This sample Health Systems of Scandinavia Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Health Care And The Scandinavian Welfare States

The three Scandinavian countries – Denmark, Sweden, and Norway – are commonly perceived as quite similar when viewed in a broad international perspective. This similarity relates to their historical background, geographic location, culture, economy, and social structure. Another central characteristic, however, is these countries’ approach to social welfare, in which the central government plays a dominant role in the formation of welfare policies and the public sector is involved extensively in the implementation of such policies. Many observers therefore refer to a Scandinavian model of the welfare state (e.g., Erikson et al., 1987; Pierson, 1991; Ervik and Kuhnle, 1996; Esping-Andersen, 1999). Although there are many specific attributes in each individual country, the characteristics of the Scandinavian welfare state model that they share are a broad scope of social policies, universal social benefits, free or subsidized services, a high proportion of GNP devoted to health and social expenditures, an emphasis on full employment and gender equality, and equal income distribution (e.g., Kautto et al., 2001). Scandinavian health-care systems are intrinsically related to the development of the welfare state, building on the same principles of universalism and equity. Central features have traditionally been an egalitarian ideology promoting equal access to health services, low proportion of cost sharing and a high proportion of tax-based financing to realize these principles, public ownership of hospitals, relatively equal access and a high physician–patient ratio, and decentralized responsibility for health-care services (Kristiansen and Pedersen, 2000).

Defining Characteristics Of The Scandinavian Health-Care Systems

Traditionally, the political culture of the Scandinavian countries has been based on broadly social democratic policies, with health systems built on the principles of universality and equity: all inhabitants have the same access to health services, whatever their social status or geographic location. This strong emphasis on equity has been combined with a tradition of decentralization in which there is regional democratic control of the county and municipal health-care institutions. The municipalities play an important role in providing primary health services (except in Denmark) and various prevention, rehabilitation and health-promotion activities for their inhabitants. This decentralized approach distinguishes the Scandinavian countries from the more centralized tax-based system in the United Kingdom.

The Scandinavian countries belong to the family of integrated single-payer hospital systems. Scandinavian health-care systems are tax-funded health systems with no premium-based financing. Because there is only a minor connection between individual health risks and costs, which are limited to out-of pocket payments, voluntary health insurance has traditionally not played a major role, except as supplementary coverage for services that are not fully covered by the public system, such as eyeglasses and dental care for adults in Denmark. Hospitals are predominantly publicly owned (state or county) and have traditionally been financed through global budget schemes.

Another distinguishing feature of Scandinavian healthcare systems is their governments’ traditional tendency to oppose the expansion of private health-care services. The common understanding has been that health care should be under the control of democratically elected bodies and not subject to commercial market forces. The tradition of voluntary or nonprofit health care in the Scandinavian countries since World War II has been weak, and ‘private’ is therefore usually equated with ‘for profit’ ( vretveit, 2003). A few specialty hospitals are owned by patient organizations, but they are strongly integrated into the public planning system. Fewer than 5% of hospital beds are located in private for-profit hospitals in Scandinavia.

Patients’ rights have been important in the health-care policy debate in Scandinavia, and all three countries have extensive legislation relating to patients’ rights. Another common feature is the introduction of patient choice of hospital in the past decade. In addition, all three countries have introduced waiting time (or treatment) guarantees to address persistent issues of long waiting times. The Danish waiting time guarantee provides access to foreign or private treatment facilities if the expected waiting time at public hospitals exceeds one month (less for life-threatening diseases).

Yet, there are also important differences in the healthcare structures of the respective countries. Far from being uniform, the Scandinavian model is constantly evolving through incremental and more radical change processes. One quite striking difference is related to the organization of health-care services: whereas all three Scandinavian countries have relatively decentralized systems, there are important variations in the number of local authorities and the political and/or administrative level of policymaking. After the Norwegian hospital reform of 2002, the responsibility for primary and specialist health care is divided between the municipalities and the five new health regions, with no role left for the counties. In 2007, Denmark underwent a similar reform that moved responsibility for hospital and primary care services from the counties to five new and larger regions. Sweden is considering some type of structural reform, but has so far maintained county-level health-care institutions.

Another intra-Scandinavian variation relates to the financing of specialized health services. Whereas Norway since 1997 has used activity-based financing with a relatively high share of diagnosis-related group (DRG) compensation, the other two countries employ combination models predominantly based on frame budgeting and a smaller degree of DRG/activity-based funding. Sweden also stands out from the other Scandinavian countries because of its willingness to experiment with purchaser provider models in the health-care sector. In Sweden and Denmark the municipalities typically are relatively autonomous in terms of taxation authority, implying that the correspondence between the local population’s financial contributions and the services offered is higher in those countries.

Governance And Formal Responsibility For The Provision Of Health Services

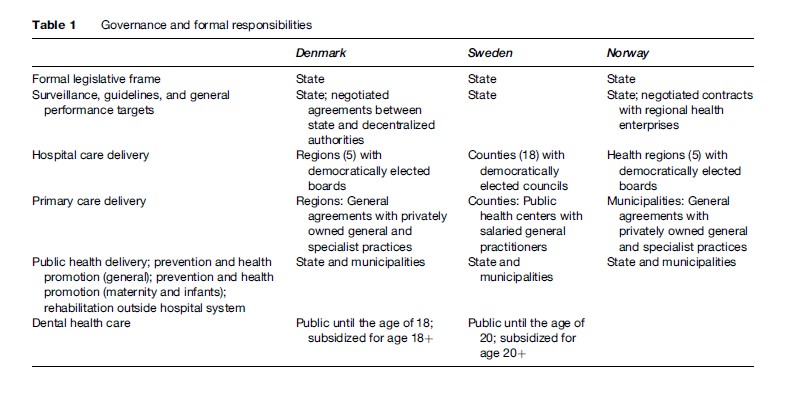

Governance takes place at the municipality and regional level, but within nationally set rules and guidelines (see Table 1). There are institutionalized forums for negotiation between decentralized authorities and the state. In Denmark this negotiation takes place annually as part of the budget negotiations for the municipalities and regions. The Associations of Municipalities and Regions enter into agreements on behalf of their members, although they do not have legally binding means of sanctioning the agreements. The state may sanction agreements by withholding block grants or by legislative intervention. However, in most cases the decentralized institutions follow the agreements. The agreements specify the economic frame, the average taxation rate at the decentralized level, and details of organizational initiatives and programs.

Similar although less institutionalized mechanisms for coordination of policies between the central and the decentralized authorities exist in Sweden, although the Swedish counties have a relatively large degree of autonomy, which has resulted in different organizational and managerial models across the country. Several Swedish counties have experimented with purchaser-provider splits in different forms.

The Norwegian health regions have a semi-independent status, but the national government can influence them in several important ways. First, the state appoints the members of the regional health management boards. Second, the state can influence the articles of association, steering documents (contracts), and decisions adopted by the regional health management boards. The health ministry has attempted to separate a formal steering dialogue from the more informal arenas of discussion ( Johnsen, 2006). Third, the state finances most hospital activities, and there is a formal assessment and monitoring system – with reports on finances and activities submitted to the ministry. On the one hand, hospitals are part of a command-and-control system hierarchy because the state owns them and can mandate policy. On the other hand, the hospitals have gained more autonomy since healthcare professionals replaced county politicians, and the hospital structure today more closely resembles a corporation than a public administration body. Norwegian regions have the formal autonomy to differ in terms of management models, but so far have chosen very similar models ( Johnsen, 2006).

Ownership

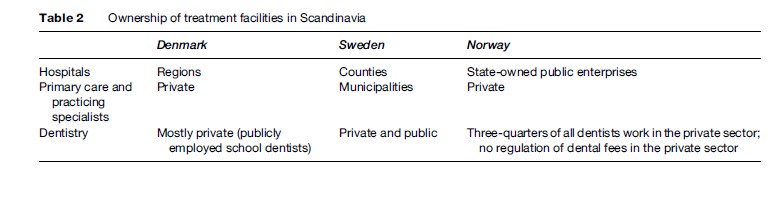

Ownership of hospitals is predominantly public (see Table 2). Until recently most hospitals were owned by the county/region in all three Scandinavian countries. However, the Norwegian reform in 2002 moved ownership to the state level, and the Danish reform of 2007 replaced the counties with five regions that took over the ownership of hospitals. A few specialty hospitals in the three countries are owned by patient organizations and operated on a nonprofit basis.

All three countries have considered organizational forms in the gray zone between public and private management. Sweden has gone furthest in privatizing a major hospital in Stockholm, whereas Denmark and Norway have experimented with various types of public enterprises that have larger degrees of financial and managerial freedom than regular public hospitals. The Norwegian health reform of 2002 formally placed ownership at the state level, but established an enterprise model with five regional authorities and a higher degree of autonomy for hospital managers.

The picture is even more diverse when looking at general and specialist physician practices. Denmark and Norway have a long tradition of private practice, whereas Sweden relies on public health centers staffed by municipally employed health professionals. The status of private practitioners in Denmark and Norway should be seen in the context of the health-care system in those countries. Entry into practice is strongly regulated, and both general practitioners (GPs) and specialists are included in the public planning of services. GPs generally play an important role as gatekeepers to the Scandinavian health systems. Private practitioners also predominantly receive their income through public funding based on centrally negotiated fees. Thus, in terms of planning, fees, and incomes, private practitioners are very integrated into the public system.

Financing And Payment Schemes

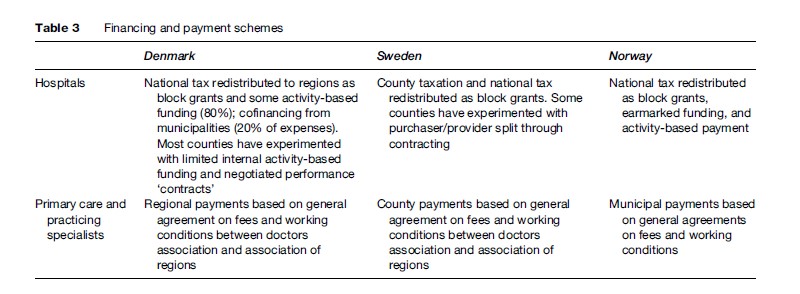

All three countries predominantly rely on public financing of health services (see Table 3). Because of adherence to the overall principles of equity and universal coverage, there is limited user payment for selected services. National taxation is the primary source of funding in Denmark and Norway, whereas Sweden is more decentralized in terms of financing. National funding is redistributed to decentralized authorities in the form of block grants calculated on ‘objective criteria,’ such as population size and composition and activity-based funding. Norway has been most willing to experiment with activity-based financing, whereas some Swedish counties have experimented with purchaser-provider splits starting in the 1990s.

Availability And Utilization Of Traditional Healing Services And Remedies

Complementary and alternative medicine are widely available, but mostly outside the formal health system. There are no indigenous types of medical treatment, but many types of alternative medicine including acupuncture, Ayurveda, and ‘new age’ healing methods have been introduced.

As these services are largely outside the formal health systems, there are few official statistics on the utilization or the size of the market. However, a 2005 Danish national health survey reported that within the past year 22.5% of the Danish population used alternative treatment and 45.2% of all Danes have used alternative treatment at some point in their lives.

Some elements of traditional medicine, such as acupuncture, are now being offered in public health organizations on an experimental basis. The Danish government has established a research center for alternative medicine to collect evidence for such treatments (Videns-Og Forskningscenter for Alternativ Behandling; VIFAB). A similar center exists in Norway (Nationalt Forskningssenter innen Komplementær og Alternativ Medicin (NAFKAM)). Several patient organizations in Denmark (e.g., for cancer, and rheumatic diseases) offer advice and referral to alternative treatment options.

Users normally pay direct out-of-pocket payments for services outside the health-care system. There is limited control of the quality and effectiveness of these services because they are outside the system.

Reform Trends

As part of the broader reconsideration of the welfare state, the Danish and Norwegian health-care systems are currently in the midst of substantial structural reform and Sweden is considering such reforms. The region is thus participating in the wave of health-care reforms underway in most Western industrialized countries. This call for reforms has been spurred by several factors. Most important has been the increasing financial burden placed on governments combined with a desire to improve the resource allocation of health services. This development has been paralleled by new public management (NPM) reforms, which emphasize the need to rethink how the public sector organizes and manages itself. In addition, the introduction of new medical technology and therapies, combined with patient and citizen concerns over the access to and quality of health care, have given rise to new demands within health services. Furthermore, health economists have expressed considerable concern about the inefficiency of health services in several Scandinavian countries, given the paucity of evidence of significant improvement in health outcomes despite increasing health spending (e.g., Flood, 2000; Scott, 2001).

In the planned market models of Northern Europe, the challenge has been to generate a degree of autonomous management within the system of public hospitals while at the same time securing uniform access and quality levels across the different treatment facilities. Principal elements in proposed reforms include (1) increased competition between health-care providers combined with the use of incentive-based contracts and (2) a greater degree of patient influence both through increased freedom to choose among different providers and guarantees of receiving elective treatments within certain time limits. Efforts to reorganize the incentive structure for providers have been accompanied by a growing body of regulatory measures.

The most recent National Health Service reforms in the United Kingdom promised a ‘third way’ between the old command-and-control model and the competitive contracting model: by dismantling the internal market, the goal is to shift the emphasis from competition and choice to an emphasis on cooperation. In the Scandinavian countries, the challenges related to cost increases and the insufficient ability of hospitals to absorb patient inflows have led to the introduction of quasi-market mechanisms, such as waiting list guarantees, patients’ rights to free choice of hospitals, and activity-based funding schemes combined with other NPM-inspired reforms, as well as increased focus on patient pathways, integrated care, and prevention and health promotion coordinated among different public authorities.

Performance

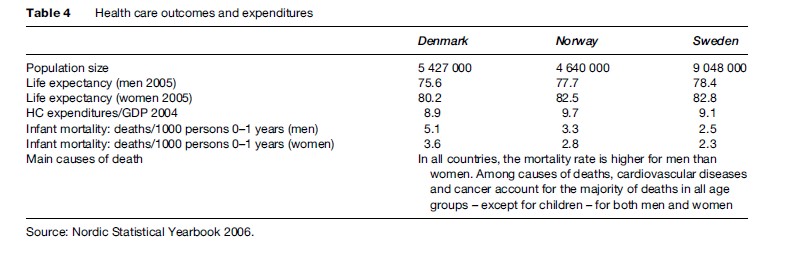

The performance of the Scandinavian health-care model has been the subject of debate (see Table 4). Proponents of the Scandinavian welfare model feel strongly that it has been a great success, referring to it as the ‘most advanced’ and ‘most developed’ stage of the welfare state. Certainly, it is the most comprehensive welfare state in terms of government effort put into welfare provision (Kuhnle, 2000). At the core of the model lie the principles of universalism and broad public participation in various areas of economic and social life, which are intended to promote an equality of the highest of standards rather than an equality of minimal needs. Criticisms have included long waiting lists, excessive bureaucracy, a lack of responsiveness to more fundamental issues about public sector monopsony and/or monopoly in service provision, and a resulting low-quality level. Although the welfare state is highly valued in the Scandinavian countries, observers outside the region sometimes find the Scandinavian approach to be too static in character, with a strong governmental role that deprives the citizenry of important individual freedoms. Other observers praise the egalitarian nature and a degree of security found in the Scandinavian welfare states, but argue that it creates a monotonous uniformity in which the spirit of creativeness and personal initiative has been lost (Erikson et al., 1987).

With the era of strong social democratic dominance of Scandinavian politics seemingly coming to an end and being replaced by the increasing success of the political right, there is a growing awareness inside the Scandinavian countries that there may be other possible welfare providers than the state. This major ideological shift acknowledges that state monopoly of welfare provision may not be optimal, that maximum state-organized welfare is not necessarily an expression of the most progressive welfare policy, that voluntary organizations offer other qualities in welfare provision, that market competition can stimulate both better and more efficient health service delivery, and that the tradition of government-run welfare can undermine individual initiative and threaten economic prosperity (Kuhnle, 2000). The challenge for the Scandinavian health systems will be to integrate such insights while at the same time maintaining the benefits achieved in the public welfare system.

Bibliography:

- Eriksson R, Hansen EJ, Ringen S and Uusitalo H (eds.) (1987) The Scandinavian Model. Welfare States and Welfare Research. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

- Ervik R and Kuhnle S (1996) The Nordic welfare model and the European Union. In: Greve B (ed.) The Scandinavian Model in a Period of Change, pp. 87–110. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Press.

- Esping-Andersen G (1999) Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Flood CM (2000) International Health Care Reform: A Legal, Economic, and Political Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Johnsen JR (2006) Health systems in transition: Norway. WHO Regional Office for Europe on Behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO.

- Kautto M, Fritzell J, Hvinden B, Kvist J and Uusitalo H (eds.) (2001) Nordic Welfare States in the European Context. London: Routledge.

- Kristiansen IS and Pedersen KM (2000) Helsevesenet i de nordiske land – er likhetene større enn ulikhetene? Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association 120: 2023–2029.

- Kuhnle S (2000) The Nordic welfare state in a European context: Dealing with new economic and ideological challenges in the 1990s. European Review 8: 379–398.

- vretveit J (2003) Nordic privatization and private healthcare. International Journal of Health Planning and Management 18: 233–246.

- Pierson C (1991) Beyond the Welfare State? The New Political Economy of Welfare. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Scott C (2001) Public and Private Roles in Health Care Systems. Reform Experience in Seven OECD Countries. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

- Esping-Andersen G (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Furuholmen C and Magnussen J (2000) Health Care Systems in Transition: Norway. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

- Glennga˚ rd AH, Hjalte F, Svensson M, Anell A, and Bankauskaite V (2005) Health systems in transition: Sweden. WHO Regional Office for Europe on Behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO.

- Haug C (2001) Makten flyttes. Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association 18: 2139.

- Hjortsberg C and Ghatnekar O (2001) Health Care Systems in Transition: Sweden. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

- Ja¨ rvelin J (2002) Health Care Systems in Transition: Finland. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

- Lien L (2001) En helsereform uten helseøkonomisk motiv? Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association 18: 21–92.

- OECD (1995) New directions in health policy. Health Policy Studies, No. 7. Paris, France: OECD.

- Pettersen IJ (2004) From bookkeeping to strategic tools? A discussion of the reforms in the Nordic hospital sector. Management Accounting Research 15: 319–335.

- Saltman RB, Bankauskaite V, and Vrangbæk K (2006) Decentralization in Health Care: Strategies and Outcomes. London: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Vallga˚ rda S, Krasnik A, and Vrangbæk K (2001) Health Care Systems in Transition: Denmark. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

- Vrangbaek K (2006) Toward a typology for decentralization and re-centralization. In: Saltman RB, Bankauskaite V and Vrangbæk K (eds.) Decentralization in Health Care: Strategies and Outcomes. London: McGraw-Hill Education.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.