This sample Violence Prevention and Control Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of health research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Introduction

Globally violence kills more than 1.6 million people each year, and of these approximately 520 000 die from interpersonal violence, 870 000 from self-inflicted violence, and 170 000 from war (World Health Organization, 2002). Deaths are just the tip of the iceberg, and for every death there are numerous admissions to hospital and emergency departments. The clinical pyramid for all types of violence has not been properly estimated, but interpersonal violence is thought to result in at least 16 million injuries severe enough to warrant medical attention. The impact of nonfatal violence is thought to be enormous and has grave long-term physical, psychological, economic, and social consequences. This is particularly true of some forms of violence such as child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, and elder abuse, which are highly prevalent, and often nonfatal, but have far-reaching noninjury psychological and reproductive health consequences.

Interpersonal violence is thought to be one of the most frequently experienced yet commonly overlooked forms of violence and is a threat to health and communal security. Based upon data from victimization surveys, an estimated 170 million girls and 70 million boys are subjected to sexual abuse involving intercourse and other physical contact each year. The WHO multicountry study on domestic violence interviewed 24 000 women in urban and rural settings in ten countries, and showed that the proportion of women reporting having ever experienced sexual and/or physical violence at the hands of an intimate partner ranged from 15 to 71%. While some child maltreatment and intimate partner violence results in serious physical injuries, their major consequences are more insidious and far-reaching, with risk behaviors such as excessive smoking, eating disorders, and high-risk sexual behaviors, which in turn are associated with leading causes of death such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Whatever its form, interpersonal violence kills, maims, and otherwise destroys the health and well-being of tens of millions of people each year.

Although all types of interpersonal violence happen in all societies, their occurrence is far from random. Males aged 15–44 years are at many times greater risk of being involved – as victims and as perpetrators in both fatal and nonfatal violence. Females are at substantially higher risk than males of being victims of sexual violence and of serious physical assault in intimate partner violence. Homicide rates are strongly correlated with economic inequality, the highest rates occurring in the poorest communities of societies with the biggest gaps between the rich and the poor.

Worldwide, violence results in large expenditures not only for health care and social and economic development and support foregone, but also for other sectors, such as law enforcement, and compensating survivors for their suffering. It diverts many billions of dollars from more constructive investments. The fear of such violence provokes personal and societal reactions that further widen the gaps between the rich and the poor. There are enormous indirect costs, too, with large societal losses that can result in slower economic development, socioeconomic inequality, and an erosion of human and social capital (Waters et al., 2004). Those countries with the highest levels of interpersonal violence have experienced profound negative effects on their national economies by stunting economic development and eroding human and social capital. Ninety percent of deaths from violence are borne by lowand middle-income countries (LMICs), those least able to absorb the enormous socioeconomic and developmental impacts of violence.

This research paper highlights prevention strategies for interpersonal violence prevention, paying particular attention to child maltreatment and youth violence.

International Policy Priority

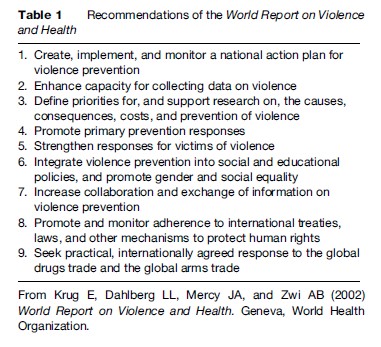

In 1996, the World Health Organization (WHO, 1996) highlighted the importance of violence as a public health threat in a World Health Assembly resolution WHA49.25 on the prevention of violence: A public health priority called upon national governments to give this area greater attention. This was followed in 2002 by the publication of the World Report on Violence and Health (Krug et al., 2002), which emphasized violence as a preventable public health problem and distilled the evidence base of actions required. Following this, the World Health Assembly resolution WHA56.24 on implementing the recommendations of the World Report on Violence and Health called on Member States to take such action (World Health Organization, 2003). These recommendations consist of six country level activities and three international-level activities (see Table 1), and form the backbone of the ongoing, WHO-led Global Campaign for Violence Prevention (World Health Organization, 2007c). Subsequently, WHO regional committees for Africa, the Americas, and Europe adopted resolutions calling on Member States to implement the recommendations of the World Report on Violence and Health.

The Millennium Declaration, adopted by the United Nations’ Member States in 2000, to reach the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by 2015 does not specifically mention violence. However, there is increasing concern that violence, in particular where it involves the use of firearms, destroys lives and livelihoods, breeds fear, and has a profoundly negative effect on human development, as stated by the Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development in 2006 (signed on 7 June 2006 by 42 countries) (World Health Organization, 2006). In addition, an emerging international consensus considers the prevention of violence necessary to the successful attainment of the MDGs (World Health Organization, 2007b). Violence will impede the attainment of all the MDGs. For example, a death or disability due to violence will lead to poverty, which will be most felt by the poorest, and violence will hinder national economic and local community development (MDG 1). Violence in the home will discourage attendance at schools by children (MDG 2), and, when targeting women, it can be used to maintain the status quo of gender inequality; this has been shown to be worse in the poorest (MDG 3). Women who have experienced violence in childhood may give birth prematurely, and violence during pregnancy may harm the fetus (MDG 4). Sexual violence may increase the risk of unintended pregnancy, a risk factor for maternal mortality (MDG 5), and increase the likelihood of HIV transmission (MDG 6). The growth of slums has led to unsafe environments with an increased risk of interpersonal violence (MDG 7), which exposes the poor to greater violence. In many countries, armed violence discourages and impedes the developmental efforts of aid agencies (MDG 8).

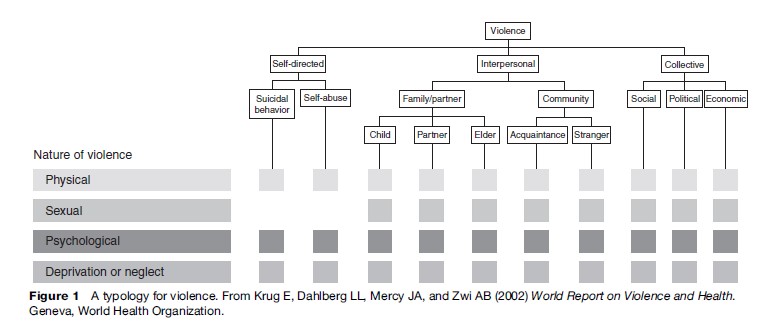

Defining Violence

The World Report on Violence and Health (Krug et al., 2002) defines violence as the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that results either in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation. Figure 1 shows the typology of violence, which can be divided into self-directed (as in suicide or self-harm), interpersonal (child, partner, elder, acquaintance, stranger), collective (in war and by gangs) and other intentional injuries (including deaths due to legal interventions). This research paper addresses interpersonal violence only. Many of the risk factors, however, are cross-cutting and there are synergies in the strategies for prevention, whether they address interpersonal, self-directed, or collective violence.

Interpersonal violence is violence between individuals or small groups of individuals. It is an insidious and frequently deadly social problem and includes child maltreatment, youth violence, intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and elder abuse. It takes place in the home, on the streets, and in other public settings, in the workplace and in institutions such as schools, hospitals, and residential care facilities (Figure 1).

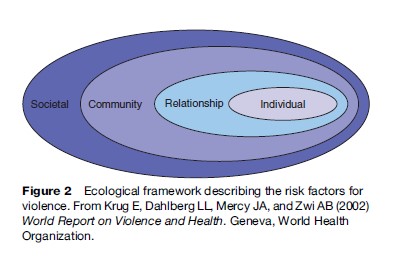

The Ecological Model For Violence Prevention And Risk Factors For Prevention

Violent incidents are often seen as an inevitable part of human life, events that are responded to, rather than prevented. The World Report on Violence and Health (Krug et al., 2002) challenged this notion and shows that violence can be predicted and is a preventable health problem. The report proposed an ecological model for understanding violence and its prevention, which classifies risk factors for violence by four levels: Individual, relationship, community, and societal (see Figure 2). Risk factors for violence are conditions that increase the possibility of becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence. No single factor explains why a person or group is at a high or low risk. Rather, violence is an outcome of a complex interaction among many factors. Although some risk factors may be unique to a particular type of violence, the various types of violence more commonly share a number of risk factors.

At the individual level, personal history and biological factors influence how individuals behave and their likelihood of becoming a victim or a perpetrator of violence. Among these factors are being a victim of child maltreatment, psychological or personality disorders, harmful alcohol use, substance abuse, a history of behaving aggressively or having experienced abuse, low educational achievement at school, and aggressive beliefs and attitudes. Perpetrators of child sexual abuse are more likely to be male; whereas the physical abuse of children is more often at the hands of females, males are more likely to inflict injuries that result in death.

Personal relationships such as those with family, friends, intimate partners, and peers may also influence the risks of becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence. For example, a poor relationship with a parent, being subjected to harsh physical punishment and humiliation, poor parental supervision, and having violent friends may influence whether a young person engages in or becomes a victim of violence. Child maltreatment is more likely to occur in households with a poor, young, single parent, those with low education, drug abuse, isolation, and unemployment; a prior history of abuse increases the risk of inflicting abuse.

Community contexts in which social relationships occur (such as schools, neighborhoods, and workplaces) also influence the likelihood of violence. Risk factors here may include the level of unemployment, population density and mobility, accessibility of alcohol, the existence of a local drug or gun trade, type and intensity of policing, poverty, a lack of social capital, and access to schooling and to adult supervision. Evidence from longitudinal and cohort studies shows that these community-level risk factors interact with individual and family-level factors to determine the risk of violence. These include being born of an unwanted pregnancy, experiencing parental abuse and neglect, coming from a dysfunctional family, and associating with violent and delinquent friends and peers.

Societal factors influence whether violence is encouraged or inhibited. These include economic and social policies that maintain socioeconomic inequalities between people, the availability of weapons, and social and cultural norms such as those relating to male dominance over females, parental dominance over children, and the endorsement of violence as an acceptable method to resolve conflicts. The depiction of violence in the media may have some role. Violence is also more prevalent in societies that have undergone armed violence or repression, and in those undergoing great social and economic turmoil. It is also higher in societies with large inequalities in wealth and lacking social protection policies. For child maltreatment, additional factors include child and family policies such as those relating to parental leave, schooling, social protection, and the responsiveness of the health and criminal justice systems. These can all affect the resources available and ability of parents to care for their children.

The ecological model is therefore useful in developing the preventive strategies that work to mitigate the risk factors and societal determinants of violence. Solutions for violence prevention need to be directed at multiple levels.

Life Course And Intergenerational Aspects Of Violence

There is strong evidence of the intergenerational continuation of child maltreatment. For example, mothers who had been severely physically abused as children were found to be at 13 times greater risk of having physically abused their own children when compared to those with supportive parents (Egeland, 1988). Mothers can break this cycle of violence, however, and continuity is not the rule; there are protective factors that need to be further researched. There is also a strong association between childhood sexual abuse and severe beatings by partners in adult life, with a 3.6 times increased risk of this occurring in comparison to women who were not abused as children. Women who were repeatedly abused as children had a much greater risk of revictimization in adult life (Coid, 2001). Childhood sexual abuse is a worldwide concern and, depending upon the case definition and the population studied, its prevalence varies from 2 to 62% in women and 3 to 16% in men. Studies indicate that the father is the most likely perpetrator in 22% of cases and other relatives in 19% of cases, with mothers as perpetrators in 4–8% of cases. Whereas the physical injuries may heal, the long-term psychological trauma can be severe (Johnson, 2004).

Filetti et al. (1998), in a cohort study of 26 000 California adults, found a high prevalence of adverse childhood experiences ranging from psychological abuse (11%), sexual abuse (22%), and physical abuse (11%), to living with a household member with substance misuse (26%), mental illness (19%), witnessing their mother treated violently (13%), and an imprisoned household member (3%). After 11 years of follow-up, a strong association was shown between the degree of exposure to adverse childhood experiences and adult health risk behaviors and diseases. People who had experienced four or more childhood exposures compared to those who had none, had 4–12 times greater risk of alcohol use disorders, substance abuse, depression, anxiety, sleep problems, and self-harm. There was also an increased likelihood of health-damaging behaviors such as smoking, multiple sexual partners, and physical inactivity, resulting in an increased incidence of adverse health outcomes such as sexually transmitted diseases, poor self-rated health, obesity, coronary heart disease, cancer, and respiratory illness. As the adverse childhood exposures increased, the risk of perpetrating abuse and of being in an abusive relationship, and the likelihood of being raped, increased. This ground-breaking study highlights the scale of adverse childhood experiences, the subsequent risk behaviors, perpetuation of the cycles of violence, and the consequences for ill health and health service use. Studies such as this and others indicate that the lifetime effects of child sexual abuse account for approximately 6% of cases of depression, 6% of harmful alcohol and/or drug misuse, 8% of suicide attempts, 10% of panic disorders, and 27% of posttraumatic stress disorders. These results have profound implications because they stress both the importance of primary prevention and the need for future research into risk and protective factors, screening for adverse childhood experiences, and tailoring services to match the needs of atrisk clients.

Public Health Approach To Violence Prevention

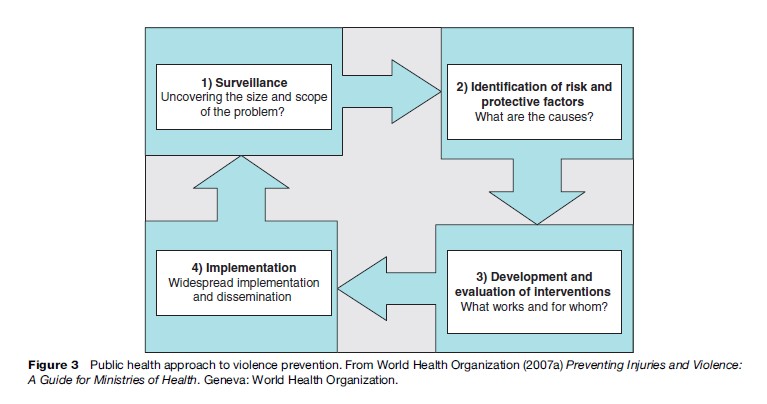

Figure 3 illustrates that the public health approach to preventing violence is a systematic approach, taking four logical steps. The first is surveillance, to find out the extent of the problem, where it occurs, and whom it affects. Second, risk factors are identified to understand why a certain group of people is at risk. Step three is to develop and evaluate interventions that work, and step four, the wide implementation of proven strategies, accompanied by evaluation. This approach can be used by stakeholders from different sectors and ensures that concrete measures are used to prevent violence.

Promoting Primary Prevention

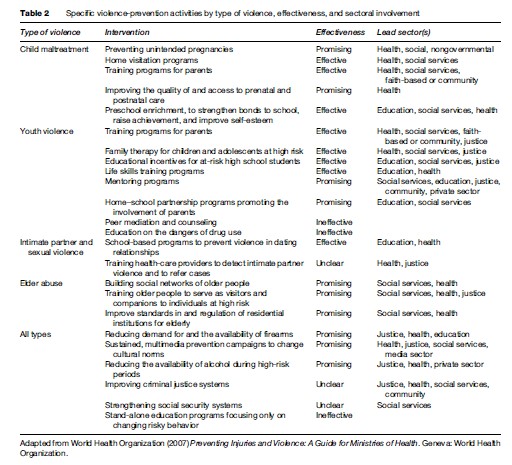

Many effective strategies have been documented to prevent violence at the individual level (interventions such as preschool enrichment or life-skills training programs, and incentives to complete secondary schooling), the relationship level (such as home visitation, parent training and mentoring), the community level (such as reducing alcohol availability and improving institutional policies in schools, workplaces, hospitals, and residential institutions) and at the societal level (public information campaigns, reducing access to means such as firearms, reducing inequalities, and strengthening police and judicial systems). These are summarized in Table 2 by type of violence, the effectiveness of the intervention, and the lead sectors that need to be engaged in delivering the service. In classifying the interventions according to level of effectiveness, the following definitions are used:

- Effective: Interventions evaluated with a strong research design, showing evidence of a preventive effect;

- Promising: Interventions evaluated with a strong research design, showing some evidence of a preventive effect but requiring more testing;

- Unclear: Interventions that have been poorly evaluated or that remain largely untested;

- Ineffective: Interventions evaluated with a strong research design, and consistently shown to have no preventive effect, or even to exacerbate the particular problem (the term ineffective is used only in relation to the impact on injury prevention).

Some of the areas for primary prevention are discussed in the following sections, starting with societal and community level interventions and ending with relationship and individual-level interventions.

Changing Cultural Norms That Support Violence

Cultural norms, such as those that glorify violence, diminish the status of children, and prescribe rigid gender roles, may increase the likelihood of violence. Changing cultural norms has been used effectively for other public health measures such as smoking and drunk-driving. There is growing evidence of effectiveness for violence prevention, in areas such as changing attitudes toward hitting and smacking children and female genital cutting. As in other areas of public health, information campaigns work best if accompanied by structural changes such as changes in legislation and services across the sectors, which reinforce messages with actions.

Promoting Gender And Social Equality

Gender inequality exists in most cultures to varying degrees and is thought to be causally associated with intimate partner violence. Cultural traditions that give preference to male traditions, early marriage for girls, female purity, and male sexual entitlement, place women in a subordinate position and make them vulnerable to violence. Ethnographic studies have shown that wife beating is most likely to occur where men hold the household economic and decision-making power, divorce is difficult to obtain, and violence is used to solve conflict. The Stepping Stones project from South Africa is an effective program that empowers women, discourages violence, and promotes communication; it has been shown to reduce both HIV transmission and intimate partner violence. Similarly, the Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity (IMAGE) Study succeeded in reducing intimate partner violence through the provision of microfinance to rural women; empowerment and educational information were provided at regular meetings. Pronyk et al. (2006) showed that rates of physical and sexual violence for the intervention group were halved. The profound implication of this study is that social and economic developments can alter risk environments for intimate partner violence. The inference for other types of violence may be equally far-reaching, but requires research to test this hypothesis.

Reducing Concentrations Of Poverty And Other Socioeconomic Factors

Social capital, social exclusion, the sense of cohesion that a community feels and the networks that exist in a society all influence individuals’ capacity to withstand social conflict without having to resort to violence. The explanation as to why poverty and socioeconomic factors influence the occurrence and outcomes of violence is complex. Wilkinson and Marmot have proposed that this is a combination of psychosocial factors, education, material resource, physical and social environments, the organization of work, high residential mobility, family disruption, and health behaviors. The recent trends in the rapid growth of urbanized populations in LMIC are a cause for concern. When community factors are controlled for, poverty per se has a weaker effect. What seems to matter more is income inequality, which is linked to homicide rates; societies with more even income distribution and structural safety nets seem to have lower homicide rates. Research evidence is limited, but that from the United States suggests that enabling housing schemes that allow people to move into better neighborhoods are associated with less adolescent violence and property crime.

Reducing The Availability And Misuse Of Alcohol And Drugs

Alcohol and drugs are strong precipitants to violent behavior and they are associated with being both a victim and perpetrator of violence. Much of the excess adult mortality in the world has been attributed to alcohol ingestion, with approximately 20–30% of all intentional injury deaths due to this cause (Lopez et al., 2006). Alcohol is implicated in up to 40% of violent attacks, though this may vary by setting. The introduction of free-market principles, the aggressive marketing strategies of alcohol manufacturers (particularly to youth), weak regulatory capacity, increasing social tolerance, illegal production, and smuggling of alcohol have led to increased consumption. The alcohol level in the blood is influenced by the type, volume, and pattern of drinking. Binge drinking of spirits is relatively common in youth in many countries and is strongly associated with violence. Countries such as some of the European countries in transition, which have low social capital and traditionally high levels of alcohol consumption, have seen large increases in alcohol abuse in those people who are the weakest in terms of social support and occupational status (Sethi et al., 2006). Experiencing or witnessing violence can lead to the harmful use of alcohol.

The creation of societal attitudes and environments that do not allow alcohol to be used as a pretext for violence and that discourage risky alcohol drinking is central to reducing violence at a societal level. Increasing alcohol prices through higher taxation is an effective way of reducing consumption and violence: Studies from the United States suggest that a 1% increase in the price of alcohol will decrease wife abuse by 5% and a 10% increase will reduce child abuse by 2%. Strictly enforcing pricing and licensing requirements and working with the entertainment industry and civic authorities are ways of reducing risky drinking and potentially violent situations, particularly in the urban nightlife environment.

Reducing Access To Firearms And Other Weapons

The availability of licensed or unlicensed firearms is a strong determinant of whether a violent episode will be fatal. For example, in Bogota and Cali, Colombia, city officials responded to high homicide rates at weekends by banning the carrying of handguns during these times; this resulted in a 15% decrease in homicides (Villaveces et al., 2000). For example, in 1993, 4352 homicides (roughly 80 per 100 000 population) occurred in Bogota, Colombia, a socially fragmented city where the homicide rate and living conditions were startlingly different between the rich and poor. Taking a lead from the recent experience in Cali, Antanas Mockus, mayor of Bogota (1995–96 and 2001–03) confronted the homicide challenge. His approach was to reverse the perception that violence was unavoidable and to tackle the social fragmentation between the rich and poor. Epidemiologists coordinated data collection from hospital emergency rooms, morgues, coroners’ offices, and the police to show clearly that homicides peaked on weekends and paydays. These were strongly associated with alcohol use and the availability of firearms. Petty arguments were prone to develop into fights that, owing to the availability of a firearm, ended fatally.

A multisectoral group advised on a prevention plan to reduce access to alcohol, the possession and carrying of firearms, and illicit drug use and trading. Unsafe physical environments such as unlit streets, poorly designed entertainment venues, and unsafe busy pedestrian routes were improved. Social inequalities were addressed by better access to schooling, public libraries in poor neighborhoods, job training, and employment opportunities for high-risk young people. The plan incorporated strategies for the prevention of unwanted pregnancies, home visits and parent training for high-risk parents-to-be and new parents, head-start programs for young children entering school, and life skills and social development training for children.

There was a decline in homicides on weekends, and, by successfully integrating the program into the long-term urban development strategy, Mr. Mockus ensured that it was sustained by subsequent mayors. At 3-year follow-up, homicide rates continued their downward trend and now the homicide rate is 18 per 100 000, the lowest rate in 20 years. Industry and businesses have now started to return and Bogota appears well on the road to rebuilding its social capital and reclaiming health security for its citizens.

Knives can also be lethal and the banning of their carriage can be effective.

Improving Services For Victims Of Violence

A comprehensive and equitable response needs to be developed for all victims of violence. Acute treatment of victims of violence by specialized emergency trauma services can lead to a reduction in fatality. This requires attention to treatment in both the prehospital and hospital phases. Physical and psychological rehabilitation may be required.

Health professionals need to be trained to recognize and treat types of violence that may be taboo, such as child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and elder abuse, as well as to provide long-term rehabilitation to prevent victims from resorting to violence. In view of the reproductive and mental health consequences of violence, often with the far-reaching consequences highlighted above, there is a need to provide the appropriate mental health and social services for victims. The impact of these services on breaking the cycle of violence needs to be evaluated. Victims of violence require services from the health, legal, forensic, and social sectors. An integrated and coordinated response would be beneficial to victims and would require training of workers. More research evidence is needed to evaluate the form and effectiveness of these services in breaking the cycle of violence.

Engaging The Health Sector In Violence Prevention

The health sector has been slow to engage in violence prevention, which is not perceived to be part of its traditional remit. However, health professionals are key players in providing services for victims, surveillance, evidence-based action, and evaluation, in acting as advocates and in providing preventive programs.

What Works To Prevent Child Maltreatment?

Rigorous scientific evaluations have clearly shown parent training and home visitation programs carried out by professionals to have a strong effect in reducing the abuse of children by parents. Therapeutic approaches to modifying behavior in violent parents have had some success. Training of police, teachers, and health professionals to recognize and manage abuse is also important. In this respect, the health sector has a critical role in the early detection of violence in children. Legislation to improve laws against violence in the home, including the physical punishment and humiliation of children at home, in school, and other settings, and the mandatory reporting of child abuse are examples of societal-level approaches (Krug et al., 2002).

What Works To Prevent Youth Violence?

Consistent with a life-course approach that identifies some of the key determinants of violence in infancy and early childhood exposures, youth violence prevention interventions with the strongest evidence for effectiveness are those targeted during infancy and early childhood to promote healthy brain development and prevent behavioral problems. However, effective and promising interventions have also been identified for work with adolescents and young adults. Preschool enrichment programs improve educational achievement and self-esteem and are associated with less violence in later life. Social development programs that are geared to reducing aggressive and antisocial behavior act to improve social skills with peers and promote cooperative behaviors, by managing anger, adopting a social perspective, resolving conflicts, and solving social problems (Butchart et al., 2004 World Health Organization, 2004). These are most effective if delivered in preschool or school and can be targeted to high-risk groups or be universal. Home visitation and training in parenting are examples of programs aimed at the relationship level. The former involves regular visits to the child’s home by a health professional and provides training, support, counseling, and monitoring for low-income mothers and for families at increased risk of abusing their children. The Triple-P Positive Parenting Programme combines a media campaign with consultations with primary care to improve parenting practices, the provision of intensive support to parents with children at risk of behavioral problems, and has been shown to be cost-effective in reducing violence (Saunders, 1999).

Promising community and societal-level programs include increasing the availability of child-care programs, preschool enrichment programs, creating safe routes to school, improving street lighting, providing extracurricular activities and after-school programs for children and adolescents such as sports to reduce involvement in underage drinking and antisocial behavior, improving school environments, and monitoring and removing toxins (such as lead) from the environment. Reducing the availability of alcohol and drugs is important. Providing incentives to complete high school is more cost-effective than incarceration. Changing the cultural and social environments by such means as deconcentrating poverty and reducing income inequality, altering night-time environments in city centers, reducing economic and social barriers to development, creating job programs, reducing access to firearms, and strengthening the criminal justice system are societal approaches that are intuitively and ethically appealing and require further evaluation.

Building The Foundations To Apply The Public Health Approach

The World Report on Violence and Health recommends concrete measures that are needed for country-level action. In all countries, but particularly in LMICs, it is important to build a foundation that supports the development, implementation, and monitoring of programs and policies. This requires building an infrastructure that is also common to other public health problems. The steps are briefly outlined below.

Developing A National Action Plan And Identifying A Lead Agency For Prevention

It is particularly important that the action plan engages stakeholders from the government and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and from all the concerned sectors, including health, justice, education, welfare, etc. It should be coordinated by an agency with the capacity to involve the actors in the multisectoral response. Plans should include reviewing and reforming legislation and policy, building data collection and research capacity, strengthening services for victims and implementing and monitoring prevention programs, with clear mandates for responsibility. One of the first steps is to document existing programs and policies for violence prevention.

Collecting Data For Action

Surveillance data are necessary to improve the understanding of the magnitude and causes of the problems in order to set priorities and guide the development and monitoring of prevention programs. This should consist of the collation of routine data from the health sector and other sectors, such as justice, on a number of key indicators that can be reliably measured with accuracy. The sharing of anonymized data from different sectors is key to building a complete picture and fostering ownership. For example, data from emergency departments capture many more cases of nonfatal violence than those from the police, capture the circumstances of victims’ injuries, and can be used to build a more complete picture of risk factors and to engage the police, civic authorities, and the leisure industry in directing interventions to violence hot spots, as shown in the United Kingdom. Routine questioning by health professionals with computerized data entry is an efficient way forward, as demonstrated in Jamaica. Standardized data need to be collected on not only the human costs of violence, but also the health and societal costs, to help improve the global picture.

Implementing And Evaluating Specific Actions To Prevent Violence

A number of effective and promising strategies can be adapted to local contexts and implemented. Greater priority needs to be given to primary prevention, particularly in children, to stop them becoming perpetrators of later violence. Interventions designed to prevent child abuse and youth violence are discussed in the sections above. Strategies that satisfy criteria for effectiveness, appropriateness, and sustainability need to be considered. Greater efficiency can be attained if these are integrated into existing schemes, such as parent training and support as part of regular maternal and child health checks (MacMillan, 2005). Rigorous evaluation of programs needs to be undertaken to build the knowledge base, especially in LMICs.

Integrating Violence Prevention Into Social Policy

Violence prevention policies need to be integrated and prioritized in the policies of the education and social sector and thereby reduce gender and social inequalities, which are risk factors for most types of violence. Social welfare systems that provide an economic safety net provide some protection from extreme poverty. Tackling inequalities requires political will to institute legal, educational, and social reforms. In LMICs, the integration of health, nutrition, education, social and economic development, and collaboration between government bodies and civil society lead to successful child development interventions. These multilevel interventions, with attention to cognitive development and better parenting skills, lead to better outcomes (Engle, 2007).

Sharing Knowledge And Information

Many national and international agencies work on violence prevention, but there is a need for greater collaborative work and information sharing. Valuable lessons could be shared between agencies, practitioners, and researchers, and may catalyze further action.

Conducting Research On Primary Prevention

There is a also a need to recognize the gaps in knowledge and to prioritize research and development, particularly in primary prevention at the societal and community level interventions. Most interventions have been developed in high-income settings, and there is a need to ensure more evaluative research takes place in LMICs. There is little information on the costs of violence and the cost-effectiveness of approaches. Such information is valuable for negotiating with policy makers.

Adherence To International Treaties

Adherence to international treaties and mechanisms for safeguarding human rights need to be improved. The illicit international trades in arms, drugs, alcohol, and people could be tackled with greater collaboration and attention to economic development in exporting countries.

Conclusion

This research paper has reiterated that interpersonal violence is a preventable public health problem. In using the ecological approach, the multiple risk factors and different levels at which preventive programs can be targeted has been emphasized. The intergenerational cycle of violence is one of the factors in the perpetuation of violence, and attention has been drawn to primary prevention efforts in early childhood to break the cycle of violence, and stop children from becoming perpetrators or victims as youth and adults. Good evidence already exists and has been presented; more research is needed, but there is enough knowledge to start convincing policy makers of the programs for prevention that make sound investments. This is the case for high-income countries, which are the main source of research evidence, and there is a need to engage policy makers and civil society in scaling up effective interventions in these settings. In contrast, in LMICs, which suffer 90% of the death toll from violence, there is a limited evidence base for what works for violence prevention, in spite of the scale of the human and economic burden, and the threat to future development in these countries. Thus, local research is needed on the underlying risk and protective factors, but more pressing is the need for outcome evaluation studies of effective preventive interventions that can be transferred from elsewhere. To do so requires investing resources to build capacity for implementing and evaluating these interventions in LMICs targeted to those areas, where the epidemiological data indicate that they would do the most good.

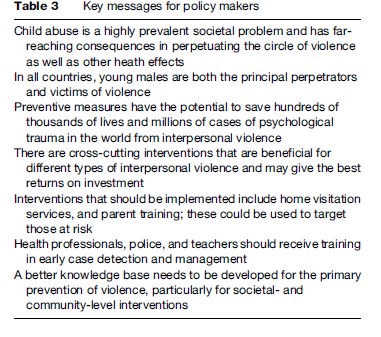

International policy initiatives such as the World Health Assembly resolution on violence prevention have been catalysts for policy action. For example, as of July 2007, 14 countries had drawn up action plans on violence and health; 18 had produced national reports on this topic, and over 100 health ministry officials had been appointed to coordinate violence-prevention activities. Such actions need to be scaled up and evaluated, and further resources need to be mobilized for this task. Table 3 summarizes some of the key messages to policy makers for the prevention of child maltreatment and youth violence.

Globalization (with the rapid cross-border movement of people, firearms, media messages, alcohol, and drugs) and the rapid pace of urbanization (with immense concentrations of poverty) poses both threats and opportunities. These threats can be counteracted by the flow of knowledge and skills of what works in the way of violence-prevention initiatives as a public health good. To ensure a wider implementation also requires an explicit recognition by policy makers and international development agencies that violence is a preventable public health problem. Resources need to be mobilized in order to build capacity and implement and evaluate interventions on a broader scale across all the sectors. Policies that safeguard children, youth, women, and elders from violence need to be integrated and prioritized across the broad range of social policy, whether this be education, health, social welfare, economic, and law enforcement policies. One of the challenges facing society is mobilizing the political support needed to tackle the current norms of violence, poverty, and alcohol consumption that perpetuate interpersonal violence in all its pervasive forms ( Jewkes, 2002). Much of the action so far has focused at the individual or at families; it is high time to also give attention to society and community-level interventions.

Bibliography:

- Butchart A, Harvey AP, Mian M, and Furniss T (2004) Preventing Child Maltreatment: A Guide to Taking Action and Generating Evidence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Feder G, Chung W, Richardson J, and Moorey S (2001) Relation between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimisation in women: A cross-sectional survey. Lancet 358: 450–454.

- Egeland B, Jacobvitz D, and Stroufe A (1988) Breaking the cycle of abuse. Child Development 59: 1080–1088.

- Engle PL, Black MM, Behrman JR, et al. (2007) Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world. Lancet 369: 229–242.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. (1998) American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14: 245–258.

- Jewkes R (2002) Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. Lancet 359: 1423–1429.

- Johnson CF (2004) Child sexual abuse. Lancet 364: 462–470.

- Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, and Zwi AB (2002) World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, and Murray CJL (eds.) (2006) Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. New York: World Bank.

- MacMillan HL, Thomas BH, Jamieson E, et al. (2005) Effectiveness of home visitation by public-health nurses in prevention of the recurrence of child physical abuse and neglect: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365: 1786–1793.

- Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Morison LA, et al. (2006) Effect of structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 368: 1973–1983.

- Saunders MR (1999) Triple-P-Positive Parenting Programme: Towards an empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavioural and emotional problems in children. Clinical, Child and Family Psychology Review 2: 71–90.

- Sethi D, Racciopi F, and Bertollini R (2006) Inequalities in injuries in Europe. Lancet 368: 2243–2250.

- Villaveces A, Cummings P, Espitia VE, Koepsell TD, McKnight B, and Kellermann AL (2000) Effect of a ban on carrying firearms on homicide rates in 2 Colombian cities. Journal of the American Medical Association 283: 1205–1209.

- Waters H, Hyder A, Rajkotia Y, Basu S, and Butchart A (2004) The Economic Dimensions of Interpersonal Violence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (1996) Prevention of Violence: A Public Health Priority. WHA49.25. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2002) Global burden of disease estimates. http://www3.who.int/whosis/menu.cfm?path=whosis,burden, burden_estimates,burden_estimates_2002N (accessed January 2008).

- World Health Organization (2003) World Health Assembly Resolution WHA56.24 on Implementing the Recommendations of the World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2004) Preventing Violence. A Guide to Implementing the Recommendations of the World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2006) The Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2007a) Preventing Injuries and Violence: A Guide for Ministries of Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2007b) Reducing the Impact of Violence on Health, Security and Growth: How Development Agencies Can Help? Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization and Violence Prevention Alliance.

- World Health Organization (2007c) 3rd Milestones in a Global Campaign for Violence Prevention Report 2007: Scaling up. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Ertem IO, Leventhal JM, and Dobbs S (2000) Intergenerational continuity of child physical abuse: How good is the evidence? Lancet 356: 814–819.

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsbeg M, Heise L, and Watts C (2005) WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence Against Women. Initial Responses on Prevalence, Health Outcomes and Women’s Responses. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Olds DL, Sadler L, and Kitzman H (2007) Programs for parents of infants and toddlers: Recent evidence from randomized trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 48: 355–391.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.