This sample Cognitive Approaches to Motivation in Education Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Like other free research paper examples, it is not a custom research paper. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our custom writing services and buy a paper on any of the education research paper topics.

Often, educators who learn that research on the study of student motivation exists ask, “How can I motivate my students?” This then presents researchers with the difficult task of explaining that studies about student motivation are derived from complex theories that are deductive in nature, and that this literature is meant to be descriptive rather than prescriptive. Hearing this response, the educator usually has an excellent follow-up question: Why does the research exist if it is not meant to help educators? Typically, only researchers read studies about student motivation and the educators are left without access to this information if they are not familiar with the theories, methodologies, and purposes for conducting the research. The purpose of this research-paper is to make some of those theories and findings accessible and to summarize the meaning of this research in real educational contexts.

Before discussing the relevance and application of expectancy-value theory, attribution theory, and achievement goal theory, one must first know why these three theories in particular are important to educators. Research has focused on two major aspects of motivation beliefs: control/competence and value. Control beliefs are the students’ perceptions about the likelihood of accomplishing desired outcomes under certain conditions; competence beliefs are the student’s perceptions about his or her capability to accomplish certain tasks (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2006). Value beliefs are the reasons why an individual would want to become or stay engaged in an academic task (Anderman & Wolters, 2006). Expectancy-value theory is a very comprehensive motivational theory in that it incorporates aspects of both competence and value, while attribution theory and achievement goal theory focus mostly on control or competence. All three theories have an important place in interpreting why students are or are not motivated, and they complement each other by offering suggestions for improving motivation and achievement in both research and practical contexts.

This research-paper begins with a brief review of each theory and relevant research in the motivation literature, including ways in which they are similar and different, followed by a summary of how these findings might apply in classroom settings. Other important motivation theories that are reviewed in this text, but are not covered in this research-paper, are affect, interest, and social cognitive theories. Because this research-paper was written with intent to briefly summarize an entire history of motivation research, readers may want to refer to more comprehensive texts for detailed information such as the Handbook of Educational Psychology (e.g., Anderman & Wolters, 2006; Schunk & Zimmerman, 2006) or Motivation in Education: Theory, Research, and Applications (Schunk, Pintrich, & Meece, 2008).

Theories And Research

Can I Learn and Why Do I Learn? Principles of Expectancy-value Theory

To reiterate, expectancy-value theory is a comprehensive motivational theory, and although all three motivational theories incorporate some aspect of competence or control, only expectancy-value theory focuses explicitly on the role of value. Some would argue that because Weiner was a student of Atkinson, the originator of expectancy-value attribution theory contain aspects of value as well as expectancy. Weiner, however, uses Atkinson’s definition of value in his own attributional model, which is more like affect than values defined in modern expectancy-value theory. Because the theory is cognitive in nature, most of the research has capitalized on the beliefs that students have and how these beliefs affect their academic behavior. Less research has been done on other aspects of the theory, such as investigating the student’s social world where these beliefs come from, or exploring the student’s cognitive processes (e.g., students’ perceptions of the social environment or interpretations and attributions of past events) that are necessary for developing these beliefs. Therefore, this summary focuses on aspects of the theory that have empirical support for classroom application. The two main beliefs that are studied most often are students’ expectations for success, or whether they believe they can accomplish an academic task, and students’ valuing of the academic task, or their reasons for choosing to do the task (Schunk et al., 2008).

Expectations for task-specific success are closely tied to students’ perceptions of competence, and research has shown that both expectancy for success and competence beliefs correlate with grades, effort, and persistence (Wigfield, 1994; Wigfield & Eccles, 1992). There are four kinds of values that students might have about a task: utility value, attainment value, intrinsic value, and cost beliefs (Wigfield & Eccles, 1992). Utility value is the usefulness of the task for individuals in terms of their future goals. Attainment value is the importance of doing well on a task. For example, boys might believe that it’s important do to well in math and science because of gender-related expectations. Therefore, they may have high attainment goals for math- and science-related activities because these subjects are central to one’s sense of self as a boy (Wigfield & Eccles, 1992). Intrinsic value is the enjoyment one experiences while engaged in a task. For example, some students really enjoy participating in game-like tasks at school because games tend to make learning fun and meaningful (Bergin, 1999). The final and fourth value associated with expectancy-value theory is cost. Cost beliefs are perceived negative aspects of engaging in the task, and they may cause someone to choose a less desirable task over something more desirable. For example, a student who does homework rather than going over to a friend’s house to play video games has probably acknowledged that completing a homework assignment is associated with less cost (e.g., giving up a social opportunity) than not doing homework. Many students, however, choose not to do their homework because something else (e.g., playing video games) has outweighed the value of completing the assignment. At times, students’ negative affect state prevents them from engaging in academic tasks, particularly if they believe they will probably not succeed at the task (Wigfield & Eccles, 1992).

Some of the most prominent expectancy-value research has concerned changes among children’s perceptions of expectancy and value beliefs at different developmental stages as well as proposed differences between gender and ethnic groups. Remember that competence is closely related to expectancies for success. Children tend to report a significant drop in their self-perceptions of competence and valuing of academic tasks, but are more accurate in reporting their competence and values in junior high and high school than in elementary school (Eccles, 1983; Eccles, Wigfield, & Schiefele, 1998). While some argue that these changes are primarily developmental, either because young children can’t process all the information necessary to understand their true ability levels relative to others (Blumenfeld, Pintrich, Meece, & Wessels, 1982) or because young children are naturally optimistic about their own abilities (Assor & Connell, 1992) and values (Wigfield & Eccles, 1992), others argue that the educational environment (e.g., grades, teacher feedback) plays a bigger role in developmental changes over time.

How do gender and ethnic groups differ with regard to expectancy and value beliefs? Research suggests that boys generally have higher perceptions of ability and tend to value tasks in mathematics and sports, while girls have higher perceptions of ability and tend to value tasks in reading, English, and social activities (Eccles, 1983; Eccles et al., 1998; Wigfield & Eccles, 1992). Interestingly, although there is no available evidence that African American students have lower perceptions of ability relative to Caucasian students, African American students’ perceptions of ability are less likely to predict grades than Caucasian students (Graham, 1994). Additionally, African American, Hispanic American, and European girls tend to nominate high-achieving girls as people they admire and respect compared to African American and Hispanic American boys, who nominate low-achieving boys as people they admire and respect (Graham, Taylor, & Hudley, 1998). Little is known about why or how these different gender and ethnic groups are motivated. It is up to both scholars and educators to fill in these gaps with both theoretical and application-based research to help serve different kinds of students in the classroom.

One aspect of the expectancy-value model that has not been investigated is cognitive processes. Wigfield and Eccles (1992), however, have defined students’ cognitive processes in part by interpretations and attributions for past events. Attribution theory, as developed by Weiner (1985, 1986), explains how students interpret their performance by looking for reasons that can explain success or particularly failure on academic tasks. Therefore, the main questions answered by expectancy-value theory are, Can I learn? and Why do I learn?, and the main question answered by attribution theory is, Why did I fail?

Why Did I Fail? Principles of Attribution Theory

Attribution theory is related to expectancy-value theory in that students’ perceived causes of outcomes (particularly failure, since students are less likely to look for reasons why they were successful) can influence their expectancies for future success. Historically, there have been three motivational dimensions of attribution beliefs that have been examined in education research: (1) the locus dimension, or whether the cause is internal or external to the student; (2) the stability dimension, or how stable the cause is over time; and (3) the controllability dimension, or how controllable a cause is. Although the locus dimension (internal versus external) and controllability dimension (controllable versus uncontrollable) are most related to affective reactions after failure (such as sadness, guilt, or shame), it is the stability dimension of attribution theory that is most linked with expectations for success. When students receive poor grades or negative feedback for their performance, they immediately look for reasons why they did so poorly. Those reasons may contribute to increased or decreased amounts of effort and persistence on future assignments. According to attribution theory, the most adaptive reasons for failure are things that the student can control, are internal, and are unstable. The least adaptive reasons for failure are things that the student cannot control, are external, and are stable. For example, if a student attributes his or her failure to low ability, this is a stable characteristic that may cause less effort or persistence on future assignments. In contrast, if a task is difficult but the student expects future tasks to be less difficult (an unstable characteristic), he or she may try harder and exert more effort on the next related task. It should be mentioned that attributions are sometimes made in instances of success, especially when the success was unexpected, and stability may have the opposite effect on future effort and persistence when searching for causes of success. For example, a student who attributes success to ability (stable) will persist on future tasks, whereas a student who attributes success to how easy the task is (unstable) may not persist on future tasks.

Besides environmental antecedents of attributions such as task difficulty, teacher grades, and task consistency, there are personal factors that also lead to attributions for success and failure. For example, students know that certain events are only causal under certain circumstances, which means causality must follow certain rules if attributions are to occur. Students’ attributions are perceived, and they are sometimes incorrect or inappropriate ways of looking at causes for failure and success. Finally, one’s own personal history of success or failure has a very strong influence over attributional decisions on current and future tasks. Therefore, some students choose attributions that are adaptive, while others choose attributions that are maladaptive because of these personal factors. The good news is that attributions can be changed to be more adaptive if the student receives feedback on how they can make those changes.

Like expectancy-value theory, attribution theory research has also focused on developmental, gender, and ethnic differences in school-aged children. Unlike expectancy-value theory, however, there has also been research on intervention strategies that can help change students’ attributions to be more adaptive, known as attributional retraining. According to Nicholls (1990), very young children (aged 3 to 5 years) do not differentiate ability and effort, ability and difficulty, or ability and luck, whereas older children (aged 9 to 10 years) are able to at least partially differentiate ability from effort, difficulty, and luck. It wouldn’t make much sense for an early childhood educator to try and explain attributional differences to students, but by late elementary school and early middle school, teachers can help their students achieve by influencing their beliefs through attributional retraining. In studies that have used attributional retraining techniques, students were given verbal praise for their ability as opposed to their effort when students were successful (Schunk, 1983, 1984), but were given verbal praise for their effort as opposed to their ability when students had failed (Dweck, 1975). Teachers can use attributional retraining techniques to help students have more adaptive attributions in both success and failure situations. The research on gender and ethnic differences in students’ attribution patterns is less clear than expectancy-value theory (Eccles, 1983; Eccles et al., 1998; Graham, 1994), but more research is needed to find out if there are indeed any differences and why students are different on these dimensions.

How Can I Get What I Want? Principles of Achievement goal theory

Goal orientations are the reasons for engaging in achievement behaviors (Pintrich, 2003). Therefore, goal orientation theory explains the cognitive processes students go through when making decisions about how to reach a desired objective. Dweck’s theory of intelligence explains the type of goal orientation that students adopt (Schunk et al., 2008). Specifically, students with an entity theory of intelligence, who believe that ability is stable, will most likely adopt a performance goal when engaged in a task; performance goals are defined as demonstrating competence, striving to be the best, or seeking recognition for achievement (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). On the contrary, students with an incremental theory of intelligence, who believe that ability is unstable, will most likely adopt a mastery goal when engaged in a task; mastery goals are defined as focusing on learning, developing new skills, or trying something challenging (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). For example, if after receiving negative feedback, it is important for a student to learn the material presented in the next assignment and he or she has an incremental view of intelligence, then his or her goal is associated with mastering the task at hand. Thus, the mastery-oriented student will strive for improvement to learn the material better for the next assignment. But if it is important for the student to get a better grade or do better than peers and he or she has an entity view of intelligence, then this goal is associated with performing well on the task. Thus, the performance-oriented student will strive for a higher grade relative to others for the next assignment.

Additional research has indicated that there may be different types of mastery and performance goals, which may be characterized as either approach or avoid (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996), and that students may have multiple goals operating simultaneously to reach their objective (Barron & Harackiewicz, 2001; Pintrich, 2000). Performance-approach goals can be differentiated from performance-avoid goals in the following way: if a student wishes to best others and look good in comparison to peers by earning a high grade on the next assignment, then the student has performance-approach goals. In contrast, if a student wishes to avoid failure and looking incompetent in front of others by earning a high grade, then this student has a performance-avoid goal. Research has shown performance-avoid goals are associated with lower levels of engagement and achievement (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996; Midgley & Urdan, 1992). The research on performance-approach goals is less clear; some say it is adaptive for earning higher grades (Skaalvik, 1997; Wolters, 2004) while others say it reduces the likelihood of help-seeking (Ryan, Hicks, & Midgley, 1997). Some have argued that students can also have mastery-approach and mastery-avoid goals (Elliot, 1999). For example, a student who wishes to really learn and understand has a mastery-approach focus, but a student who wishes to avoid misunderstanding or complete the task perfectly has a mastery-avoid focus. Optimally, educators would prefer that students have a mastery-approach goal orientation, since educational objectives often focus on what students learn. Those who believe that students can have multiple achievement goals that act simultaneously have found that certain combinations of mastery- and performance-approach goals are more adaptive than others, since educational expectations demand that in addition to learning, students also perform well by achieving good grades in order to be successful (Midgley, Kaplan, & Middleton, 2001; Pintrich, 2000), particularly in middle school and high school where grades and competition are emphasized.

In recent research on achievement goal theory, more attention has been paid to the role of classroom goal structures, or the kinds of goals that teachers have for their students in the classroom. Teachers with a performance-oriented approach to instruction create an external goal structure, emphasizing high test scores, competitive practices, and social comparison of ability. These criteria for success tend to be consistent with the tenets of the No Child Left Behind Act and can lead to more performance-oriented classroom goal structures (Ciani, Summers, & Easter, in press). Teachers with a mastery-oriented approach to instruction focus more on individual development and learning, such as affording students the opportunity to demonstrate new abilities, providing motivational support for learning, and helping students to understand complex topics (Turner et al., 2002). Research suggests that the more performance-oriented students believe their teachers to be, the more performance-oriented the students tend to be themselves. On the other hand, the more mastery-oriented teachers are perceived to be, the more students report themselves as being mastery-oriented (Wolters, 2004). For the most part, a mastery classroom goal structure is associated with positive student outcomes, whereas a performance classroom goal structure is associated with negative or inconsistent outcomes (Turner et al., 2002; Wolters, 2004). According to this research, it is in the best interest of teachers to structure their classrooms using a mastery-goal format. But additional research indicates that students had higher achievement and were more likely to seek help in classes that combined performance and mastery elements in the form of traditional seatwork and group learning tasks (Linnenbrink, 2005).

Theoretical Comparisons

Expectancy-value theory posits attribution as a cognitive process that is crucial to the formation of competence and expectancies. According to Weiner (2000), some of the causal properties of attribution theory map into expectancy beliefs. In particular, Weiner claims that if a cause is stable, then the same outcome will be anticipated again following a success or failure. On the contrary, failure due to unstable factors will not be an indicator of future failure. Therefore, the expectations for success and failure are determined by causal antecedents of one’s attributional beliefs, and it is typically more adaptive for students to adapt unstable attributions following failure than stable attributions.

Like attribution theory, goal orientation theory is also related to expectancy-value theory. Specifically, goals, like expectancy for success and value for tasks, can explain why students engage in cognitive tasks (Eccles & Wig-field, 2002). Although “goals” appear in the contemporary expectancy-value model as a predictor of students’ task values and expectancy beliefs (Wigfield & Eccles, 1992), it refers in this context to what students strive for (e.g., “I want to become a doctor”) as opposed to mastery and performance goals. Wigfield (1994) suggests that these different types of goals can be integrated theoretically by assuming that goals in the form of broader life plans predict expectancies and values, with expectancies and values determining more specific goals in specific achievement situations. For example, a student who wants to become a doctor should have high expectancy for success in biology classes if he or she wants to be successful and have concurrent values associated with courses that have high utility for becoming a doctor. These expectations and values may lead to a combination of mastery (i.e., learning the material) and performance goals (i.e., doing well relative to others) in courses that are relevant to becoming a doctor. Empirically, research indicates that mastery goals are related to greater valuing of academic material (Wolters, Yu, & Pintrich, 1996), and performance goals are related to declines in valuing of academic material (Anderman et al., 2001). Therefore, it is in a teacher’s best interest to help students either become more mastery-oriented by using strategies that enhance a mastery classroom goal structure or value the material students are learning by making tasks more meaningful and interesting.

Although attributions and achievement goals are both popular theories of motivation in the education literature, little recent research has tied them together explicitly (see Ames & Archer, 1988; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Elliott & Dweck, 1988; Nicholls, 1984; Nicholls, Patashnick, & Nolen, 1985, for earlier examples). But there are theoretical links between why a student believes that he or she fails a task and how the student gets what he or she wants from the task (which is how achievement goals are defined here). Recall that Dweck’s model of goal orientation (Dweck & Leggett, 1988) relates to students’ beliefs about intelligence: someone who has an entity theory of intelligence believes intelligence is fixed, and someone who has an incremental theory of intelligence believes intelligence is malleable. It is possible that if a student experiences failure, the attributions may depend on the students’ view of intelligence (a personal factor): a student with an entity view would likely have maladaptive attributions, since fixed intelligence cannot be controlled and is stable, whereas a student with an incremental view may have adaptive attributions since malleable intelligence can be controlled and is unstable.

Applications of Theory in Classroom Settings

Case Example

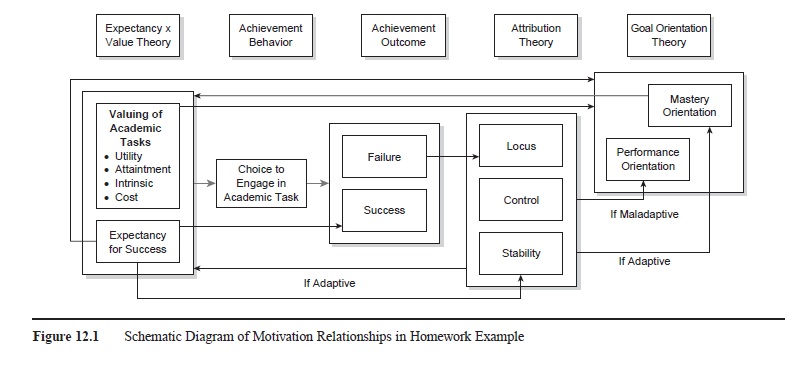

The best way to depict the differences and similarities between expectancy-value theory, attribution theory, and goal orientation theory is an example. Thinking about why children engage in a homework assignment can be examined from multiple dimensions of motivation. Their choice to engage in the homework task initially is usually associated with the value that a student has for homework; in this case it may be utility value. If students believe that they will be successful on their assignment, they will be more likely to exert effort while they are doing homework if they have a high expectation for success (students’ choices for academic activities are determined by their values, and performance on the activity is determined by their expectations for success). Consider what happens when a student receives a graded homework assignment after submitting it the day before and does not get the grade expected (perhaps the student expected an “A” but earned a “D” on the assignment). According to attribution theory, the student immediately looks for reasons for doing so poorly, and those reasons may contribute to increased or decreased amounts of effort and persistence on future homework assignments. In this scenario, the most adaptive reasons for failure are things that the student can control, are internal, and are unstable. After earning the undesired “D” for homework, a student might think about how to do better on the next homework assignment. A student with an incremental view of intelligence, who also feels it is important to learn the material presented in the next assignment, will have goals associated with mastering the task. On the other hand, a student with an entity view of intelligence, who wants to get a better grade or do better than peers, will have a goal associated with performing well on the task at hand. The process of student motivation in this example is represented in Figure 12.1, along with other possible associations between beliefs that have been mentioned previously in this review. This figure is not meant to show causal relationships nor is it a suggested empirical model of how students’ beliefs should be considered. It is merely a schematic diagram of this particular example.

Figure 12.1 Schematic Diagram of Motivation Relationships in Homework Example

Figure 12.1 Schematic Diagram of Motivation Relationships in Homework Example

What Can Teachers Do to Enhance student Motivation?

Most of the research in cognitive approaches to motivation has been mostly correlational in nature and, therefore, is designed to describe current classroom contexts rather than attempt to introduce new motivational strategies in classrooms and examine them experimentally (Urdan & Turner, 2005). Thus, most of the recommendations that researchers make to teachers is based on very general aspects of what they observe in typical classrooms, and they cannot make prescriptive recommendations that claim “this is what works for students.” The recommendations in this section are therefore based on empirical evidence in a very limited sense, and one must assume that what works for some students may not work for all students.

There are many considerations teachers must make before implementing new motivational strategies in the classroom, such as developmental appropriateness of the strategy, prior student achievement, and curriculum goals. As most educators know, the academic expectations placed on junior high and high school students differ from what elementary school children face. Older students are faced with a more structured, competitive environment than younger students, which can cause overall perceptions of abilities and values to change. So what can educators do for students who have low perceptions of ability or decreased value for academic tasks as they progress through the academic system? Some suggestions from Schunk et al. (2008) and Urdan and Turner (2005) include the following: (a) let students know that beliefs about competence can be controlled or changed; (b) decrease the amount of relative ability information that is made public to students; (c) offer reasons for schoolwork than include the importance or utility value of the task; (d) model value in the content of the lesson; (e) activate personal interest through opportunities for choice; and (f) praise students for their accomplishments. We can think about how these suggestions might apply to help motivate students to do their homework: The teacher should make sure that grades on assignments will not be publicly available, offer good reasons (based on importance and utility) for doing the assignment, and perhaps give students some amount of choice either between assignments or within the same assignment. As most educators know, however, students will often find a way to compare themselves to others if it is important to their sense of self-concept and they have strong attainment value for the task (Summers, Schallert, & Ritter, 2003). Teachers must weigh both classroom factors and students’ personal factors when assessing students’ valuing of academic tasks.

According to Urdan & Turner (2005), there is not much research that explicitly connects teacher behaviors and student motivation in the classroom. The general recommendation for teachers based on the research is to assess students’ attributions for success and failure before and after tasks, and to encourage students via attributional retraining to change any attributions that may diminish their sense of control (Schunk et al., 2008). In the homework example, teachers may want to assess the student’s attributions and offer feedback that is appropriate, accurate, and focused on the unstable, changeable causes for failure that might increase the student’s sense of control over the task.

Some intervention studies have been conducted in the goals research in which teachers who implemented mastery goal strategies in their classrooms saw either no change in their students’ motivation (Ames, 1990) or a slight decrease in performance-approach goals (Ander-man, Maehr, & Midgley, 1999), but nonmastery goal classrooms reported a significant decline in motivation. In general, teachers are advised to make student evaluation private, to emphasize understanding and challenge, and to use cooperative learning strategies (Midgley & Urdan, 1992). One of the specific recommendations made by Schunk et al. (2008) to help increase students’ mastery goal orientation in classrooms is to use heterogeneous cooperative groups to foster peer interaction, because cooperative learning is often associated with increased mastery goals among individual students (see the following for examples: Abrami, Chambers, D’Apollonia, Farrell, & DeSimone, 1992; Battistich, Solomon, & Delucchi, 1993; Nichols & Miller, 1994; Sharan & Shaulov, 1990). The ways in which teachers use collaborative or cooperative learning can vary, and the benefits of group work are specific to the conditions of group-related tasks. For example, Summers (2006) found that students in groups who collectively valued the academic goals of group work were likely to adopt individual motivational strategies associated with performance-avoidance goals over time, despite the fact that increased levels of mastery were expected. Perhaps this was because classroom practices associated with social learning and collaboration may make students more conscious of others’ evaluations, thus leading them to adopt motivational goals of self-protection, or because students in this study were asked to change groups on a regular basis. In any case, cooperative and collaborative learning are excellent strategies to help foster positive academic outcomes as long as they are incorporated correctly and with little chance of social comparison occurring. In our homework example, teachers might ask students to do their homework separately but collaborate on tasks that are based on knowledge acquired from the homework assignment to foster learning, accountability, and peer support.

In addition to group work, other ways in which teachers can foster mastery motivation are suggested by the acronym TARGET, which stands for Task, Authority, Recognition, Grouping, Evaluation, and Time (Epstein, 1989). The recommendations based on the TARGET literature are as follows (Ames, 1990): (1) allow task variation, help students see the relevance of tasks, and keep tasks at a challenging level; (2) offer students the opportunity to take leadership roles in their own learning; (3) recognize and offer specific feedback on student effort, progress, and accomplishments; (4) use small-group work to help students assume more responsibility for learning; (5) keep evaluation practices private to avoid social comparison and focus on individual improvement; and (6) adjust the time required for completing work depending on the nature of the task.

Conclusion

This research-paper provided an overview of three motivational theories—expectancy-value theory, attribution theory, and achievement goal theory—and provided suggestions for classroom application based on the research on these theories. Like most of the literature on student motivation, these suggestions were in no way meant to be prescriptive. Researchers are at a disadvantage in that they do not experience classrooms the way that educators do, but they do understand that there are very complex dynamics at work in classrooms on a day-to-day basis that cannot be parsimoniously applied to one single theory or application. Therefore, it us up to educators to decide how this information applies to any particular student or situation now that the information has been “translated” into a more accessible format. Similarly, teachers can assist researchers by helping them understand more about what works and what doesn’t work based on practical field experience. For example, in recent research on teachers’ motivational practices in classrooms, Turner and Christensen (2007) documented a process by which they were able to introduce fundamental concepts and implementation strategies from motivation theory to a group of math teachers in a very collaborative way. Researchers and teachers met on a monthly basis to discuss issues and answer questions such as, Where does motivation come from? What hampers students’ motivation in mathematics? What are some obstacles to making changes to current instructional practice? Teachers then tried these suggestions in their classrooms and reported back to the researchers and other teachers about what worked and what did not. Results indicated that the teachers who were able to successfully change their beliefs about motivation and learning were more likely to change instruction to foster student motivation (Turner & Urdan, 2007). Future research could make similar use of intervention methodology by partnering researchers and teachers to inform motivation practices in holistic and meaningful ways.

See also:

Bibliography:

- Abrami, P. C., Chambers, B., D’Apollonia, S., Farrell, M., & DeSimone, S. (1992). Group outcome: The relationship between group learning outcome, attributional style, academic achievement, and self-concept. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 17, 201-210.

- Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1988). Achievement goals in the classroom: Students’ learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 260-267.

- Ames, C. A. (1990, April). The relationship of achievement goals to student motivation in classroom settings. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Boston.

- Anderman, E. M., Eccles, J. S., Yoon, K. S., Roeser, R. W., Wigfield, A., & Blumenfeld, P. (2001). Learning to value math and reading: Individual difference and classroom effects. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26, 76-95.

- Anderman, E. M., Maehr, M. L., & Midgley, C. (1999). Declining motivation after the transition to middle school: Schools can make a difference. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 32, 131-147.

- Anderman, E. M., & Wolters, C. A. (2006). Goals, values, and affect: Influences on student motivation. In P. A. Alexander & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Assor, A., & Connell, J. P. (1992). The validity of students’ self-reports as measures of performance affecting self-appraisals. In D. H. Schunk & J. L. Meece (Eds.), Student perceptions in the classroom (pp. 25-47). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Barron, K., & Harackiewicz, J. (2001). Achievement goals and optimal motivation: Testing multiple goal models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 706-722.

- Battistich, V., Solomon, D., & Delucchi, K. (1993). Interaction processes and student outcomes in cooperative learning groups. The Elementary School Journal, 94, 19-32.

- Bergin, D. (1999). Influences on classroom interest. Educational Psychologist, 34, 87-98.

- Blumenfeld, P. C., Pintrich, P. R., Meece, J., & Wessels, K. (1982). The formation and role of self-perceptions of ability in the elementary classroom. Elementary School Journal, 82, 401-420.

- Ciani, K. D., Summers, J. J., & Easter, M. A. (in press). A “top-down” analysis of high school teacher motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology.

- Dweck, C. S. (1975). The role of expectations and attributions in the alleviation of learned helplessness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 674-685.

- Dweck, C. S., & Elliott, W. S. (1983). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41, 1040-1048.

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256-273.

- Eccles, J. S. (1983). Expectancies, values and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives (pp. 75-146). San Francisco: Freeman.

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109-132.

- Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., & Schiefele, U. (1998). Motivation to succeed. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social emotional and personality development (5th ed., pp. 1017-1095). New York: Wiley.

- Elliot, A. J. (1999). Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals. Educational Psychologist, 34, 169-189.

- Elliot, A. J., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (1996). Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70, 461-475.

- Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 5-12.

- Epstein, J. (1989). Family structures and student motivation: A developmental perspective. In C. Ames & R. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education (Vol. 3, pp. 259-295). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Graham, S. (1994). Motivation in African Americans. Review of Educational Research, 64, 55-117.

- Graham, S., Taylor, A. Z., & Hudley, C. (1998). Exploring achievement values among ethnic minority early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78, 4-13.

- Linnenbrink, E. A. (2005). The dilemma of performance-approach goals: The use of multiple goal contexts to promote students’ motivation and learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 197-213.

- Midgley, C., Kaplan, A., & Middleton, M. (2001). Performance-approach goals: Good for what, for whom, under what circumstances, and at what cost? Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 77-86.

- Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. (1992). The transition to middle school: Making it a good experience for all students. Middle School Journal, 24, 5-14.

- Nichols, J. D., & Miller, R. B. (1994). Cooperative learning and student motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19, 167-178.

- Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91, 328-346.

- Nicholls, J. G. (1990). What is ability and why are we mindful of it? A developmental perspective. In R. Sternberg & J. Kolligian (Eds.), Competence considered (pp. 11-40). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Nicholls, J. G., Patashnick, M., & Nolen, S. B. (1985). Adolescents’ theories of education. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 683-692.

- Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 544-555.

- Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 667-686.

- Ryan, A. M., Hicks, L., & Midgley, C. (1997). Should I ask for help? The role of motivation and attitude in adolescents’ help-seeking in math class. Journal of Early Adolescence, 17, 152-171.

- Schunk, D. H. (1983). Ability versus effort attributional feedback: Differential effects on self-efficacy and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 75, 848-856.

- Schunk, D. H. (1984). Sequential attributional feedback and children’s achievement behaviors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 1159-1169.

- Schunk, D. H., Pintrich, P. R., & Meece, J. L. (2008). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2006). Competence and control beliefs: Distinguishing the means and the ends. In P. A. Alexander & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Sharan, S., & Shaulov, A. (1990). Cooperative learning, motivation to learn, and academic achievement. In S. Sharan (Ed.), Cooperative learning: Theory and research (pp. 173-202). New York: Praeger.

- Skaalvik, E. M. (1997). Self-enhancing and self-defeating ego orientation: Relations with task and avoidance orientation, achievement, self-perceptions, and anxiety. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 71-81.

- Summers, J. J. (2006). Effects of collaborative learning on individual goal orientations from a socioconstructivist perspective. [Special issue]. Elementary School Journal: The Interpersonal Contexts of Motivation and Learning, 106, 273-290.

- Summers, J. J., Schallert, D. L., & Ritter, P. M. (2003). The role of social comparison in students’ perceptions of ability: An enriched view of academic motivation in middle school students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 28, 510-523.

- Turner, J. C., & Christensen, A. (2007, August). “They just aren’t motivated:” The development and change of teachers’ motivational practices in the classroom. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction, Budapest, Hungary.

- Turner, J. C., Midgley, C., Meyer, D. K., Gheen, M., Anderman, E. A., Kang, Y., et al. (2002). The classroom environment and students’ reports of avoidance strategies in mathematics: A multimethod study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 88-106.

- Turner, J. C., & Urdan, T. (2007, November). Development and change of teacher beliefs and practices in mathematics. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Southwest Consortium for Innovative Psychology in Education, Phoenix, AZ.

- Urdan, T., & Turner, J. C. (2005). Competence motivation in the classroom. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of Competence and Motivation (pp. 297-317). New York: Guilford.

- Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92, 548-573.

- Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Weiner, B. (2000). Intrapersonal and interpersonal theories of motivation from an attributional perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 12, 1-14.

- Wigfield, A. (1994). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation: A developmental perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 6, 49-78.

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (1992). The development of achievement task values: A theoretical analysis. Developmental Review, 12, 265-310.

- Wolters, C. A. (2004). Advancing achievement goal theory: Using goal structures and goal orientations to predict students’ motivation, cognition, and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 236-250.

- Wolters, C. A., Yu, S., L., & Pintrich, P. R. (1996). The relation between goal orientation and students’ motivational beliefs and self-regulated learning. Learning and Individual Differences, 8, 211-238.

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.