This sample Psychotic Disorders Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Terminology

Psychiatry has always paid great attention to the use of certain terms to denote or describe a particular mental illness or behavior in an attempt to destigmatize and demystify the suffering of people affected by a mental illness. Terms such as madness and insanity, which denoted a mental disorder with severe disturbance of behavior, have fortunately become unusable now. The term psychosis became the officially acceptable term to denote these disorders, qualified by schizophrenic or manic, for example, to identify the individual diagnostic entity. They are also known as severe mental disorders (SMDs) and low-prevalence disorders (LPDs). More recently, the term psychosis has been replaced by the term disorder preceded by the qualifying term (e.g., schizophrenic disorder). The term psychosis has now come to denote a cluster of symptoms rather than a distinct diagnostic entity. The adjective schizophrenic or manic is now used to describe the disorder and not the person suffering from the disorder. We use the term psychotic disorders here to denote a group of mental disorders characterized by a particular set of symptoms, severity of disablement, treatment needs, and public health importance.

History

Psychotic disorders are not new maladies of the emerging modern world. They have been described in ancient texts of various civilizations across the world, some dating back as far as the third millennium BC. It is surprising, in a way, to note the similarities in descriptions of the disorders in the ancient and modern texts. The description ‘‘.. . one who is gluttonous, filthy, walks naked, .. . lost his memory and moves about in an uneasy manner.. .’’ in the Ayur Veda written in 3500 BC compares with the symptoms described in modern classification systems of psychiatric disorders. A more precise clinical description of psychotic disorders was given by Haslam in 1809 followed by Morel in 1860. It was toward the end of the nineteenth century and early years of the twentieth century that description of what is currently called schizophrenia and its differentiation from what we now know as bipolar disorder were described. Emil Kraepelin of Germany in 1896 and later Eugen Bleuler of Switzerland were accredited with this ground-breaking clinical work. Delineation and description of psychotic disorders underwent many changes during the twentieth century, with major work emerging from the Anglo-American and European schools of thought. It is interesting to note that the clinical classification system currently adopted worldwide, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), are not far-removed from the seminal works of Krepelin and Bleuer.

Psychotic Disorders

Psychotic disorders are those disorders of mental function and behavior that are severe in nature and cause severe disruption to the individual’s functioning capacity and requires active and often long-term medical and psychosocial treatment. They are differentiated from the nonpsychotic or minor mental disorders by the nature of symptoms, morbidity, etiology, treatment, course, and outcome. It is important to note that the so-called minor mental disorders can sometimes cause suffering and disruption to life activities to a level comparable to that caused by psychotic disorders.

Schizophrenia, mood disorders, and paranoid disorder are the commonest forms of psychotic disorders. A fourth group of disorders that have some of the features of the other three but are different in some aspects (etiology, duration, course and outcome, cultural influences) are together classified as ‘Other psychotic disorders’. This discussion does not include psychotic disorders caused by known medical conditions such as brain damage or psychotropic substances and some culture-specific syndromes. It focuses on schizophrenia and mood disorders that are the most common and disabling of psychotic disorders.

Symptoms Of Psychotic Disorders

The symptoms of a psychotic disorder are manifest in the patient’s emotions, perception, thinking, speech, and behavior. Disturbed emotion manifests in the form of excess sadness or happiness. In mood disorders, the patient’s thinking and behavior match the mood they are experiencing (e.g., the patient feels worthless, becomes dull and inactive when depressed, is overactive, and indulges in excess spending and social misadventures when manic). Disordered perception takes the form of hallucinations where the person has sensations in the absence of any relevant stimulus and may respond to them as if they were true (e.g., hears voices of people talking to him or her when alone). Thinking disturbance in the form of delusions, which are fixed beliefs, are held even in the presence of definite evidence to the contrary (e.g., a belief that aliens are attacking him or her or that he or she is God). Patients may become mute or their speech rambling and difficult to follow. Their behavior often contravenes the normal behavior expected of the person and can be bizarre or harmful (violent, dirty, and disheveled appearance, silly behavior). Occasionally patients exhibit catatonia, where they may assume peculiar posturing with limbs held rigid for long periods of time. Disturbances in sleep, appetite, and sexual activity are common symptoms. There can be a severe reduction in the patient’s interpersonal interactions, emotional life, motivation, and interest in life activities, a drop in academic and work capacity and the ability to take care of oneself. These symptoms are known as negative symptoms. Patients also experience disturbed attention, concentration, memory, and ability to plan and execute day-to-day tasks. Death by suicide occurs in 10–15% of those with psychotic disorders. Patients with psychosis are at a higher risk to commit violent or homicidal crime (Eronen et al., 1996).

Diagnosis

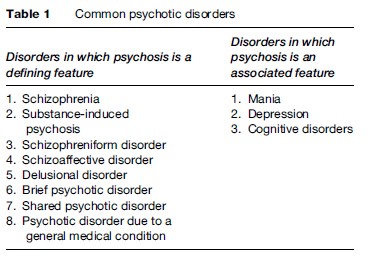

Diagnosis of a psychotic disorder is made mainly through clinical interview with the affected person and observation by a mental health professional with the affected person. Collateral and corroborative information about the person and his or her behavior is sought from relatives, friends, and medical records. Laboratory investigations such as screening for the use of drugs such as amfetamines, blood tests, and neurological investigations such as a CT scan are ordered to identify any medical disorder causing the symptoms of a psychotic disorder (Tables 1 and 2).

Diagnosis of schizophrenia is made when a combination of symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, behavior changes, and negative symptoms predominate. The predominant symptom of a mood disorder is an excess of emotion of depression (depressive disorder) or happiness (manic disorder). Bipolar disorder refers to the condition where both depression and mania occur in the same person at the same time or different points in time. Patients are diagnosed with paranoid disorder when they have only a delusion (e.g., of being persecuted or having a serious disease) but rarely other symptoms.

Epidemiology

The majority of epidemiological studies have produced prevalence estimates in the range of 1.4–4.6/1000 for schizophrenia and 4–5/1000 for bipolar disorder, while it is much higher at 2–5% for major depression. The life-time morbid risk for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder is estimated at 1% and 10–20% for major depression. The annual incidence ranges from 0.017 to 0.054% for schizophrenia and from 0.003 to 0.01% for bipolar disorder. These estimates are unlikely to reflect the true extent of variation that exists in different populations.

Causes

Extensive research has been conducted to identify the causes of the two major psychoses: schizophrenia and mood disorders. Several factors have been put forward to explain their cause. The disorders are probably multifactorial in origin, involving genetic, biological, and environmental factors.

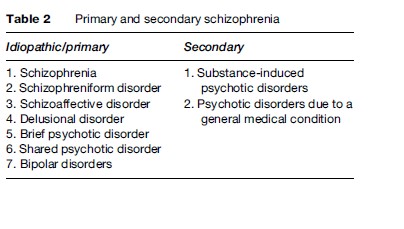

Genes seem to play a rather important role in the causation of schizophrenia. The risk of developing the disorder increases tenfold if a parent or sibling is affected and 40to 50-fold when an identical twin has the illness (Figure 1). Current molecular genetic research has identified several gene loci related to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder but has not yet established a strong and consistent link to the illness. Psychologically stressful experiences throughout life and use of psychotropic substances are also related to the development of psychotic disorders. It is currently being hypothesized that people who develop schizophrenia have a disorder in the development of their brains from the period before birth and/or during the early years of life. These defects could be caused by genetic or environmental factors. Vulnerability is a concept that has helped explain why some individuals and not others develop psychotic disorders, given the same background and environment. This vulnerability could be in the form of a family history of illness or a neurodevelopmental defect. Life stresses or use of psychotropic substances can precipitate an episode of psychosis in a vulnerable individual. It should be noted, however, that a majority of individuals apparently develop psychotic disorders without any identifiable preexisting or precipitating cause.

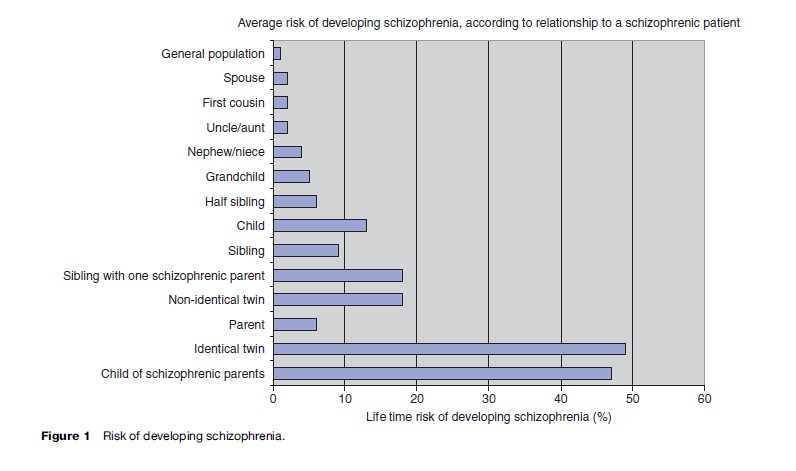

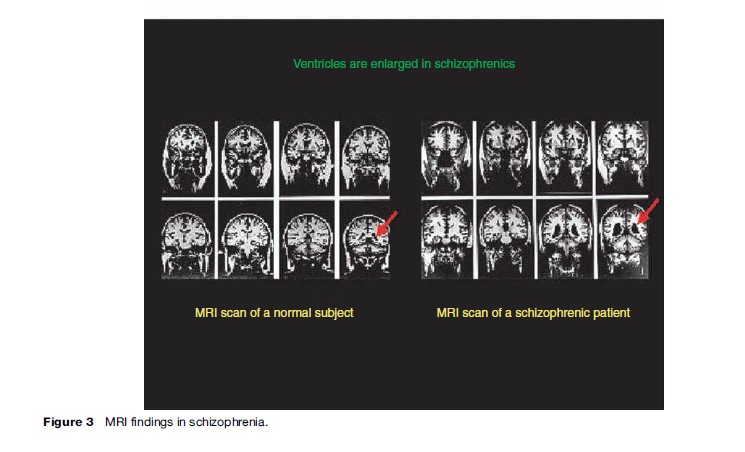

Abnormalities in the activity of certain areas of the brain such as the temporal and frontal lobes of the cerebrum and changes in neurochemistry have been identified in people with psychosis (Figure 2 and 3). For example, increased activity of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that is involved in conducting signals between nerve cells, is implicated as the fundamental defect in schizophrenia. Nothing has yet been concluded about how brain defects are related to the manifestation of and recovery from psychotic disorders.

Treatment And Outcome

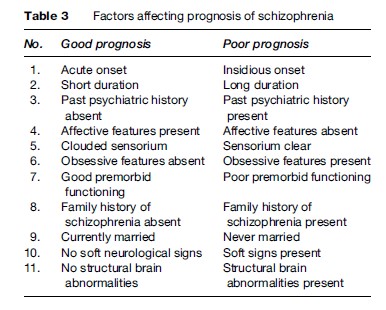

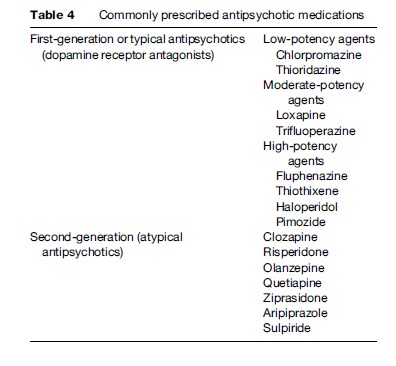

A combination of medications and psychological and social interventions provide the best chances of recovery for people with psychotic disorders (Table 3). Antipsychotic medications such as clozapine and mood stabilizers such as lithium are used (Table 4). Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is indicated for a small percentage of severely ill patients, especially those with depression. Psychological interventions include cognitive behavior therapy, social skills training, mental health education, drug abstinence programs, stress management, training in independent living skills, and educational and vocational rehabilitation. Social intervention focuses on reducing stigma and supporting patients’ reintegration into the mainstream community. It includes public health education programs, empowerment of patients and their caregivers, protection of rights and citizenship, ensuring equal opportunities, encouraging economic independence, social participation, and legal protection. Active and collaborative engagement of the patient, the family, and other caregivers in the treatment process is the recommended practice. Given the social relevance and magnitude of mental illness, an active and informed involvement of the legislature, judiciary, and mass media is essential for better outcomes, quality of life, and social reintegration of patients suffering from psychotic disorders.

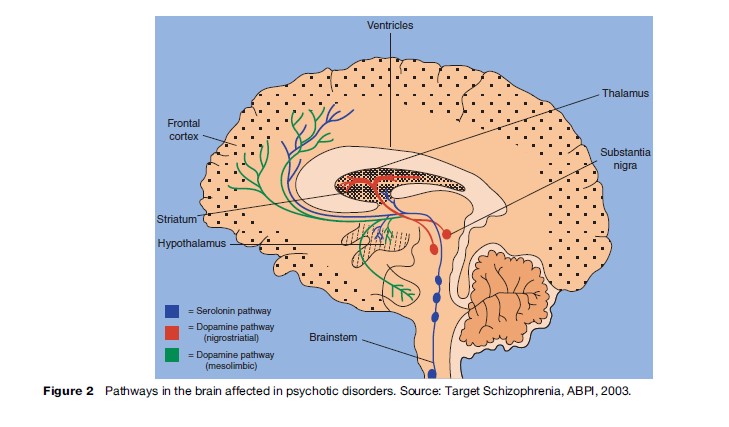

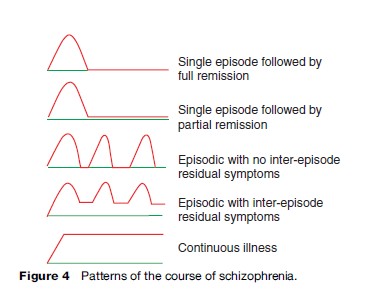

The course of psychotic disorders varies between individuals. Generally, approximately one-third of patients recover fully after the first episode of illness. A majority experience a course marked by relapses (reemergence of frank symptoms of the disorder) interspersed with periods of varying degrees of recovery or a continuous illness (Figure 4).

Public Health And Psychotic Disorders

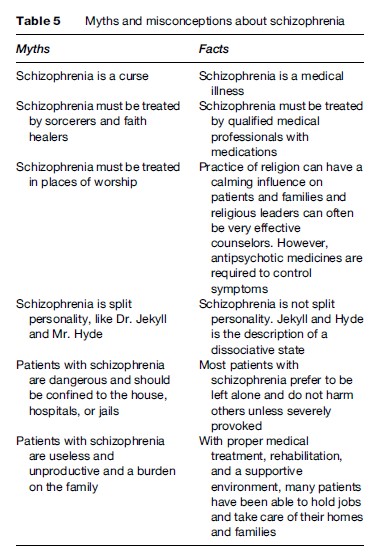

There is a common perception that psychotic disorders are not of as much public health importance as more prevalent and physically obvious disorders such as infectious diseases, heart disease, and cancer. During the last century, clinical knowledge and the practice of psychiatry and allied disciplines have advanced enormously. Worldwide research has shown that some of the psychotic disorders are no longer so-called low-prevalence disorders. We now know that the disabilities suffered by persons with psychotic disorders are equivalent to those caused by serious medical disorders. The very nature of psychotic disorders, with yet unclear etiology, chronicity with onset often in young age, and lack of a definitive cure tend to create a cumulative public health burden. The widespread lack of public knowledge and misinformation (Table 5), the stigma and marginalization faced by people suffering from these disorders, inadequate and inappropriate mental health, and long-term care services place more constraints in the effective management of these disorders. This leads to a substantial unattended public health burden that is often borne by the sufferer and the community.

Morbidity And Mortality

Mortality rates are used as global measures of a population’s health status and as indicators for public health efforts and medical treatments. Psychotic disorders often have a fatal outcome. The average life expectancy of patients with schizophrenia is 20% less than that of the community they live in. Approximately 10–20% of people with psychotic disorder die by suicide, while 20–55% make medically serious attempts at suicide. These rates are at least 20 times more than those recorded for the general population.

People with a psychotic disorder suffer from many medical disorders at rates higher than other people. Comorbid medical illnesses have been detected in up to 40% of patients with schizophrenia in the community. The rate is higher among those in a hospital setting. Obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, abnormalities in lipid metabolism, coronary heart disease, hypertension, emphysema, tuberculosis, and cancer occur at higher rates in people with psychotic disorders than the general population. While some of the metabolic abnormalities are associated with treatment with antipsychotic drugs, individuals with schizophrenia are, by nature, said to have a greater tendency to develop these disorders even in the absence of any drug treatment. These medical disorders add to the burden of disease borne by these patients and further reduce their ability to function normally and their quality of life.

Disability And Burden Caused By Psychotic Disorders

The term ‘disabled’ commonly brings up the picture of a person with impairment in physical function such as vision or mobility. Many fail to recognize that people with mental disorders can suffer disabilities qualitatively and quantitatively similar to those caused by a physical illness. According to the United Nations Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, the term disability ‘‘summarizes a great number of different functional limitations occurring in any population in any country of the world. People may be disabled by physical, intellectual or sensory impairment, medical conditions or mental illness.’’ The International Classification of Functioning (ICF) developed by the World Health Organization describes and classifies various forms of disability independent of the cause. Psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia have been recognized the world over as conditions that cause major disabilities in several spheres of a person’s functioning: self-care, independent living, social activity and social role function, educational and occupational skills, and cognitive capacity.

Psychotic disorders contribute to the overall disease burden, which is generally underestimated. In a major study conducted by the World Bank and the World Health Organization, it was reported that no less than 25% of the total burden of disease in the established market economies was attributable to neuropsychiatric conditions. Measured as a proportion of disability-adjusted life years (DALY) lost, which is an estimate of healthy years of life lost due to an illness, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression together accounted for 10.8% of the total burden of disease in the world. This means that these three disorders together inflict on most communities losses that are comparable to those caused by cancer (15%) and higher than the losses resulting from ischemic heart disease (9%). The study projected depression to rank as the number one cause of disability by the year 2020.

Cost Of Psychosis

Psychotic disorders impose considerable cost to the patient, family, and society. Direct costs include cost of mental health services, medicines, and support costs. Indirect costs include loss of productivity of the patients and their carers and the cost of pain and suffering of patient and family. The average costs of psychoses are high even when estimated conservatively. The total cost of schizophrenia alone in the United States in 1990 was estimated at $32.5 billion, followed by affective (mood) disorders at $30.4 billion. Despite the worldwide policy of closing costly-to-run psychiatric hospitals, the cost of psychosis appears to be rising each year. This is worsened by the increasing cost of the new generation of antipsychotic medications that are recommended in place of low-cost medications, with no clearly demonstrated advantages in terms of effectiveness or safety. The cost of psychosis is also borne by the community with varying degrees of willingness and consequence. Absence of welfare support programs and poor public health care in developing countries place the entire cost of patient care on families, resulting in their poverty, marginalization, and downward social drift.

Smit et al. (2006) drew attention to some of these issues related to the burden of disease attributable to psychotic disorders and drew up priorities in managing this burden. At the population level, new patients caused a substantial part of the costs. This was a strong argument for strengthening the role of preventive psychiatry in public health, with the aim of reducing incidence, thus avoiding future costs. In particular, reducing the incidence of highly prevalent disorders such as major depression, associated with substantial disability and important economic ramifications, should be a public health priority. Smit et al. noted further that the bulk of the costs resulted from production losses; this made employers pertinent stakeholders in mental health promotion. Therefore, thought should be given to the question of how to involve them more actively in health promotion. Adoption of the abovementioned strategies would need to be supported by more prevention trials and cost-effectiveness studies on the specific disorders. With the costs of mental disorders comparable to those resulting from physical illnesses, there is a need to reconsider how budgets are allocated for research and development in mental illnesses vis-a-vis physical illnesses.

Stigma Of Psychosis

Stigma is a social phenomenon that places people in a particular social or health status at a disadvantage. WHO defined stigma as a mark of shame, disgrace, or disapproval, which results in an individual being shunned or rejected by others. A diagnostic label such as schizophrenia or mania is often feared and rejected by those who receive it. The need to use psychotropic prescription medications that are often viewed as addicting play a role in creating the stigma. Behavioral deviations in personal hygiene, social skills and communication, homelessness, and unemployment contribute to the stigma faced by people with psychotic disorders. The imbalance in the focus of mass media on disabilities resulting from mental disorders often reinforces stigma.

Stigma has the potential to worsen the course of psychotic disorders. It interferes with the willingness of many people to seek help, which results in a treatment delay, in turn leading to a more severe first manifestation of the illness. It can reduce life opportunities, limit social contacts, reduce self-esteem, and overall reduce quality of life. The central messages of many antistigma campaigns are often positively loaded with statements that mental illnesses are frequent, affect everyone, are treatable, and have a good prognosis if treated. They do not focus on the severe forms of psychosis that the public are often aware of and worried about. The question arises of whether the antistigma campaigns should also cater to psychotic disorders with poorer prognoses and severe disability. Such an approach would bring a more balanced view of mental disorders and an understanding of patients’ suffering. The International Classification of Functioning developed by WHO emphasizes the positive aspects of functioning of people with a health condition such as psychosis. It also turns the focus to the role of environmental factors (community, policies, disability-friendly services) that act as facilitators or barriers to patients’ efforts to live as contributing members of the mainstream society. This holistic approach would help the public understand and support people disabled by psychosis so they can attain an optimal level of functioning and improve the quality of their lives.

Inequity Of Health Care

There are critical gaps between those who need mental health services and those who receive the services and between optimally effective treatment for psychotic disorders and what many individuals receive in actual practice. Access is a serious problem for people with psychosis. In the U.S., less than 40% of people with severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia received any mental health treatment and a mere 15% received minimally adequate mental health services in a given year. Only 10% of people with bipolar disorder had a consultation with a mental health specialist. Nearly half of people with depression remain untreated. Even those who reach medical services are often not adequately treated in the primary care setting, and there is evidence to suggest that the outcome is worse if treated by the primary physician than when treated by a mental health professional. Given the high rates of morbidity and mortality associated with psychotic disorders, this state of affairs is a major public health concern.

One of the major barriers to narrowing the gap in care is fragmentation of care. This is especially problematic with an illness such as schizophrenia that necessitates a multisystemic interdisciplinary approach. Psychiatrists, nurses, vocational specialists, to name just a few, are integral members of a treatment team. Many services do not have such a team. Finding mental health specialists with the requisite skills and experience to treat psychotic disorders may be lacking, especially in rural areas.

If the gaps in services are as wide in developed countries as reported, it is bound to be worse in economically disadvantaged communities where the national budgetary expenditure on health is grossly inadequate to meet even the minimal needs of people with severe mental disorders. A large percentage of people with psychotic disorders living in developing countries remain untreated for life. Concerns about cost of care, lack of welfare support, medical insurance, cultural models of illness, unawareness, and stigma are among the foremost reasons why people do not seek or receive mental health care in developing countries.

Inequity in mental health care for people with psychotic disorders is influenced by economic status, gender, race, age, education, and geographic distance from services. Women, older persons, ethnic minorities, the economically disadvantaged, and rural populations more often fail to reach treatment and receive less than adequate services. High-prevalence preventable and communicable diseases with definite outcomes take precedence in receiving funding and other support. Parity between coverage for mental health and other health areas is an affordable and effective objective to seek.

Deinstitutionalization And Service Reforms

In the second part of the twentieth century, the development of mental health services in Western Europe was characterized by a dramatic conceptual and structural change: Deinstitutionalization. The focus of care shifted from inpatient care by closing down large and costly mental hospitals to outpatient community care of people with psychotic disorders and other severe mental illnesses. This resulted from several factors, including economic (cost-saving) and social factors (the right of people with severe mental disorders such as psychosis to live in the community). The emergence of effective psychotropic drugs in the 1950s, starting with chlorpromazine, was a further decisive factor contributing to the success of the deinstitutionalization programs.

The deinstitutionalization process led to the development of alternative community mental health services; integration of mental health with other health services; and generic, social, and community services such as accommodation and employment. There was a suspicion that deinstitutionalization might have gone too far. The increase in coercive activities such as compulsory psychiatric treatment, the number of suicides, the increasing number of forensic beds, acute admissions, and bed occupancy indicated a general trend toward reinstitutionalization. On the whole, the European experience made it obvious that a fundamental change in the principles and the organization of mental health care was possible across national borders. At the same time, differences in current mental health-care systems revealed that shared global developments do not necessarily result in comparable patterns of service provision. Reports on mental health-care reforms in several countries suggested that against the background of existing health-care structures as well as economic, social, political, and cultural characteristics, each country has to find its own way in order to accomplish the aims of deinstitutionalization and reintegration of the severely mentally ill into the community. A key task that lies ahead for both mental health service practitioners and researchers is to make sure that progress in mental health services is not lost within the increasing financial crisis of healthcare systems.

Consumer And Family Self-Help Movement

The public health importance of self-help groups is in influencing attitudes, health behavior, caring for others, and promoting policy discussion. The emergence of the self-help and support movement initiated by consumers and families has helped to shape the direction and complexion of mental health programs dealing with schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder. Although the origins and philosophy of these organizations differ, they have promoted common and important goals in patient care, protection of rights, and equity of service. Their participation in research and administrative committees has positively influenced the way research or treatment programs are implemented. The consumer and carer forums work toward reducing stigma and discrimination in policies and practices. They focus on recovery and social reintegration and draw attention to the special needs of people with psychotic disorders. The self-help movement has helped bring proper recognition of the individual and the legal rights of people with mental disorders, protecting them from exploitation and social degradation. In addition, families are no longer seen as causing disorders such as schizophrenia or as hindrances to treatment, but rather as valued participating members in the overall therapeutic environment. Organizations such as Rethink (formerly National Schizophrenia Fellowship), the National Alliance of the Mentally Ill (NAMI), Schizophrenics Anonymous, the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, and various websites provide information, support, and links to other services for consumers and their families.

Prevention Of Psychotic Disorders

Primary prevention of psychotic disorders with undetermined etiology has yet to evolve. Secondary and tertiary prevention of the disorders in the form of intervention during the early phases of the illness and reduction of relapses and deterioration, respectively, are possible. Several studies, particularly in Canada and Australia, have developed guidelines to detect psychotic disorders during the early phases in young people before the frank illness manifests. Although this has raised controversy in terms of labeling people with a mental disorder when they have no frank symptoms of psychosis, evidence has now accrued to show that a full attack of the disorder can be preempted by early intervention methods.

Relapse prevention and minimizing deterioration are the goals of tertiary prevention of psychotic disorders. Mental health education of patients and their caregivers to improve their understanding of the illness and the need for treatment, ensuring adherence to treatment recommendations, education on recognizing early signs of a relapse and proactive management of relapse, assertive follow-up and treatment in the community, minimizing hospitalization, and active multidisciplinary rehabilitation inputs are some of the measures geared toward successful tertiary prevention.

Reducing The Burden Of Psychotic Disorders

There are certain principles fundamental to the fulfillment of public health aims for people with psychotic disorders: identifying and providing appropriate help to those disabled by the disorders, gearing services to provide comprehensive and varied programs for short-term and long-term care, integrating services manned by professional and trained service providers, and globally reorienting public health policies and programs toward mental illness and in particular psychotic disorders. Care for patients with psychotic disorders could be improved by using common sense and readily available inexpensive, low-tech, evidence-based practices that reduce relapses and facilitate and maintain recovery. Since public health systems all over the world are invariably faced with resource constraints, establishing priorities, harvesting all resources available within the community rather than depending on public funding alone, and establishing some system of rationing is called for to produce maximum benefit to most people.

First and foremost, measures promoting the well-being of patients with psychotic disorders in the community are awareness, illness education, and reduction of stigma. This is necessary not only at the level of the individual and caregiver, but also at the level of the community. It is important to determine low treatment rates, even in people who have access to primary care medical services, evidence of the need for appropriate skills to identify and treat psychotic disorders in medical professionals in primary care. This can be addressed through training during undergraduate and postgraduate medical education and professional development programs aimed at practicing general practitioners and mental health professionals.

Efficient use of mental health professionals is required so that expert psychiatric care is provided to patients with psychosis. Such professionals are in chronic shortage all over the world, but the situation is worse in developing countries. The general practitioner plays a very crucial role in the pathway to recovery for people with psychotic disorders. While they may not be fully equipped to deal with the problem themselves, adequate support and a shared-care model with mental health professionals could help provide appropriate skilled care. Traditional healers are a common source of medical care in developing societies, especially in rural areas. It is recommended that an active liaison with the healers that includes educating them in identifying patients and referring them to appropriate medical care without prejudice to either system of medical practice be established. Such an approach respects the role of the traditional healer in the community while ensuring evidence-based care for people with psychotic disorders.

The public health burden of psychosis is lessened when the disorders are better treated at low cost, relapses are prevented, and patients live in the community and actively engage in life, fulfilling their family and social roles. Intervention programs that start with early detection and initiation of medical treatment that accompany on-going rehabilitation that focuses on bringing the patient back into mainstream community life are required. The programs need to be geared to the needs of the individual and have relevance to the community and culture. Such programs should provide support for people with psychosis for learning living skills, education, employment, accommodation, and economic independence. Disability support payments, while appropriate to the most disabled, can work as disincentives to engage in productive life and thus increase the burden on society. Public health services alone cannot cater to the diverse needs of people with psychotic disorders. Nongovernmental organizations are now playing an increasingly crucial role in long-term care. Encouraging the role of NGOs in mental health care is an optimal way of utilizing the community’s social capital.

The economic cost is probably the most crucial factor that determines the kind of political and policy decisions made that influence care provided for psychotic disorders. The amount of thought, effort, and resource allocation will be determined by how much will be gained by dealing with the problem as a public health issue. Decision makers need to be convinced that treatment of psychotic disorders would lead not only to better public health in general, but also contribute to the economy. There is now clear evidence that providing proper medical care and adequate support for community living cuts the cost of care, and patients brought back into mainstream and gainfully employed contribute to the economy. The increasing importance given to mental health in public health planning in some countries is based on this evidence. This change needs to be continued with the active participation of all stake holders.

Bibliography:

- Bleuler E (1911) Dementia Praecok oder Gruppe der Schizophrenia. Leipzig, Germany: Deuticke.

- Eronen M, Hakola P, and Tiihonen J (1996) Mental disorders and homicidal behavior in Finland. Archives of Geneneral Psychiatry 53: 497–501.

- Haslan J (1807) Observations on Madness and Melarcholy, 2nd edn. London: J. Callow.

- Kraepelin E (1896) Psychiatrie, 5th edn. Leipzing, Germany: Barth.

- Morel BA (1860) Traites des Maladies Mentales. Paris, France: Masson.

- Smit F, Cuijpers P, Oostenbrink J, Batelaan N, de Graaf R, and Beekman A (2006) Costs of nine common mental disorders: Implications for curative and preventive psychiatry. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 9(4): 193–200.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Andreasen NC and Black DW (2001) Introductory Textbook of Psychiatry, 3rd edn. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Becker T and Kilian R (2006) Psychiatric services for people with severe mental illness across Western Europe: What can be generalized from current knowledge about differences in provision, costs and outcomes of mental health care? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 113 (Supplement 429): 9–16.

- Gelder MG, Lopez-Ibor JJ Jr and Andreasen NC (eds.) (2000) New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Hales RE and Yudofsky SC (eds.) (2003) Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry, 4th edn. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Lieberman JA and Murray RM (eds.) (2001) Comprehensive Care of Schizophrenia, 1st edn. London: Martin Dunitz.

- Murray CJL and Lopez AD (1996) The Global Burden of Disease. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Neugebauer R (1999) Mind matters: The importance of mental disorders in public health’s 21st century mission. American Journal of Public Health 89: 1309–1311.

- Sadock BJ and Sadock VA (eds.) (2005) Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 8th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Satcher DS (2000) Executive summary: A report of the surgeon-general on mental health. Public Health Reports 115: 89–101.

- Stein DJ, Kupfer DJ, and Schatzberg AF (eds.) (2006) Textbook of Mood Disorders, 1st edn. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Thornicroft G and Tansella M (eds.) (1999) The Mental Health Matrix: A Manual to Improve Services. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- World Health Organization (1992) International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th Revision). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2001) The World Health Report 2001. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.