This sample Health Systems of Southeastern Europe Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction To Southeast Europe

Geography

Southeast Europe (SEE) includes the following countries: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia (officially recognized as Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia), Moldova, Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, Slovenia, and Kosovo which was a province of Serbia under UN administration until 17 February, 2008. Slovenia, which was part of the former Yugoslavia, joined the European Union (EU) in May 2004 and therefore is not included in this research paper.

Population And Demographic Trends

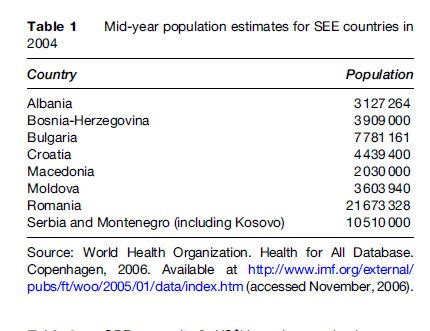

In most SEE countries, the collection of information on population is a clearly defined and standardized procedure. Nevertheless, there are several problems in gathering population data for some countries, due to a high level of internal migration and the presence of internally displaced persons resulting from a 10-year war in the region (Bardehle et al., 2003). Table 1 presents the population estimates for SEE countries in 2004.

In the past decade, the SEE countries have experienced low rates of population growth, except Albania, which continues to exhibit one of the highest growth rates in Europe (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2002a; Council of Europe Development Bank, 2005). In particular, the situation is alarming in Bulgaria, Moldova, and Romania, which have experienced consistently negative population growth rates in the past 10 years (Council of Europe Development Bank, 2005). The decrease in fertility rates and the increase in longevity have resulted in aging of the population in most SEE countries. Thus, the percentage of individuals 65 years and over was 16% of the total population in Bulgaria and Croatia in 2004, the European countries with the highest share of the older age group (Council of Europe Development Bank, 2005).

Economy

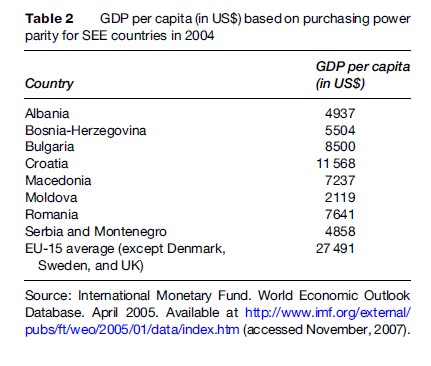

In 1991, after the collapse of communist regimes, SEE countries experienced political turmoil, civil conflicts, and a long-lasting period of socioeconomic transition (Rechel and McKee, 2003). The crisis SEE countries are experiencing reflects socioeconomic upheavals succeeding the disintegration of the socialist economy and penetration of market-oriented mechanisms (Tulchinsky and Varavikova, 1996). In 2004, GDP per capita (in $US) based on purchasing power parity in SEE countries varied from $2119 (in Moldova) to $11 568 (in Croatia), with a remarkable gap between this region and the EU average of $27 491 (Table 2) (Council of Europe Development Bank, 2005).

However, one of the features common to all countries in the region is the rapid growth experienced in recent years. Thus, the annual real GDP growth in SEE has been above 4% since 2001, reflecting a faster growth, on average, than the new EU member states of Central Eastern Europe and the Baltic States (Council of Europe Development Bank, 2005). Furthermore, monetary performance across the region has seen significant improvements in the past few years. In 2004, the average regional inflation rate decreased to approximately 5% from about 25% in 2001 (Council of Europe Development Bank, 2005). Nevertheless, the SEE countries need to increase their reforming efforts and achieve consistent growth rates in order to attain GDP levels and living standards of the more advanced European economies.

Health Indicators In SEE Countries

The health crisis seen in many post-Soviet countries is strongly affecting the SEE region, with high infant and maternal mortality rates and other indicators of poor health status (Tulchinsky and Varavikova, 1996; Roshi and Burazeri, 2002; Rechel and Mckee, 2003). Furthermore, adult mortality rates have increased in most SEE countries in parallel with the disruption of the social security and health-care systems. This raises the need for trained health professionals in the modern context, which was not prepared by the Soviet health-care pattern (Tulchinsky and Varavikova, 2000).

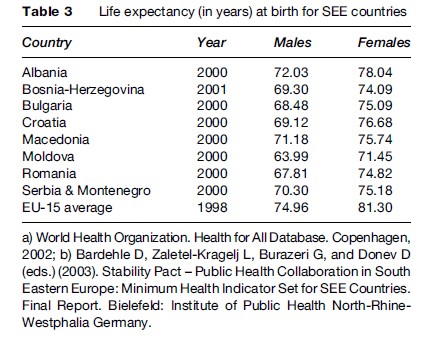

Life expectancy at birth is the most commonly used indicator of population health (Rechel and Mckee, 2003). In both sexes, life expectancy in SEE countries is significantly lower than the EU average (Table 3). Among males, the gap in life expectancy at birth between SEE countries and the EU increased from 5.5 years in 1989 to 7 years in 1999. Within SEE countries, Albania has the highest life expectancy at birth for both sexes, possibly because of the Mediterranean diet rich in fresh fruits, vegetables, and olive oil, which has been suggested as an important factor in keeping rates of coronary heart disease low and hence improving overall life expectancy (Gjonca and Bobak, 1997; Gjonca et al., 1997). Life expectancy is lowest in Moldova, particularly in males (at only 63.99 years in 2000).

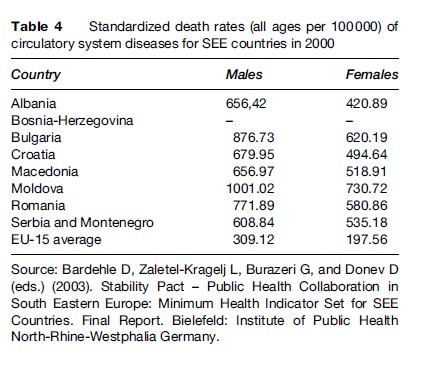

The most common causes of overall death in all SEE countries are cardiovascular diseases – especially among men (Marmot and Bobak, 2000; McKee and Shkolnikov, 2001; Rechel and Mckee, 2003), followed by cancer (Hristova and Dimova, 1997; Jedrychowski et al., 1997; Bray et al., 2000; Situm et al., 2001; Rechel and Mckee, 2003), and then external causes of death (Horton, 1999; Marmot and Bobak, 2000; McKee and Oreskovic, 2002; Mujkic et al., 2002; Rechel and Mckee, 2003), or diseases of the respiratory or digestive system (Marmot and Bobak, 2000; Rechel and Mckee, 2003). As shown in Table 4, in both sexes, standardized death rates of circulatory system diseases are considerably higher than the EU average.

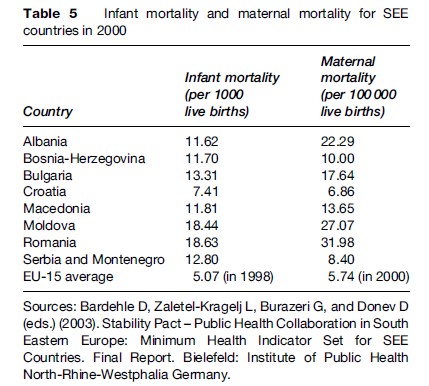

Infant mortality and maternal mortality are particularly high in Romania and Moldova (Table 5) (UNICEF, 2000), countries which also have the highest registered rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs; syphilis and gonorrhea). On the other hand, rates of HIV infection are considered to be low in all SEE countries, notwithstanding the risk of a future epidemic (Rechel and Mckee, 2003). Thus, several underlying factors might fuel the epidemic by fostering an environment that makes people prone to a high level of risk-taking behaviors. Such factors include high mobility, unemployment, poverty, gender inequality, and human trafficking, the latter being particularly prevalent in Albania and Moldova. Commercial sex work has increased tremendously in the past 15 years in Albania, Macedonia, and Moldova, although it is considered illegal in all SEE countries (with the exception of Bulgaria) (Rechel and Mckee, 2003).

Lifestyle Factors

Although there are no established national surveillance systems to asses the major risk factors for chronic diseases, rates of conventional risk factors are thought to be high in all SEE countries (Rechel and Mckee, 2003). The impact of these factors is aggravated by the lack of preventive health services in most SEE countries. All countries in the region display similar patterns of lifestyle and behavioral factors, with very high rates of smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet (with the exception of Albania), lack of physical activity, increasing rates of illicit drug use, and unsafe sexual behavior.

Tobacco

After 1990, the prevalence of smoking increased rapidly in all SEE countries, accounting for a significant proportion of cardiovascular deaths, particularly in middle-aged men (Marmot and Bobak, 2000; Rechel and Mckee, 2003). Furthermore, standardized death rates for lung cancer among men in Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Croatia are thought to be higher than in the European Union (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2001; Rechel and Mckee, 2003). The worst is yet to come given the exceptionally high prevalence rate of smoking in males (Rechel and Mckee, 2003; Ministry of Health of the Republic of Albania, 2004). According to a survey conducted in 1999–2000 in a nationally representative sample aged 15 years and over in Albania, 60% of males and 18% of females reported they were regular smokers (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Albania, 2004). The overall prevalence rate of smoking (39%) maybe the second highest rate among EU members and applicants (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Albania, 2004). Furthermore, smoking has been blamed for the deaths of one in five Albanian males under 70 years (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Albania, 2004).

Alcohol

Events in the Soviet Union in the 1980s led to questioning the conventional wisdom in the West about the cardioprotective effect of alcohol consumption (Chenet et al., 1996). In Moldova, as in other former Soviet countries, there are reports of a close temporal and geographical association between trends in death from CVD and from causes traditionally associated with alcohol consumption (Chenet et al., 1998). In these countries, a significant increase in sudden cardiac death (death within 1 h of onset of symptoms) was noted at weekends (when binge drinking is said to prevail), most marked among young and early middle-aged men (Chenet et al., 1998). Hence, the pattern of drinking, and not only the total amount of alcohol consumed, may have an important impact on the occurrence of sudden cardiac events. A recent systematic review concluded that the association between binge drinking and CVD death meets the standard criteria for causality (Britton and McKee, 2000). While there are no data on binge drinking for Albania, the evidence of an increase in the alcohol-related external causes of death points to an increase in binging mainly among young to middle-aged men (Institute of Statistics of Albania, 2001). Similarities with the Russian drinking style suggest that it is worthwhile assessing the association between binging and fatal cardiac events. Nevertheless, the acute effects of alcohol consumption are less obvious in the other SEE countries. It must be noted that accurate information on the actual consumption of alcohol is difficult to obtain in all SEE countries because of high levels of unrecorded production and consumption. Yet, available data suggest a clear increase in levels of alcohol consumption in most SEE countries, particularly among men (Rechel and Mckee, 2003).

Drugs

After 1990, an increase in the use of illicit drugs was reported in all SEE countries (Rechel and Mckee, 2003). The prevalence of drug use is especially high in young people residing in the capital cities. Demand for treatment of heroin addiction is increasing in all countries, but it remains insufficiently met by medical services (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Albania, 2001). Injecting drug use is associated with an increase in hepatitis C infection, which indicates a risk for a future HIV epidemic in SEE countries.

Nutrition

Healthy eating involves food and nutrition policies, food safety, and micronutrient intake. With the exception of Albania, which has somehow preserved traditional foods of the Mediterranean prototype (in particular, fruits and vegetables) (Gjonca and Bobak, 1997; Gjonca et al., 1997), in most of SEE countries there is an increase in processed westernized foods, high in salt and saturated fats. This nutritional pattern has increased the risk of hypertension and stroke, particularly in Bulgaria and Romania (Dolea et al., 2002; Georgieva et al., 2002). In addition, there is serious concern for the increase in obesity and diabetes rates caused by high calorie intake and low consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables. On the other hand, in Albania, Macedonia, and Kosovo, there is evidence of undernutrition and malnutrition among children and pregnant women (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Albania, 2004). The high prevalence of micronutrient deficiency disorders contributes to high infant and maternal mortality. Deficiencies of iodine, iron (in pregnant women), and vitamin A are considered as major public health problems in these countries (Rechel and Mckee, 2003). Besides micronutrient deficiency, household food insecurity, and improper feeding practices and dietary behavior contribute to malnutrition in both children and women, particularly so in rural areas (Rechel and Mckee, 2003). The nutritional status of children is linked to the economic and social status of their parents, and the situation reported in most countries of the region is likely to reflect growing social inequalities. Children of poorer families or those living in institutions are more likely to show signs of undernutrition (Rechel and Mckee, 2003). Furthermore, one of the factors that contributes to the poor nutritional status of children is the low level and the short duration of breastfeeding (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Albania, 2004).

Physical Activity

Data on physical activity in SEE region are scarce. The available evidence, nevertheless, suggests low levels of leisure time exercise, in all age groups (Ministry of Health of Bulgaria, 2001; WHO/European Commission, 2001; Rechel and Mckee, 2003). The health gains of moderate physical activity are enormous and therefore recent guidelines recommend that all individuals who are not actively employed should engage in at least 30 min of moderately intense exercise every day. This standard is particularly relevant for SEE countries, which are characterized by high levels of unemployment.

Sexual Behavior

SEE today is still a low-HIV-prevalence region, but major concerns exist that since the 1990s there has been an uncontrollable increase in the risk-taking behaviors coupled with spontaneous massive internal and external migration, and a lack of information about the causes and prevention of HIV/AIDS (Rechel and Mckee, 2003). The proportion of heterosexual transmission is increasing in most SEE countries, particularly in Albania where it accounts for 70% of the overall reported HIV cases, (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Albania, 2004). A considerable number of HIV/AIDS cases are among Roma population where risk-taking behaviors are very high according to several surveys conducted in the past few years (Velik-Stefanovska, 2000; Novotny, 2002). The spread of STIs such as syphilis and gonorrhea has raised serious concern, partly because it increases the risk of HIV infection. In principle, all countries have mandatory reporting requirements, but in practice official statistics are considered to be unreliable, in particular because of the growth of private and typically nonreporting physicians (Rechel and Mckee, 2003). Therefore, official figures on the prevalence of STIs in SEE countries should be interpreted with caution.

Health-Care Reforms In SEE

Until 1990, with the exception of Yugoslavia, the health systems in SEE region were based on Semashko’s approach, a centralized system with free-of-charge governmental provision of services. Such a system assured universal coverage to virtually everyone, even to those living in the most remote areas. Prior to 1990, the financing of health care in SEE countries followed the same model as in other socialist countries, with the revenue for health care generated mainly by state resources and minimal out-of-pocket payments limited to purchasing of pharmaceuticals. Health expenditure was determined through a political bargaining process in which the health sector competed with other sectors of the economy (Preker et al., 2002). On the other hand, the health-care system in Yugoslavia was highly decentralized following the principle of local management of health services, in line with the self-management concept that guided the functioning of economic and social sector, including health care (World Bank, 2004; Dzakula et al., 2005). Notwithstanding the advantages of this self-managed health system, the main weak points of the Yugoslavian system as compared to the other SEE countries were the fragmentation and duplication of services, excessive staffing and infrastructure, interregional differences leading to inequities in the amount and quality of care (World Bank, 2004; Donev et al., 2005; Dzakula et al., 2005).

In the early 1990s, changes in the socioeconomic system coupled with large-scale ethnic conflicts and civil turmoil resulted in a collapse of health care in most SEE countries. Particularly, in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, and Kosovo, public health services suffered an almost complete breakdown, leading to an increased number of avoidable deaths. In addition, the difficult transition toward market-oriented economies led to a substantial decrease in health-care financial resources, which was reflected in an outdated health-care infrastructure and equipment as well as underpaid health-care personnel (Rechel et al., 2004).

Following the political and socioeconomic changes in early 1990s, notwithstanding some differences, all SEE countries embarked in similar health-care reforms that, with the exception of former Yugoslavian countries, aimed at shifting away from the centralized command and control state model to a decentralized contracted social health insurance system. The ultimate goal of the governments is to offer high quality health-care services by identifying extra budgetary resources of revenue while maintaining a comprehensive benefits package and financial risk protection against the cost of illness (Preker et al., 2002). On the other hand, in countries of former Yugoslavia, the reform is based on the centralization of decision making, control, and funding of health-care services, and decentralization of the management of local human resources and facilities (World Bank, 2004; Donev et al., 2005; Dzakula et al., 2005).

The health reforms in SEE countries are focusing on the following:

- The change in the role of Ministries of Health from administrative and managerial bodies into policymaking, standard-setting, and quality-assurance institutions;

- Diversification of revenue base by introducing other sources of funding than general taxation, such as social health-insurance premiums and out-of-pocket payments and centralization of all sources of financing in a single pooling and purchasing institution (i.e., Health Insurance Institutes);

- Shifting toward primary health care and health promotion by strengthening public health and primary health-care networks and reinforcing the gatekeeping role of primary care doctors;

- Decentralization of management to local governments and local health authorities;

- Privatization of health care.

These objectives are stated in the current health reform agendas in all the SEE countries.

Health-Care Financing

Health care in SEE countries is financed through a combination of general taxes, payroll taxes in the form of earmarked contributions for health care, out-of-pocket payments classified as formal user charges, private-care payments and informal (under the table) payments, and international aid (Preker et al., 2002). Social health insurance is the main contributor to the total health-care expenditure in Bosnia-Herzegovina (where it contributes to 80% of total spending), Croatia (80%), Romania (78%), and Serbia and Montenegro (94% of general government expenditure on health) (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2000b, 2002; Preker et al., 2002; World Bank, 2004; Donev et al., 2005; Dzakula et al., 2005). General taxation remains the main source of financing health care in Albania (where health insurance accounts for only 11% of total spending in health care) and in Bulgaria (13%) (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2002a, 2003). Moldova is the only SEE country that funds its health-care services only through general and regional taxation and out-of-pocket payments. Although reforms for the establishment of Health Insurance Institute are under way in Moldova, its contribution toward health revenue collection, so far, has been insignificant (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2002c; World Bank, 2003b). Financing of health care through health insurance schemes was introduced in 2004, but the process of implementation, so far, has been very slow (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2002c; World Bank, 2003b).

Health insurance premiums were introduced throughout the 1990s in all SEE countries (except Moldova) and were to be paid by the economically active population. They are deducted at the source and are set at varying levels of net wages across the region. For example, in Albania and Romania these premiums are set at 3.4% and 14% of net wages, respectively, and are equally divided between employees and employers for those employed in the formal sector, whereas for the self-employed the premiums are set at 4–7% and 7%, respectively (Preker et al., 2002). On the other hand, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina are the only two SEE countries that have the highest health insurance premiums (18% and 16%, respectively) (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2002b; World Bank, 2004).

In all SEE countries, the economically inactive population and those engaged in compulsory military service are exempted from health insurance contributions and are covered by transfers from government revenues to the Health Insurance Institutes.

Across the region, health insurance uptake varies considerably between and within countries. Data from the Living Standards Measurement Survey 2002 in Albania revealed that only 39% of the total population had a health insurance license, whereas in Bulgaria this figure is 70% (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2003; World Bank, 2003a). On the other hand, there are remarkable differences within the countries. For example, in Albania people living in urban areas are more likely to have a health insurance license than those living in rural areas (63% vs. 17%, respectively) (World Bank, 2003a).

Out-of-pocket sources of health-care financing come from formal cost sharing, informal payments, and payments to private providers. Co-payments have been introduced in all SEE countries in an attempt to increase revenue for health and contain costs in the health sector. However, formal user charges are minimal and mostly apply to drugs on the essential drug list, certain laboratory and diagnostic procedures, and to those insured individuals who bypass the primary health-care system. Formal user charges applied at health facility level are retained at 50% by health facilities, with the remainder transferred to the Ministry of Health or Health Insurance Institute for use elsewhere in the health system in Albania and Bosnia-Herzegovina, respectively (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2002a, 2002b). Copayments in Croatia contribute to 0.8% of total spending on health. They were introduced to mitigate excessive utilization of services, but under the current pricing structure, co-payments on basic health services are left open-ended, thus presenting a particularly heavy financial burden, especially among beneficiaries with chronic diseases. On the other hand, the broad-based exemptions have effectively reduced the net contributions from those who are able to pay and therefore have undermined the principles of progressivity in contribution according to ability to pay (World Bank, 2004).

Several studies conducted recently show that informal payments (defined as unofficial payments made to healthcare providers for services that are supposed to be provided free of charge to the patients) are common throughout the health systems in SEE countries. According to a study conducted in 2002 in Zagreb, the Croatian capital city, 44% of users of health services reported that they made some forms of informal payments (cash, presents to the doctors, etc.) (World Bank, 2004). A qualitative study carried out in Albania in 2004 revealed that informal payments were particularly pronounced in secondary care where they account for up to 25% of all expenditure on hospital care, whereas in outpatient care they comprise 11% of all expenditure (Partners for Health Reform Plus, 2004). A survey conducted in 1999 in Sofia, the Bulgarian capital city, found that 54% of users of health services made informal payments for state/public health services (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2003).

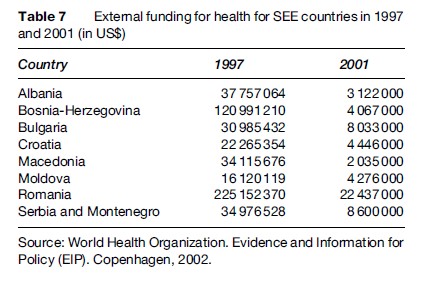

SEE countries have received international financial assistance in the health sector from a range of donors including United Nations agencies, the World Bank, the EU, as well as several bilateral donors.

Launched on the initiative of the European Union in June 1999, the Stability Pact for SEE supports regional cooperation through working tables focusing on democratization and human rights (Working Table I: democratisation and human rights; Working Table II: economic reconstruction, development, and cooperation; Working Table III: security issues) (Rechel and McKee, 2003). Health is addressed as part of the Initiative for Social Cohesion (Working Table II). The expert subgroup for health, under the lead of WHO and Council of Europe, coordinates external resource mobilization and provision of technical assistance to SEE governments with regard to priority setting, reduction in health inequalities, and modernization of legislative and regulatory frameworks (Rechel and McKee, 2003; Bozicevic and Oreskovic, 2004).

External financial contributions to the health sector represent only a small part of total public and private health financing; yet they play a vital role in capacity building and pushing forward health reforms across the region (Rechel and McKee, 2003).

Health-Care Expenditure And Affordability Of Services

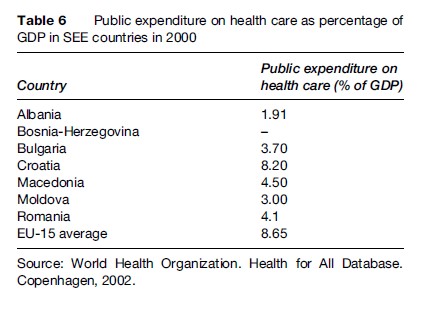

In 2000, SEE governments spent from 1.9% to 8.2% of their GDPs for health care. With the exception of Croatia, public spending on health care in SEE region is not only low when compared to the EU countries in the region, but also when compared to the spending prior to 1990. Table 6 presents public expenditure on health care as percentage of GDP for SEE countries in 2000.

According to estimates from the World Bank, private expenditure on health (defined as formal user charges, payments to private providers, and informal payments) appears to have risen sharply in recent years as public expenditure has fallen. Thus, in 2002, the governmental expenditure in Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, and Moldova comprised only 39%, 50%, 53%, and 58%, respectively, of total health-care expenditure. On the contrary, Croatia, Macedonia, and Romania financed approximately 80% of their total health budget from their public spending (International Labour Office, 2005).

Across the region, the share of health-care spending was 60% higher among poor families compared with rich families. In Albania, Living Standard Measurement Survey 2002 data revealed that health-care spending represented about 80% of the average per capita consumption of a poor family as opposed to 50% paid by the rich. Therefore, poor households are more likely to experience catastrophic health-care expenditure (World Bank, 2003a). The results of a household budget survey conducted in 2001 in Croatia suggested that direct household spending on health-care accounts for about 1.2% of the GDP in this country. When the groups under survey were divided by their social welfare status, it became evident that the pensioners and the disabled were suffering the highest out-of-pocket expenditure, which amounted to 3.5% of their total household expenditure as opposed to only 2.24% for the highest income quintile group (World Bank, 2004).

Although international donors have spent large sums of money in the SEE region, almost none of postemergency resources went to the health-care sector, which remains a low priority for donors. Only a small fraction of the international financial aid was dedicated to the health sector, which in some countries accounted for well below 1% of total external assistance (Rechel and Schwalbe, 2004) (Table 7).

Health-Care Organization

The health-care system in SEE countries is predominantly publicly owned. The Ministries of Health in these countries own and administer most of health-care services.

Public Health Services

The Ministries of Health are the central authorities in public health responsible for setting organizational and functional standards developing and financing national public health programs (such as health promotion and health education, immunization, reproductive health and family planning, screening programs, tuberculosis control, and control and prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infection), collecting data, and reporting on the populations’ health status (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2000, 2002a, 2002b, 2002c, 2003). The district level public health directorates are responsible for covering public health in their districts and are financed by the Ministries of Health. However, public health services are still inadequate in most of SEE countries notwithstanding the increasing need (Rechel and McKee, 2003). The narrow view of public health as merely hygiene and epidemiological services still prevails in public health services in many countries across the region. However, attempts are under way to shift toward modern public health policies in line with the recommendations of WHO and other international agencies (Rechel and McKee, 2003).

Primary Health Care

Strengthening primary health care and the role of family physicians is a common goal all SEE countries are striving for. During the past 10 years, the Ministries of Health have issued several policy papers that place primary health care at the foundation of the reformed health system (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2000, 2002a, 2002b, 2002c, 2003; Rechel and McKee, 2003). As part of these reforms, substantial changes in the organization and financing of primary health care have occurred. Thus, the role of general practitioners as gatekeepers of the health system is being reinforced and contracts between health insurance institutes and general practices have been introduced. General practitioners are found predominantly in the public sector in all SEE countries. Primary health care is provided by health posts and health centers in rural areas, and health centers and polyclinics in urban areas.

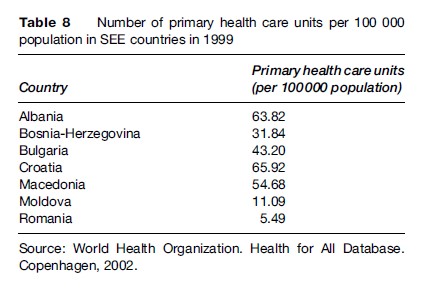

Table 8 presents the number of primary health-care units (per 100 000 population) in SEE countries in 1999 (these units include all health-care facilities providing outpatient care that are staffed with at least one health professional – a physician or a nurse).

Access to secondary care currently requires referral by general practitioners in all SEE countries, but the referral system is frequently bypassed and the frequency of primary health-care consultations has decreased. Thus, Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Macedonia report the lowest values of primary health-care utilization with outpatients contacts per person set at 1.6, 2.7, and 3.0 respectively, compared to an EU average of 6.2.

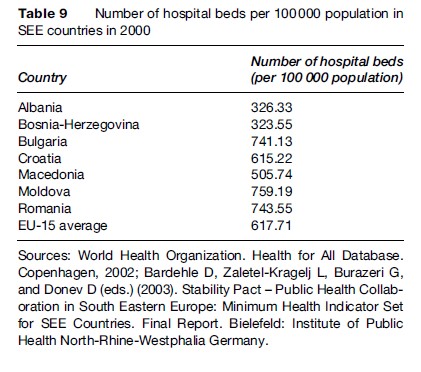

Hospital Care

Secondary and tertiary care is mainly offered in public hospitals. In recent years, the number of hospitals and hospital beds has decreased in most SEE countries, mainly because of inadequate funding from state budgets. Health financing reforms have introduced contracts between hospitals and health insurance funds in order to ensure a higher efficiency of service delivery. Table 9 presents the number of hospital beds (per 100 000 population) in SEE countries in 2000. With the current number of hospital beds, Albania and Bosnia-Herzegovina have one of the lowest rates of hospital beds in Europe (half the average of EU countries and less than half the average of Central and Eastern European countries).

In general, bed occupancy rates in SEE countries are comparable with the EU countries. A survey conducted in Romania in 1998 indicated, however, that the number of hospital admissions was higher than in most of the other European countries, supporting the hypothesis that patients are directly admitted to the hospital without proper referral by the primary health-care system (European Observatory on Health Care Systems, 2000).

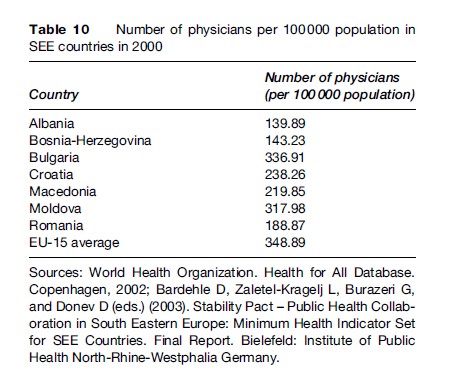

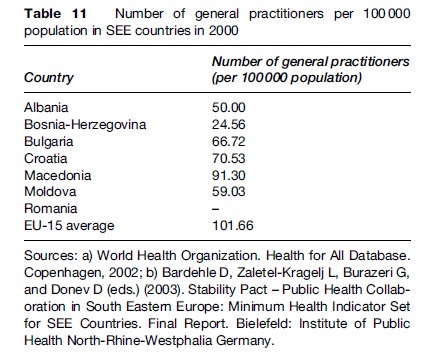

Health-Care Personnel

The number of physicians, general practitioners, and dentists has only slightly changed in most SEE countries from 1990 to 2003, being far below the EU average in most of these countries (Bardehle et al., 2003). In particular, the number of general practitioners is quite low across the region (with exception of Macedonia, which, compared with the other countries in the region, has invested in human resources operating in primary health care). Both the overall number of physicians and the number of general practitioners are the lowest in Albania and Bosnia-Herzegovina, where the need for health-care services and qualified health personnel is continuously increasing. Tables 10 and 11 present the number of physicians and the number of general practitioners per 100 000 population in SEE countries in 2000.

Training Deficit

After 1990, a major challenge for the health workforce in SEE countries has been the shift from a disease-centered model, with emphasis on disease treatment, toward a health-centered model that emphasizes disease prevention and promotion of a healthy lifestyle (Rechel and McKee, 2003; Burazeri et al., 2005). From this point of view, there is actually lack of well-trained public health specialists capable of managing the health problems SEE countries are facing (Laaser, 2002; Burazeri et al., 2005). Traditionally focused on sanitary engineering, most public health specialists in SEE countries lack the capability to solve the emergent multifactorial public health crisis (Tulchinsky and Varavikova, 2000; Burazeri et al., 2005). Therefore, this training deficit of at least one generation of public health specialists has to be resolved by many teaching institutions (departments of public health, institutes of public health and, more recently, schools of public health) in SEE countries in the years to come in order to retrain the public health work force in line with a new task profile of a Western societal type (Laaser, 2002).

However, a new public health training approach has emerged in SEE countries in the past few years. Since 2000, a collaborative network (Public Health Collaboration in South Eastern Europe, a Project of the Stability Pact; Public Health Collaboration in South Eastern Europe, 2007) has the aim of developing a common set of teaching materials and a common database for public health in the region (Kovacic and Laaser, 2001). Furthermore, a minimum indicator set for health monitoring in the region has been developed and practiced in postgraduate teaching programs (Bardehle, 2000; Bardehle et al., 2003). Several training programs with exchange of lecturers and students have been successfully undertaken in various countries of the region (Public Health Collaboration in South Eastern Europe, 2007). The regional coordinating center of this project is the Andrija Stampar School of Public Health, Medical University, Zagreb, Croatia, whereas the international coordinating center is the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Bielefeld, Germany. Participation in this regional network has been rather helpful for the establishment of Schools of Public Health in Albania, Bulgaria, and Serbia, as well as development of the teaching curricula of the Master of Public Health Programs in most countries of the region.

Furthermore, in order to enhance and strengthen the capacity building and development of human resources in SEE, attempts are under way to establish a regional association in public health that would have a synergistic effect and would positively interact with the other regional initiatives already in place.

Conclusion

Following the political changes of 1990 and the region’s orientation toward a market economy, the financing of health-care systems in SEE countries has undergone significant reforms. Nonetheless, health-care reforms in this region have been less firmly addressed compared with other socioeconomic reforms.

Despite several indisputable successes, these have been slow in pace and inefficient in ensuring adequate revenue for health care, in giving appropriate financial incentives to providers and offering qualitative health-care services to consumers. This situation has resulted in widespread informal payments, especially in the big cities across the region. Furthermore, the allocation of funds in some countries (such as Albania or Kosovo), especially in primary health care, seems to be inefficient, with considerable amounts of money allocated to rural health centers and posts with questionable productivity. Also, decentralization efforts that have focused on transferring control over budget allocations from central to local governments have caused severe fragmentation of funds in some countries of the region. A long-term solution should focus on increasing revenue, trying to channel (as much as possible) the informal payments into the public purse, and consolidating the funding in one agency, responsible for purchasing all health services on behalf of the citizens.

Bibliography:

- Bardehle D (2002) Minimum health indicator set for South Eastern Europe. Croatian Medical Journal 43: 170–173.

- Bardehle D, Zaletel-Kragelj L, Burazeri G, and Donev D (eds.) (2003) Stability Pact – Public Health Collaboration in South Eastern Europe: Minimum Health Indicator Set for SEE Countries. Final Report. Bielefeld, Germany: Institute of Public Health North-RhineWestphalia Germany.

- Bozicevic I and Oreskovic S (2004) Looking beyond the new borders: Stability Pact countries of South East Europe and accession and health. In: McKee M, MacLehose L, and Nolte E (eds.) Health Policy and European Union Enlargement. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

- Bray I, Brennan P, and Boffetta P (2000) Projections of alcoholand tobacco-related cancer mortality in Central Europe. International Journal of Cancer 87: 122–128.

- Britton A and McKee M (2000) The relation between alcohol and cardiovascular disease in Eastern Europe: Explaining the paradox. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 54: 328–332.

- Burazeri G, Laaser U, Bjegovic V, and Georgieva L (2005) Regional collaboration in public health training and research in countries of South East Europe. European Journal of Public Health 15: 97–99.

- Chenet L, McKee M, Fulop N, et al. (1996) Changing life expectancy in central Europe: Is there a single reason? Journal of Public Health Medicine 18: 329–336.

- Chenet L, McKee M, Leon D, Shkolnikov V, and Vassin S (1998) Alcohol and cardiovascular mortality in Moscow: New evidence of a causal association. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 52: 772–774.

- Council of Europe Development Bank (2005) Recent Demographic Developments in Europe 2004. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Dolea C, Nolte E, and McKee M (2002) Changing life expectancy in Romania after the transition. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 56: 444–449.

- Donev D, Karadzinska-Bislimovska J, and Spiroski M (2005) National public health strategy in Macedonia. In: Scinite SG and Galan A (eds.) Public Health Strategies: A Tool for Regional Development. Lage, Germany: Hans Jacobs Publishing Company.

- Dzakula A, Sogoric S, Brborovic O, and Voncina L (2005) National health strategy in Croatia 1990–2000. In: Scinite SG and Galan A (eds.) Public Health Strategies: A Tool for Regional Development. Lage, Germany: Hans Jacobs Publishing Company.

- European, Observatory on Health Care Systems (2000) Health Care Systems in Transition: Romania. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

- European Observatory on Health Care Systems (2002a) Health Care Systems in Transition: Albania. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

- European Observatory on Health Care Systems (2002b) Health Care Systems in Transition: Bosnia and Herzegovina. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

- European Observatory on Health Care Systems (2002c) Health Care Systems in Transition: Republic of Moldova. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

- European Observatory on Health Care Systems (2003) Health Care Systems in Transition: Bulgaria. Copenhagen, Denmark: European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

- Georgieva L, Powles J, Genchev G, Salchev P, and Poptodorov G (2002) Bulgarian population in transitional period. Croatian Medical Journal 43: 240–244.

- Gjonca A and Bobak M (1997) Albanian paradox, another example of protective effect of Mediterranean lifestyle? Lancet 350: 1815–1817.

- Gjonca A, Wilson C, and Falkingham J (1997) Paradoxes of health transition in Europe’s poorest country: Albania 1950–1990. Population Development Reviews 23: 585–609.

- Horton R (1999) Croatia and Bosnia: The imprints of war. 1. Consequences. The Lancet 353: 2139–2144.

- Hristova L and Dimova IM (1997) Projected cancer incidence rates in Bulgaria, 1968–2017. International Journal of Epidemiology 26: 469–475.

- Institute of Statistics of Albania (2001) Health Indicators for Years 1994–1998. Tirana: INSTAT.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (2001) Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide, Version 1.0. IARC Press.

- International Labour Office Subregional Office for Central Eastern Europe (2005) Social Security Spending in South Eastern Europe: A Comparative Review. Budapest: International Labour Office.

- Jedrychowski W, Maugeri U, and Bianchi I (1997) Environmental pollution in Central and Eastern European countries: A basis for cancer epidemiology. Reviews on Environmental Health 12: 1–23.

- Kovacic L and Laaser U (2001) Public health training and research collaboration in South Eastern Europe. Medical Archives 55: 13–15.

- Laaser U (2002) The institutionalisation of public health training and health sciences. Proceedings of the international conference on developing new schools of public health. Public Health Reviews 30: 71–95.

- Marmot M and Bobak M (2000) International comparators and poverty and health in Europe. British Medical Journal 321: 1124–1128.

- McKee M and Oreskovic S (2002) Childhood injury: Call for action. Croatian Medical Journal 43: 375–378.

- McKee M and Shkolnikov V (2001) Understanding the toll of premature death among men in Eastern Europe. British Medical Journal 323: 1051–1055.

- Ministry of Health of Bulgaria (2001) National Health Strategy Bulgaria. Sofia, Bulgaria: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Albania (2001) The Albanian National Drug Demand Reduction Strategy for the Period 2001–2004. Tirana: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Albania (2004) Public Health and Health Promotion Strategy: Towards a Healthy Country with Healthy People. Tirana: Ministry of Health.

- Mujkic A, Vuletic G, and Kozaric-Kovacic D (2002) Evaluation of community-based intervention for the protection of children from small arms and explosive devices during the war: Observational study. Croatian Medical Journal 43: 390–395.

- Novotny T (2002) World Bank Southeastern Europe HIV/AIDS Assessment. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Partners for Health Reform Plus (2004) Informal Payments in the Public Health Sector in Albania: A Qualitative Study. Washington, DC: PHRplus.

- Preker A, Jakab M, and Shneider M (2002) Health financing reforms in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. In: Mossialos E, Dixon A, Figueras J and Kutzin J (eds.) Funding Health Care: Options for Europe. European Observatory on Health Care Systems. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Public Health Collaboration in South Eastern Europe (PH-SEE) (2007). A project of the Stability Pact. www.snz.hr/ph-see (accessed November 2007).

- Rechel B and McKee M (2003) Healing the Crisis: A Prescription for Public Health Action in South Eastern Europe. New York: Open Society Institute Press.

- Rechel B and Schwalbe N (2004) Health in South Eastern Europe. Eurohealth 10(3): 6.

- Rechel B, Schwalbe N, and McKee M (2004) Health in South Eastern Europe: A troubled past, an uncertain future. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82: 539–546.

- Roshi E and Burazeri G (2002) Public health training in Albania: Long way towards a school of public health. Croatian Medical Journal 43: 503–507.

- Situm M, Dogas Z, Vujnovic Z, et al. (2001) Increased incidence of colorectal cancer in the Spit-Dalmatia County: Epidemiological Study. Croatian Medical Journal 42: 181–187.

- Tulchinsky TH and Varavikova EA (1996) Addressing the epidemiologic transition in the former Soviet Union: Strategies for health system and public health reform in Russia. American Journal of Public Health 86: 313–320.

- Tulchinsky TH and Varavikova EA (2000) The New Public Health: An Introduction for the 21st Century. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- UNICEF (2000) The Situation of Children and Women in the Republic of Moldova 2000: Assessment and Analysis. Geneva, Switzerland: UNICEF.

- Velik-Stefanovska V (2000) Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia: An Overview of the HIV/AIDS Situation. Geneva, Switzerland, Switzerland: UNICEF.

- World Bank (2003a) Albania: Poverty Assessment. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Bank (2003b) Moldova Health Policy Note: The Health Sector in Transition. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Bank (2004) Croatia Health Finance Study. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Health Organization (2006) Core Health Indicators. Comparison on Core Health Indicator Within WHO Region: Serbia and Montenegro. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization/European Commission (2001) Highlights on Health in Bulgaria. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, European Commission.

- McKee M, MacLehose L and Nolte E (eds.) (2004) Health Policy and European Union Enlargement. European Observatory on Health Care Systems. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

- Mossialos E, Dixon A, Figueras J and Kutzin J (eds.) (2002) Funding Health Care: Options for Europe. European Observatory on Health Care Systems. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.