This sample Nursing Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Professional Nursing Practice

In virtually all countries, nurses make up the largest group of health-care professionals. In some countries, they are the first, and sometimes only, point of contact populations have with the health-care system. Considered the most diversified professionals in health care, nurses are widely recognized as an essential resource to the effectiveness of any health system.

Nursing is a large, highly skilled, versatile, and dynamic workforce that is continuously evolving in response to changing societal health and social needs. As with other health professions, nursing is shaped by the social, economic, political, and cultural context within which it is practiced. These contextual influences give rise to wide variations internationally in terms of the role of nurses, their scope of practice, educational preparation, work environments, career structures, position within the health system and society, and legal and regulatory status.

Throughout nursing’s history individuals and organizations have sought to define nursing. Today, the most universally accepted and widely used definition of nursing originates from the work of the International Council of Nurses (ICN). Over a century old, the Council is a federation of national nurses’ associations that today speaks on behalf of more than 13 million nurses worldwide. Operated by nurses for nurses, ICN works to unite nurses worldwide and improve standards of nursing care. The ICN definition of nursing, drawn up in 1987, states:

Nursing, as an integral part of the health-care system, encompasses the promotion of health, prevention of illness, and care of physically ill, mentally ill, and disabled people of all ages, in all health-care and other community settings. Within this broad spectrum of health care, the phenomena of particular concern to nurses are individual, family, and group responses to actual or potential health problems. These human responses range broadly from health restoring reactions to an individual episode of illness to the development of policy in promoting the long-term health of a population.

The unique function of nurses in caring for individuals, sick or well, is to assess their responses to their health status and to assist them in the performance of those activities contributing to health or recovery or to dignified death that they would perform unaided if they had the necessary strength, will, or knowledge and to do this in such a way as to help them gain full or partial independence as rapidly as possible. Within the total health-care environment, nurses share with other health professionals and those in other sectors of public service the functions of planning, implementation, and evaluation to ensure the adequacy of the health system for promoting health, preventing illness, and caring for ill and disabled people. (ICN, 2003b: 6)

In addition to the functions described in the ICN definition, nurses are often the coordinators, supervisors, and managers of care provided by other health-care workers and family members. They act as mentors for nursing students, newly qualified nurses, and staff outside the domain of nursing. They are knowledge workers, creative problem solvers, and innovators. They possess technological know-how and use a full range of medical, information, and communication technologies to the benefit of their patients. Moreover, nurses are advocates, educators, and health information and system navigators for patients and families. Lastly, they are champions of primary health care and patient safety.

The practice of nursing is governed by a code of ethics that serves to inform nurses, other health professionals, and the general public about the ethics and values that are intrinsic to the practice of nursing. While some countries have developed their own codes of ethics, others subscribe to the ICN Code of Ethics for Nurses which has served as the standard for nurses worldwide since it was first adopted in 1953 and more recently revised in 2005. The Code makes it explicit that inherent in nursing is the respect for human rights, including the right to life and choice, to dignity, and to be treated with respect (ICN, 2006).

In most countries, the roles, functions, and responsibilities determined to be within the nurse’s scope of practice are defined by law. Depending on the country,

‘‘the authority to decide the educational requirements for professional qualification and license to practise, the development and/or enforcement of nursing practice standards and the resulting disciplinary procedures may be granted by law to the Ministry of Health, a nursing council, a multidisciplinary regulatory body or combinations of the above’’ (ICN, 2004: 5).

Nurses are employed in a wide variety of settings around the world including hospitals, long-term care facilities, community health centers, rural health clinics, rehabilitation centers, public health departments, schools, home care agencies, workplaces, and industry and corporate environments. In addition to delivering direct patient care as clinicians, nurses work as educators, researchers, administrators, and consultants. They may work independently, together with other nurses, or in multidisciplinary teams as generalist, specialist, or advanced practice nurses.

Increasing numbers of nurses are self-employed entrepreneurs. In just about all countries,

‘‘self-employed nurses are legally permitted to offer any service that falls within the practice of nursing and does not infringe on the legislated responsibility or the exclusive practice of another health discipline’’ (ICN, 2003a: 8).

Their functions, services, and work settings differ according to public needs.

Generalist Nursing Practice

Prior to entry into professional nursing practice, a person must first complete an approved basic nursing program and be licensed/registered to practice in their country. The routes to obtaining basic nursing education vary among countries. The most common entry-level paths are diploma and baccalaureate degree programs. However, increasingly countries are moving toward university level education (e.g., baccalaureate degree) as the single route of entry to practice.

In most countries, on entry to practice a nurse is called a Registered Nurse; in others a Licensed Nurse, First Level or a Qualified Nurse. Irrespective of these different professional designations, the generalist nurse is equipped and authorized to

‘‘(1) engage in the general scope of nursing practice, including the promotion of health, prevention of illness, and care of physically ill, mentally ill, and disabled people of all ages in all health-care and other community settings; (2) carry out health-care teaching; (3) participate fully as a member of the health-care team; (4) supervise and train nursing and health-care auxiliaries; and (5) be involved in research’’ (ICN, 2003b: 6).

Further, the generalist nurse has the competence to provide primary, secondary, and tertiary level care across all settings and fields of nursing (ICN, 2003b).

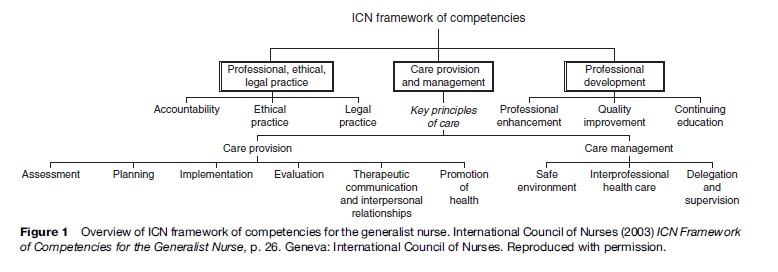

It is this generalist preparation that serves as the foundation for specialist and advanced practice roles in nursing. In 2000, in response to worldwide demand for direction on professional nursing competencies, ICN established international competencies for the generalist nurse. The ICN Framework of Competencies for the Generalist Nurse is broad enough to be applied internationally, but specific enough to provide guidance to countries developing their own competencies. An overview of the framework is shown in Figure 1. ICN is currently working to develop international competencies for the specialist and advanced practice nurse.

Specialty Nursing Practice

Specialization in nursing is not a modern phenomenon. Early in the profession’s development it was recognized that certain patient groups and practice settings required practitioners with more focused and specialized knowledge and skills than could be successfully acquired through basic nursing education. Over the last two decades, the pace of specialization in nursing has accelerated steadily, spurred on by a rise in medical specialization and a parallel growth in medical and nursing knowledge and technology. Changing patient needs and transformations in the way health care is organized have also prompted greater levels of specialization in nursing (ICN, 1992).

Today nurse specialists can be found practicing in clinical, teaching, administration, research, and consultant roles in a wide variety of specialty areas and health-care settings. Typically, such roles are defined in terms of the patient group or population (e.g., pediatrics), the disease/ pathology (e.g., diabetes), or by the practice setting (e.g., critical care). Nurses may also subspecialize within a specialty area of practice. For instance, a pediatric nurse may have subspecialty education in pediatric oncology nursing.

The pathways to specialization differ from country to country. However, in most cases, specialization is acquired through experiential preparation and formal postbasic or postgraduate education. With the rise in specialization, a number of countries have established programs for voluntary certification that grant recognition of competence in a nursing specialty. Examples of areas where voluntary certification are available include: critical care, oncology, emergency, diabetes, infection control, informatics, nephrology, forensics, palliative care, pain management, mental health, orthopedics, pediatrics, and urology.

Advanced Nursing Practice

The rapid and complex changes taking place in health systems worldwide continue to present opportunities for nurses to expand and advance their practice roles to better meet and respond to the needs of the people and systems they serve. Several forces have converged to influence the growing number of and demand for advanced practice roles in nursing. These include gaps in health service coverage, particularly in rural and remote communities; rising demand for specialized nursing roles; workforce shortages; escalating global burden of disease; and economic pressures and rising consumer expectations (Schober, 2002, in Affara and Schober, 2006; Furlong and Smith, 2005).

Advanced nursing practice (ANP) is one of a number of diverse professional paths available to nurses. It has been estimated that close to 40 countries have established or are in the process of developing advanced practice nursing roles. Examples include Canada, the United States, Hong Kong, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Botswana, Taiwan, Switzerland, Japan, and Spain.

ANP is an umbrella term that refers to ‘‘an advanced level of nursing practice that maximizes the use of indepth nursing knowledge and skill in meeting the health needs of clients (individuals, families, groups, populations or entire communities)’’ (Canadian Nurses Association, 2006: 1). The term encompasses four commonly identified role titles: nurse practitioner, certified nurse midwife, certified nurse anesthetist, and clinical nurse specialist. However, it is important to note that titling, as well as educational preparation, regulatory requirements, role definition, and scope of practice vary depending on the country (Affara and Schober, 2006).

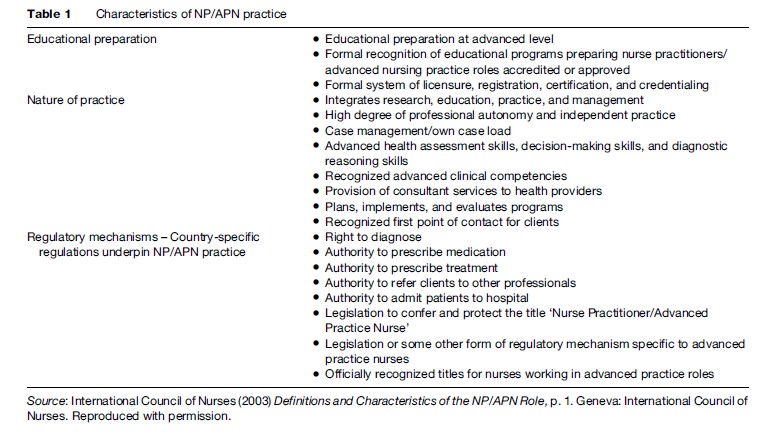

To facilitate a common understanding and to guide the future development of advanced practice roles, ICN, working with its International Nurse Practitioner/ Advanced Practice Nursing Network, has developed a definition and characteristics of practice for the Nurse Practitioner/Advanced Practice Nurse (NP/APN) (see Table 1). ICN defines the NP/APN as

‘‘a registered nurse who has acquired the expert knowledge base, complex decision-making skills and clinical competencies for expanded practice, the characteristics of which are shaped by the context and/or country in which s/he is credentialed to practice. A master’s degree is recommended for entry level’’ (ICN, 2003c: 1).

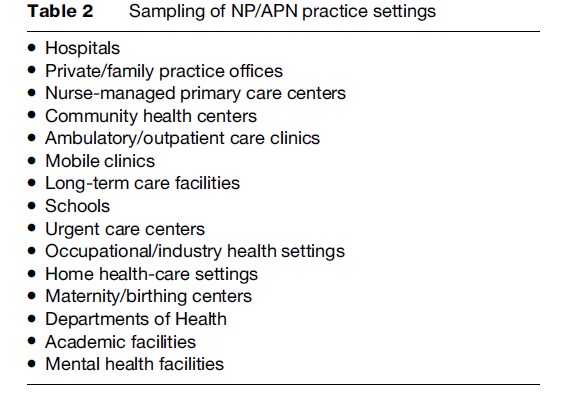

NP/APNs provide care across the health continuum spanning from health promotion and illness prevention to curative, rehabilitative, and supportive services. They provide care to individuals, families, groups, and communities across the life span. NP/APNs practice in a variety of sectors (e.g., public and private) and geographic locations (e.g., urban and rural) as well as settings. Table 2 provides a sampling of NP/APN practice settings. They may practice autonomously or in collaboration with a variety of health and social care providers such as physicians, other nurses, social workers, and therapists. While advanced practice nursing is at various stages of development and implementation around the world, the literature suggest that this trend will continue well into the future, particularly as more countries embrace this role.

Nurses’ Contribution To Health Services

Whether practicing in generalist, specialist, or advanced practice roles, nurses are making a considerable and positive impact on the provision of health services. There is a well-established and expanding body of research evidence documenting the effectiveness of their care. For instance, outcome research indicates that care provided by NP/ APNs is equivalent to that of physicians (Brown and Grimes, 1995; Mundinger et al., 2000). Further, care delivered by NP/APNs has been associated with improved patient satisfaction, reduced hospital lengths of stay, improved quality of life, lower hospital re-admission rates, better health education, and decreased health-care costs (Brown and Grimes, 1995; Kinnersley et al., 2000; Mundinger et al., 2000; Ritz et al., 2000; Venning et al., 2000; Naylor et al., 2004). There are also a significant number of research studies linking higher numbers and a richer mix of qualified/registered nurses to reductions in patient mortality, rates of respiratory, wound, and urinary tract infections, number of patient falls, incidence of pressure sores, and medication errors (see West et al., 2004).

When natural or manmade disasters strike, nurses are often the first wave of responders and major contributors to the restoration of public health services post-disaster. They make a significant contribution to national and international efforts targeting the health and social problems of refugees, displaced persons, and migrants resulting from disasters, political turmoil, and civil strife.

Nurses make a valuable and unique contribution to health services through research. They employ both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies to evaluate, validate, and refine existing knowledge and to generate new knowledge in relation to nursing and health services. The knowledge generated through nursing research is used to inform nursing education, practice, and management, to shape health policy, and to enhance the health and well-being of populations.

Not surprisingly, nurses are also found at the forefront of innovative discoveries in health care. They use their creative capacity to find solutions to both old and new problems many of which have led to improvements in the health of patients, the day-to-day work life of nurses, and the way in which health services are delivered. Increasingly nurses are being called on by the pharmaceutical industry, manufacturers of medical devices, and health information technology suppliers to participate in, or lead, new product research and development. Internationally, novel solutions by nurses abound, some of which are being captured in the International Council of Nurses Innovations Database.

Professional Nursing Organizations

Professional organizations have long been an integral part of the nursing profession providing a medium through which nurses with common goals and interests work collectively for the benefit of society and the advancement of the profession (ICN, 1996a).

Nurses join professional organizations for various reasons. For example, some see membership as the first step toward becoming identified with the profession, while others view membership as a way to stay current on professional issues and developments, to access networking opportunities, to exchange ideas, information, and experiences with colleagues and/or as a means to achieve continuing professional growth and education (ICN, 1996a). A nurse may choose to hold membership in one or more professional organizations or associations.

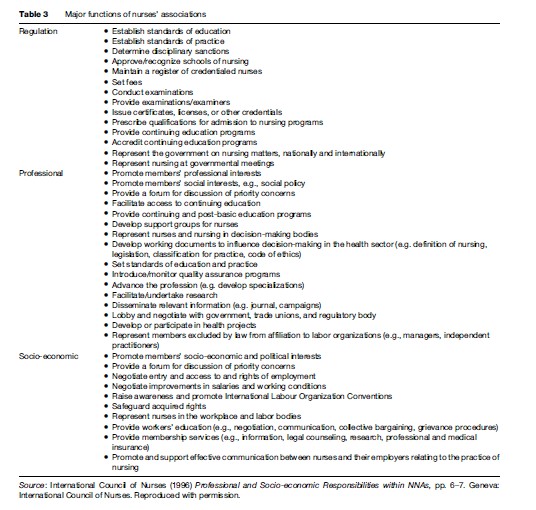

In all countries, the nursing profession is organized in the form of national nurses’ associations. In some countries, these associations are federations of affiliated provincial or state nursing organizations while in others they are nonfederated entities. The functions of such associations are diverse, but can be broadly categorized as regulatory, professional, and socioeconomic. An association may perform one or more of these functions. The most common models seen today are: (1) professional association and regulatory body; (2) professional association and regulation responsibilities for continuing and post-basic education and qualifications; (3) professional association with programs also focused on members’ individual interests and concerns; and (4) professional association and socioeconomic welfare organization/negotiating body (ICN, 1996b).

The purpose and functions of an association may be influenced by a number of local external factors. These include the health-care system in which the association is located, legislation and societal changes, the type of association, the role and social status of nurses, the role of other nursing associations, and globalization and regionalization (ICN, 1996a). Some examples of major functions that may be carried out by nurses’ associations are highlighted in Table 3.

There are also a number of well-established specialty nursing organizations that have evolved over the past several decades as the profession has become more specialized. Such organizations are most often formed around a defined area of specialty nursing practice, such as oncology, gerontology, or public health. They may be autonomous organizations, or they may form a branch of a larger national nursing association. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, established in 1969, is one the world’s largest specialty nursing organizations.

Additionally, there are organizations that speak for nursing at the regional and global levels. For example, the Caribbean Nurses Organization, founded in 1957, is the regional voice for nursing in the Caribbean. At the global level, the International Council of Nurses is the largest and oldest organization for nurses.

Nursing organizations may also unite to form interdisciplinary alliances with other organizations. One such example is the World Health Professions Alliance which brings together dentistry, medicine, nursing, and pharmacy through their representative international organizations, the International Council of Nurses, the International Pharmaceutical Federation, the World Dental Federation, and the World Medical Association. Together, they represent the interests of more than 20 million health professionals worldwide.

Historically, professional organizations have played an important role in nursing’s development. Today, nursing organizations and associations, whether operating at the local, national, regional, or international level, remain committed to promoting improvements in the standards of nursing care and to advancing the profession, health services, and the health and well-being of society as a whole.

Global Nursing Workforce Shortage

One of the most pressing challenges facing health-care systems and the nursing community worldwide is the growing shortage of nurses. Globally, there is wide acknowledgment that the scarcity of nurses, combined with the short supply of other health workers, is rapidly establishing itself as a major threat to public health in many nations. In a number of countries, the shortage of health workers, particularly nurses, is placing a tremendous burden on already overtaxed health systems and is creating a major barrier to the provision of essential health services. For others, notably the least developed countries, inadequate human resources have become the most significant constraint on the attainment of national and international health and development goals.

Current and predicated nursing shortages, in both developed and developing countries, have been reported by a number of organizations including the World Health Organization, the World Bank, the Pan American Health Organization, the International Council of Nurses, Physicians for Human Rights, and the Global Health Trust. Nowhere in the world is the shortage said to be more pronounced or severe than in sub-Saharan Africa where deficiencies in supply are exacerbated by the international movement of nurses to more developed countries in search of better working conditions and quality of life. In countries of this subregion, it is not uncommon to find one nurse responsible for providing care to 50 to 100 patients at one time.

Nursing shortages are not a new phenomenon. A number of developed countries, notably the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States, have cycled through shortages in the past frequently as a result of demand for nursing services exceeding supply. However, the current shortage is unlike those of the past, as health systems worldwide are experiencing pressures exerted on both the supply of and demand for nurses. While the demand for health services and nurses is growing due to demographic and epidemiological changes, among other factors, the supply of available nurses in many countries is diminishing and is predicted to worsen in the absence of countermeasures.

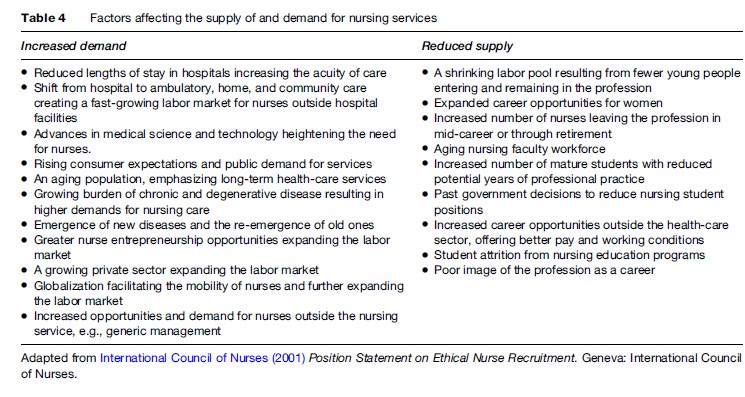

Inadequate human resources planning and management, including poor deployment practices, coupled with high attrition from the workforce (due to poor work environments, low professional satisfaction, and inadequate remuneration), international and internal migration, the impact of HIV/AIDS, and chronic underinvestments in health human resources are major factors driving the current nursing shortage. Additional factors affecting the supply of, and demand for nursing services are highlighted in Table 4.

Ironically, today’s nursing shortages exist parallel with the unemployment of thousands of nurses, particularly in parts of Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe, and Africa. High rates of unemployment are primarily the result of employment/hiring freezes caused by loan conditions placed on borrowing countries by donors and international monetary institutions. As well, a number of countries report underemployment of nurses due to policies and practices that deter them from obtaining fulltime employment.

In a number of countries, nursing shortages coexist with the shortage of nurse educators. These shortages are the result of an aging nursing faculty workforce and a limited pool of younger faculty to replace those retiring. The reduction in the availability of faculty is serving to intensify the current nursing shortage by reducing the ability of education providers to increase their intake of applicants to meet future demand.

The international recruitment and migration of nurses has, in the past decade, become a growing concern for national governments, nursing organizations, employers, and the global health and development community. The World Health Assembly, the World Health Organization’s highest decision-making body, has repeatedly drawn attention to the international migration of skilled health workers and the challenges it poses for health systems, particularly in resource-poor countries.

While not a new phenomenon, the international movement of nurses from developing to developed countries is accelerating. Increasingly, nurses are choosing to leave their native country seeking better working conditions and quality of life elsewhere. Their movement across national borders is attributed to a number of push and pull forces. On the push side are factors such as difficult working environments (often characterized by heavy workloads, risk of exposure to violence, abuse and occupational hazards, lack of autonomy and decision-making authority, limited access to supplies, medication, and technology), low pay, poor career advancement opportunities, lack of non-monetary incentives, and sociopolitical unrest. On the pull side, nurses may migrate to other countries in search of better opportunities for professional development, safer and better equipped working environments, improved remuneration and incentives, greater sociopolitical stability, and a desire for greater professional autonomy.

However, large-scale, and often aggressive international recruitment by developed countries is cited as a major contributing factor to the current high levels of nurse migration. Developed countries have increasingly come to rely on recruiting foreign-trained nurses to fill their domestic shortfalls instead of addressing in-country recruitment and retention issues. The effects of this practice on developing countries include a loss of skilled human capital and economic investments and an inability to adequately meet national health service needs.

Unethical recruitment practices are occurring worldwide and there is a lack of regulatory oversight at both national and international levels. The International Council of Nurses, the World Health Organization, and the Commonwealth Secretariat, while supporting the right of nurses to migrate, have all independently made calls in the form of position statements, resolutions, and codes of practice for better monitoring and more ethical approaches to nurse migration.

In 2005, the International Council of Nurses and the Commission on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools teamed up to establish the International Centre on Nurse Migration – a global resource for the development, promotion, and dissemination of research, policy, and information on nurse migration. The Centre works to address gaps in policy, research, and information with regard to the migrant nurse workforce, including screening and workforce integration.

Internationally, the scarcity of nurses is having a negative impact on patients, health systems, and nursing personnel and there is a significant body of research documenting its impact. For instance, nursing shortages have been linked to increased mortality, accidents, injuries, cross-infection, and adverse postoperative events.

The International Council of Nurses has recently completed a major two-year research and global consultation initiative to document the state of today’s nursing workforce and to inform future policy making. Through its work, the Council has identified five priority areas that require policy attention in the immediate, short, and long term, at both national and international levels. These areas are: macroeconomic and health sector funding policies; workforce policy and planning, including regulation; positive practice environments and organizational performance; recruitment and retention; addressing incountry maldistribution, and out-migration; and nursing leadership. Full details of this work can be obtained on the ICN website.

In 2006, ICN established the International Centre for Human Resources in Nursing. The Centre, whose ultimate aim is to bring about improvements in the quality of patient care through the provision of better managed health care and nursing services, serves as an online gateway to comprehensive information, resources, and analysis on nursing human resources policy, management, and practice.

The World Health Assembly has repeatedly recognized the essential role nurses and midwives play in the provision of effective health services and has made calls, through numerous resolutions, to strengthen the workforce. In 2006, during the 59th session of the Assembly, 192 member states unanimously adopted a major resolution to strengthen nursing and midwifery. The resolution urges member states to commit to strengthening the workforce by:

(1) establishing comprehensive programmes for the development of human resources which support the recruitment and retention, while ensuring equitable geographical distribution, in sufficient numbers of a balanced skill mix, and a skilled and motivated nursing and midwifery workforce within their health services; (2) actively involving nurses and midwives in the development of their health systems and in the framing, planning and implementation of health policy at all levels, including ensuring that nursing and midwifery is represented at all appropriate governmental levels, and have real influence; (3) ensuring continued progress toward implementation at country level of WHO’s strategic directions for nursing and midwifery; (4) regularly reviewing legislation and regulatory processes relating to nursing and midwifery in order to ensure that they enable nurses and midwives to make their optimum contribution in the light of changing conditions and requirements; (5) to provide support for the collection and use of nursing and midwifery core data as part of national health information systems; (6) to support the development and implementation of ethical recruitment of national and international nursing and midwifery staff. (WHO, 2006: 1–2)

Conclusion

Nurses are the single largest group of health-care professionals in most countries. As such they are a vital input in all health systems. Internationally, nurses are evolving their roles and reconfiguring their practice to meet the complex challenges facing health systems and the changing health and social needs of individuals, families, groups, populations, and communities. Ensuring their adequacy in numbers, skills, and distribution is paramount to quality, equity, safety, and cost-effectiveness in patient care and health services around the world.

Bibliography:

- Brown SA and Grimes DE (1995) A meta-analysis of nurse practitioners and nurse midwives in primary care. Nursing Research 44(6): 332–339.

- Canadian Nurses Association (2006) Report of 2005 Dialogue on Advanced Nursing Practice. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Nurses Association.

- Furlong E and Smith R (2005) Advanced nursing practice: Policy, education and role development. Journal of Clinical Nursing 14: 1059–1066.

- International Council of Nurses (1992) Guidelines on Specialisation in Nursing. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- International Council of Nurses (1996a) Resource Manual for Associations in Membership with the International Council of Nurses. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- International Council of Nurses (1996b) Professional and Socio-economic Responsibilities within NNAs. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- International Council of Nurses (2001) Position Statement on Ethical Nurse Recruitment. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- International Council of Nurses (2003a) Guidelines on the Nurse Entre/ Intrapreneur Providing Nursing Service. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- International Council of Nurses (2003b) ICN Framework of Competencies for the Generalist Nurse. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- International Council of Nurses (2003c) Definitions and Characteristics of the NP/APN Role. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- International Council of Nurses (2004) Guidelines: Law and the Workplace. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- International Council of Nurses (2006) The ICN Code of Ethics for Nurses. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- Kinnersley P, Anderson E, Parry K, et al. (2000) Randomised controlled trial of nurse practitioner versus general practitioner care for patients requesting ‘‘same day’’ consultations in primary care. British Medical Journal 320: 1043–1048.

- Mundinger M, Kane R, Lenz E, et al. (2000) Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 283: 59–68.

- Naylor M, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. (2004) Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52(5): 675–684.

- Ritz L, Nissen M, Swenson K, et al. (2000) Effects of advanced nursing care on quality of life and cost outcomes of women diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncolodgy Nursing Forum 27: 923–932.

- Schober M and Affara F (2006) International Council of Nurses: Advanced Nursing Practice. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Venning P, Durie A, Roland M, Roberst C, and Leese B (2000) Randomised control trial comparing cost effectiveness of general practitioners and nurse practitioners in primary care. British Medical Journal 320: 1048–1053.

- West E, Rafferty AM, and Lankshear A (2004) The Future Nurse: Evidence of the Impact of Registered Nurses. London: Royal College of Nursing.

- WHO (2006) Strengthening Nursing and Midwifery. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Baumann A, Blythe J, Kolotylo C, and Underwood J (2004) The International Nursing Labour Market. Ottawa, Canada: The Nursing Sector Study Corporation.

- Buchan J and Calman L (2004) The Global Shortage of Registered Nurses: An Overview of Issues and Actions. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- Henderson V (2004) ICN’s Basic Principles of Nursing Care, 4th edn. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- International Council of Nurses (1996) Nursing Education: Past and Present. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- International Council of Nurses (2006) The Global Nursing Shortage: Priority Areas for Intervention. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- Kingma M (2006) Nurses on the Move: Migration and the Global Health Care Economy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Madden-Styles M and Affara F (1998) ICN on Regulation: Towards 21st Century Models. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses.

- WHO (1997) Nursing Practice Around the World. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- WHO (2002) Strategic Directions for Nursing and Midwifery Services. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- WHO (2006) Working Together for Health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.