This sample Managing Intangible Capital Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Competitive advantage and sustaining and growing the business, depends on the use and development of assets or capital—tangible and intangible. A vast literature exists on the topic of managing the tangible capital but management of the intangible is a recent topic. Competition in the 21st century depends on it. “Intangible assets—patents and know-how, brands, a skilled workforce, strong customer relationships, software, unique processes and organizational designs, and the like—generate most of a company’s growth and shareholder value” (Lev, 2004). In firms like Microsoft, intangibles account for 80 to 90% of the value of the corporation (Crainer, 2000; Lev, 2004).

Capital represents resources or assets—either tangible or intangible—that can be used to produce more capital or wealth. Capital refers to any long-lived asset into which other resources can be invested, with the expectation of a future flow of benefits. The value of the company is the value of all its forms of capital minus its liabilities. Organizations rely on both tangible and intangible forms of capital but have traditionally focused on the tangible—financial (e.g., money and credit) and physical assets (e.g., buildings and equipment). Although intangible resources (e.g., knowledge, skill, and motivation) have clearly been recognized and manipulated informally throughout history, deliberate attention to their role in the organization has only emerged in the past decade. Intellectual capital has been the primary focus, perhaps because of the transformation of the economy from a predominantly production-based to a knowledge-based system. However, a large number of other types of intangible capital have been described in recent research journal articles since then including social, relationship, political, customer, organizational, human structural, process, knowledge market, innovation, and collaborative. This research-paper presents various forms of intangible capital and why their development is important to maintaining competitive. An example using a new product development process illustrates how multiple intangible capitals combine for success product introduction and highlights how even a very few deficits in intangible capital can jeopardize success.

What Is The Issue?

The term capital has connotations that lead people to think automatically of the tangible. Indeed, Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (2007) defines capital as “Material wealth in the form of money or property that is used to produce more wealth.” This stems from a period in time where financial capability—and the assets it could buy—was considered the key to competitive advantage. A company with resources could take greater advantage of new technology, sink money into expanding new markets, and invest heavily in new product development. Indeed, capital is one of the three factors of production in classical economic theory (the others being materials and labor).

The current reality of competitive advantage, however, is that companies compete by creating value for their customer. There is an urgent need to

- deliver more products and services faster, cheaper, and at higher quality;

- sustain and enhance gains—building on achievement to attract, keep, and inspire the best people/talent;

- be the supplier of choice as supplier numbers decline;

- thrive on multiyear contracts with annual price reductions—now generating economy-wide impact; and

- compete and win—anywhere—now and in the future.

Companies focus on differentiating their product or service from competitors by developing a strategy that leverages their strengths and targets their particular market niches. This differentiation occurs in one or more of the following three areas: quality, cost, and time. Quality encompasses the customer’s entire experience with a product and includes innovativeness, durability, desired features, characteristics, and postsales service. Cost includes the life cycle costs from supplier, production and distribution costs, and customer maintenance and disposal costs. Time involves time-to-market of new products, availability, and time through the production and distribution chain. Financial resources alone will not ensure effectively competing in these dimensions. Tangible capital alone will not help companies to compete successfully. Succeeding in these dimensions requires an intimate knowledge of processes and their interactions with other parts of the value chain. Excelling in these areas absolutely requires resources beyond monetary capital—it hinges on developing and leveraging another type of capital—intangible capital.

What Forms Does The Intangible Take?

A business (any business) is composed of nothing but processes. Management is responsible for process definition, tracking, and improvement. Most managers fail to understand this concept and instead rely on firefighting. (Hafey, 2007, slide 262)

The firefighting behavior just described is all too common in companies under intense pressure and starved for resources. It reflects a philosophy of “reaction” rather than “proaction.” It is survivalist and is not a winning strategy. To understand the role of management better as proaction, we need to go back to the basics of the work. The definition of work is “the physical or mental effort or activity directed toward the production or accomplishment of something” (Free Dictionary, 2007). Note that work can be physical or mental and that work changes something from one condition to another. The goal of business is to transform raw materials into a valuable product or service. This transformation is work—the conversion of material, talent, and knowledge through physical and mental effort to produce a product deemed valuable by the customer.

Work is physical or mental, but it is seldom purely one or the other. There are three types of work: physical, administrative, and knowledge. Physical is the mechanical “doing” such as repairing machines, building a house, or performing surgery, and it requires a greater degree of physical effort. Administrative work includes the support processes such as processing purchase requests or executing personnel actions, and it requires physical effort to a lesser degree. Knowledge work is the thinking process required to change data and information from one condition to another. Examples of knowledge work include program management, engineering, and planning—these require the least amount of physical work but the greatest amount of mental work.

Managing work involves managing the conversion process—whether it is the physical transformation of material into product or the conversion of data and information into knowledge and processes. The conversion process is the key to profitable performance and the key to differentiating one company, department, or program from another. Each company strives to imprint its unique contribution through excellence in the conversion process.

The management initiative that revolves around the belief that all work is done in processes is lean thinking. The foundation for lean thinking is the understanding that value is determined by the recipient of the output of work processes—customers inside and outside the organization. Lean thinking consists of five principles—value, value stream, flow and pull, empowerment, and perfection—all of which guide decisions to improve flow while producing a quality product on time (Womack, 1996).

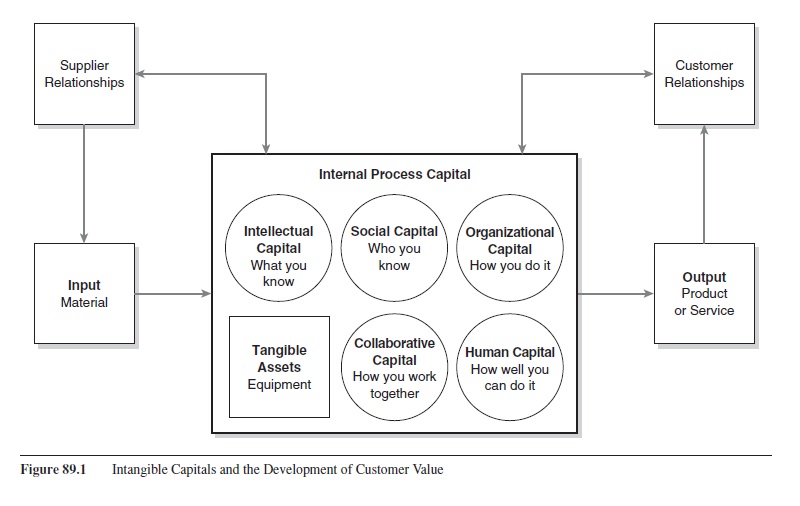

If management of processes is the core of business, where do intangible assets fit? Figure 89.1 presents the classic input-process-output model and depicts five intangible forms of capital as integral to an overarching concept called process capital. Process capital involves both internal and external assets of the organization. Before intangible capital can be managed, we must first look at the various categories of intangible capital and at how they interact to convert material and data into valued customer product and services.

The diagram in Figure 89.1 shows key processes and key forms of the company’s assets. The diagram as a whole represents the conversion process as the key intangible. Inputs including materials, money, equipment, ideas, information, energy, and vision are transformed into outputs that customers value (outputs that are not valued are waste). Process capital is the key to organizational effectiveness. The way assets are used, grown, stored, and combined determines how much value is produced.

Intellectual Capital

Assessing, developing, and protecting the intangible assets is critical to the viability of the company. For example, voluntary and involuntary turnover represents intellectual assets walking out the door. When AT&T layed off 40,000 employees in 1996, they lost an estimated 4 to 8 billion dollars in intellectual capital—equivalent to destroying one third of the physical assets of the organization (Stewart, 1997). Some writers have argued that intellectual capital is the key to intangibles, whereas others have argued that social capital is the key. Certainly, they are intertwined, since a great idea has no value if no one is interested in it.

Figure 89.1 Intangible Capitals and the Development of Customer Value

Figure 89.1 Intangible Capitals and the Development of Customer Value

Intellectual capital represents knowledge but that comes in many forms and its value depends on many factors. Knowledge may be what an individual knows or a routine in the organization that has evolved through practice over a long period. It includes information in files and computers but also informal lessons learned that are passed on from one person to the next through stories that illustrate how the company operates. Ulrich (1998) wrote that intellectual capital is the product of competence and commitment but others have added terms to his equation including communications, collaboration, and courage (Sage, 2002). This function implies that “knowing what” and “knowing how” are not enough. Knowledge must be shared, and there must be a basis for taking actions and taking intelligent risks with that knowledge. Intellectual capital includes pushing the envelope—creativity and innovation.

Microsoft is a well-known example of a highly innovative and successful firm. Ward (2007) described the intangible assets of Microsoft as including the knowledge and skill of its programmers, the software they write, the licenses through which the software is protected and made available to the marketplace, and the share of the market held by that software. These all result in making Bill Gates the richest person in the country and Microsoft one of its most successful companies.

Intellectual capital is an asset that appreciates under the right conditions. Enabling conditions include a work environment where people have access to information, time to think, comfort in sharing, rewards for discovery, and so forth. “Knowledge is a resource locked in the human mind—creating and sharing it are intangible activities that can neither be supervised nor forced out of people—they only come voluntarily” (Ehin, 2000, p. 10).

Organizational Capital

The how or process of transforming inputs into outputs varies both in type and quality. Outstanding companies have found ways to set up their processes that are unique or that outperform competitors. Phrases like world class, best in class, and best practices describe the quality aspect. Unique organizational design also creates competitive advantage. Examples include Nike, Dell, and Toyota, which are well known companies that found ways to design internal and external processes that provided competitive advantage. When new organizational form succeeds in the marketplace, other companies rush in to copy it. The most copied company in the past decade is probably Toyota. Even though Toyota is a manufacturing company, its processes have been widely copied in many industries including health care, retail, and service, particularly its lean philosophy, but in spite of rigorous efforts to emulate Toyota, U.S. auto manufacturers continue to lose market share. Copying is not enough; adapting someone else’s design innovations may not be enough either. Innovations have to fit the context in which the company operates.

Organizational capital resources include reporting structures, formal and informal planning processes, administrative and management systems, and informal relationships among groups within the firm and between the firm and its environment (Tomer, 1987).

Human Capital

The cost of replacing an employee ranges from one to four times his or her annual salary. The range has to do with the employee’s level of expertise. The higher the skill level is, the more value the employee can add, and therefore, the more difficult replacement becomes. Replacement cost is one way of thinking about human capital, one way to quantity it. Another way to develop human capital is through learning. Employees learn both formally (e.g., training sessions) and informally (e.g., experience and coaching). As they pick up new knowledge, their ability to contribute to the organization grows—they become more valuable assets. The knowledge they develop is usually knowing what to do and knowing how to do it, but knowing and caring why they should do it are also important (Quinn, 1996). Others break the task of developing employee knowledge into three categories: technical, interpersonal, and business. Technical training has typically gotten the biggest share of the budget, but as intangible assets are more valued, training in interpersonal and business knowledge should get more attention.

There are five tools for increasing human competence in a firm, site, business, and plant:

- Buy the competence by hiring new talent.

- Build the competence by investing in employee learning and training.

- Borrow the competence by hiring consultants and forming partnerships with suppliers, customers, and vendors to share knowledge, create new knowledge, and bring in new ways to work.

- Bounce the incompetence by removing those employees who fail to change, learn, and adapt.

- Bind the competence by finding ways to keep the most valuable workers.

Companies need to acquire competent employees, and they need to foster employees who are not only competent but also committed. Employees with too many demands and not enough resources to cope with those demands quickly burn out, become depressed, and lack commitment. A company can build commitment in three ways:

- Reduce demand on employees by prioritizing work, focusing only on critical activities, and streamlining work processes.

- Increase resources by giving employees control over their own work, establishing a vision for the company that creates excitement about work, providing ways for employees to work in teams, creating a culture of fun, compensating workers fairly, sharing information on the company’s longrange strategy, helping employees cope with the demands on their time, providing new technologies, and training workers to use it.

- Turn demands into resources by exploring how company policies may erode commitment, ensuring that new managers and workers are clear about expectations, understanding family commitments, and having employees participate in decision making.

Ulrich (1998) argued that fostering competence and commitment together is the only way a company can ensure the growth of intellectual capital.

Social Capital

The flow of information through the organization is as fundamental to company health as the flow of blood through one’s body. The flow of information is influenced by several factors including formal structure, process, culture, and goals. However, the most central factor in creating value out of the flow of information is relationship between the individuals involved in the work. Contrast people in one organization where competition, suspicion, and fear dominate, so information is hoarded with people in another organization where trust, open mindedness, and sharing dominate. The second organization has an intangible competitive advantage that is often called social capital.

“SC (social capital) refers to features of social organizations such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” (Cohen & Prusak, 2001, p. 3). The effectiveness of the network depends on who talks to whom about what and in what style. The relationships can be informational, personal, emotional, or a combination.

Social capital is present in any sharing situation including the grapevine, a community of practice, a learning community, chats at the “watercooler,” a “good-old-boys” network, and so forth. Social networks are webs of relationships where each person is a node or knot in the web and the relationships are links. The information travels from one node or person to another over the links. Social capital could be considered the total health of the network or the combined capacity of the links. The capacity of links depends on trust more than on anything else. Trust means the people in the network believe they can depend on each other to do their share, be prepared and knowledgeable, make a reasonable effort, keep confidences, share accurately and fully what is important to the situation, provide honest and constructive feedback, and willingly contribute to each other’s success. Trust is close to zero in a company that bases operations on fear. For example, consistency in applying policies and public disclosure of policies and practices creates a stable environment that engenders trust, which then increases social capital and thereby increases flexibility and adaptability of the organization. Organizations benefit from this development, realizing the efficiency of reduced turnover and increased openness to change, which results from heightened job security (Leana & Van Buren, 1999). Together, organizational stability and shared understanding provide a greater coherence of organizational action (Adler & Kwon ,2002).

Trust, social capital, and healthy networks emerge over time. They are intangible but critical elements of an effective organization. High levels of social capital are associated with longer job tenure and higher trust, affect the adoption of flexible work practices, and promote innovation (Leana & Van Buren, 1999). The more an organization depends on the creativity and collaboration of employees, the more instrumental levels of trust are to achieving organizational success (Adler & Kwon, 2002).

Collaborative Capital

Assets can be hoarded and destroyed or grown and leveraged. For example, when one employee has knowledge that gives some personal advantage, he or she may choose to hoard it to keep the advantage or choose to share it because of the way it adds value to the overall effort. Leveraging of knowledge occurs most often with collaboration—a willingness to share, to support each other, and to build on each other’s efforts. Collaborate capital is a special case of process capital—the resources it takes to work together readily to leverage individual knowledge and ability.

Collaboration occurs in small groups, but the members of those groups may represent a variety of specialties, functions, or companies. Collaboration ranges in scope from a work team to a major joint venture. In each case, the process of interaction is managed in such a way that the assets each individual brings to the work can be accessed and built on by the other members for the benefit of all. The collaborative process enables intellectual capital and social capital to grow. The organizational design creates conditions for collaboration. Each type of capital feeds into the others.

Refer to Figure 89.1 again. This input-process-output model applies to any company delivering any product or service. This is because all processes require input in the form of material and components or data and information. All processes have a customer as well that makes use of the product, service, or reports. This particular model adds feedback loops from both customers and suppliers. These relationships are absolutely critical in order to remain competitive. Company representatives must have intimate knowledge of rapidly changing customer requirements in order to retain current customers and attract new customers. Company representatives must also have great rapport with suppliers in order to stay abreast of the most innovative materials and processes, as well to negotiate great prices and delivery terms.

As mentioned earlier, several forms of intangible capital, combined with tangible assets, together apply value by transforming inputs to a valuable output. Whereas any tangible asset can produce a product, without expert knowledge concerning how to make the product appealing to customers, the company will fail to thrive and, indeed, may dissolve. For example, a company may have a winning product idea, but does not.

Why Manage The Intangible?

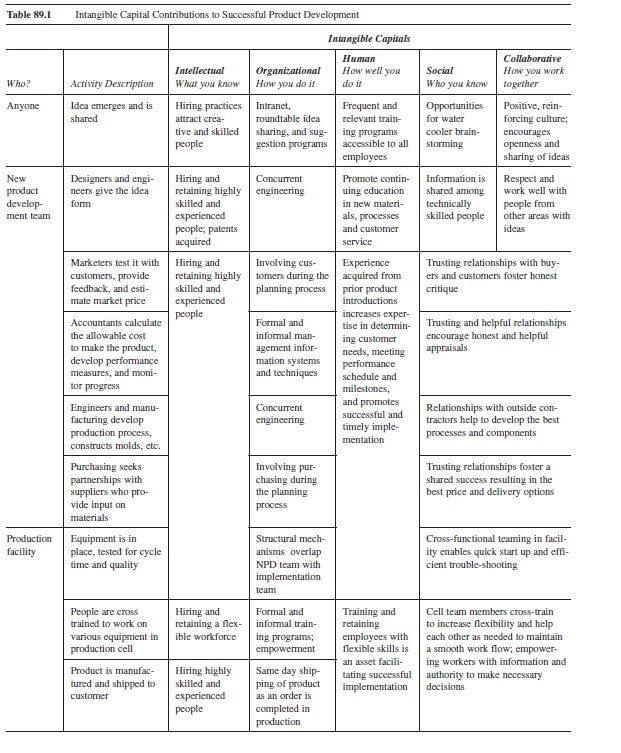

All five of these intangible capitals work together to enable an organization to hire and keep competent employees, foster a creative and innovative culture, and develop the infrastructure necessary to support and maintain a world class organization that consistently outperforms its competitors. The development and rollout of a new product is a good example of a process that touches all parts and functions of a firm. Table 89.1 presents a matrix that describes how each form of intangible capital is integral to each activity from idea generation through development and production of the product.

For example, the first activity in the process is the emergence and sharing of a new product idea. Anyone in the organization may come up with a new product idea and share it with those who can carry that idea forward. Hiring practices attract creative and skilled people capable of generating innovative ideas (intellectual capital). There is an increased probability of capturing that idea if there is a mechanism in place readily accessible to the employee such as a suggestion program or intranet (organizational capital). Providing employees the opportunity to expand their knowledge base and increase their capabilities through relevant and accessible training will foster greater possibility of new ideas emerging in future (human capital). Research indicates that a greater number of ideas are generated in groups and the quality of those ideas increases through discussion. Encouraging both formal and informal opportunities to share and brainstorm encourages these productive interactions (social capital). Finally, an open and positive culture reinforces and may even reward the generating and sharing of new ideas (collaborative capital). Reviewing the other eight activities in the new product development process reveals similar impacts of intangible capital. All of these interactions are essential to a new product development process that generates a great product in a short amount of time that targets customer needs at the right price and manufacturing cost.

Table 89.1 Intangible Capital Contributions to Successful Product Development

Table 89.1 Intangible Capital Contributions to Successful Product Development

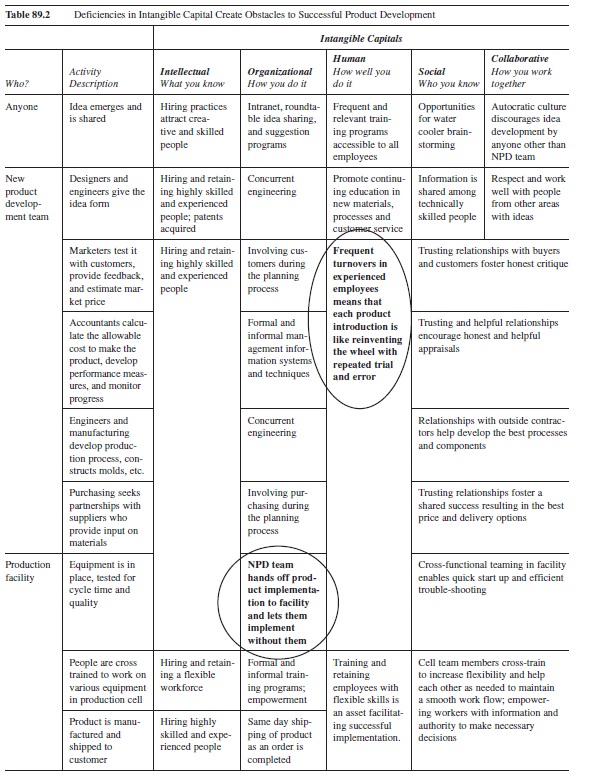

Table 89.2 Deficiencies in Intangible Capital Create Obstacles to Successful Product Development

Table 89.2 Deficiencies in Intangible Capital Create Obstacles to Successful Product Development

But what if any of the intangible capitals are underdeveloped? Table 89.2 presents the same matrix but highlights three different areas where there is a deficiency in an intangible capital. In this scenario, the culture is autocratic and does not solicit participation from all employees (collaborative capital deficiency). As a result, employees stick to the responsibilities of their job and an unknown number of great ideas are lost forever. Consequently, the burden of idea generation falls solely to the product development team and, more specifically, probably the marketing representative.

This autocratic, functional environment permeates the organization and impacts other areas as well. This more stifling culture is not conducive to retaining good employees and results in the loss of experienced personnel (human capital deficiency). The knowledge learned through prior product introductions is lost and this loss makes subsequent new product introductions more difficult and lengthy, riddled with obstacles to overcome. The silo mentality fostered by autocratic cultures is also most likely to cause the bumpy handoff of the new product plan to manufacturing (organizational capital deficiency). Whereas before the development team would assist manufacturing in implementing and rolling out the product, in an environment of individual functions and autocracy, there is a more abrupt handoff that most likely will result in a staggering start-up and possible delayed shipments and cancelled orders.

This example of the negative impact of intangible capital deficiencies on product development extends to all processes within an organization. The three highlighted deficiencies are not isolated, but they would influence the development of other areas of intangible capital as well, creating obstacles throughout all processes.

What Are The Payoffs?

Each form of intangible capital pays off in different ways, although some of the ways look similar and some combinations are possible. The following lists summarize payoffs for each of the five types.

Intellectual capital is both an organizational and an individual asset. The individual can use it to compete for jobs, promotions, and raises and to build relationships that increase his or her social capital. The social network is a critical tool for keeping one’s intellectual capital up to date and for finding opportunities for converting it to tangible assets. The organization embodies its intel-lectual capital in copyrights, patents, products, services, processes, and routines. Organizational intellectual capital is convertible into tangible assets through the sale of products and services and information and into intangibles such as organizational capital through improved ways of organizing and human capital through experts educating new comers.

Social capital is represented by the scope and quality of the network of relationships developed by the company and its members. The network of external relations provides access to information, which helps grow IC, power, and solidarity and which provides a means of strengthening the group’s identity and enhancing its capacity for collective action. In that way, social capital relates to collaborative capital. Improved relationships can compensate for a lack of financial or human capital by “who you know and how you know them.” At the organizational level, social capital is enabling a change in how supply chains work by providing the basis for a shift from contract-based transactions to trust-based transactions which speed up the agreement process and streamline the flow of goods and information. The reputation of the company is another example of social capital that relates to trust and therefore enhances transactions with customers and suppliers. The strength of good relationships shows clearly when contrasting the flow of information between insiders (bonding social capital) in contrast to that with outsiders (bridging social capital). Social capital is a characteristic of a relationship, so if either person or either organization breaks the trust that has been grown over time, the value of the social capital drops toward zero (Adler & Kwon, 2002).

Rich literatures have developed in the past couple of decades around various aspects of organizational capital (Lawler & Mohrman, 2003). The resource-based theory of the firm, which argues that competitive advantage depends on developing internal core competencies, provides one solid example of theory. Best practices provide an example of practical benchmarking where companies try to learn from each other to build those competencies. In each case, the goal is to improve internal processes by making changes in the way the business is organized. Many types of process improvements have been invented, tested, and shared. The successful ones add efficiency and effectiveness to the organization, which represents organizational capital. The methods evolve over time as new experiments in organizing are tried. For example, a focus on quality several decades ago developed into total quality management, which became continuous improvement that led to lean manufacturing and six sigma—each an evolution in thinking, processes, and tools that enhances organizational capital. The competition is so fierce in some industries that enhancing organizational capital by a few percent can mean the difference between survival and bankruptcy.

No organization is likely to disagree with the statement, “We could get better at how we work together.” However, the spread of the methods for enhancing teamwork and collaboration has been slow. When collaborative capital has been the focus, some remarkable companies have emerged as leaders in their industries. McDonald Douglas’ Long Beach plant that manufactures giant military transport planes was on the verge of closing in 1992 because of customer complaints about poor quality when the members decided to take a radically different approach to organizing—a way based on collaboration. The plant won the Malcolm Baldridge award for quality 5 years later. The work to enhance employee involvement and teamwork has continued since then and spread to the rest of the company (Boeing bought McDonald Douglas in 1997). Development of both organizational and collaborative capital saved that plant.

Summary

All of the forms of capital depend on the expertise of the members in the organization—technical, social, and business skills and competencies—that enable high-quality decisions and high-quality work. New members bring some of that human capital with them and develop more through their years in the organization.

New models for reporting tangible and intangible assets have emerged in the past decade or 2 that include the intangible asset monitor (Sveiby, 1997), the balanced scorecard (Kaplan & Norton, 1992, 1996), the Skandia value scheme (Edvinsson, 1997; Edvinsson & Malone, 1997), and the intellectual capital accounts (Danish Agency for Trade and Industry [DATI] 1998). Each of these approaches attempts to include both categories of assets but is based on different assumptions and comes from different frameworks. The balanced scorecard is probably the most influential of these models. It is being adopted and adapted in a wide range of organizations and at both the company and business unit levels including categories for financial, human, customer, and structural capital.

As global competition heats up, it becomes imperative to find ways to develop the many forms of intangible capital. Making them visible via reporting mechanisms is a good first step in highlighting progress-developing capitals in key arenas. It also increases awareness of the impact of deficiencies through either voluntary or involuntary terminations.

The importance of making the intangible forms of capital visible is most readily seen when companies downsize. Firing employees reduces many of the forms of intangible capital for short-term gains in financial capital. When Nortel went through a series of layoffs after the recession of 2000, an article in the Wall Street Journal said the company had finished cutting fat and was not cutting muscle, meaning the loss of people was beginning to weaken the company in obvious ways. The loss of any member diminishes capacity in one way or another because each member has unique intellectual and social capital that walks out the door on the last day of employment. The greater the intellectual capital and social capital is of the person leaving the organization, the greater the loss is to the company. It may be more obvious with top-level employees where a change in executives or leading scientists causes a stock price to plunge, just as the addition of that kind of new person to the company causes its stock to rise. “In a world where a slight advantage easily turns into a leading position, think about the profits a company correctly utilizing all its assets might gain over a company that uses only 20% to 30% of its assets, that is only the financial ones” (J. Roos, G. Roos, Edvinsson, & Dragonetti, 1998, p. 14).

References:

- Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17-40.

- Crainer, S. (2000, November/December). 1 + 1 = 11. Across the Board, 37(10), 29-34.

- Cohen, D., & Prusak, L. (2001). In good company: How social capital makes organizations work. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Danish Agency for Trade and Industry. (1998). Intellectual capital accounts: New tool for companies. Copenhagen, Denmark: DTI Council. Retrieved September 16, 2007, from http:// www.ll-a.fr/intangibles/denmark.htm

- Edvinsson, L. (1997). Developing intellectual capital at Skandia. Long Rang Planning, 30(3), 366-373.

- Edvinsson, L., & Malone, M. S. (1997). Intellectual capital: Realizing your company’s true value by finding its hidden brainpower. New York: Harper Collins.

- Ehin, C. (2000). Unleashing intellectual capital. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Free dictionary. (2007). Retrieved September 16, 2007, from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/work+up

- Hafey, R. (2007). Using “lean leadership” to improve the delivery process. Retrieved September 16, 2007, from http://www .flexco.com/news_events/ppt/NIBA_ApplingLeantoAnyPro cess2.ppt

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard: Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, 70(1), 71-79.

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). Linking the balanced scorecard to strategy. California Management Review, 39(1), 53-79.

- Lawler E. E., & Mohrman, S. A. (2003). Creating a strategic human resources organization: An assessment of trends and new directions. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Leana, C., & Van Buren, H. (1999). Organizational social capital and employment relations. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 538-555.

- Lev, B. (2004). Sharpening the intangibles edge. Harvard Business Review, 82(6), 109-116.

- Merriam Webster’s collegiate dictionary (11th ed.). (2007). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

- Quinn, J. B. (1996). Leveraging intellect. Academy of Management Executive, 10(3), 7-28.

- Roos, J., Roos, G., Edvinsson, L., & Dragonetti, N. C. (1998). Intellectual capital: Navigating in the new business landscape. New York: New York University Press.

- Sage, A. P. (2002, November 2). Information technology and civil engineering in the 21st century. Information Technology, ASCE Talk, p. 9. Retrieved September 16, 2007, from http:// www.civil.gmu.edu/Misc%20Documents/IT-CE.pdf

- Stewart, T. A. (1997). Intellectual capital: The new wealth of organizations. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing Limited.

- Sveiby, K. E. (1997). The new organisational wealth: Managing and measuring knowledge-based assets. San Francisco: Ber-rett-Koehler.

- Tomer, J. F. (1987). Organizational capital: The path to higher productivity and well-being. New York: Praeger.

- Ulrich, D. (1998). Intellectual capital = competence X commitment. Sloan Management Review, 39(20), 15-26.

- Ward, A. (2007). Arian Ward’s “definition” of intellectual capital and knowledge. Retrieved September 16, 2007, from http:// www.co-i-l.com/coil/knowledge-garden/ic/arianic.shtml

- Womack, J. P. (1996). Lean thinking. In J. P. Womack & D. T. Jones (Eds.), Lean thinking: Banish waste and create wealth in your corporation (pp. 305-311). New York: Simon and Schuster.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.