This sample Violence Against Women Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

Violence against women is a major public health problem and an abuse of women’s human rights. It is pervasive worldwide, although its prevalence varies between sites, as do the patterns and forms it takes. Violence against women is an important risk factor for women’s health, resulting in a wide range of negative outcomes for women’s health and well-being, including their sexual and reproductive health.

Violence against women can take many forms, including: physical, sexual, and emotional abuse by an intimate partner; rape and sexual assault whether by a partner, acquaintance, or stranger, or in the context of war; sexual abuse during childhood; trafficking for purposes of sex or forced labor; forced prostitution; female genital mutilation, child marriage, and other harmful traditional practices; and murders in the name of honor or related to dowry. Violence against women is also referred to as gender-based violence (GBV) because it is closely linked to gender inequality and to the social norms that perpetuate women’s and girls’ subordinate status in society.

This research papers focuses on intimate partner violence (also known as domestic violence), and sexual violence including during conflict and displacement, while also touching on child sexual abuse, trafficking of women and female genital mutilation, both because they are common forms of violence experienced by girls and women globally and because of their particular impact on sexual and reproductive health. While recognizing that the health consequences of violence are far-ranging and include, importantly, mental health, injuries, and other physical health problems, this research paper focuses on the sexual and reproductive health aspects.

How Widespread Is Violence Against Women?

A growing number of studies worldwide are documenting how common violence against women is. The majority of the population-based studies so far have focused on intimate partner violence, particularly physical and sexual (few studies so far also include emotional abuse), and less so on rape (by all perpetrators) and other forms of sexual abuse. Trafficking of women, violence during conflict and war, and other forms of violence against women remain understudied and not so well documented.

Intimate Partner Violence

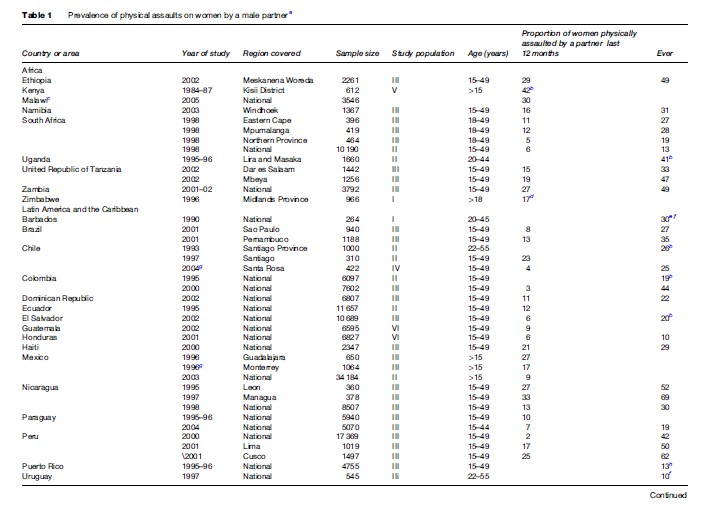

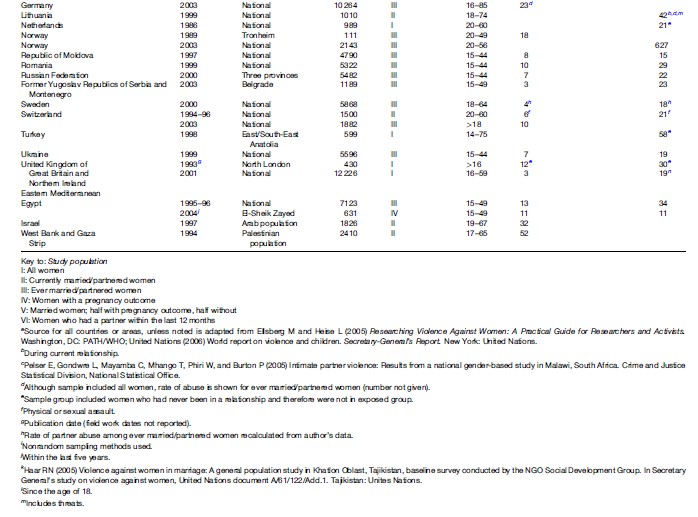

A review (to 1999) of population-based studies from around the world found that between 10 and 69% of women reported being physically abused by an intimate male partner at some point in their life (Heise and Garcia-Moreno, 2002). This violence is usually accompanied by sexual and emotional violence, and studies are beginning to collect data on these other forms of abuse. Table 1 summarizes existing data on the prevalence of partner physical violence.

Until recently, data on this problem, while valid, have been difficult to compare across countries due to methodological differences, for example, in sample size, measurement of violence, age, and characteristics of those interviewed.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Multi-Country Study on women’s health and domestic violence was designed to document the magnitude and nature of violence that women experienced, with a focus on intimate partner violence (its risk and protective factors, association with health outcomes, and women’s responses to such violence), with comparable methods across countries. Over 24 000 women were interviewed in 15 sites in 10 countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, Japan, Namibia, Peru, Samoa, Serbia, Thailand, and the United Republic of Tanzania (comparable data are now also available from Equatorial Guinea, the Maldives, and New Zealand). The study found that the lifetime prevalence of physical intimate partner violence was between 13 and 61%, with most sites reporting between 23 and 49%. The lifetime prevalence of intimate partner sexual violence was between 6 and 59%. Overall, between 15 and 71% of women reported physical or sexual violence, or both, in their lifetime (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006). Emotional abuse was also measured, asking about the presence and frequency of acts such as being insulted or made to feel bad, belittled, or humiliated in front of others, or threats to hurt someone you loved. Controlling behaviors were also measured and included: keeping a woman from seeing her friends, restricting contact with her family, insisting on knowing where she is at all times, expected to ask permission to seek health care, etc. Although there is less agreement about what constitutes emotional abuse, making it hard to determine its prevalence, women often report this as a most disempowering and devastating aspect of abuse by an intimate partner. Controlling behaviors by an intimate partner in the WHO study were found to be associated with perpetration of physical and sexual abuse. The study confirmed that there is wide variation in prevalence both between and within countries. The difference is particularly striking when looking at violence in the past year, with women in developing countries generally having a higher prevalence.

Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy

Partner violence often persists during pregnancy, with negative consequences for both maternal and infant health. Studies from the United States, Canada, and Europe have found a prevalence of violence during pregnancy to be between 3.4 and 11%. Studies from developing countries have found that 4 to 32% of women reporting have been subjected to physical violence (Campbell et al., 2004). In the WHO Multi-Country Study, the prevalence of physical abuse during pregnancy, among ever pregnant women, ranged from 4 to 12% in most sites. Abuse during pregnancy often involves blows to the abdomen, which may have serious consequences for both the mother and the infant as well. Overall, it would appear that this violence is a continuation of ongoing violence, with a small but varying percentage of women, depending on the site, reporting that this abuse started during the pregnancy. The evidence suggests that in some settings, pregnancy may offer protection, with violence decreasing during this time, while in others violence may increase (or start) as a result of pregnancy.

Sexual Violence, Including During Conflict And Displacement

Sexual violence is a global problem that until recently has remained hidden. It happens predominantly to women and girls, but boys and men are also sexually assaulted. The lifetime risk of attempted or completed rape is up to 20% for women ( Jewkes et al., 2002). Legal definitions may vary, but rape is usually defined as the nonconsensual penetration of the vagina, mouth, or anus, by a penis. When an object other than the penis is used, the term assault is usually employed.

There is increasing concern with the violence that women and children, primarily girls, experience during conflict and displacement. While exact estimates of the magnitude of such violence are difficult to determine, it has been documented in Bosnia, Colombia, Darfur in Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kosovo, and Rwanda, to name a few places (McGinn, 2001; Amnesty International, 2004). Abductions, sexual servitude, and violent rape by armed actors have also been reported. In situations of conflict and displacement, women may be exposed to rape and sexual abuse during the flight, on arrival and in camps, and after the conflict due to increased societal disruption and presence of weapons. Services are difficult to find in these situations, making things even more difficult, and women may be forced to trade sex for food or money.

Child Sexual Abuse And Forced First Sex

Women and girls are most at risk of sexual violence from people they know, whether partners or other family members, boyfriends, neighbors, acquaintances, and less frequently strangers. Precise estimates are difficult to give since sexual violence, particularly during childhood, remains a highly stigmatized and taboo subject in most societies. However, studies from around the world show that approximately 20% of women and 5 to 10% of men report having been sexually abused as children (WHO and ISPCAN, 2006). In the WHO Multi-Country Study the most commonly reported perpetrators of this were family members, particularly male family members other than fathers and stepfathers, although strangers were also an important category. Abuse during childhood has been found to be associated with abuse in later life (Fergusson et al., 1997; Coid et al., 2001). It is also associated with many unhealthy outcomes, particularly behavioral and psychological problems, low self-esteem and depression, and with high, sexual risk-taking behaviors, such as increased number of partners and increased use of alcohol and other substances.

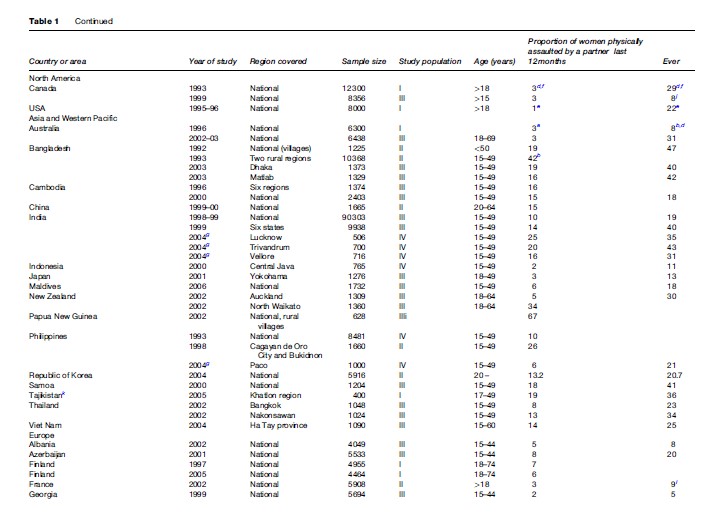

Forced sexual initiation is also a common occurrence. The WHO Multi-Country Study confirmed that a substantial proportion of young women reported their first experience of sexual intercourse as coerced or forced, which is consistent with studies from other countries, such as Uganda (Koenig et al., 2004) and Ghana (Glover et al., 2003). This was more likely to be the case the younger the reported age of the first sexual encounter (Figure 1). Coerced sex has been linked with lower use of modern contraception and of condom at last intercourse, more unwanted pregnancies, and more genital tract symptoms among young girls in Uganda (Koenig et al., 2004).

Trafficking Of Women

This form of violence is hard to document, particularly as it is an illegal practice, often carried out by bands of organized crime. Several organizations collect data on human trafficking, and while there is no agreement on what is the best estimate, there is agreement that it affects hundreds of thousands of people, particularly women and children, who are trafficked across borders in many parts of the world. Often this is for purposes of sex and prostitution, and these women are at increased risk of violence, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and mental health problems (Zimmerman, 2005).

Female Genital Mutilation

Other forms of violence against women include harmful practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM). FGM is a global concern (WHO, 2008). The WHO estimates that about 100–140 million women have been subjected to FGM in 28 countries in Africa as well as among immigrants in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Europe, and the United States. It appears that FGM is also practiced in some countries of Asia especially among certain populations in India, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The practice is being reported in the Middle East, particularly in northern Saudi Arabia, southern Jordan, Iraq, and Yemen. It has been estimated that approximately 3 million girls are mutilated each year (Yoder et al., 2004). The prevalence of FGM varies from country to country, and also varies between different ethnic groups within each country. For example, the prevalence is above 90% in Djibouti, Egypt, Guinea-Conakry, Mali, and Somalia, while the prevalence is only 5% in Niger and Uganda. The most severe form of FGM, Type III, involves excision of the labia minora and labia majora and suturing of the vaginal opening (with only a small opening left for urinating). Since FGM procedures are generally carried out under unhygienic conditions, they commonly result in shortand long-term complications and sequelae.

The Sexual And Reproductive Health Consequences Of Violence

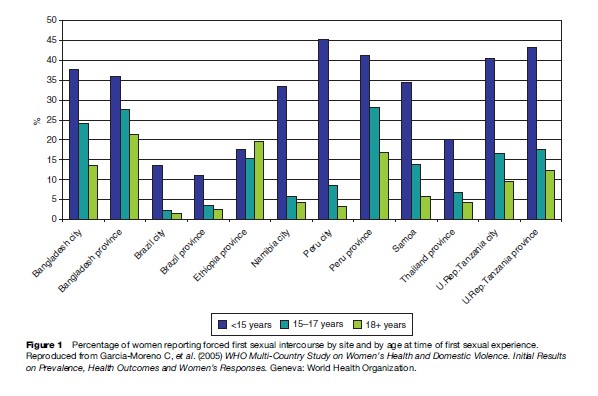

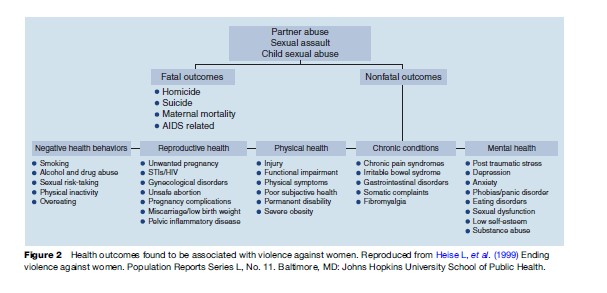

Violence against women is associated with a wide range of negative health outcomes (Resnick et al., 1997; Plichta and Falik, 2001; Campbell et al., 2002), including injuries, mental health problems, and adverse effects on sexual and reproductive health (Figure 2). The latter include: unwanted pregnancies and STIs, including HIV/AIDS, gynecological problems (Wijma et al., 2003), and abortion (Holmes et al., 1996). Vesico-vaginal and rectal fistulas can also result from violent rape, and this is particularly common in some conflict settings.

There are both direct and indirect pathways leading to sexual and reproductive ill health. Rape and sexual assault, for example, can directly result in unwanted pregnancy and STIs, including HIV. In addition, violence and fear of violence make it difficult to use contraception and to negotiate condom use and safe sex, thereby also leading to unwanted pregnancy and STIs. Sexual abuse during childhood has been associated with high-risk sexual behavior during adolescence and later in life, including an increased number of partners and early and unprotected sex, and use of alcohol and drugs – all factors that are associated with a higher risk of HIV infection.

Violence against women is associated with HIV and AIDS in a variety of ways. Violence by an intimate partner and fear of violence affect the opportunities for women to protect themselves and to request safer sex practices including condom use, and can also act as a barrier to HIV testing. Rape by an infected person can be responsible for HIV transmission or lead to other STIs and tears and lacerations, which increase the likelihood of HIV infection. Violence also interferes with women’s ability to access care and treatment. Lastly, violence can be an outcome of taking an HIV test and of disclosure of a positive serostatus (Maman et al., 2000; Dunkle et al., 2004).

Intimate partner abuse often persists during pregnancy (although, as stated previously, for some women this may be a protected time during which the violence is reduced). Abuse during pregnancy has been associated with premature delivery, second and third trimester bleeding, low birth weight, risk behaviors such as smoking and substance abuse during pregnancy, and late entry into prenatal care.

FGM, particularly the more severe form, is associated with recurrent urinary tract infections, dyspareunia (pain during sexual intercourse), and genital ulcers. A recent study in six African countries found that compared to women without FGM, women who had Type III genital mutilation were significantly more likely to experience cesarean section, postpartum hemorrhage, and prolonged hospitalization after delivery. Babies of women with FGM were more likely to require resuscitation and to be stillborn or suffer neonatal death (WHO Study Group on Female Genital Mutilation and Obstetric Outcome, 2006).

Responding To Violence Against Women

Preventing violence from occurring in the first place (i.e., primary prevention) is a public health priority, and the health sector can play an important role in gathering evidence and advocating for this. However, early childhood interventions, community-based and school-based, media, and other approaches to challenge social norms and promote behavior change among men, may be better suited for this (Figure 3).

Health-care services, particularly for sexual and reproductive health, have an important role to play in secondary and tertiary prevention by identifying women who are suffering intimate partner violence as early as possible and contributing to prevent its recurrence and mitigate its effects on women’s health (and lives) and that of their children. Most women come into contact with sexual and reproductive health services at some point in their lives, either for family planning, postabortion care, antenatal care, postpartum care, or treatment for STIs, and these contacts provide an opportunity for early identification and referral. These opportunities are, however, often lost because of health providers’ lack of training, lack of time, and fear of offending women, among other constraints. Wijma et al. (2003), for example, documented that despite the high prevalence of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse among women attending gynecological clinics in five Nordic countries, most victims of abuse were not identified by their gynecologists. This may mean that abused women do not get the care they need. Since violence affects both women’s health and the relevance and effectiveness of the care received, it is important that health-care providers understand and identify the problem as they may knowingly or unknowingly impair women’s ability to deal with this violence, offer inappropriate care, or put women at risk.

Health providers need to help women in abusive relationships to assess their risk and do a safety plan, and ensure that they have access to other services as needed. They also need to document the information in ways that can be used in court if a woman desires to pursue this option, while maintaining confidentiality and privacy. Similarly, with rape and sexual assault, there is a need to ensure that any provider can provide at least the initial management, including treatment of injuries, preservation of forensic evidence, prevention of unwanted pregnancies and STIs, referral for pregnancy termination where legal, and psychosocial support (WHO, 2003).

More needs to be done to educate physicians, nurses, midwives, and other primary health-care providers on gender equality and equity issues and on violence, whether this is a focus of their work or not. The most promising approaches in this regard are those that use a systems approach that goes beyond training individual providers. Profamilia, the family planning association in the Dominican Republic, provides an example of such an approach, in which attention to gender-based violence was systematically integrated throughout all of the organization’s services and at all levels (Population Council, 2006). Typically, these programs address all elements of care including both clinical and psychosocial support and establish partnerships with nongovernmental organizations or other service providers to ensure referral is possible. Others have attempted to provide all types of service in one location, usually in a hospital setting, as is the case with the One Stop Centers in Malaysia and other countries.

Programs need to be adapted to the specific context and the realities of health systems in different parts of the world. Everywhere, sexual and reproductive health-care providers must rise to the challenge of responding to women’s needs. Recognizing how common violence against women is and its impact on women’s health and lives is an important first step.

Conclusion

Violence against women is an important determinant of women’s sexual and reproductive health and a public health concern in all parts of the world. Health providers, particularly those who care for women, need to understand the nature of the problem, its dynamics and impact on women’s health and that of their families, and what they can do to mitigate its consequences and provide the care and support that women need.

Bibliography:

- Amnesty International (2004) Lives blown apart: Crimes against women in times of conflict: Stop violence against women. ACT 77/075/2004. http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGACT770752004 (accessed January 2008).

- Campbell J, Garcia-Moreno C, and Sharps P (2004) Abuse during pregnancy in industrialized and developing countries. Violence against Women 10: 770–789.

- Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, et al. (2002) Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine 162: 1157–1163.

- Coid A, Petruckevitch A, Feder G, et al. (2001) Relation between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimisation in women: A cross-sectional survey. The Lancet 358: 450–454.

- Dunkle K, Jewkes R, Brown HC, et al. (2004) Gender-based violence, relationship power and risk of HIV infection among women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. The Lancet 363: 1415–1421.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, and Lynskey MT (1997) Childhood sexual abuse, adolescent sexual behaviours and sexual revictimization. Child Abuse and Neglect 21: 789–803.

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HFAM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, and Watts C (2006) Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. The Lancet 368: 1260–1269.

- Glover EK, Bannerman A, Pence BW, et al. (2003) Sexual health experiences of adolescents in three Ghanaian towns. International Family Planning Perspectives 29: 32–40.

- Heise L, Ellsberg M, and Gottemuller M (1999) Ending violence against women. Population Reports Series L, No. 11.Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health.

- Heise L and Garcia-Moreno C (2002) Intimate partner violence. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, and Lozano R (eds.) World Report on Violence and Health, pp. 87–121. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Holmes MM, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, and Best CL (1996) Rape-related pregnancy: Estimates and descriptive characteristics from a national sample of women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 175: 320–324.

- Jewkes R, Sen P, and Garcia-Moreno C (2002) Sexual violence. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB and Lozano R (eds.) World Report on Violence and Health, pp. 149–181. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Koenig MA, Zablotska I, Lutalo T, et al. (2004) Coerced first intercourse and reproductive health among adolescent women in Rakai, Uganda. International Family Planning Perspectives 30: 156–163.

- Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat DC, and Gielen CA (2000) The intersections of HIV and violence: Directions for future research and interventions. Social Science and Medicine 50: 459–478.

- McGinn T (2001) Reproductive health of war-affected populations: What do we know? International Family Perspectives 26(4): 174–180.

- Plichta SB and Falik M (2001) Prevalence of violence and its implications for women’s health. Women’s Health Issues 11: 244–258.

- Population Council (2006) Living up to their name: Profamilia takes on gender-based violence (Quality/Calidad/Qualite). New York: Population Council.

- Resnick HS, Acierno R, and Kilpatrick DG (1997) Health impact of interpersonal violence. 2: Medical and mental health outcomes. Behavioural Medicine 23: 65–78.

- Wijma B, Schei B, Swahnberg K, et al. (2003) Emotional, physical and sexual abuse in patients visiting gynaecology clinics: A Nordic crosssectional study. The Lancet 361: 2107–2113.

- World Health Organization (2003) Guidelines for medico-legal care of victims of sexual violence. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- World Health Organization (2008) Interagency statement on the elimination of female genital mutilation. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. World Health Organization International Society for Prevention of Child

- Abuse Neglect (ISPCAN) (2006) Preventing child maltreatment: A guide to taking action and generating evidence. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO and ISPCAN.

- WHO Study Group on Female Genital Mutilation Obstetric Outcome (2006) Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. The Lancet 367: 1835–1841.

- Yoder PS, Abderrahim N, and Zhuzhuni A (2004) Female genital cutting in the Demographic and Health Surveys: A critical and comparative analysis. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro.

- Zimmerman C (2003) The Health Risks and Consequences of Trafficking in Women and Adolescents: Findings from a European Study. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- Ellsberg M (2005) Violence against women and the Millennium Development Goals: Facilitating women’s access to support. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 94: 325–332.

- Ellsberg M and Heise L (2005) Researching Violence against Women: A Practical Guide for Researchers and Activists. Washington, DC: PATH/WHO.

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, and Watts C (2005) WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence. Initial Results on Prevalence, Health Outcomes and Women’s Responses. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Guedes A (2004) Addressing gender-based violence from the reproductive health/HIV sector. A literature review and analysis.

- Washington, DC: The Population Technical Assistance Project (POPTECH Publication Number 04–164–020). http://www.igwg.org (accessed January 2008).

- Murphy CC, Schei B, Myhr TL, and Dumont J (2001) Abuse: A risk factor for low birth weight? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association 164: 1567–1572.

- Ramsay J, Rivas C, and Feder G (2005) Interventions to reduce violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience partner violence: A systematic review of controlled evaluations. Final Report. London: Barts and the London Queen Mary’s School of Dentistry.

- Spitz AM, Goodwin MM, Koenig L, et al. (2000) Special Issue: Violence and reproductive health. Maternal and Child Health Journal 4(2): 77–154.

- United Nations (2006) Ending Violence against Women. From Words to Action. Study of the Secretary-General. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations (2006) World report on violence and children. Secretary- General’s Report. New York: United Nations.

- World Health Organization (2005) Addressing violence against women and achieving the Millennium Development Goals. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- http://www.ippfwhr.org/programs/program_gbv_e.asp – International Planned Parenthood Federation, Western Hemisphere Region (IPPF/WHR).

- http://www.rhrc.org – Reproductive Health Response in Conflict Consortium.

- http://www.stoprapenow.org – Stop Rape Now, UN Action on Sexual Violence in Conflict.

- http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/vaw/SGstudyvaw – UN Division for the Advancement of Women, Violence against Women.

- http://www.who.int/gender – WHO Department of Gender, Women and Health (GWH).

- http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention – WHO Department of Violence and Injury Prevention and Disability (VIP).

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.