This sample Imprisonment and Cardiac Risk Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

More than 13 million individuals have a history of incarceration in the USA. In spite of their young age, current and former inmates are at increased risk for developing and dying from cardiovascular disease. In some US studies, current and former inmates have higher rates of hypertension, smoking, diabetes, and end-stage heart disease, compared to the general population and are thus more likely to die from cardiovascular disease.

Why is this the case? There are a number of plausible reasons. Current and former inmates are more likely to be ethnic minorities and poor. Between 50 % and 80 % of US inmates have a history of substance abuse of cardiotoxic agents, like alcohol, cocaine, and amphetamines. Many individuals do not exercise or eat a healthy diet in prison or on the street. And most do not have a primary care provider in the community. The focus of this research paper is to delineate (1) the epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors and disease among individuals with a history of incarceration, (2) to discuss mechanisms for this increased risk, and (3) to describe potential interventions that reduce the risk of disease in this at-risk population. Improving cardiovascular health of individuals with a history of incarceration may lower disease burden in the USA and reduce racial disparities in cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality.

Fundamentals Of Correctional Health Care

Incarceration Is Common And Costly

The prison population has tripled in the past 20 years, and the USA now incarcerates more people per capita than any other nation. Worldwide, imprisonment ranges from 30 people per 100,000/year in India, 119 in China, 148 in the United Kingdom, 628 in Russia, to 750 in the USA (Wamsley 2006). Currently, 2.3 million individuals are incarcerated with an additional 4.6 million on parole or probation, such that one out of every 31 Americans is under the supervision of the criminal justice system (The Pew Center on the States 2009). An additional five million Americans are estimated to have a history of incarceration but are no longer under the criminal justice system jurisdiction (Wilper et al. 2009). In 2008, corrections was the fastest expanding segment of state budgets, with expenditures totaling $44 billion annually. Medical care is one of the principal drivers of cost, totaling $9.9 billion per year (Spaulding et al. 2011). By conservative estimates incarcerating individuals with chronic medical conditions like cardiovascular risk factors and disease by conservative estimates costs two times more than the average inmate.

Definition Of Prison And Jail

Having a history of incarceration can range from a brief stay in jail (facilities that typically house those who are awaiting adjudication or serving sentences of less than 1 year) to longer sentences in prison (which house those who have been sentenced to more than 1 year). The median length of stay in jail is less than 7 days and in prison, 2 years. Despite the range of exposure to the correctional system, there are shared experiences that uniquely define the incarcerated population’s health. To start, prisons and jails are one of the only places in the USA where health care is guaranteed by law. In 1976, the Supreme Court ruled in Estelle v. Gamble that it was “cruel and unusual punishment” not to provide basic health care in correctional facilities. Following the ruling, prisons and jails were mandated to provide acute care services. But as the prison population demographics have changed, health care services have adapted to provide chronic medical care. Between 1995 and 2010, the number of state and federal prisoners aged 55 or older nearly quadrupled (increasing 282 %), while the number of all prisoners grew by less than half (increasing 42 %). There are now 124,400 prisoners aged 55 or older. Many correctional facilities provide individuals their first access as adults to preventive and chronic medical care. An estimated 40 % of inmates are diagnosed with a chronic disease while incarcerated, and 80 % report seeing a medical provider while incarcerated. The correctional health care setting likely influences how ever-incarcerated patients understand their chronic medical condition and how to manage their disease condition.

Quality Of Correctional Health Care

The quality of chronic medical care in correctional health care settings is variable, given limited state budgets or profit motives in privatized prisons. Unlike most free world health systems, which undergo annual quality measurement and public reporting of results, the quality of care within prisons and jails is not subject to government oversight or standardization. Standards of correctional health care are evolving for chronic conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. National organizations such as the National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC) have established guidelines for accrediting prisons and jails, but it is voluntary whether prisons and jails agree to participate. Further, while the NCCHC and organizations like the American Diabetes Association have established screening, diagnosis, and treatment recommendations in prisons and jails, these have not been standardized in jails or prisons. Some prison systems, including Texas, Missouri, and California, have adapted free world measures of quality and have implemented quality improvement projects in the state prison systems (Damberg et al. 2011). For instance, California adopted 79 measures for quality of care, seven of which focus on cardiovascular risk factors and disease. Data on the performance of these prison systems are not publically available. Acute care for chronic medical conditions is typically contracted to outside community hospitals. Only one study has evaluated the quality of care for patients hospitalized with chest pain and found that on average inmate patients with heart disease stay in the hospital longer and receive treatment sooner compared to noninmate patients, indicating that inmates do not receive worse quality hospital care compared to noninmates (Winter 2011).

Transitions Between Correctional And Community Health Systems

Discharge planning does not fall under the constitutional guarantee for health care and nor does health care post-release. Among 33 states surveyed in 2004, all prisons offered some form of discharge planning to a limited number of patients and in most cases only those with HIV disease (Flanagan 2004). Patients with diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease are often released without medications or a follow-up appointment in the community (Mallik-Kane and Visher 2008). Even when provided medications upon release, many do not obtain them. Recently released inmates are less likely to have a primary care physician and disproportionately use the emergency department for health care compared to the general population. In one study, 90 % of individuals released from jail were uninsured or lacked financial resources to pay for their medical care (Conklin et al. 2000). Inmates with health problems may have a harder time returning to the community, as they are additionally confronted with the task of managing their health problems, obtaining health care, and keeping up with medications or appointments, while meeting their basic needs. Many return to the community without financial resources, housing, employment, or family support. And many individuals convicted of drug felonies are released from prison and prohibited from accessing safety net services, including food stamps, public housing, or federal grants for education.

Epidemiology Of Cardiovascular Risk Factors And Disease

Cardiovascular Disease Mortality Cardiovascular disease is one of the top causes of death of inmates in the incarcerated population. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, during the period of 2001–2004, 12,129 state inmates deaths were reported and 27 % of these deaths were attributed to heart disease (Mumola 2007). However, in spite of being a leading cause of death, the risk for death from cardiovascular disease is not higher than what would be expected if they were living in the free world (Spaulding et al. 2011). In contrast, recently released inmates have an increased risk for mortality compared to the general population (Binswanger et al. 2007; Rosen et al. 2008; Spaulding et al. 2011). In a retrospective study of 30,000 individuals released from Washington state prison, recently released inmates had a greater risk of all cause and cardiovascular disease mortality than the general population in the year following release (adjusted HRs 2.1, 95 % CI 1.7–2.6) (Binswanger et al. 2007). Evidence to date suggests that white inmates have an increased risk of dying compared to the general population, whereas blacks do not. A retrospective study of individuals released from North Carolina prison between 1985 and 2000 found that white ex-prisoners had 30 % greater than expected rate of death from diabetes and cardiovascular disease compared to the general population, although no difference was detected among black former inmates (Rosen et al. 2008). A study from Georgia, in which two-thirds of the prison population was black, also found no increased risk of cardiovascular death upon release (Spaulding et al. 2011). Importantly, there have been no national or prospective studies looking at the association between incarceration and cardiovascular disease mortality.

Incarceration Is Associated With Increased Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors

In US studies, current and former inmates have higher rates of hypertension (Wang et al. 2009), smoking (Cropsey et al. 2008), and left ventricular hypertrophy (Wang et al. 2009) than the general population. Analyses comparing diabetes in patients with and without a history of incarceration have yielded conflicting results (Leddy et al. 2009). Other studies have shown higher rates of cardiovascular disease risk factors among current and former inmates, but are based on extrapolations from noninstitutionalized Americans (2002), data from single institutions (Baillargeon et al. 2000), or limited to self-reported health outcomes, (Wilper et al. 2009) which may be subject to detection bias given that health care is constitutionally guaranteed in prison. In spite of these limitations, current and former inmates appear to have increased rates of cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, and smoking.

Mechanisms For Increased Cardiovascular Disease Risk

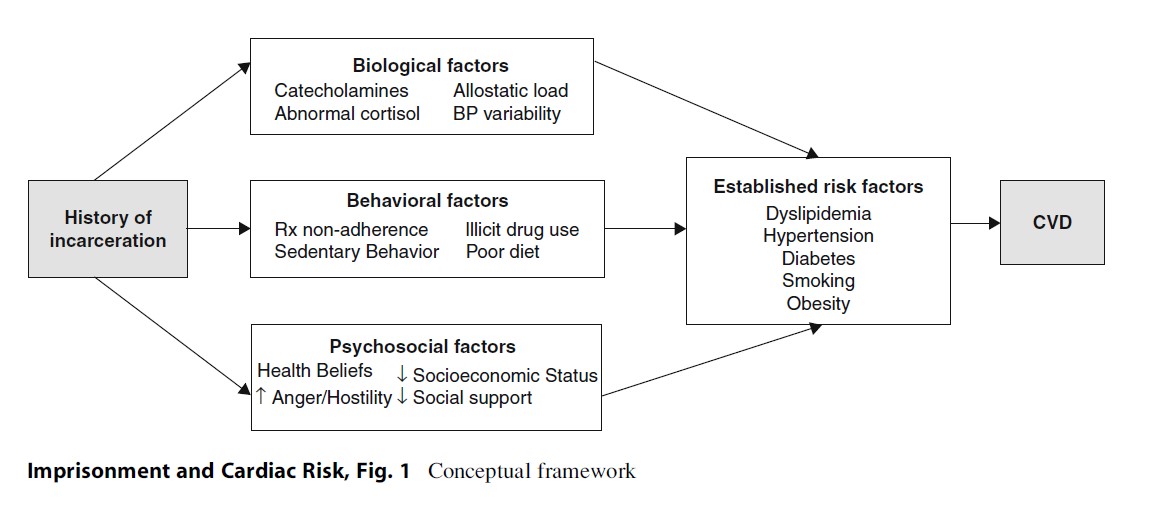

Despite the evidence supporting the association between incarceration and cardiovascular risk factors and disease, it is not known why this association might exist. There are several plausible biological, behavioral, and psychosocial factors through which incarceration may lead to increased cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality. No study has determined which or what combination of these potential mechanisms leads to poor health outcomes (Fig. 1).

Incarceration May Be Associated With Dysregulated Stress Responses

As early as 1971, psychiatrist George Engel published a paper reconstructing the events in the hours before 170 people died and described the sudden death of a gentleman just released from prison as evidence that major stressful life events can lead to sudden cardiac death (Engel 1971). While researchers speculate that current and former inmates may have dysregulated stress mechanisms leading to increased risk for poor health outcomes (Massoglia 2008), no studies have examined the association between incarceration and various markers of stress – dysfunction of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, increased catecholamines, blood pressure reactivity, or physiological responses to chronic stresses, as measured by allostatic load. Alterations in these pathways may lead to cardiovascular disease, as elevated catecholamines have direct effects on the heart, blood vessels, and platelets. Catecholamines and cortisol have been implicated in the development of heart failure and cardiac ischemia. Blood pressure reactivity is associated with hypertension (Matthews et al. 2006). And allostatic load, a measure of cumulative stress burden, has been found to be a mediator for social disparities in cardiovascular disease (Sabbah et al. 2008). However, while life post release is stressful and may lead to dysregulated stress responses, this has not been studied.

Incarceration Is Associated With Behavioral Risk Factors That May Increase Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Higher rates of alcohol abuse and illicit drug use in patients with a history of incarceration are well documented and could contribute to increased cardiovascular risk. Injection drug use is associated with contracting HIV and hepatitis C, both of which are independently associated with developing cardiovascular disease. Whether substance abuse and its medical comorbidities contribute to the observed increased cardiovascular disease in this population is unknown. Epidemiologic studies looking at the association between incarceration and cardiovascular disease risk factors, either include measures of a single substance of abuse (Binswanger et al. 2009), do not explore it at all (Wilper et al. 2009), or find that it does not contribute (Wang et al. 2009).

Similarly understudied are the selfmanagement strategies of current and former inmates – their physical activity, diet, pharmacologic adherence behaviors, and how the correctional system environment and its health care system might affect this. The average prison inmate spends an average of 2 years incarcerated, during which time there are limited opportunities for exercise, choice of diet, and self-management of medications. Limited studies have demonstrated that prison diet can either positively or negatively influence cardiovascular risk (Eves and Gesch 2003). Prison diets (inclusive of inconsistent timing and poor availability of sugar-free or fat-free alternatives) have been identified as a source of cardiovascular disease-related complications in some prisons. Even fewer studies examine the association between physical activity and cardiovascular disease risk factors among incarcerated patients. These studies have found that being in prison is associated with a decrease in physical activity among women (Young et al. 2005) but an increase among men (Leddy et al. 2009). Studies examining body mass index during incarceration have found that inmates who serve shorter sentences had a nonsignificant trend for a reduction in body mass index while those who serve longer sentences have significant increases (Leddy et al. 2009). A study of older inmates reveals that being incarcerated can facilitate developing skills in managing one’s cardiovascular risk factors; however, these skills may not be translatable to managing one’s disease in the community (Loeb et al. 2007). In most correctional settings, patients do not manage their own medications. They do not pick up their medications at a pharmacy, dispense their own medications (for example, inject insulin or learn which medications to take at mealtime), nor develop the skills to manage complications of chronic medical conditions, including using a glucometer or sleep apnea machine. These are all skills that are essential to managing chronic conditions upon release to the community. No studies detail how best to provide chronic disease self-management support in correctional settings around hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, which is a cornerstone of cardiovascular disease risk factor management (Wagner et al. 2001).

Incarceration Is Associated With Psychosocial Factors That May Increase Cardiovascular Risk

Incarceration may augment socioeconomic disadvantage, which is independently associated with the development of cardiovascular disease. Individuals released from prison and jail often face additional barriers to obtaining employment, housing, and public entitlements and encounter various restrictions of their political rights (Travis 2005), which may further impede access to healthcare and medical treatment. Current and former inmates have been found to have higher levels of anger and hostility (Cuomo et al. 2008) which are associated with significant increases in angina, myocardial infarction, and angiographic severity of cardiovascular disease (Iribarren et al. 2000). Those with a history of incarceration may suffer from social isolation (Mallik-Kane and Visher 2008), which has also been linked to higher total mortality independent of cardiovascular risk factors. A related issue is that patients receiving psychotropic medications (e.g., olanzapine) are at increased risk of diabetes and, given the high rates of mental illness among the incarcerated, psychotropic medicine use is more common than in the general community. Another plausible mechanism that has not been studied is current and former inmates’ health beliefs and attitudes about cardiovascular risk factors and disease. Research in minority and vulnerable populations has demonstrated that disparate patient adherence to health-supporting behaviors (exercising, eating a healthy diet, taking medications as directed, avoiding illicit substance abuse) is an important component of racial disparities in cardiovascular outcomes. Given the disproportionate incarceration of poor minority populations, this likely plays a role in the increased risk of cardiovascular risk factors and disease of ever-incarcerated populations.

Future Directions: Interventions To Reduce Cardiovascular Disease Morbidity And Mortality

Previous studies have demonstrated that recently released inmates have an increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease and current and former inmates are likely to have increased rates of cardiovascular risk factors. However, the reasons for this are unclear, making interventions that improve this population’s health difficult to design. As the correctional population continues to age and correctional health care shifts from a focus on acute conditions and infectious diseases to noncommunicable diseases, like cardiovascular disease, important first steps are to understand why current and former inmates have increased rates of cardiovascular risk factors and disease, followed by design of prison and community-based interventions. To achieve this aim, we need more comprehensive studies that include patients with a history of incarceration and the correctional health care system.

Better Studies

Currently incarcerated individuals are not included in national surveys studying cardiovascular risk factors and disease, including the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (Wang and Wildeman 2011). Also, longitudinal cohort studies funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute designed specifically to examine the epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors and disease in minority populations do not follow individuals from the community into the correctional system, thus leading to loss of follow-up among minority populations, in particular black men and, thus, biased estimates of risk and disease. Why is this the case? In 1978, following decades of unethical prison research, the federal government instituted a moratorium on research in correctional settings. Recently, the Institute of Medicine revisited the issue at the behest of the Department of Health and Human Services and released a report on the ethics of conducting research on prisoners. It recommended the continuation of current restrictions but suggested updates to improve prisoners’ ability to participate in limited clinical studies, particularly those with minimal risk and only interventions with demonstrated safety and efficacy. Despite these recommendations, the prohibition on prison research has not been lifted. Currently, individuals who enroll in studies while free may not be followed into prisons and jails (unless the researcher seeks OHRP approval under Subpart C) and in certain jurisdictions cannot be followed even upon release. Under the current guidelines, participants are removed from the study at the time of incarceration, unless specifications are delineated in the initial institutional review board application. Given this barrier, national surveillance systems may provide flawed estimates of cardiovascular risk factors and miss opportunities to understand how incarceration and the correctional health care system affect cardiovascular risk factors and disease. National policies should be created that allow incarcerated individuals to enroll in surveillance studies or continue their participation in a study they enrolled in prior to incarceration. Ever-incarcerated individuals, prison officials, researchers, and ethicists should be included in this dialogue so that such policies are patient-centered and acknowledge the unique logistics of conducting research in prison (or jail) without impeding good science or violating research ethics.

Understanding The Patient’s Experience

Self-management is the cornerstone of treatment for patients at risk for or living with cardiovascular disease. Many studies have shown that a patient’s health beliefs and experiences, medication adherence, or self-care behaviors are associated with improved blood pressure, diabetes, and cholesterol control. We know that individuals who are incarcerated are disproportionately comprised of minority racial groups and individuals from low socioeconomic environments. Additionally, given the established association between racial discrimination and hypertension, the incarcerated population has the added stigma of being incarcerated. How discrimination might impact their health and health care access has not been fleshed out. The determinants of ever-incarcerated individuals’ cardiovascular disease outcomes are likely multifactorial, but their knowledge, attitudes, and health beliefs likely play a significant role and are shaped by the correctional health setting. Specific attention should be paid to studying the health knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of ever-incarcerated individuals and how prison environmental issues, including access to healthy foods and health care in prison and upon release, affect self-efficacy for managing health in prison and upon release.

Include The Prison System

Given that around 60 % of inmates return back to prison within 3 years, understanding how the correctional health care system delivers care for individuals with cardiovascular risk factors and disease and particularly transitions of care are crucial to reducing cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in this population. A framework to improve the delivery of chronic care in the correctional system must be applied to study and improve care in the correctional setting. One such model, the Chronic Care Model, has already been applied in California (Wagner et al. 2001). The Chronic Care Model is a patient-centered model of care that identifies the essential elements of a health care system that encourages high-quality chronic disease care. These elements include the community, the health care system, self-management support, delivery system design, decision support, and clinical information systems. Redesigning systems of community primary care to the Chronic Care Model has led to improvements in health care outcomes for individuals with cardiovascular diseases. Adapting this model and appropriate metrics for assessing care delivery in correctional settings are underway and should incorporate corrections-specific needs (including security, transfers, and lock-downs) and the realities of the state of correctional medicine including the lack of robust informational technologies (Ha and Robinson 2011). These efforts will generate hypotheses about how prison health care, particularly self-management support and discharge planning, might impact inmates’ long-term control of cardiovascular risk factors and management of disease. Moreover, current initiatives to improve quality of care in the correctional system should be mandated and overseen by state and local government entities, given that taxpayers pay for care behind bars. These initiatives may lead to lower costs and improved health for inmates with cardiovascular risk factors and disease.

Conclusion

Whether incarceration is independently associated with increased cardiovascular risk factors and disease remains unknown. However, what is clear is that prisons and jails house a disproportionate number of individuals who have or are at risk for cardiovascular disease. Acknowledging this reality and making attempts to both study and improve cardiovascular health in prison may mitigate disease among inmates.

Bibliography:

- Baillargeon J, Black SA, Pulvino J, Dunn K (2000) The disease profile of Texas prison inmates. Ann Epidemiol 10:74–80

- Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, Koepsell TD (2007) Release from prison – a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med 356:157–165

- Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF (2009) Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the United States compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health 63:912–919

- Conklin TJ, Lincoln T, Tuthill RW (2000) Self-reported health and prior health behaviors of newly admitted correctional inmates. Am J Public Health 90:1939–1941

- Cropsey K, Eldridge G, Weaver M, Villalobos G, Stitzer M, Best A (2008) Smoking cessation intervention for female prisoners: addressing an urgent public health need. Am J Public Health 98:1894–1901

- Cuomo C, Sarchiapone M, Giannantonio MD, Mancini M, Roy A (2008) Aggression, impulsivity, personality traits, and childhood trauma of prisoners with substance abuse and addiction. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 34:339–345

- Damberg CL, Shaw R, Teleki SS, Hiatt L, Asch SM (2011) A review of quality measures used by state and federal prisons. J Correct Health Care 17:122–137

- Engel GL (1971) Sudden and rapid death during psychological stress. Folklore or folk wisdom? Ann Intern Med 74:771–782

- Eves A, Gesch B (2003) Food provision and the nutritional implications of food choices made by young adult males, in a young offenders’ institution. J Hum Nutr Diet 16:167–179

- Flanagan NA (2004) Transitional health care for offenders being released from United States prisons. Can J Nurs Res 36:38–58

- Ha BC, Robinson G (2011) Chronic care model implementation in the California State Prison System. J Correct Health Care 17:173–182

- Iribarren C, Sidney S, Bild DE, Liu K, Markovitz JH, Roseman JM, Matthews K (2000) Association of hostility with coronary artery calcification in young adults: the CARDIA study. Coronary artery risk development in young adults. JAMA 283:2546–2551

- Leddy MA, Schulkin J, Power ML (2009) Consequences of high incarceration rate and high obesity prevalence on the prison system. J Correct Health Care 15:318–327

- Loeb SJ, Steffensmeier D, Myco PM (2007) In their own words: older male prisoners’ health beliefs and concerns for the future. Geriatr Nurs 28:319–329

- Mallik-Kane K, Visher CA (2008) Health and prisoner reentry: how physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration. The Urban Institute, Washington, DC

- Massoglia M (2008) Incarceration as exposure: the prison, infectious disease, and other stress-related illnesses. J Health Soc Behav 49:56–71

- Matthews KA, Zhu S, Tucker DC, Whooley MA (2006) Blood pressure reactivity to psychological stress and coronary calcification in the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Hypertension 47:391–395

- Mumola CJ (2007) Medical causes of deaths in state prison, 2001–2004. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Washington, DC

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care (2002) The health status of soon-to-be-released inmates: a report to congress I & II. NCCHC, Chicago Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Wohl DA (2008) All-cause and cause-specific mortality among men released from state prison, 1980–2005. Am J Public Health 98:2278–2284

- Sabbah W, Watt RG, Sheiham A, Tsakos G (2008) Effects of allostatic load on the social gradient in ischaemic heart disease and periodontal disease: evidence from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Epidemiol Community Health 62:415–420

- Spaulding AC, Seals RM, McCallum VA, Perez SD, Brzozowski AK, Steenland NK (2011) Prisoner survival inside and outside of the institution: implications for health-care planning. Am J Epidemiol 173:479–487

- The Pew Center on the States (2009) One in 31: the long reach of American corrections. The Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington, DC

- Travis J (2005) But they all come back: facing the challenges of prisoner reentry. Urban Institute, Washington, DC Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer

- J, Bonomi A (2001) Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 20:64–78

- Wamsley R (2006) World prison population list. King’s College, London

- Wang EA, Wildeman C (2011) Studying health disparities by including incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. JAMA 305:1708–1709

- Wang EA, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Kertesz SG, Kiefe CI, Bibbins-Domingo K (2009) Incarceration, incident hypertension, and access to healthcare: findings from the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Arch Intern Med 169:687–693

- Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, Lasser KE, McCormick D, Bor DH, Himmelstein DU (2009) The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health 99:666–672

- Winter SJ (2011) A comparison of acuity and treatment measures of inmate and noninmate hospital patients with a diagnosis of either heart disease or chest pain. J Natl Med Assoc 103:109–115

- Young M, Waters B, Falconer T, O’Rourke P (2005) Opportunities for health promotion in the Queensland women’s prison system. Aust N Z J Public Health 29:324–327

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.