, the emerging form, has the purpose of being beautiful, the best of its kind that it can be. Even the most austere artist, however, will have getting up the rent in the back of his or her mind: Can I sell this thing? Experience tells us that for most art, no one can predict the market; art-like business products and services such as movies and video games have this same characteristic (in technical terms, the returns across outcomes have a Pareto distribution with infinite variance, so point estimates—such as averages in forecasts—are of little use). Then, to add complexity, each person in a collaboration will have individual purposes that the process can accomplish. Because all the team members contribute to the final product, it may be difficult to assign a single purpose.

In most business situations, however, the overarching purpose to create value for customers, the firm, the stakeholders, and the general advantage exists. The four-pronged way of looking at making can help you avoid losing your way and prevent you from aiming at some predictably mediocre product rather than an innovation that can move you and the firm ahead.

Interdependent

To conceive a relationship of interdependency among all the elements of a process and its product marks the shift from industrial to artful methods and thinking. Industrial work requires modularity, isolation of each part from every other, to avoid confusion and quality problems. An industrial sensibility sees interdependency as hopeless confusion and disorganization to be avoided at all costs. An artistic sensibility sees interdependency as the heart of any interesting process, as the source of potential novelty and value. We can look at it as two kinds of collaboration. First is the collaboration among the work team members. Each uses the work of the others as material: you bring an idea to the table, and instead of rejecting it or compromising with it, I use it in combination with my ideas to make the next idea. This continues back and forth. Second, as noted earlier, is the collaboration among the materials and functions themselves: if you change one, you change them all.

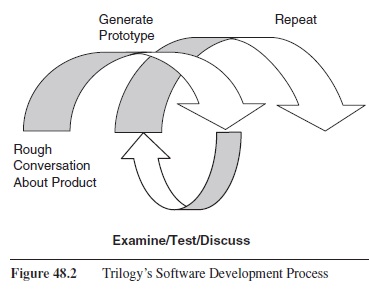

Iterative Process, Emergent Form

If maker and materials depend on one another, the outcome will, in turn, depend on their combination. In other words, the interaction among them will produce changes in the possible outcomes (form and purpose) of the making process. Artful organization directs iterative work toward a product organized by internal principles that emerge from the making process itself. This contrasts with the sequences of industrial systems that begin at carefully planned step one and move through carefully planned step n. Iterative work replaces planning with cheap and rapid prototyping. Each iteration forms a part of every one that follows and moves toward an emergent and often unpredictable outcome. Trilogy, an Austin, Texas, software firm, for instance, uses an iterative, prototyping-intensive process like the one depicted in Figure 48.2, to converge, over time, toward the moving target of what its customers really need (Austin & Devin, 2003).

Figure 48.2 Trilogy’s Software Development Process

Figure 48.2 Trilogy’s Software Development Process

Emergence derives from the interdependence among the parts of making, and the artful frame of mind sees this as evidence of collaboration. The parts of making can be conceived as collaborating with each other; this makes it sensible to propose collaboration as a complementary method of relationship among the different members of a making group. Collaboration, the way artists mean it, naturally results in innovation. A collaborative process cannot achieve a preplanned goal because there is no telling what will emerge when the elements of the process and the members of the project interact.

In their making, artists prize evolutionary change; an original, unpredicted outcome emerges in a fairly orderly, step-by-step way. Scarily, but often more desirably, a process may include a quantum leap, a sudden innovation that is unpredictable but that, in hindsight, seems inevitable. Highly prized, but rare, some innovations and insights come along out of the blue, sometimes by sheer accident. Again, such work appears disorderly and retrograde to an industrial sensibility.

A collaborative work process can achieve general goals, such as making a new product or play, but not specific goals, because there is no telling what will happen when the elements of the process and the members of the project interact collaboratively. The artful sensibility reconceives goals into results—what happens as a result of the process. The art of play making provides a good example. The cast and director begin their work with a general notion of what their play is going to be when they get it made. They know, for instance, the words that characters will use, but the music of their saying will emerge in rehearsal. Their daily work refines and develops that general notion, often changing it beyond casual recognition. Rehearsal ends on a certain date. Because a play must be made anew for each performance, however, the work never ends until the run is over. In play making or product development, seeking a goal that is too specific is often a mistake because it prevents valuable results.

This feature of theatre art has its place in business—an increasingly important place as the world moves from a product economy to a service economy—for a service is like a play: It exists only while it is being made. The salesman cannot just punch a button and sell a car. He must consider all four aspects of his making and adjust each to the ever-changing situation that is his interaction with the customer. Each individual play or sale achieves closure, but the work of making plays and sales does not.

Some Implications Of Artistic Sensibility And Methods

Approaching business in an artful frame of mind will give rise to considerations that might not apply to an industrial approach. Here are some of the ideas that emerge from the research in this area.

Failure

Emergent process has the interesting and useful result of forcing a reconceiving of the concept of failure. Failure, like innovation, has received renewed attention in business magazines. “Fail often to succeed sooner,” a variously attributed maxim, captures well this new emphasis on failure as a means to valuable ends. In its very nature, an iterative process will include ideas and actions that do not, in themselves, constitute the final answer. Yet, each iteration in a process might be a necessary step on the way to closure. In climbing the stairs to the second floor, you would not regard step one as a failure because it did not get you to the top. Step one does not get you all the way there, but you will not get there without it. In this view, when we call a necessary step in a process a “failure,” we are torturing language, naming two contrasting things (a setback and a step forward) with the same word. Moreover, and perhaps even more important, each iteration, as material for the next, remains in the final product. It may not be visible, but it is there. That first step is an integral part of the last one, and the last one, in a collaboration, may well be wondrous.

External Variation, Accident

Much of our business training considers the ambiguity and uncertainty of emergent processes as unacceptable. How can we get anywhere if we do not know where we are going? The artful frame of mind requires a change in this way of thinking—a shift in your creative attention from making a perfect product to making an impeccable process. As soon as you agree to collaborate, to admit the interdependence of the elements of making or the ideas and efforts of the group members, you have said good-bye to any comfortable, plodding path of well-worn steps toward a foreseeable outcome.

In the 1830s, Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre was at work on what would become known as “photography.” One day he put a plate bearing a faint image into a cabinet, intending to clean and reuse it. When he fetched it several days later, he found the image greatly improved. He hypothesized that one or more vaporous chemicals stored in the cabinet had intensified the image.

He put new plates in the cabinet and removed the chemicals one by one. When all the chemicals had been removed, the images still intensified. He examined the cabinet and finally found a few drops of mercury spilled from a broken thermometer. He correctly concluded that mercury vapors caused the images to improve (Roberts, 1989) We see in this example interplay of intention and accident—iteration that includes both the intended and the unexpected—which becomes material capable of making value.

Any book on the history of discovery in science will include dozens of similar examples; any understanding of modern business practice will include an appreciation of accident and a high tolerance for the ambiguity of creative progress.

Control Through Release

Creative progress and interdependent work methods, and knowledge and service work in general, require management techniques quite different from those developed to optimize industrial work. We have noted that the people who do knowledge work tend to be individualistic and self-motivated. It may be even more important that knowledge work managers often suffer a serious difficulty: The people they manage nearly always do things that the managers themselves cannot do.

This situation requires that managers create a confidence in their process and the capabilities of their work team members that may be difficult to sustain. The knowledge work under their supervision may appear to them formless and strange, disorganized, and even chaotic. They must learn to guide the teamwork not by restraint and rules, but by release and freedom from expectations. Control by release means aiming rather than restricting and encouraging rather than thwarting. Most of all, it means a willingness and skill to adapt an emergent novelty to the demands of the business situation. The creativity of managers escapes notice when they are bound by expectations and goals—when they drive their teams to preconceived outcomes and externally determined quotas. That creativity becomes essential when interdependence and collaboration throw preconceptions out the window and present something brand new.

Ambiguity

Much of business training considers this kind of ambiguity and uncertainty unacceptable. An artful sensibility, however, welcomes the creative opportunity of an open-ended project. Creative managers and knowledge workers shift their attention from making a perfect product to making an impeccable process. It is an article of faith that a good product will emerge from a good process. That faith requires an embrace of the inevitable ambiguity of creative process.

Some Useful Features Of Artistic Method

The following are some brief descriptions of things to look for in an organization or process that appears disorganized, but that may instead be artfully managed.

An Emphasis on Preparation Over Planning

Artists can be preparation fanatics. Paul Robertson, leader of a world famous string quartet, told us,

A Beethoven quartet, for example, took 300 hours of ensemble rehearsal (not counting individual practice hours) from the moment they decided to start learning it to the first public performance. . . . For any really significant repertoire, I would expect a piece to take five to ten years before it really became something . . . I think of our concerts as rehearsals . . . opportunity to make a revision of opinion, because this performance is a preparation for the next one. (Austin & O’Donnell, 2007)

Plan so that you can do what you know you want to do. Avoid surprises. There is a need for planning in any work system. The trick is to know the place of that need and relegate planning to that place. The quartet’s performances, for instance, took planning. Audience, running crew, and musicians showed up at the right place and time.

Prepare so that you can do whatever becomes necessary, such as responding productively to unpredicted inputs, surprising results, and new developments. Since each audience affects the performance differently, the quartet must be ready for anything. No two performances are alike for them.

Planners create conditions for others to work in. An artful manager plans the operation, makes a space for the work, staffs the project, and prepares to respond to what happens when the group sets to work. In some cases, the object is preconceived, a goal that must be met. In such a case, the manager keeps the group on task and avoids diversion of resources from the target. Some cases, however, require an innovation, something new under the sun. Then the manager releases the team to work toward outcomes no one has yet imagined.

Meanwhile, the project team prepares, individually and as a group, for the unpredictable process of collaborative iteration. This, to the industrial eye, will appear chaotic and counterproductive. An artful eye will pounce on unforeseen outcomes and put them to work in unpredictable ways.

A Distinction Between Problems and Difficulties

Knowledge work managers often realize that they need to rethink what they know about kinks in the system. Problems require a solution that makes them go away. Seeing problems traps managers and workers in a simplistic view of work and work processes. A complex system offers few solvable problems, errors, or glitches that will go away at the touch of a consultant’s wand. Instead, a system routinely presents open-ended difficulties that will require constant and adaptive address for as long as the system operates and that, artfully viewed, can usually be reconceived as opportunities. The artful sensibility will be comfortable in this kind of ambiguity and will prepare itself to cope with whatever happens rather than get stuck with answers to questions no one is asking.

A Welcome for Serendipity and Accident

If you can plan it, how new can it be? The best source of new answers, of innovation generally, is collaboration. When people collaborate, work together, and use each others’ ideas as material to develop their own, new things happen, no matter what. This can be troubling to the business side of a business: Innovation cannot be planned for or predicted. How do you make a budget for something you cannot predict? Almost no one likes this kind of ambiguity at first.

Think back to the story of Daguerre and his accidental discovery of mercury as an intensifier of images. In science, it has long been understood that many (some have said most) important advances are the result of accident. They come at us from left field, unannounced. The great scientists recognize them; ordinary ones do not. No one has any idea how many cultures of penicillin Arthur Fleming colonized before he noticed something weird and investigated to find something wonderful. Consider this story, told by August Kekule von Stradonitz, one of the founders of organic chemistry. He “discovered” the shape of the benzene molecule (a ring) in a troubled dream.

I turned my chair to the fire and dozed . . . the atoms were gamboling before my eyes . . . My mental eye, rendered more acute by repeated visions of the kind, could now distinguish larger structures of manifold conformation: long rows sometimes more closely fitted together all twining and twisting in snake-like motion. But look! What was that? One of the snakes had seized hold of its own tail, and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes. As if by a flash of lightning I awoke . . . and spent the rest of the night working out the consequences of the hypothesis. (Gratzer, 2002, pp. 10-11)

A shift from industrial to artful thinking welcomes serendipity and accident. Some artists arrange accidents to introduce variation and unpredictability. In theatre rehearsal, it is common practice for a director to arrange surprises for the actors, new conditions that will upset their preconceptions, result in new ideas, and lead toward more complex and interesting outcomes. Real collaboration, of any kind, always produces surprises.

Form Over Content, Process Over Outcomes

Instead of asking, “What is going on here?” the artful sensibility asks, “What are the parts to this thing? How do they fit together?” The artful person notes the parts, with special attention to their arrangement, to the various ways they repeat as the process moves in time, and to the interdependent relationships among the different parts. Confronting a disorganized business process, an artful sensibility focuses not on the flawed product or the dysfunctional arrangements, but on the form—the relationships among elements of the process.

Increasingly, as knowledge work and a service economy become the business norm, process and product merge. For a service, obviously the two are the same: Making the service provides the service because providing the service requires making it each time. Indeed, the service does not exist except while you are making it.

In an artful, iterative process, the product emerges from the process, as does the process itself. We have seen emergence as a function of the interdependence among all the parts of making. Artful flexibility accepts and uses outcomes no matter how surprising.

Managing to Closure

In an iterative process, deciding on closure is nonobvious and often requires sophisticated judgment. A painter once told us, “I know the painting’s done when I have to think about the next brush stroke”; the simplicity of this statement conceals an underlying criterion for closure, the result of hard earned learning about how to avoid overworking a painting. This painter, we might also note, seems to have had no deadline or schedule. Such license rarely obtains in business. When there is a deadline, when the product must be ready by a certain date, a manager must carefully modulate the rate of progress. The artful manager wants to complete the project in time, but not too early. In innovative work, finishing too soon risks leaving opportunity unexplored and perhaps missing that killer app or feature that makes all the (commercial) difference. Here, good management consists in a careful blend of planning and preparation: planning to bring all the elements of a complex project together in the proper order and at just the right moment; preparation to cope with all the vagaries and emergencies such a process will not fail to present.

An Inclination to “Collect” Things

The writer, crouched in the corner scribbling in his notebook, is a familiar denizen of fiction and report. No telling what she is jotting down, and she herself has no idea where or when she will put this item in a book or poem. Artists tend to collect ideas, impressions, and materials at random on the basis of a kind of freestanding interesting-ness. Almost every studio we have toured has piles and shelves filled with random stuff. “Well, it might come in handy someday.” This is true as well, to a greater or lesser extent, of design firms, product development organizations, and other groups that businesses count on to innovate. This way of collecting is different from the prevailing notion of saving valuable “content” that we find at work in most business activities, one that focuses on efficient storage and retrieval for the purpose of “reusing” things in specific ways. A reuse ethic aims to prevent companies from “rein-venting the wheel.” Artful collection, intended to stimulate invention, is about keeping things that will inspire new thoughts, not applying already developed thoughts. Interestingly, artful collection avoids too-efficient organization of materials because artful collectors value the experience of searching through many interesting things on the way to finding something that they are looking for. Some innovators have told us about finding something valuable while they are looking for something else. In fact, they may never locate the object of the original search.

A Sophisticated Idea About Relationships With “Customers”

The first level judgment of value in business comes from the market: Do people buy it? This fact leads naturally to the idea of giving customers want they want, which, in turn, leads to seeking out what customers need or want via market surveys, focus groups, and so forth. Despite the inherent appeal of finding out what customers want, then satisfying them by giving it to them, the situation becomes more complicated when we create value with entirely new outcomes.

At Bang & Olufsen, makers of high-end consumer electronic products (telephones, televisions, loudspeakers, etc.), the chief designer specifically avoids customer input. He takes the position that customers only want what they know, and that he designs things they cannot know until he shows them. Customers asked what they want, he suggests, will ask for something that is already on the market or that is a minor extension of something on the market. For some kinds of businesses, this may be just fine. But for Bang & Olufsen, which charges very high prices for very classy products, just satisfying the customer with an incremental improvement will not do. Value criteria based on “what customers want” cannot create anything entirely new. One possible substitute for asking customers, then, might be artistic criteria. Artists create value that arises from how well the interdependent parts fit together, not some external reference such as what the customer said. In innovation processes, we must have some way of working toward value that is not externally determined. Knowledge workers, as we have noted, have a strong tendency to value work and work products for their own sake and for the satisfaction they provide the makers.

For artful, collaborative making, in business or elsewhere, a sense of the work as valuable for its own sake, as worth doing regardless of the eventual outcome, is probably essential. If we do not know the outcome, how can we take satisfaction in it? Only by valuing the process itself will we find satisfaction. In this sense, modern knowledge workers point us back to the past to a time when craft identified and defined a person as a Smith, a Miller, a Fuller, and so on.

Conclusion

The following is a list of some characteristics of an artful sensibility, gathered from research and this discussion. Used as tools to observe and analyze an organization that appears disorganized, these notions can help managers understand the form of the process they are looking at and lead them to suggest steps that a disorganization can take to repair itself:

- Willingness to entertain emergent goals

- Product as an emergent result, not a predetermined goal

- Ability to grok forms large and small

- Recognition that form is based on internal principles, not results

- Emphasis on internal principles of unity and form

- Recognition of a difference between problems and difficulties

- Comfort with difficulties

- Comfort in ambiguity

- Willingness to exploit serendipity

- Understanding that collaboration equals innovation

- Project teams collaborate with each other and with an emerging form

- Willingness of groups to create an ensemble

- Willingness to treat the work as important for its own sake

- Closure as determined by judgment and internal principles

References:

- Adler, N. J. (2006). The arts and leadership: Now that we can do anything, what will we do? Academy of Management Learning and Education, 5(4), 486-499.

- (1997). Poetics (M. Heath, Trans.). New York: Penguin Classics. (Original work published 330 BCE)

- Austin, R., & Devin, L. (2003). Artful making: What managers need to know about how artists work. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

- Austin, R., & O’Donnell, S. (2007). Paul Robertson and the Medici String Quartet (Case No. 607-083). Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing.

- Bolland, R., & Collopy, F. (Eds.). (2004). Managing as designing. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Campbell, D. T. (1960). Blind variation and selective retention in creative thought as in other knowledge processes. Psychological Review, 67, 380-400.

- Cohen, W., & Levinthal, D. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128-152.

- Darso, L. (2004). Artful creation: Learning-tales of arts-in-business. Frederiksberg, Denmark: Smifunslitteratur.

- Drucker, P. (1959). Landmarks of tomorrow. New York: Harper.

- Gratzer, W. (2002). Eurekas and euphorias: The Oxford book of scientific anecdotes. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5, 444-154.

- Guillet de Monthoux, P. (2004). The art firm: Aesthetics management and metaphysical marketing from Wagner to Wilson. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Hackman, J. R. (2002). Leading teams: Setting the stage for great performances. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Pasteur, L. (1954). Inaugural lecture as professor and dean of the faculty of science, University of Lille,

- Douai, France. (December 7, 1854). In H. Peterson (Ed.), A treasury of the world’s great speeches (pp. 469-474). New York: Simon and Schuster. (Original work published 1854)

- Philharmonic Society of Orange County. (2007). New York Philharmonic program notes for October 31, 2006. Retrieved August 27, 2007, from http://www.philharmonicsociety.org/ misc.aspx?i=Notes-for-NYPhil1

- Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York: Free Press.

- Roberts, R. M. (1989). Serendipity: Accidental discoveries in science. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

- Simonton, D. K. (1999). Creativity as blind variation and selective retention: Is the creative process Darwinian? Psychological Inquiry, 10(4), 309-328.

- Strati, A. (1999). Organization and aesthetics. London: Sage.

- Weick, K. (1979). The social psychology of organizing—Topics in social psychology series (2nd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Zander, R., & Zander, B. (1998). The art of possibility: Transforming professional and personal life. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.